2.4 Negotiation

In this section:

Negotiation Defined

Where two people come in contact with one another, there is a potential for conflict. In this way, conflict can result in the need for negotiation. Alternatively, the need for negotiation can arise out of two parties’ willingness to exchange goods and services.

All negotiations share four common characteristics:

- The parties involved are somehow interdependent

- The parties are each looking to achieve the best possible result in the interaction for themselves

- The parties are motivated and capable of influencing one another

- The parties believe they can reach an agreement

If these conditions don’t exist, neither can a negotiation. The parties have to be interdependent—whether they are experiencing a conflict at work or want to do business with one another. Each has an interest in achieving the best possible result. The parties are motivated and capable of influencing one another, like a union bargaining for better working conditions. A worker doesn’t have influence over a manufacturer, but a union of workers does, and without that influence as a factor, both parties won’t be motivated to come to the table for discussions. Finally, the parties need to believe they can reach an agreement; otherwise any negotiation talks will be futile.

Let’s Practice

Approaches to Bargaining

In a negotiation, parties must select an approach to that they believe will assist them in the attainment of their objectives. In general, two rather distinct approaches to negotiation can be identified. These are distributive bargaining and integrative bargaining. Let’s compare these strategies.

Distributive Bargaining

In essence, distributive bargaining is “win-lose” or fixed-pie bargaining. That is, the goals of one party are in fundamental and direct conflict with those of the other party. Negotiators see the situation as a pie that they have to divide between them. Each tries to get more of the pie and “win.” Resources are fixed and limited, and each party wants to maximize their share of these resources. Finally, in most cases, this situation represents a short-term relationship between the two parties. In fact, such parties may not see each other ever again.

For example, managers may compete over shares of a budget. If marketing gets a 10% increase in its budget, another department such as the research and development department will need to decrease its budget by 10% to offset the marketing increase. Focusing on a fixed pie is a common mistake in negotiation, because this view limits the creative solutions possible. Another example of this can be seen in the relationship between the buyer and seller of an item. If the buyer gets the item for less money (that is, they “win”), the seller also gets less (that is, they “lose”).

Under such circumstances, each side will probably adopt a course of action as follows. First, each side to a dispute will attempt to discover just how far the other side is willing to go to reach an accord. This can be done by offering outrageously low (or high) proposals simply to feel out the opponent. For example, in selling an item, the seller will typically ask a higher price than she actually hopes to get. The buyer, in turn, typically offers far less than she is willing to pay. These two prices are put forth to discover the opponent’s resistance price. The resistance price is the point beyond which the opponent will not go to reach a settlement. Once the resistance point has been estimated, each party tries to convince the opponent that the offer on the table is the best one the opponent is likely to receive and that the opponent should accept it. As both sides engage in similar tactics, the winner is often determined by who has the best strategic and political skills to convince the other party that this is the best she can get.

Integrative Bargaining

A newer, more creative approach to negotiation is called the integrated approach. In this approach, both parties look for ways to integrate their goals. That is, they look for ways to expand the pie, so that each party gets more. This is also called a win–win approach. The first step of the integrative approach is to enter the negotiation from a cooperative rather than an adversarial stance. The second step is all about listening. Listening develops trust as each party learns what the other wants and everyone involved arrives at a mutual understanding. Then, all parties can explore ways to achieve the individual goals. The general idea is, “If we put our heads together, we can find a solution that addresses everybody’s needs.” Unfortunately, integrative outcomes are not the norm. A summary of 32 experiments on negotiations found that although they could have resulted in integrated outcomes, only 20% did so (Thompson & Hrebec, 1996). One key factor related to finding integrated solutions is the experience of the negotiators who were able to reach them (Thompson, 1990).

