7.1 Understanding Decision-making

Individuals throughout organizations use the information they gather to make a wide range of decisions. These decisions may affect the lives of others and change the course of an organization. It is important to recognize that employees and managers alike are continually making decisions, and that the quality of their decision-making has an impact—sometimes quite significant—on the effectiveness of the organization and its stakeholders. Stakeholders are all the individuals or groups that are affected by an organization (such as customers, employees, shareholders, etc.).

Members of the top management team regularly make decisions that affect the future of the organization and all its stakeholders, such as deciding whether to pursue a new technology or product line. A good decision can enable the organization to thrive and survive long-term, while a poor decision can lead a business into bankruptcy. Managers at lower levels of the organization generally have a smaller impact on the organization’s survival, but can still have a tremendous impact on their department and its workers. Consider, for example, a first-line supervisor who is charged with scheduling workers and ordering raw materials for her department. Poor decision-making by lower-level managers is unlikely to drive the entire firm out of existence, but it can lead to many adverse outcomes such as:

- reduced productivity if there are too few workers or insufficient supplies,

- increased expenses if there are too many workers or too many supplies, particularly if the supplies have a limited shelf life or are costly to store, and

- frustration among employees, reduced morale, and increased turnover (which can be costly for the organization) if the decisions involve managing and training workers.

While it can be argued that management is decision making, half of the decisions made by managers within organizations ultimately fail (Ireland & Miller, 2004; Nutt, 2002; Nutt, 1999). Therefore, increasing effectiveness in decision making is an important part of maximizing your effectiveness at work. This chapter will help you understand how to make decisions alone or in a group while avoiding common decision-making pitfalls.

Types of Decisions

Because managers have limited time and must use that time wisely to be effective, it is important for them to distinguish between decisions that can have structure and routine applied to them (called programmed decisions) and decisions that are novel and require thought and attention (nonprogrammed decisions).

Programmed Decisions

Programmed decisions are those that are repeated over time and for which an existing set of rules can be developed to guide the process. These decisions might be simple, or they could be fairly complex, but the criteria that go into making the decision are all known or can at least be estimated with a reasonable degree of accuracy. For example, consider a retail store manager developing the weekly work schedule for part-time employees. The manager must consider how busy the store is likely to be, taking into account seasonal fluctuations in business. Then, they must consider the availability of the workers by taking into account requests for vacation and for other obligations that employees might have (such as school). Establishing the schedule might be complex, but it is still a programmed decision: it is made on a regular basis based on well-understood criteria, so structure can be applied to the process.

