8.4 Personality at Work

Personality theories that utilize the trait approach have proven popular among investigators of employee behavior in organizations. There are several reasons for this. To begin with, trait theories focus largely on individuals in the average (working) adult population, in contrast to psychoanalytic and other personality theories that focus on clinical populations and behaviours. Trait theories identify several characteristics that describe people. In the study of people at work, we may discuss an employee’s dependability, emotional stability, or cognitive complexity. These traits, when taken together, form a large mosaic that provides insight into individuals. A third reason for the popularity of trait theories in the study of organizational behavior is that the traits that are identified are measurable and tend to remain relatively stable over time. It is much easier to make comparisons among employees using these tangible qualities rather than the somewhat mystical psychoanalytic theories or the highly abstract and volatile self theories.

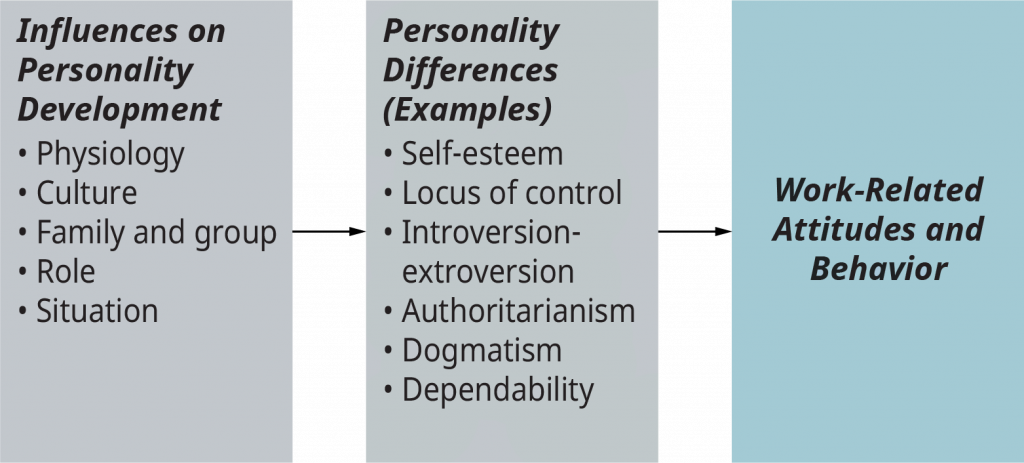

The number of traits people are believed to exhibit varies according to which theory we employ. In an exhaustive search, over 17,000 can be identified. We can identify six traits that seem to be relatively important for our purposes here, some of which relate to the constructs discussed in the previous section. It will be noted that some of these traits (for example, self-esteem or locus of control) have to do with how we see ourselves, whereas other traits (for example, introversion-extroversion or dependability) have to do with how we interact with others. Moreover, these traits are largely influenced by one’s personality development and, in turn, influence actual attitudes and behaviors at work, as shown in Figure 8.7 below.

Self-esteem

One trait that has emerged recently as a key variable in determining work behavior and effectiveness is an employee’s self-esteem. Self-esteem can be defined as one’s opinion or belief about one’s self and self-worth. It is how we see ourselves as individuals. Do we have confidence in ourselves? Do we think we are successful? Attractive? Worthy of others’ respect or friendship?

Research has shown that high self-esteem in school-age children enhances assertiveness, independence, and creativity. People with high self-esteem often find it easier to give and receive affection, set higher goals for personal achievement, and exert energy to try to attain goals set for them. Moreover, individuals with high self-esteem will be more likely to seek higher-status occupations and will take more risks in the job search. For example, one study found that students possessing higher self-esteem were more highly rated by college recruiters, received more job offers, and were more satisfied with their job search than students with low self-esteem (Ellis & Taylor, 1983). Hence, personality traits such as this one can affect your job and career even before you begin work!

