7.1 Emotions and Intelligence

In this section:

Components of Emotion

The topic of this section is affect, defined as the experience of feeling or emotion. Affect is an essential part of the study of conflict. As we will see, affect guides behaviour, helps us make decisions, and has a major impact on our mental and physical health.

The two fundamental components of affect are emotions and motivation. Both of these words have the same underlying Latin root, meaning “to move.” In contrast to cognitive processes that are calm, collected, and frequently rational, emotions and motivations involve arousal. Because they involve arousal, emotions and motivations are “hot” — they “charge,” “drive,” or “move” our behaviour. We will talk more about motivation in Chapter 8.

The Physiology of Emotion

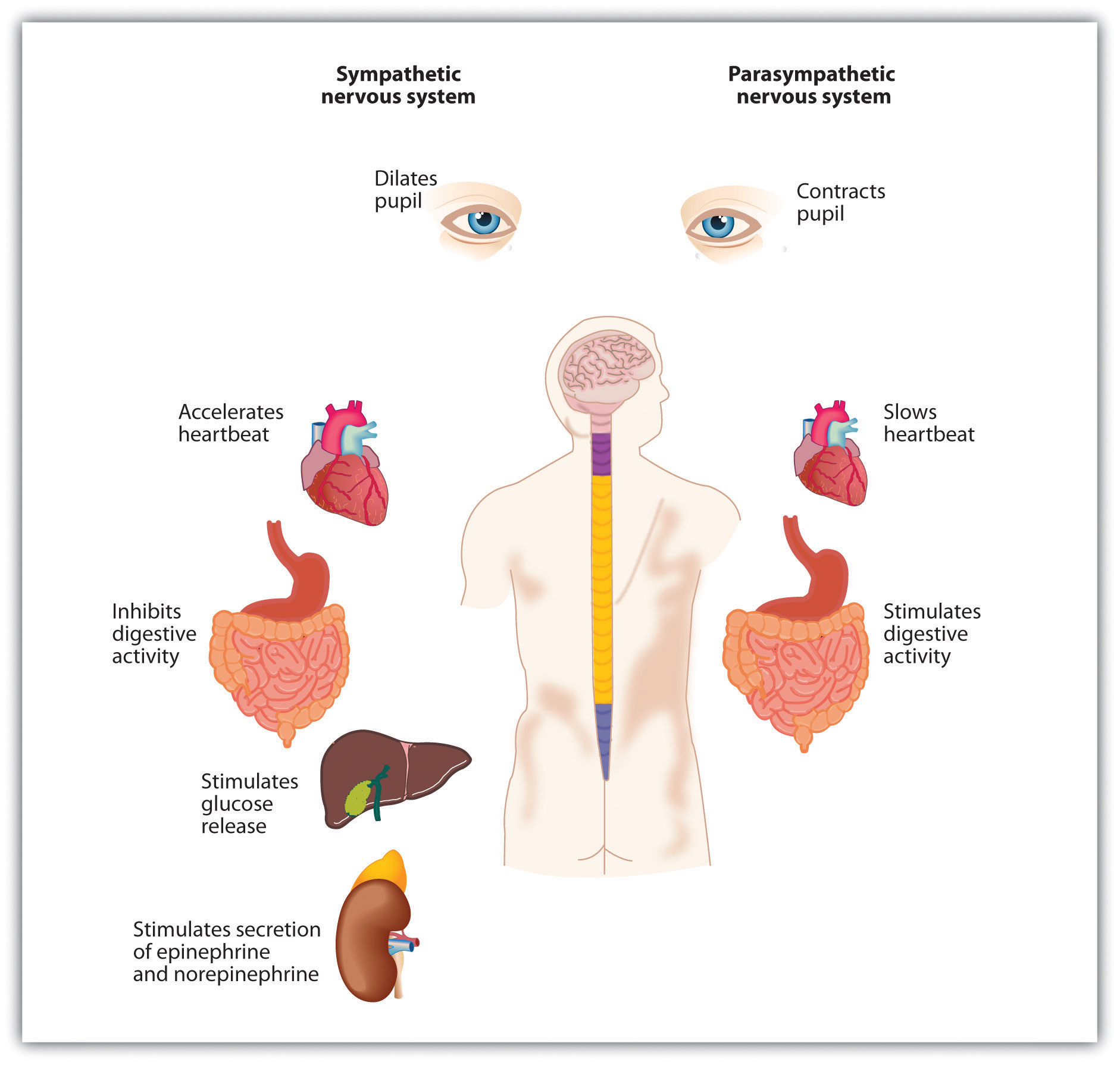

Our emotions are determined in part by responses of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS)—the division of the autonomic nervous system that is involved in preparing the body to respond to threats by activating the organs and the glands in the endocrine system. The SNS works in opposition to the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), the division of the autonomic nervous system that is involved in resting, digesting, relaxing, and recovering. When it is activated, the SNS provides us with energy to respond to our environment. The liver puts extra sugar into the bloodstream, the heart pumps more blood, our pupils dilate to help us see better, respiration increases, and we begin to perspire to cool the body. The sympathetic nervous system also acts to release stress hormones including epinephrine and norepinephrine. At the same time, the action of the PNS is decreased.

We experience the activation of the SNS as arousal—changes in bodily sensations, including increased blood pressure, heart rate, perspiration, and respiration. Arousal is the feeling that accompanies strong emotions. I’m sure you can remember a time when you were in love, angry, afraid, or very sad and experienced the arousal that accompanied the emotion. Perhaps you remember feeling flushed, feeling your heart pounding, feeling sick to your stomach, or having trouble breathing.

