3.1 Organizational Culture

In this section:

Organizational Culture Defined

These values have a strong influence on employee behavior as well as organizational performance. In fact, the term organizational culture was made popular in the 1980s when Peters and Waterman’s best-selling book In Search of Excellence made the argument that company success could be attributed to an organizational culture that was decisive, customer oriented, empowering, and people oriented. Since then, organizational culture has become the subject of numerous research studies, books, and articles.

Culture is by and large invisible to individuals. Even though it affects all employee behaviors, thinking, and behavioral patterns, individuals tend to become more aware of their organization’s culture when they have the opportunity to compare it to other organizations. If you have worked in multiple organizations, you can attest to this. Maybe the first organization you worked was a place where employees dressed formally. It was completely inappropriate to question your boss in a meeting; such behaviors would only be acceptable in private. It was important to check your email at night as well as during weekends or else you would face questions on Monday about where you were and whether you were sick. Contrast this company to a second organization where employees dress more casually. You are encouraged to raise issues and question your boss or peers, even in front of clients. What is more important is not to maintain impressions but to arrive at the best solution to any problem. It is widely known that family life is very important, so it is acceptable to leave work a bit early to go to a family event. Additionally, you are not expected to do work at night or over the weekends unless there is a deadline. These two hypothetical organizations illustrate that organizations have different cultures, and culture dictates what is right and what is acceptable behavior as well as what is wrong and unacceptable.

Organizational Subcultures

So far, we have assumed that a company has a single culture that is shared throughout the organization. However, you may have realized that this is an oversimplification. In reality there might be multiple cultures within any given organization. For example, people working on the sales floor may experience a different culture from that experienced by people working in the warehouse. A culture that emerges within different departments, branches, or geographic locations is called a subculture. Subcultures may arise from the personal characteristics of employees and managers, as well as the different conditions under which work is performed. Within the same organization, marketing and manufacturing departments often have different cultures such that the marketing department may emphasize innovativeness, whereas the manufacturing department may have a shared emphasis on detail orientation.

In an interesting study, researchers uncovered five different subcultures within a single police organization. These subcultures differed depending on the level of danger involved and the type of background experience the individuals held, including “crime-fighting street professionals” who did what their job required without rigidly following protocol and “anti-military social workers” who felt that most problems could be resolved by talking to the parties involved (Jermier et al., 1991). Research has shown that employee perceptions regarding subcultures were related to employee commitment to the organization (Lok et al., 2005). Therefore, in addition to understanding the broader organization’s values, managers will need to make an effort to understand subculture values to see its impact on workforce behavior and attitudes. Moreover, as an employee, you need to understand the type of subculture in the department where you will work in addition to understanding the company’s overall culture.

Sometimes, a subculture may take the form of a counterculture. Defined as shared values and beliefs that are in direct opposition to the values of the broader organizational culture (Kerr & Slocum, 2005), countercultures are often shaped around a charismatic leader. For example, within a largely bureaucratic organization, an enclave of innovativeness and risk taking may emerge within a single department. A counterculture may be tolerated by the organization as long as it is bringing in results and contributing positively to the effectiveness of the organization. However, its existence may be perceived as a threat to the broader organizational culture.