People with high self-esteem view themselves in a positive light, are confident, and respect themselves. On the other hand, people with low self-esteem experience high levels of self-doubt and question their self-worth. High self-esteem is related to higher levels of satisfaction with one’s job and higher levels of performance on the job (Judge & Bono, 2001). People with low

self-esteem are attracted to situations in which they will be relatively invisible, such as large companies (Turban & Keon, 1993). Managing employees with low self-esteem may be challenging at times, because negative feedback given with the intention to improve performance may be viewed as a judgment on their worth as an employee. Therefore, effectively managing employees with relatively low self-esteem requires tact and providing lots of positive feedback when discussing performance incidents.

Locus of Control

Locus of control refers to the tendency among individuals to attribute the events affecting their lives either to their own actions or to external forces; it is a measure of how much you think you control your own destiny. Two types of individual are identified. People with an internal locus of control tend to attribute their successes—and failures—to their own abilities and efforts. Hence, a student would give herself credit for passing an examination; likewise, she would accept blame for failing.

In contrast, people with an external locus of control tend to attribute things that happen to them as being caused by someone or something else. They give themselves neither credit nor blame. Hence, passing an exam may be dismissed by saying it was “too easy,” whereas failing may be excused by convincing one’s self that the exam was “unfair.”

Recent research on locus of control suggests that people with an internal locus of control (1) exhibit greater work motivation, (2) have stronger expectations that effort will lead to actual high job performance, (3) perform better on tasks requiring learning or problem-solving, (4) typically receive higher salaries and salary increases, and (5) exhibit less job-related anxiety than externals (Nystrom, 1983; Spector, 1983). Locus of control has numerous implications for management. For example, consider what would happen if you placed an “internal” under tight supervision or an “external” under loose supervision. The results probably would not be very positive. Or what would happen if you placed both internals and externals on a merit-based compensation plan? Who would likely perform better? Who might perform better under a piece-rate system?

Internals thrive in contexts in which they have the ability to influence their own behaviour. Successful entrepreneurs tend to have high levels of internal locus of control (Certo & Certo, 2005). In addition, research has shown that individuals with an internal locus of control are more likely initiative to start mentor-protégé relationships. They are more involved with their jobs. They demonstrate higher levels of motivation and have more positive experiences at work (Ng et al., 2006; Reitz & Jewell, 1979; Turban & Dougherty, 1994). Interestingly, internal locus is also related to one’s subjective well-being and happiness in life, while being high in external locus is related to a higher rate of depression(Benassi et al., 1988; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998).

Introversion-Extroversion

The third personality dimension we should consider focuses on the extent to which people tend to be shy and retiring or socially gregarious. Introverts (introversion) tend to focus their energies inwardly and have a greater sensitivity to abstract feelings, whereas extroverts (extroversion) direct more of their attention to other people, objects, and events. Research evidence suggests that both types of people have a role to play in organizations (Morriss, 1979). Extroverts more often succeed in first-line management roles, where only superficial “people skills” are required; they also do better in field assignments—for example, as sales representatives. Introverts, on the other hand, tend to succeed in positions requiring more reflection, analysis, and sensitivity to people’s inner feelings and qualities. Such positions are included in a variety of departments within organizations, such as accounting, personnel, and computer operations. In view of the complex nature of modern organizations, both types of individual are clearly needed.

Authoritarianism and Dogmatism

Authoritarianism refers to an individual’s orientation toward authority. More specifically, an authoritarian orientation is generally characterized by an overriding conviction that it is right and proper for there to be clear status and power differences among people (Adorno et al., 1950). According to T. W. Adorno, a high authoritarian is typically (1) demanding, directive, and controlling of her subordinates; (2) submissive and deferential toward superiors; (3) intellectually rigid; (4) fearful of social change; (5) highly judgmental and categorical in reactions to others; (6) distrustful; and (7) hostile in response to restraint. Nonauthoritarians, on the other hand, generally believe that power and status differences should be minimized, that social change can be constructive, and that people should be more accepting and less judgmental of others.

In the workplace, the consequences of these differences can be tremendous. Research has shown, for example, that employees who are high in authoritarianism often perform better under rigid supervisory control, whereas those rated lower on this characteristic perform better under more participative supervision (Vroom, 1960). Can you think of other consequences that might result from these differences?