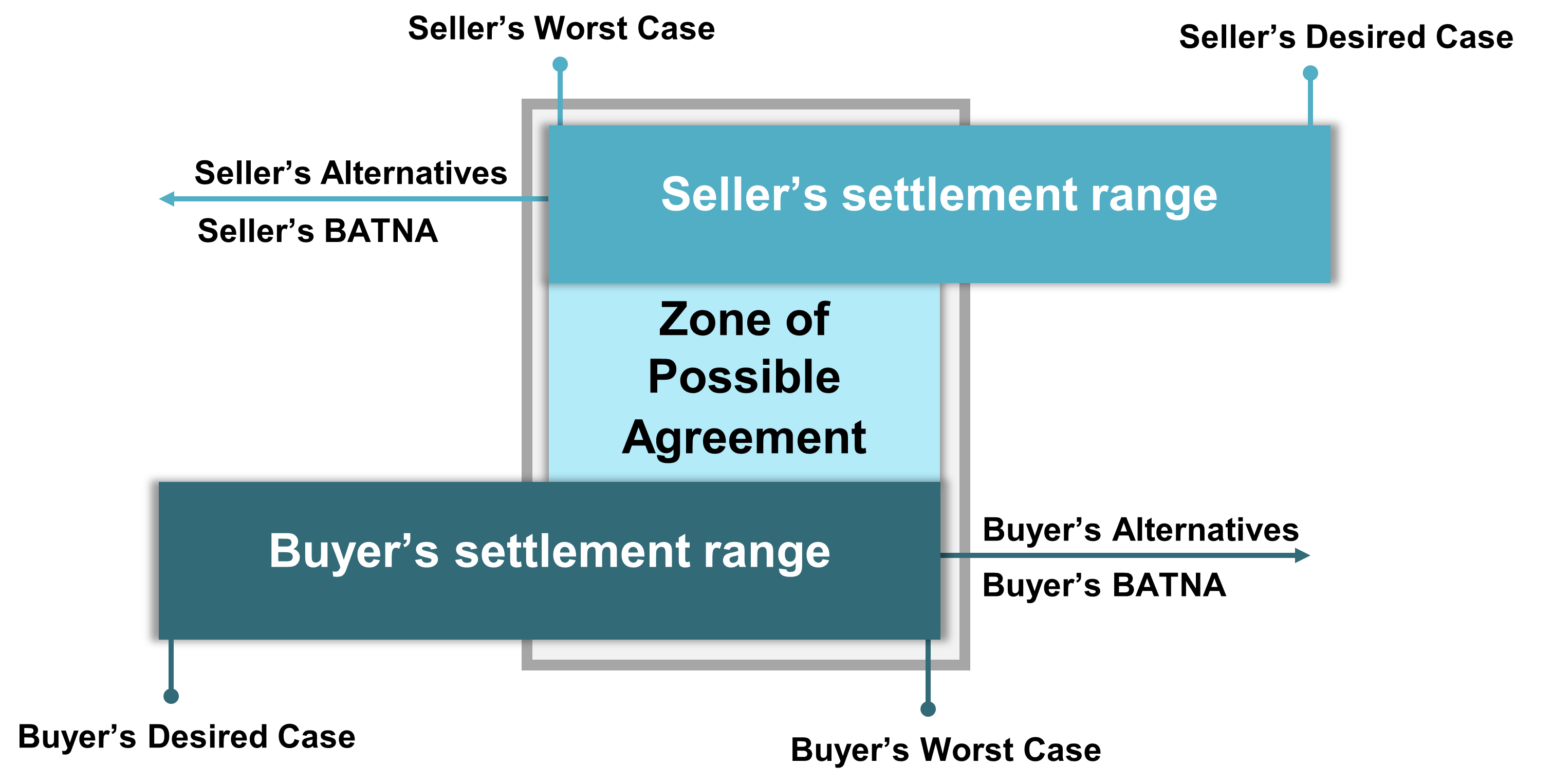

One of the classic negotiations approaches consistent with the integrated approach is the book Getting to Yes (Fisher & Ury, 1981; Fisher et al., 2012). This book expound the authors favored method of conflict resolution, which they term principled negotiation. This method attempts to find an objective standard, typically based on existing precedents, for reaching an agreement that will be acceptable to both interested parties. Principled negotiation emphasizes the parties’ enduring interests, objectively existing resources, and available alternatives, rather than transient positions that the parties may choose to take during the negotiation. The outcome of a principled negotiation ultimately depends on the relative attractiveness of each party’s so-called BATNA: the “Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement”, which can be taken as a measure of the objective strength of a party’s bargaining stance. In general, the party with the more attractive BATNA gets the better of the deal. If both parties have attractive BATNAs, the best course of action may be not to reach an agreement at all (Fisher & Ury, 1981; Fisher et al., 2012; Edwards, 2013).