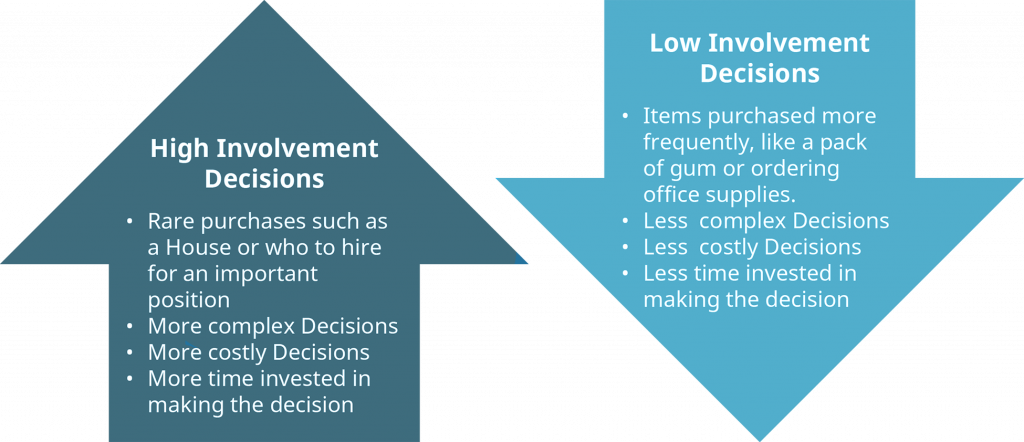

For programmed decisions, managers often develop heuristics, or mental shortcuts, to help reach a decision. For example, the retail store manager may not know how busy the store will be the week of a big sale, but might routinely increase staff by 30% every time there is a big sale (because this has been fairly effective in the past). Heuristics are efficient—they save time for the decision maker by generating an adequate solution quickly. Heuristics don’t necessarily yield the optimal solution—deeper cognitive processing may be required for that. However, they generally yield a good solution. Heuristics are often used for programmed decisions, because experience in making the decision over and over helps the decision maker know what to expect and how to react. Programmed decision-making can also be taught fairly easily to another person. The rules and criteria, and how they relate to outcomes, can be clearly laid out so that a good decision can be reached by the new decision maker. Programmed decisions are also sometimes referred to as routine or low-involvement decisions because they don’t require in-depth mental processing to reach a decision. High- and low-involvement decisions are illustrated in Figure 7.1

Nonprogrammed Decisions

In contrast, nonprogrammed decisions are novel, unstructured decisions that are generally based on criteria that are not well-defined. With nonprogrammed decisions, information is more likely to be ambiguous or incomplete, and the decision maker may need to exercise some thoughtful judgment and creative thinking to reach a good solution. These are also sometimes referred to as nonroutine decisions or as high-involvement decisions because they require greater involvement and thought on the part of the decision maker. For example, consider a manager trying to decide whether or not to adopt a new technology. There will always be unknowns in situations of this nature. Will the new technology really be better than the existing technology? Will it become widely accepted over time, or will some other technology become the standard? The best the manager can do in this situation is to gather as much relevant information as possible and make an educated guess as to whether the new technology will be worthwhile. Clearly, nonprogrammed decisions present the greater challenge.

Levels of Decision-making

Decisions can be classified into three categories based on the level at which they occur. Strategic decisions set the course of an organization. Tactical decisions are decisions about how things will get done. Finally, operational decisions refer to decisions that employees make each day to make the organization run. Oftentimes, these decisions follow the organizational hierarchy with CEOs and shareholders setting the tone via strategic mandates, managers deciding how the work should be done via tactical decisions, and employees making the day-to-day operational decisions that keep the organization running smoothly. These categories of decisions are depicted below in Table 7.1

Here’s an Example

Here’s an Example

Table 7.1 Examples of Decisions Commonly Made within Organizations

| Level of Decision | Examples of Decision | Who Typically Makes Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Decisions | Should we Merge with another company?

Should we pursue a new product line? Should we Downside our organization? |

Top management teams;, CEOs, and Boards of Directors |

| Technical Decisions | What should be do to help facilitate replies from the two companies working together?

How should we market the new product line? Who should we let go when we downsize? |

Managers |

| Operational Decisions | How often should I communicate with my new coworker?

What should I say to customers about our new product? Who will I balance my new work demands? |

Employees throughout the organization |

| Source (Converted from an image in original) | ||

Deciding When to Decide

While some decisions are simple, a manager’s decisions are often complex ones that involve a range of options and uncertain outcomes. When deciding among various options and uncertain outcomes, managers need to gather information, which leads them to another necessary decision: how much information is needed to make a good decision? Managers frequently make decisions without complete information; indeed, one of the hallmarks of an effective leader is the ability to determine when to hold off on a decision and gather more information, and when to make a decision with the information at hand. Waiting too long to make a decision can be as harmful for the organization as reaching a decision too quickly. Failing to react quickly enough can lead to missed opportunities, yet acting too quickly can lead to organizational resources being poorly allocated to projects with no chance of success. Effective managers must decide when they have gathered enough information and must be prepared to change course if additional information becomes available that makes it clear that the original decision was a poor one. For individuals with fragile egos, changing course can be challenging because admitting to a mistake can be harder than forging ahead with a bad plan. Effective managers recognize that given the complexity of many tasks, some failures are inevitable. They also realize that it’s better to minimize a bad decision’s impact on the organization and its stakeholders by recognizing it quickly and correcting it.

What’s the Right (Correct) Answer?

It’s also worth noting that making decisions as a manager is not at all like taking a multiple-choice test: with a multiple-choice test there is always one right answer. This is rarely the case with management decisions. Sometimes a manager is choosing between multiple good options, and it’s not clear which will be the best. Other times there are multiple bad options, and the task is to minimize harm. Often there are individuals in the organization with competing interests, and the manager must make decisions knowing that someone will be upset no matter what decision is reached.