Related to this authoritarianism is the trait of dogmatism. Dogmatism refers to a particular cognitive style that is characterized by closed-mindedness and inflexibility (Rokeach, 1960). This dimension has particularly profound implications for managerial decision-making; it is found that dogmatic managers tend to make decisions quickly, based on only limited information and with a high degree of confidence in the correctness of their decisions (Taylor & Dunnette, 1974). Do you know managers (or professors) who tend to be dogmatic? How does this behavior affect those around them?

Dependability

Finally, people can be differentiated with respect to their behavioral consistency, or dependability. Individuals who are seen as self-reliant, responsible, consistent, and dependable are typically considered to be desirable colleagues or group members who will cooperate and work steadfastly toward group goals (Stogdill, 1948; Greer, 1955). Personnel managers often seek a wide array of information concerning dependability before hiring job applicants. Even so, contemporary managers often complain that many of today’s workers simply lack the feeling of personal responsibility necessary for efficient operations. Whether this is a result of the personal failings of the individuals or a lack of proper motivation by superiors remains to be determined.

The Interactionist Perspective: The Role of Fit

Individual differences matter in the workplace. Human beings bring in their personality, physical and mental abilities, and other stable traits to work. Imagine that you are interviewing an employee who is proactive, creative, and willing to take risks. Would this person be a good job candidate? What behaviours would you expect this person to demonstrate?

The question posed above is misleading. While human beings bring their traits to work, every organization is different, and every job within the organization is also different. According to the interactionist perspective, behaviour is a function of the person and the situation interacting with each other. Think about it. Would a shy person speak up in class? While a shy person may not feel like speaking, if the individual is very interested in the subject, knows the answers to the questions, and feels comfortable within the classroom environment, and if the instructor encourages participation and participation is 30% of the course grade, regardless of the level of shyness, the person may feel inclined to participate. Similarly, the behaviour you may expect from someone who is proactive, creative, and willing to take risks will depend on the situation.

When hiring employees, companies are interested in assessing at least two types of fit. Person–organization fit refers to the degree to which a person’s values, personality, goals, and other characteristics match those of the organization. Person–job fit is the degree to which a person’s skill, knowledge, abilities, and other characteristics match the job demands. Thus, someone who is proactive and creative may be a great fit for a company in the high-tech sector that would benefit from risk-taking individuals, but may be a poor fit for a company that rewards routine and predictable behaviour, such as accountants. Similarly, this person may be a great fit for a job such as a scientist, but a poor fit for a routine office job. The opening case illustrates one method of assessing person–organization and person–job fit in job applicants.

The first thing many recruiters look at is the person–job fit. This is not surprising, because person–job fit is related to a number of positive work attitudes such as satisfaction with the work environment, identification with the organization, job satisfaction, and work behaviours such as job performance. Companies are often also interested in hiring candidates who will fit into the company culture (those with high person–organization fit). When people fit into their organization, they tend to be more satisfied with their jobs, more committed to their companies, and more influential in their company, and they actually remain longer in their company (Anderson et al., 2008; Cable & DeRue, 2002; Caldwell & O’Reilly, 1990; Chatman, 1991; Judge & Cable, 1997; Kristof-Brown et al., 2005; O’Reilly et al., 1991; Saks & Ashforth, 2002).

One area of controversy is whether these people perform better. Some studies have found a positive relationship between person–organization fit and job performance, but this finding was not present in all studies, so it seems that fitting with a company’s culture will only sometimes predict job performance (Arthur et al., 2006). It also seems that fitting in with the company culture is more important to some people than to others. For example, people who have worked in multiple companies tend to understand the impact of a company’s culture better, and therefore they pay more attention to whether they will fit in with the company when making their decisions (Kristof-Brown et al., 2002). Also, when they build good relationships with their supervisors and the company, being a misfit does not seem to lead to dissatisfaction on the job (Erdogan et al., 2004)

Let’s Review

Let’s Review

While personality traits and other individual differences are important, we need to keep in mind that behaviour is jointly determined by the person and the situation. Certain situations bring out the best in people, and someone who is a poor performer in one job may turn into a star employee in a different job.