This integrated approach is characterized by the existence of variable resources to be divided, efforts to maximize joint outcomes, and the desire to establish or maintain a long-term relationship. The interests of the two parties may be convergent (noncompetitive, such as preventing a trade war between two countries) or congruent (mutually supportive, as when two countries reach a mutual defense pact).

Bargaining tactics are quite different from those typically found in distributive bargaining. Here, both sides must be able and willing to understand the viewpoints of the other party. Otherwise, they will not know where possible consensus lies. Moreover, the free flow of information is required. Obviously, some degree of trust is required here too. In discussions, emphasis is placed on identifying commonalities between the two parties; the differences are played down. And, finally, the search for a solution focuses on selecting those courses of action that meet the goals and objectives of both sides. This approach requires considerably more time and energy than distributive bargaining, yet, under certain circumstances, it has the potential to lead to far more creative and long-lasting solutions.

Table 2.7 Two Approaches to Bargaining

| Bargaining Characteristic | Distributive Bargaining | Integrative Bargaining |

|---|---|---|

| Payoff structure | Fixed amount of resources to be divided | Variable amount of resources to be divided |

| Primary motivation | I win, you lose | Mutual benefit |

| Primary interests | Opposed to each other | Convergent with each other |

| Focus of relationships | Short term | Long term |

| Source: Organizational Behavior, OpenStax, CC BY 4.0. | ||

Distributed or Integrated Approach to Bargaining?

The negotiation process consists of identifying one’s desired goals—that is, what you are trying to get out of the exchange—and then developing suitable strategies aimed at reaching those goals. A key feature of one’s strategy is knowing one’s relative position in the bargaining process. That is, depending upon your relative position or strength, you may want to negotiate seriously or you may want to tell your opponent to “take it or leave it.” The dynamics of bargaining power can be extrapolated directly from the discussion of power and indicate several conditions affecting this choice. For example, you may wish to negotiate when you value the exchange, when you value the relationship, and when commitment to the issue is high. In the opposite situation, you may be indifferent to serious bargaining.

Table 2.8 When to Negotiate - Bargaining Strategies

| Characteristics of the Situation | Negotiate | Take It or Leave It |

|---|---|---|

| Value of exchange | High | Low |

| Commitment to a decision | High | Low |

| Trust Level | High | Low |

| Time | Ample | Pressing |

| Power distribution* | Low or balanced | High |

| Relationship between two parties | Important | Unimportant |

| *Indicates relative power distribution between the two parties; low indicates that one has little power in the situation, whereas high indicates that one has considerable power. | ||

| Source: Organizational Behavior, OpenStax, CC BY 4.0. | ||

Phases of Negotiation

In general, negotiation and bargaining are likely to has five stages. They are summarized in Figure 2.5 below. The presence and sequence of these stages are quite common across situations, although the length or importance of each stage can vary from situation to situation or from one culture to another (Graham, 1985). Let’s examine what commonly occurs in each of these phases of the negotiation process.

Phase 1: Investigation

The first step in negotiation is investigation or information gathering stage. This is a key stage that is often ignored. Surprisingly, the first place to begin is with yourself: What are your goals for the negotiation? What do you want to achieve? Once goals and objectives have been clearly established and the bargaining strategy is set, time is required to develop a suitable plan of action. Planning for negotiation requires a clear assessment of your own strengths and weaknesses as well as those of your opponents. Roy Lewicki and Joseph Litterer have suggested a format for preparation for negotiation (Graham, 1985; Lewicki et al., 2016; Baerman, 1986; Graham & Sano, 1989).

Phase 2: Determine Your BATNA

One important part of the investigation and planning phase is to determine your BATNA. Thinking through your BATNA is important to helping you decide whether to accept an offer you receive during the negotiation. You need to know what your alternatives are. If you have various alternatives, you can look at the proposed deal more critically. Could you get a better outcome than the proposed deal? Your BATNA will help you reject an unfavorable deal. On the other hand, if the deal is better than another outcome you could get (that is, better than your BATNA), then you should accept it. Think about it in common sense terms: When you know your opponent is desperate for a deal, you can demand much more. If it looks like they have a lot of other options outside the negotiation, you’ll be more likely to make concessions. The party with the best BATNA has the best negotiating position, so try to improve your BATNA whenever possible by exploring possible alternatives (Pinkley, 1995).