Levels of Organizational Culture

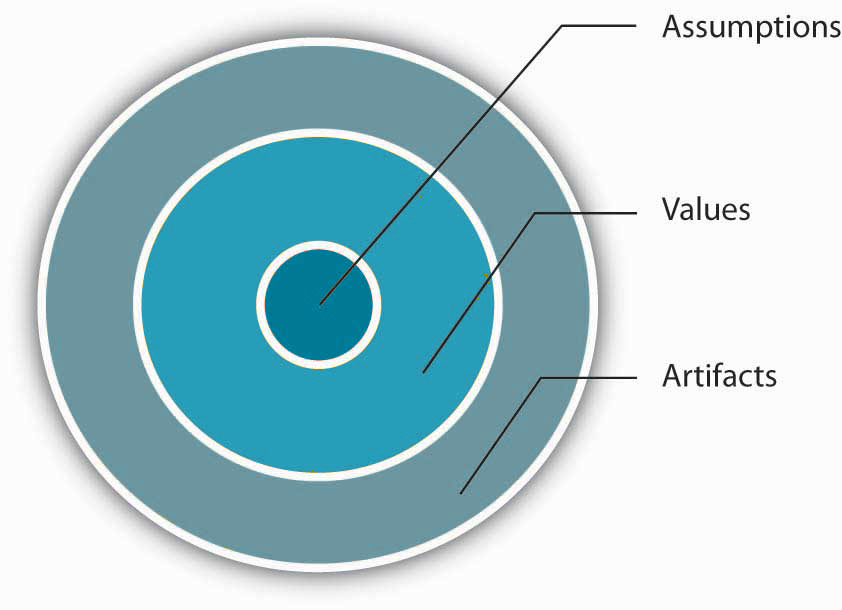

Organizational culture consists of some aspects that are relatively more visible, as well as aspects that may lie below one’s conscious awareness. Organizational culture can be thought of as consisting of three interrelated levels (Schein, 1992).

At the deepest level, below our awareness lie basic assumptions. Assumptions are taken for granted, and they reflect beliefs about human nature and reality. At the second level, values exist. Values are shared principles, standards, and goals. Finally, at the surface we have artifacts, or visible, tangible aspects of organizational culture. If assumptions and values are not shared by everyone or there are basic differences in assumptions between departments or subcultures, this may be a source of conflict within the organization. Similarly, differences in your own personal assumptions and values can create feelings of discomfort and intrapersonal conflict if they do not align with organizational culture.

For example, in an organization one of the basic assumptions employees and managers share might be that happy employees benefit their organizations. This assumption could translate into values such as social equality, high quality relationships, and having fun. The artifacts reflecting such values might be an executive “open door” policy, an office layout that includes open spaces and gathering areas equipped with pool tables, and frequent company picnics in the workplace. For example, Alcoa Inc. designed their headquarters to reflect the values of making people more visible and accessible, and to promote collaboration (Stegmeier, 2008).

Understanding the organization’s culture may start from observing its artifacts: the physical environment, employee interactions, company policies, reward systems, and other observable characteristics. When you are interviewing for a position, observing the physical environment, how people dress, where they relax, and how they talk to others is definitely a good start to understanding the company’s culture. However, simply looking at these tangible aspects is unlikely to give a full picture of the organization. An important chunk of what makes up culture exists below one’s degree of awareness. The values and, at a deeper level, the assumptions that shape the organization’s culture can be uncovered by observing how employees interact and the choices they make, as well as by inquiring about their beliefs and perceptions regarding what is right and appropriate behavior.

Let’s Practice: The Organizational Cultural Iceberg Activity

These levels of organizational culture are sometimes portrayed as an iceberg, with artifacts appearing as the tip of the iceberg above the surface of the water, with deeper layers of values and assumptions being placed under the surface of the water. Practice your understanding of these elements of culture by dragging the various elements of organizational culture either above or below the surface of the water.

These levels of organizational culture are sometimes portrayed as an iceberg, with artifacts appearing as the tip of the iceberg above the surface of the water, with deeper layers of values and assumptions being placed under the surface of the water. Practice your understanding of these elements of culture by dragging the various elements of organizational culture either above or below the surface of the water.

Strength of Culture

A strong culture is one that is shared by organizational members (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987; Chatman & Cha, 2003). In other words, if most employees in the organization show consensus regarding the values of the company, it is possible to talk about the existence of a strong culture. A culture’s content is more likely to affect the way employees think and behave when the culture in question is strong. For example, cultural values emphasizing customer service will lead to higher quality customer service if there is widespread agreement among employees on the importance of customer service-related values (Schneider et al., 2002).

It is important to realize that a strong culture may act as an asset or liability for the organization, depending on the types of values that are shared. For example, imagine a company with a culture that is strongly outcome oriented. If this value system matches the organizational environment, the company outperforms its competitors. On the other hand, a strong outcome-oriented culture coupled with unethical behaviors and an obsession with quantitative performance indicators may be detrimental to an organization’s effectiveness. An extreme example of this dysfunctional type of strong culture is Enron.

A strong culture may sometimes outperform a weak culture because of the consistency of expectations. In a strong culture, members know what is expected of them, and the culture serves as an effective control mechanism on member behaviors. Research shows that strong cultures lead to more stable corporate performance in stable environments. However, in volatile environments, the advantages of culture strength disappear (Sorensen, 2002).