What’s the Right (Ethical) Answer?

Sometimes managers are asked to make decisions that go beyond just upsetting someone—they may be asked to make decisions in which harm could be caused to others. These decisions have ethical or moral implications. Ethics and morals refer to our beliefs about what is right vs. wrong, good vs. evil, virtuous vs. corrupt. Implicitly, ethics and morals relate to our interactions with and impact on others—if we never had to interact with another creature, we would not have to think about how our behaviors affected other individuals or groups. All managers, however, make decisions that impact others. It is therefore important to be mindful about whether our decisions have a positive or a negative impact. “Maximizing shareholder wealth” is often used as a rationalization for placing the importance of short-term profits over the needs of others who will be affected by a decision—such as employees, customers, or local citizens (who might be affected, for example, by environmental decisions). Maximizing shareholder wealth is often a short-sighted decision, however, because it can harm the organization’s financial viability in the future (Stout, 2012). Bad publicity, customers boycotting the organization, and government fines are all possible long-term outcomes when managers make choices that cause harm in order to maximize shareholder wealth. More importantly, increasing the wealth of shareholders is not an acceptable reason for causing harm to others. We will talk more about ethics in a future chapter.

Decision-making Systems in the Human Brain

The human brain processes information for decision-making using one of two routes: a reflective system and a reactive (or reflexive) system (Facione & Facione, 2007; Lieberman, 2003). The reflective system is logical, analytical, deliberate, and methodical, while the reactive system is quick, impulsive, and intuitive, relying on emotions or habits to provide cues for what to do next. Research in neuropsychology suggests that the brain can only use one system at a time for processing information (Darlow & Sloman, 2010) and that the two systems are directed by different parts of the brain. The prefrontal cortex is more involved in the reflective system, and the basal ganglia and amygdala (more primitive parts of the brain, from an evolutionary perspective) are more involved in the reactive system (Darlow & Sloman, 2010).

Reactive Decision-Making

We tend to assume that the logical, analytical route leads to superior decisions, but whether this is accurate depends on the situation. The quick, intuitive route can be lifesaving; when we suddenly feel intense fear, a fight-or-flight response kicks in that leads to immediate action without methodically weighing all possible options and their consequences. Additionally, experienced managers can often make decisions very quickly because experience or expertise has taught them what to do in a given situation. These managers might not be able to explain the logic behind their decision, and will instead say they just went with their “gut,” or did what “felt” right. Because the manager has faced a similar situation in the past and has figured out how to deal with it, the brain shifts immediately to the quick, intuitive decision-making system (Gladwell, 2005).

Reflective Decision-Making

The quick route is not always the best decision-making path to take, however. When faced with novel and complex situations, it is better to process available information logically, analytically, and methodically. As a manager, you need to think about whether a situation requires not a fast, “gut” reaction, but some serious thought prior to making a decision. It is especially important to pay attention to your emotions, because strong emotions can make it difficult to process information rationally. Successful managers recognize the effects of emotions and know to wait and address a volatile situation after their emotions have calmed down. Intense emotions—whether positive or negative—tend to pull us toward the quick, reactive route of decision-making. Have you ever made a large “impulse” purchase that you were excited about, only to regret it later? This speaks to the power our emotions exert on our decision-making. Big decisions should generally not be made impulsively, but reflectively.

The Role of Emotions

Being aware of the role emotions play in decision-making does not mean that we should ignore them. Emotions can serve as powerful signals about what we should do, especially in situations with ethical implications. Thinking through how we feel about the possible options, and why we feel that way, can greatly enhance our decision-making (George, 2000). Effective decision-making, then, relies on both logic and emotions. For this reason, the concept of emotional intelligence has become popular as a characteristic of effective managers.

Recall, emotional intelligence is the ability to recognize, understand, pay attention to, and manage one’s own emotions and the emotions of others. It involves self-awareness and self-regulation—essentially, this is a toggling back and forth between emotions and logic so that we analyze and understand our own emotions and then exert the necessary control to manage them as appropriate for the situation. Emotional intelligence also involves empathy—the ability to understand other peoples’ emotions (and an interest in doing so). Finally, emotional intelligence involves social skills to manage the emotional aspects of relationships with others. Managers who are aware of their own emotions can think through what their emotions mean in a given situation and use that information to guide their decision-making. Managers who are aware of the emotions of others can also utilize that information to help groups function more effectively and engage in better group decision-making. While emotional intelligence seems to come easily to some people, it is something that we can develop and improve on with practice.