Let’s Focus: BATNA Best Practices

Here are some best practices for generating your BATNA:

Here are some best practices for generating your BATNA:

- Brainstorm a list of alternatives that you might conceivably take if the negotiation doesn’t lead to a favorable outcome for you.

- Improve on some of the more promising ideas and convert them into actionable alternatives.

- Identify the most beneficial alternative to be kept in reserve as a fall-back during the negotiation.

- Remember that your BATNA may evolve over time, so keep revising it to make sure it is still accurate.

- Don’t reveal your BATNA to the other party. If your BATNA turns out to be worse than what the other party expected, their offer may go down.

Sources: Adapted from information in Spangler (2003), Conflict Research Consortium, University of Colorado. (1998) and Venter (2003).

Phase 4: Presentation

Before the presentation of information, the parties come together and focus on getting to know and become comfortable with each other. At this stage, they do not focus directly on the task or issue of the negotiation. This is called non-task time. In Canadian culture, this stage is often filled with small talk. However, it is usually not very long and is not seen as important as other stages. As such, many Canadian textbooks (including this one) do not even include non-task time as a discrete phase in the negotiation process. North Americans use phrases such as “Let’s get down to business,” “I know you’re busy, so let’s get right to it,”. However, in other cultures, the non-task stage is often longer and of more importance because it is during this stage the relationship is established. It is the relationship more than the contract that determines the extent to which each party can trust the other to fulfill its obligations.

At the start of the presentation stage, parties also work together to define the ground rules and procedures for the negotiation. This is the time when you and the other party will come to agreement on questions like

- Who will do the negotiating—will we do it personally or invite a third party

- Where will the negotiation take place?

- Will there be time constraints placed on this negotiation process?

- Will there be any limits to the negotiation?

- If an agreement can’t be reached, will there be any specific process to handle that?

Finally, in the presentation phase, parties present the information that they have gathered in a way that supports their position. Once initial positions have been exchanged, the clarification and justification stage can begin. The parties can explain, clarify, bolster and justify their original position or demands. This is an opportunity to educate the other side on your position, and gain further understanding about the other party and how they feel about their side. You might each take the opportunity to explain how you arrived at your current position, and include any supporting documentation. Each party might take this opportunity to review the strategy they planned for the negotiation to determine if it’s still an appropriate approach.

This doesn’t need to be—and should not be—confrontational, though in some negotiations that’s hard to avoid. But if tempers are high moving into this portion of the negotiation process, then those emotions will start to come to a head here. It’s important for you to manage those emotions so serious bargaining can begin.

Phase 5: Bargaining

During the bargaining phase, each party discusses their goals and seeks to get an agreement.

At the heart of the bargaining phase are efforts to influence and persuade the other side. Generally, these efforts are designed to get the other party to reduce its demands or desires and to increase its acceptance of your demands or desires. There are a wide variety of influence tactics, including promises, threats, questions, and so on. The use of these tactics as well as their effectiveness is a function of several factors. First, the perceived or real power of one party relative to another is an important factor. For example, if one party is the only available supplier of a critical component, then threatening to go to a new supplier of that component unless the price is reduced is unlikely to be an effective influence tactic. Second, the effectiveness of a particular influence tactic is also a function of accepted industry and cultural norms. For example, if threats are an unacceptable form of influence, then their use could lead to consequences opposite from what is desired by the initiator of such tactics.

A natural part of this process is making concessions, namely, giving up one thing to get something else in return. Making a concession is not a sign of weakness—parties expect to give up some of their goals. Rather, concessions demonstrate cooperativeness and help move the negotiation toward its conclusion. Making concessions is particularly important in tense union-management disputes, which can get bogged down by old issues. Making a concession shows forward movement and process, and it allays concerns about rigidity or closed-mindedness. What would a typical concession be? Concessions are often in the areas of money, time, resources, responsibilities, or autonomy. When negotiating for the purchase of products, for example, you might agree to pay a higher price in exchange for getting the products sooner. Alternatively, you could ask to pay a lower price in exchange for giving the manufacturer more time or flexibility in when they deliver the product.