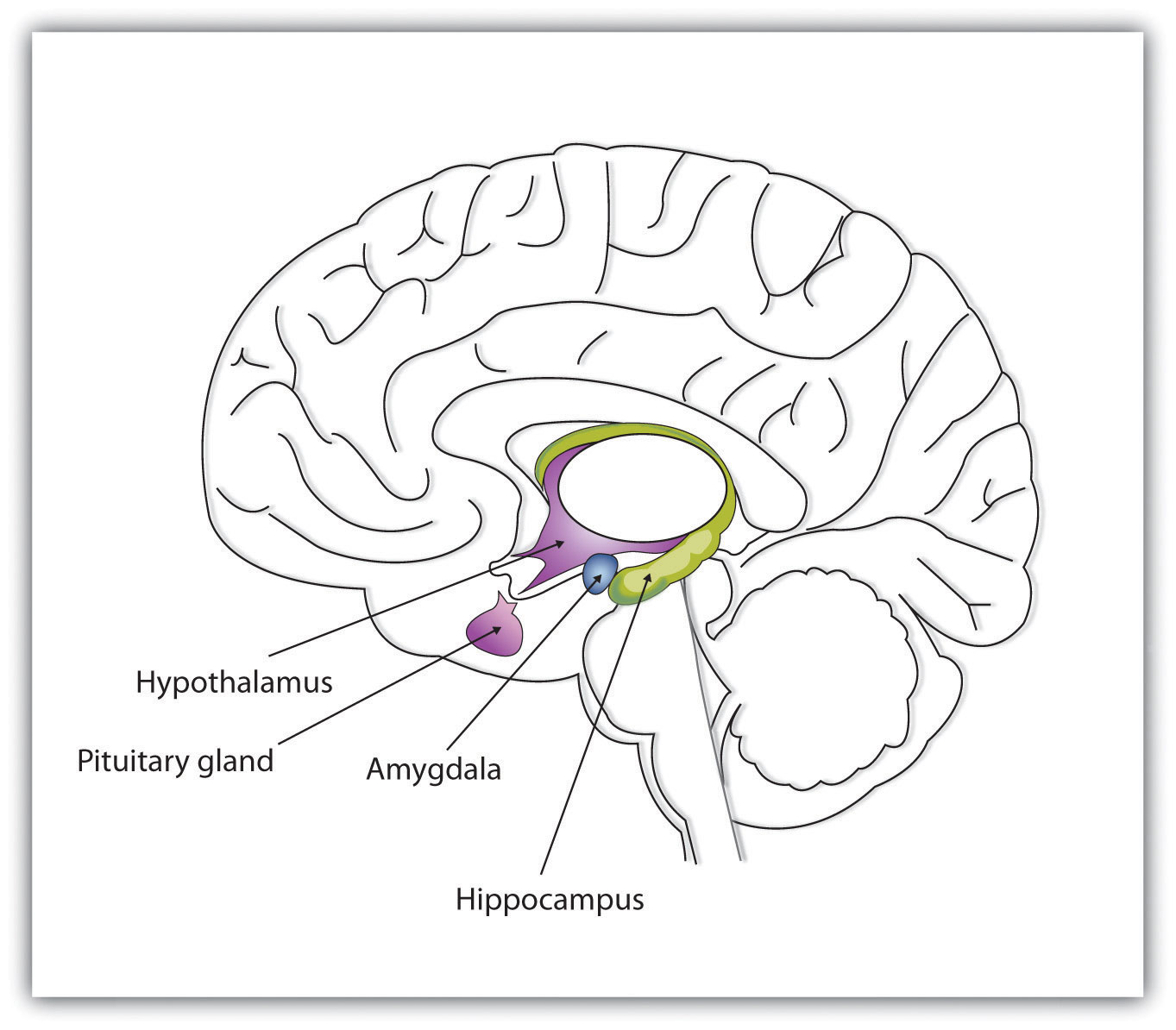

The arousal that we experience as part of our emotional experience is caused by the activation of the sympathetic nervous system. The experience of emotion is also controlled in part by one of the evolutionarily oldest parts of our brain—the part known as the limbic system—which includes several brain structures that help us experience emotion. Particularly important is the amygdala, the region in the limbic system that is primarily responsible for regulating our perceptions of, and reactions to, aggression and fear. The amygdala has connections to other bodily systems related to emotions, including the facial muscles, which perceive and express emotions, and it also regulates the release of neurotransmitters related to stress and aggression (Best, 2009). When we experience events that are dangerous, the amygdala stimulates the brain to remember the details of the situation so that we learn to avoid it in the future (Sigurdsson et al., 2007; Whalen et al., 2001).