Let’s Reflect

Sometimes when we are faced with making a hard decision, we can be overly emotional and therefore make the wrong one. By developing self-awareness skills (I am feeling xx way) and then managing our emotions once we recognize them, we can learn to make healthy, wise decisions. As you read later in this chapter about the Debono decision-making model, this model specifically asks that you look at your own emotions and the emotions of others. This is part of self-awareness and social awareness in emotional intelligence. Without these skills, it can be difficult to make good decisions.

Sometimes when we are faced with making a hard decision, we can be overly emotional and therefore make the wrong one. By developing self-awareness skills (I am feeling xx way) and then managing our emotions once we recognize them, we can learn to make healthy, wise decisions. As you read later in this chapter about the Debono decision-making model, this model specifically asks that you look at your own emotions and the emotions of others. This is part of self-awareness and social awareness in emotional intelligence. Without these skills, it can be difficult to make good decisions.

The ability to make good decisions can help us become happier people, thus better at communicating and maintaining our interpersonal relationships in our work and personal lives. When we understand how we feel about a certain decision we have to make, we can look realistically at all possible solutions from a cognitive level, which allows us to also make better decisions. These emotional intelligence skills, specifically self-awareness and self-management, can help us make thoughtful, sound decisions that improve our productivity, happiness, and satisfaction.

Let’s Review

Let’s Review

- Decision making is choosing among alternative courses of action.

- At various levels in an organization employees and managers make decisions. Strategic decisions offer big picture ideas, tactical decisions offer solutions to how to accomplish these goals, and operational decisions are the day-to-day decisions made by employees.

- There are different types of decisions ranging from automatic, programmed decisions to more intensive nonprogrammed decisions.

- Our brain’s reactive system makes quick and intuitive decisions. The reflective system is slower, more deliberate and logical.

- Our emotions impact our ability to make good decisions. Developing our emotional intelligence skills can help us to understand our emotions and also consider other points of view. Ultimately, this can lead to better decision-making in the workplace.

Exercises

Exercises

- What do you see as the main difference between a successful and an unsuccessful decision? How much does luck versus skill have to do with it? How much time needs to pass to know if a decision is successful or not?

- Research has shown that over half of the decisions made within organizations fail. Does this surprise you? Why or why not?

- Provide an example of a time that you used a decision rule and a time that you made a nonprogrammed decision.

- How can recognizing strong emotions help you to make better decisions at work?

References

This section is adapted from:

Make Good Decisions in Human Relations by Saylor Academy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License

6.1 Overview of Managerial Decision-making and 6.2 How the Brain Processes Information to Make Decisions: Reflexive and Reactive Systems, and 6.3 Programmed and Non-programmed Decisions in Organizational Behaviour by Rice University, OpenStax under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Darlow, A. L. & Sloman, S. A. (2010). Two systems of reasoning: Architecture and relation to emotion, WIREs Cognitive Science, 1, 382-392.

Facione, P. A. & Facione, N. C. (2007). Thinking and reasoning in human decision making: The method of argument and heuristic analysis. The California Academic Press.

George, J. M. (2000). Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence. Human Relations, 53, 1027-1055.

Gladwell, M. (2005). Blink: The power of thinking without thinking. Back Bay Books.

Ireland, R. D., & Miller, C. C. (2004). Decision making and firm success. Academy of Management Executive, 18, 8–12.

Lieberman, M. D. (2003). Reflexive and reflective judgment processes: A social cognitive neuroscience approach. In (Eds.) Joseph P. Forgas, Kipling D. Williams, & William von Hippel’s. Social judgments: Implicit and explicit processes (pp. 44-67). Cambridge University Press.

Nutt, P. C. (1999). Surprising but true: Half the decisions in organizations fail. Academy of Management Executive, 13, 75–90.

Nutt, P. C. (2002). Why decisions fail. Berrett-Koehler.

Stout, L. (2012). The shareholder value myth: How putting shareholders first harms investors, corporations, and the public. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.