Consider This: Bargaining and Questions

Bargaining and the Importance of Asking Questions

One key to the bargaining phase is to ask questions. Don’t simply take a statement such as “we can’t do that” at face value. Rather, try to find out why the party has that constraint. Let’s take a look at an example.

Say that you’re a retailer and you want to buy patio furniture from a manufacturer. You want to have the sets in time for spring sales. During the negotiations, your goal is to get the lowest price with the earliest delivery date. The manufacturer, of course, wants to get the highest price with the longest lead time before delivery. As negotiations stall, you evaluate your options to decide what’s more important: a slightly lower price or a slightly longer delivery date? You do a quick calculation. The manufacturer has offered to deliver the products by April 30, but you know that some of your customers make their patio furniture selection early in the spring, and missing those early sales could cost you $1 million. So, you suggest that you can accept the April 30 delivery date if the manufacturer will agree to drop the price by $1 million.

“I appreciate the offer,” the manufacturer replies, “but I can’t accommodate such a large price cut.” Instead of leaving it at that, you ask, “I’m surprised that a 2-month delivery would be so costly to you. Tell me more about your manufacturing process so that I can understand why you can’t manufacture the products in that time frame.”

“Manufacturing the products in that time frame is not the problem,” the manufacturer replies, “but getting them shipped from Asia is what’s expensive for us.”

When you hear that, a light bulb goes off. You know that your firm has favorable contracts with shipping companies because of the high volume of business the firm gives them. You make the following counteroffer: “Why don’t we agree that my company will arrange and pay for the shipper, and you agree to have the products ready to ship on March 30 for $10.5 million instead of $11 million?” The manufacturer accepts the offer—the biggest expense and constraint (the shipping) has been lifted. You, in turn, have saved money as well.

Source: Adapted from Malhotra & Bazerman (2007).

Phase 6: Closure

The final stage of any negotiation is the closing. The closing may result in an acceptable agreement between the parties involved or it may result in failure to reach an agreement. Most negotiators assume that if their best offer has been rejected, there’s nothing left to do. You made your best offer and that’s the best you can do. The savviest of negotiators, however, see the rejection as an opportunity to learn. “What would it have taken for us to reach an agreement?” Sometimes at the end of negotiations, it’s clear why a deal was not reached. But if you’re confused about why a deal did not happen, consider making a follow-up call. Even though you may not win the deal back in the end, you might learn something that’s useful for future negotiations. What’s more, the other party may be more willing to disclose the information if they don’t think you’re in a “selling” mode.

The symbols that represent the close of a negotiation vary across cultures. For example, in Canada, a signed contract is often the symbol of a closed negotiation. At that point, “a deal is a deal” and failure to abide by the contents of the document is considered a breach of contract.

Consider This: Negotiation Tips

Tips for Negotiation Success

- Focus on agreement first. If you reach an impasse during negotiations, sometimes the best recourse is to agree that you disagree on those topics and then focus only on the ones that you can reach an agreement on. Summarize what you’ve agreed on, so that everyone feels like they’re agreeing, and leave out the points you don’t agree on. Then take up those issues again in a different context, such as over dinner or coffee. Dealing with those issues separately may help the negotiation process.

- Be patient. If you don’t have a deadline by which an agreement needs to be reached, use that flexibility to your advantage. The other party may be forced by circumstances to agree to your terms, so if you can be patient you may be able to get the best deal.

Whose reality? During negotiations, each side is presenting their case—their version of reality. Whose version of reality will prevail? Negotiation brings the relevant facts to the forefront and argues their merit. - Deadlines. Research shows that negotiators are more likely to strike a deal by making more concessions and thinking more creatively as deadlines loom than at any other time in the negotiation process.

- Be comfortable with silence. After you have made an offer, allow the other party to respond. Many people become uncomfortable with silence and feel they need to say something. Wait and listen instead.

Source: Adapted from information in Stuhlmacher et al. (1998).

Avoiding Common Mistakes in Negotiations

Below are several common mistakes that occur during the negotiation process

Winner’s Curse or Failing to Negotiate

Winner’s curse is said to occur when a negotiator makes a high offer quickly and it’s accepted just as quickly, making the negotiator feel as though they have been cheated. Lack of information and expertise are chief among the issues that cause this mistake.