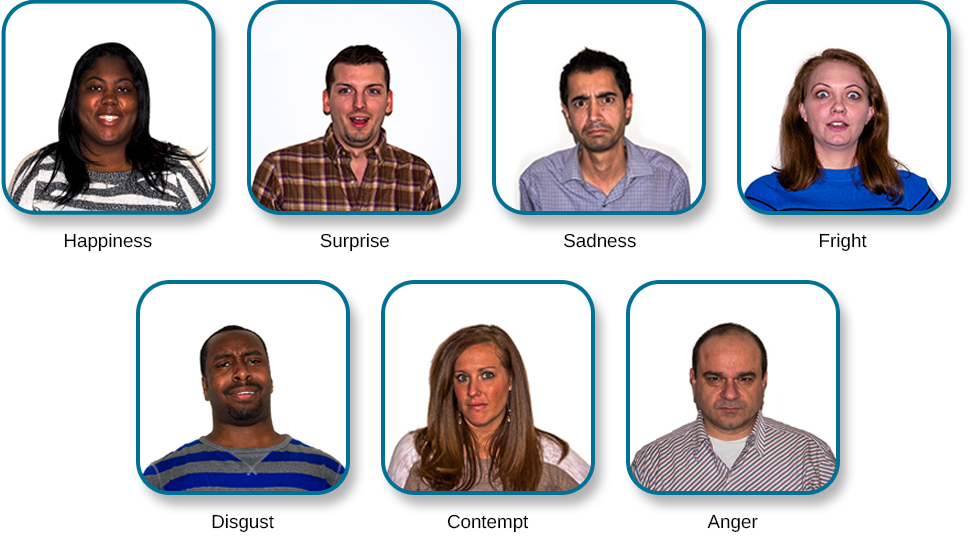

The most fundamental emotions, known as the basic emotions, are those of anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. The basic emotions have a long history in human evolution, and they have developed in large part to help us make rapid judgments about stimuli and to quickly guide appropriate behaviour (LeDoux, 2000). The basic emotions are determined in large part by one of the oldest parts of our brain, the limbic system, including the amygdala, the hypothalamus, and the thalamus. Because they are primarily evolutionarily determined, the basic emotions are experienced and displayed in much the same way across cultures (Ekman, 1992; Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002; Fridlund et al., 1987).