One limitation of a strong culture is the difficulty of changing a strong culture. If an organization with widely shared beliefs decides to adopt a different set of values, unlearning the old values and learning the new ones will be a challenge, because employees will need to adopt new ways of thinking, behaving, and responding to critical events. A strong culture may also be a liability during a merger. During mergers and acquisitions, companies inevitably experience a clash of cultures, as well as a clash of structures and operating systems.

Culture clash becomes more problematic if both parties have unique and strong cultures. For example, during the merger of Daimler AG with Chrysler Motors LLC to create DaimlerChrysler AG, the differing strong cultures of each company acted as a barrier to effective integration. Daimler had a strong engineering culture that was more hierarchical and emphasized routinely working long hours. Daimler employees were used to being part of an elite organization, evidenced by flying first class on all business trips. On the other hand, Chrysler had a sales culture where employees and managers were used to autonomy, working shorter hours, and adhering to budget limits that meant only the elite flew first class. The different ways of thinking and behaving in these two companies introduced a number of unanticipated problems during the integration process (Badrtalei & Bates, 2007; Bower, 2001). Differences in culture may be part of the reason that, in the end, the merger didn’t work out.

The Importance of Organizational Culture

An organization’s culture may be one of its strongest assets, as well as its biggest liability. In fact, it has been argued that organizations that have a rare and hard-to-imitate organizational culture benefit from it as a competitive advantage (Barney, 1986). Kihlstrom (2020) goes as far to assert that culture is an important as strategy when it comes to organizational performance.

Company performance may benefit from the benefits of shared values provided by culture when they have a match to the company and the industry at large (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987). For example, if a company is in the high-tech industry, having a culture that encourages innovativeness and adaptability will support its performance. However, if a company in the same industry has a culture characterized by stability, a high respect for tradition, and a strong preference for upholding rules and procedures, the company may suffer as a result of its culture. In other words, just as having the “right” culture may be a competitive advantage for an organization, having the “wrong” culture may lead to performance difficulties, may be responsible for organizational failure, and may act as a barrier preventing the company from changing and taking risks.

In addition to having implications for organizational performance, organizational culture is an effective control mechanism for dictating employee behavior. Culture is in fact a more powerful way of controlling and managing employee behaviors than organizational rules and regulations. When problems are unique, rules tend to be less helpful. Organizations can (and should) create formalized policies and procedures to deal with conflict (We will talk more about policies in future sections of this chapter). In addition, having a culture of respect, civility, and inclusion will help to keep workplace conflict functional and productive.

Adapted Works

“Organizational Culture” in Organizational Behavior by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

Arogyaswamy, B., & Byles, C. M. (1987). Organizational culture: Internal and external fits. Journal of Management, 13, 647–658.

Badrtalei, J., & Bates, D. L. (2007). Effect of organizational cultures on mergers and acquisitions: The case of DaimlerChrysler. International Journal of Management, 24, 303–317.

Barney, J. B. (1986). Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review, 11, 656–665.

Bower, J. L. (2001). Not all M&As are alike—and that matters. Harvard Business Review, 79, 92–101.

Chatman, J. A., & Cha, S. E. (2003). Leading by leveraging culture. California Management Review, 45(4), 20–34.

Jermier, J. M., Slocum, J. W., Jr., Fry, L. W., & Gaines, J. (1991). Organizational subcultures in a soft bureaucracy: Resistance behind the myth and facade of an official culture. Organization Science, 2, 170–194.

Kerr, J., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (2005). Managing corporate culture through reward systems. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 130–138.

Kihlstrom, G. (2020, January 31). How to define a successful company culture. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2020/01/31/how-to-define-a-successful-company-culture/?sh=4f8066221d60

Lok, P., Westwood, R., & Crawford, J. (2005). Perceptions of organisational subculture and their significance for organisational commitment. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54, 490–514.

Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass.

Schneider, B., Salvaggio, A., & Subirats, M. (2002). Climate strength: A new direction for climate research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 220–229.

Sorensen, J. B. (2002). The strength of corporate culture and the reliability of firm performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 70–91.

Stegmeier, D. (2008). Innovations in office design: The critical influence approach to effective work environments. John Wiley & Sons.