Some people are taught to feel that negotiation is a conflict situation, and these individuals may tend to avoid negotiations to avoid conflict. Research shows that this negotiation avoidance is especially prevalent among women. For example, one study looked at students from Carnegie-Mellon who were getting their first job after earning a master’s degree. The study found that only 7% of the women negotiated their offer, while men negotiated 57% of the time (CNN, 2003). The result had profound consequences. Researchers calculate that people who routinely negotiate salary increases will earn over $1 million more by retirement than people who accept an initial offer every time without asking for more (Babcock & Lascheve, 2003). The good news is that it appears that it is possible to increase negotiation efforts and confidence by training people to use effective negotiation skills (Stevens et al., 1993).

It is important to note that women and men don’t necessarily negotiate differently; studies show that men negotiate slightly better outcomes than women do in the same situations, but the difference is often nominal. Many studies suggest that failing to negotiate may not explain gender differences in negotiation and that assertive behaviour on the part of female negotiators may result in backlash (Dannals et al., 2021). This is consistent with other research that women are more successful in negotiations when they are representing others rather than themselves (Shonk, 2022). Thus, gender differences in negotiation behaviour are an important area of continued investigation, but it is important to recognize that negotiations are only part of the explanation as to why there is a continued pay gap between women and men in Canada (To explore other factors see, for example, Moyer, 2019).

Letting Ego Get in the Way

When an negotiator is overconfident, they may put too much belief in their ability to be correct. This may lead to high anchors for their initial offers and adjustments. Irrational escalation of commitment occurs when the negotiator continues a course of action long after it’s been proven to be the wrong choice. Ego, distorted self-perception, and a need to “win” has lost many negotiators a fair deal.

Thinking only about yourself is another common mistake. People from societies like Canada that value individualism often tend to fall into a self-serving bias in which they over-inflate their own worth and discount the worth of others. This can be a disadvantage during negotiations. Instead, think about why the other person would want to accept the deal. People aren’t likely to accept a deal that doesn’t offer any benefit to them. Help them meet their own goals while you achieve yours. Integrative outcomes depend on having good listening skills, and if you are thinking only about your own needs, you may miss out on important opportunities. Remember that a good business relationship can only be created and maintained if both parties get a fair deal. This “softer” strategy of appealing to the greater good is often used by women to assert their needs while conforming to societal gender norms (Shonk, 2022).

Having Unrealistic Expectations

Susan Podziba, a professor of mediation at Harvard and MIT, plays broker for some of the toughest negotiations around, from public policy to marital disputes. She takes an integrative approach in the negotiations, identifying goals that are large enough to encompass both sides. As she puts it, “We are never going to be able to sit at a table with the goal of creating peace and harmony between fishermen and conservationists. But we can establish goals big enough to include the key interests of each party and resolve the specific impasse we are currently facing. Setting reasonable goals at the outset that address each party’s concerns will decrease the tension in the room, and will improve the chances of reaching an agreement.” Those who set unreasonable expectations are more likely to fail.

Getting Overly Emotional

Negotiations, by their very nature, are emotional. The findings regarding the outcomes of expressing anger during negotiations are mixed. Some researchers have found that those who express anger negotiate worse deals than those who do not and that during online negotiations, those parties who encountered anger were more likely to compete than those who did not (Kopelman et al., 2006; Friedman et al., 2004). In a study of online negotiations, words such as despise, disgusted, furious, and hate were related to a reduced chance of reaching an agreement (Brett et al., 2007). However, this finding may depend on individual personalities.

Research has also shown that those with more power may be more effective when displaying anger. The weaker party may perceive the anger as potentially signaling that the deal is falling apart and may concede items to help move things along (Van Kleef & Cote, 2007). This holds for online negotiations as well. In a study of 355 eBay disputes in which mediation was requested by one or both of the parties, similar results were found. Overall, anger hurts the mediation process unless one of the parties was perceived as much more powerful than the other party, in which case anger hastened a deal (Friedman et al., 2004). Another aspect of getting overly emotional is forgetting that facial expressions are universal across cultures, and when your words and facial expressions don’t match, you are less likely to be trusted (Hill, 2007; Holloway, 2007).