Case Study

Case Study

See Appendix A – Using Science to Match Candidates to Jobs: The Case of Kronos

Self-assessments

See Appendix B – Assessment: What is your locus of control?

Exercises

Exercises

- How can a company assess person–job fit before hiring employees? What are the methods you think would be helpful?

- How can a company determine person–organization fit before hiring employees? Which methods do you think would be helpful?

- What can organizations do to increase person–job and person–organization fit after they hire employees?

References

This section is adapted from:

Personality and Work Behaviour in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax, Rice University which is Rice University. and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Rice University. Except where otherwise noted.

Organizational Behaviour: Adapted for Seneca is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commerical 4.0 International license, except where otherwise noted.

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., & Levinson, D. J. (1950). The authoritarian personality. Harper & Row.

Anderson, C., Spataro, S. E., & Flynn, F. J. (2008). Personality and organizational culture as de terminants of influence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 702–710.

Arthur, W., Bell, S. T., Villado, A. J., & Doverspike, D. (2006). The use of person–organization fit in employment decision making: An assessment of its criterion-related validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 786–801.

Benassi, V. A., Sweeney, P. D., & Dufour, C. L. (1988). Is there a relation between locus of

control orientation and depression? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 357–367.

Cable, D. M., & DeRue, D. S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 875–884.

Caldwell, D. F., & O’Reilly, C. A. (1990). Measuring person–job fit with a profile comparison process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 648–657.

Certo, S. T., & Certo, S. C. (2005). Spotlight on entrepreneurship. Business Horizons, 48, 271–274.

Chatman, J. A. (1991). Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 459–484.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197–229.

Ellis, R. A. & Taylor, M. S. (1983). Role of self-esteem within the job search process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 632–640.

Erdogan, B., Kraimer, M. L., & Liden, R. C. (2004). Work value congruence and intrinsic career success. Personnel Psychology, 57, 305–332.

Greer, F. L. (1955). Small group effectiveness. Institute for Research on Human Relations.

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self esteem, generalized self efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 80–92.

Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (1997). Applicant personality, organizational culture, and organization attraction. Personnel Psychology, 50, 359–394.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Jansen, K. J., & Colbert, A. E. (2002). A policy-capturing study of the simultaneous effects of fit with jobs, groups, and organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 985–993.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342.

Morris, L. R. (1979). Extroversion and introversion: An interactional perspective. Hemisphere.

Ng, T. W. H., Soresen, K. L., & Eby, L. T. (2006). Locus of control at work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 1057–1087.

Nystrom, P. (1983). Managers’ salaries and their beliefs about reinforcement control. Journal of Social Psychology, 291–292.

O’Reilly, C. A., Chatman, J., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person–organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

Reitz, H. J., & Jewell, L. N. (1979). Sex, locus of control, and job involvement: A six-country investigation. Academy of Management Journal, 22, 72–80.

Rokeach, M. (1960). The open and closed mind. Basic Books.

Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (2002). Is job search related to employment quality? It all depends on the fit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 646–654.

Spector, P. (1982). Behavior in organizations as a function of locus of control,” Psychological Bulletin, 482–497

Stogdill, R. (1948). Personal factors associated with leadership: A survey of the literature. Journal of Psychology, 25, 35–71.

Taylor, R. N., & Dunnette, M. D. (1974). Influence of dogmatism, risk-taking propensity, and intelligence on decision-making strategies for a sample of industrial managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, 420–423.

Turban, D. B., & Dougherty, T. W. (1994). Role of protégé personality in receipt of mentoring and career success. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 688–702.

Turban, D. B., & Keon, T. L. (1993). Organizational attractiveness: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 184–193.

Vroom, V. H. (1960). Some personality determinants of the effects of participation. Prentice-Hall.