Letting Past Negative Outcomes Affect the Present Ones

Research shows that negotiators who had previously experienced ineffective negotiations were more likely to have failed negotiations in the future. Those who were unable to negotiate some type of deal in previous negotiation situations tended to have lower outcomes than those who had successfully negotiated deals in the past (O’Connor et al., 2005). The key to remember is that there is a tendency to let the past repeat itself. Being aware of this tendency allows you to overcome it. Be vigilant to examine the issues at hand and not to be overly swayed by past experiences, especially while you are starting out as a negotiator and have limited experiences.

Mythical Fixed Pie

Taking a distributive approach to bargaining can lead to failure when the negotiator assumes that what’s good for the other side is bad for their side. Competitiveness can get in the way of coming up with a creative solution that benefits all parties.

Third-Party Negotiations

For every negotiation that goes well, there is one that is not successful. In the last section, we talked about some of the ways a negotiation can go wrong. At this point, a third party negotiator may be brought in to help parties find an agreement. There are four basic third-party negotiator roles: consultant, conciliator, mediator, and arbitrator. Each of these third-party negotiator roles provides a specific service for the parties who have employed them. Let’s take a look at each role and how it functions.

Consultants

A consultant is a third-party negotiator who is skilled in conflict management and can add their knowledge and skill to the mix to help the negotiating parties arrive at a conclusion. A consultant will help parties learn to understand and work with each other, so this approach has a longer-term focus to build bridges between the conflicting parties.

A real estate agent is an excellent example of a third-party negotiator who is considered a consultant. People who are looking to buy a house might not understand the ins and outs of money deposit, title insurance and document fees. A real estate agent will not only explain all of that, but prepare the purchase agreement and make the offer on behalf of their client.

Conciliators

A conciliator is a trusted third party who provides communication between the negotiating parties. This approach is used frequently in international, labour, family and community disputes. Conciliators often engage in fact finding, interpreting messages, and persuading parties to develop an agreement. Very often conciliators act only as a communication conduit between the parties and don’t actually perform any specific negotiation duties.

Mediators

A mediator is a neutral, third party who helps facilitate a negotiated solution. The mediator may use reasoning and persuasion, or may suggest alternatives. Parties using a mediator must be motivated to settle the issue, or mediation will not work. Mediation differs from arbitration in that there is not a guaranteed settlement.

Mediators are most commonly found as third-party negotiators for labour disputes. If a labour union and a company come together to discuss contract terms, a mediator may be employed to assist in ironing out all the issues that need extra attention—like vacation days and percentage of raise.

One of the advantages of mediation is that the mediator helps the parties design their own solutions, including resolving issues that are important to both parties, not just the ones under specific dispute. Interestingly, sometimes mediation solves a conflict even if no resolution is reached. Here’s a quote from Avis Ridley-Thomas, the founder and administrator of the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Dispute Resolution Program, who explains, “Even if there is no agreement reached in mediation, people are happy that they engaged in the process. It often opens up the possibility for resolution in ways that people had not anticipated” (Layne, 1999). An independent survey showed 96 percent of all respondents and 91 percent of all charging parties who used mediation would use it again if offered (Layne, 1999).

You Know It’s Time for a Mediator When…

- The parties are unable to find a solution themselves.

- Personal differences are standing in the way of a successful solution.

- The parties have stopped talking with one another.

- Obtaining a quick resolution is important.

Source: Adapted from information in Crawley (1994).

Arbitrators

In contrast to mediation, in which parties work with the mediator to arrive at a solution, in arbitration the parties submit the dispute to the third-party arbitrator. It is the arbitrator who makes the final decision. The arbitrator is a neutral third party, but the decision made by the arbitrator is final (the decision is called the “award”). Awards are made in writing and are binding to the parties involved in the case (American Arbitration Association, 2007). It is common to see mediation followed by arbitration. Arbitration can be voluntary or forced on the parties of a negotiation by law or contract. The arbitrator’s power varies according to the rules set by the negotiators. The arbitrator might be limited to choosing one of the party’s offers and enforcing it, or they may be able to freely suggest other solutions. Arbitration is often used in union-management grievance conflicts.

Adapted Works

“Conflict and Negotiations” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

“Conflicts and Negotiations” in Organizational Behavior by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Negotiations” in Human Relations by Saylor Academy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

“Conflict and Negotiation” in Organizational Behaviour by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

American Arbitration Association. (2007). Arbitration and mediation. Retrieved November 11, 2008, from http://www.adr.org/arb_med

Babcock, L., & Lascheve, S. (2003). Women don’t ask: Negotiation and the gender divide. Princeton University Press.

Brett, J. M., Olekalns, M., Friedman, R., Goates, N., Anderson, C., & Lisco, C. C. (2007). Sticks and stones: Language, face, and online dispute resolution. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 85–99.

Crawley, J. (1994). Constructive conflict management. Pfeiffer.

Conflict Research Consortium, University of Colorado. (1998). Limits to agreement: Better alternatives. http://www.colorado.edu/conflict/peace/problem/batna.htm

CNN. (2003, August 21). Interview with Linda Babcock. http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0308/21/se.04.html

Dannals, J. E., Zlatev, J. J., Halevy, N., & Neale, M. A. (2021). The dynamics of gender and alternatives in negotiation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(11), 1655–1672. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000867

Edwards, D. D. (2013, March 18). Getting to yes. De Dicto. http://is.gd/ys8Hny

Fisher, R. & Ury, W. (1981). Getting to yes: negotiating agreement without giving in. Penguin.

Fisher, R., Ury, W. L., & Patton, B. (2012). Getting to yes. Penguin.

Friedman, R., Anderson, C., Brett, J., Olekalns, M., Goates, N., & Lisco, C. C. (2004). The positive and negative effects of anger on dispute resolution: Evidence from electronically mediated disputes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 369–376.

Graham, J. (1985). The influence of culture on business negotiations. Journal of International Business Studies, 16(1), 81–96.

Graham, J. & Sano, Y. (1989). Smart bargaining. Harper & Row.

Hill, D. (2007). Emotionomics: Winning hearts and minds. Adams Business & Professional.

Holloway, L. (2007, December). Mixed signals: Are you saying one thing, while your face says otherwise? Entrepreneur, 35, 49.

Kopelman, S., Rosette, A. S., & Thompson, L. (2006). The three faces of Eve: An examination of the strategic display of positive, negative, and neutral emotions in negotiations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 99, 81–101.

Layne, A. (1999, November). Conflict resolution at Greenpeace? Fast Company. http://www.fastcompany.com/articles/1999/12/rick_hind.html

Lewicki, R., J, Barry, B., & Saunders, D. M. (2016). Essentials of negotiation. McGraw Hill.

Malhotra, D., & Bazerman, M. H. (2007, September). Investigative negotiation. Harvard Business Review, 85, 72.

Moyer, M. (2019). Measuring and analyzing the gender pay gap: A conceptual and methodological overview. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-20-0002/452000022019001-eng.htm

O’Connor, K. M., Arnold, J. A., & Burris, E. R. (2005). Negotiators’ bargaining histories and their effects on future negotiation performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 350–362.

Pinkley, R. L. (1995). Impact of knowledge regarding alternatives to settlement in dyadic negotiations: Whose knowledge counts? Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 403–417.

Shonk, K. (2022, February 1). Negotiating tips for women negotiators to achieve results at the negotiation table. Program on Negotiation Daily Blog. https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/leadership-skills-daily/women-and-negotiation-leveling-the-playing-field/

Spangler, B. (2003, June). Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA). Beyond Intractability. http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/batna/

Stevens, C. K., Bavetta, A. G., & Gist, M. E. (1993). Gender differences in the acquisition of salary negotiation skills: The role of goals, self-efficacy, and perceived control. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 723–735.

Stuhlmacher, A. F., Gillespie, T. L., & Champagne, M. V. (1998). The impact of time pressure in negotiation: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Conflict Management, 9, 97–116.

Thompson, L. (1990). Negotiation behavior and outcomes: Empirical evidence and theoretical issues. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 515–532.

Thompson, L., & Hrebec, D. (1996). Lose-lose agreements in interdependent decision making. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 396–409.

Van Kleef, G. A., & Cote, S. (2007). Expressing anger in conflict: When it helps and when it hurts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1557–1569.

Venter, D. (2003). What is a BATNA? Negotiation Europe. http://www.negotiationeurope.com/articles/batna.html