Cognitive Components of Emotions

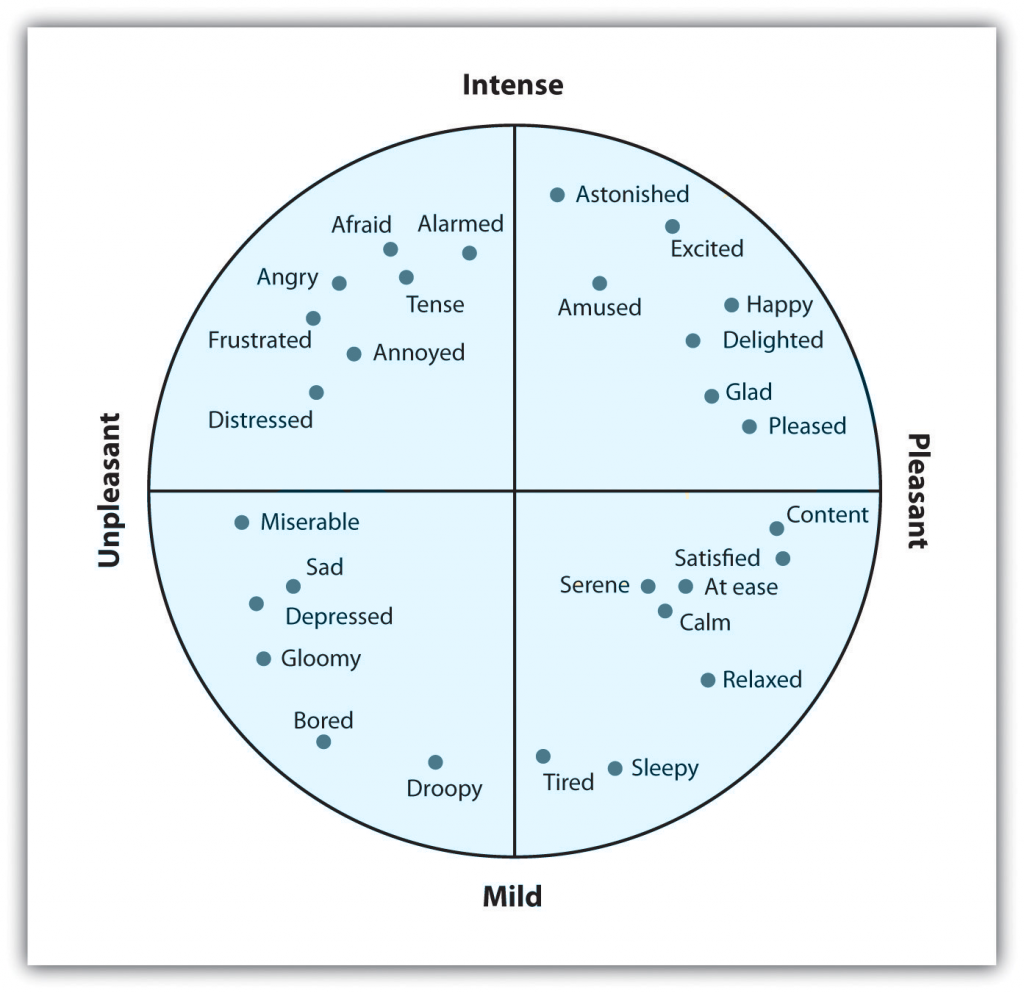

Not all of our emotions come from the old parts of our brain; we also interpret our experiences to create a more complex array of emotional experiences. For instance, the amygdala may sense fear when it senses that the body is falling, but that fear may be interpreted completely differently, perhaps even as excitement, when we are falling on a roller-coaster ride than when we are falling from the sky in an airplane that has lost power. The cognitive interpretations that accompany emotions— known as cognitive appraisal — allow us to experience a much larger and more complex set of secondary emotions (see Figure 7.2). Although they are in large part cognitive, our experiences of the secondary emotions are determined in part by arousal, as seen on the vertical axis of Figure 7.3, and in part by their valence — that is, whether they are pleasant or unpleasant feelings — as seen on the horizontal axis of Figure 7.3.

When you succeed in reaching an important goal, you might spend some time enjoying your secondary emotions, perhaps the experience of joy, satisfaction, and contentment, but when your close friend wins a prize that you thought you had deserved, you might also experience a variety of secondary emotions — in this case, the negative ones like feeling angry, sad, resentful, or ashamed. You might mull over the event for weeks or even months, experiencing these negative emotions each time you think about it (Martin & Tesser, 2006).

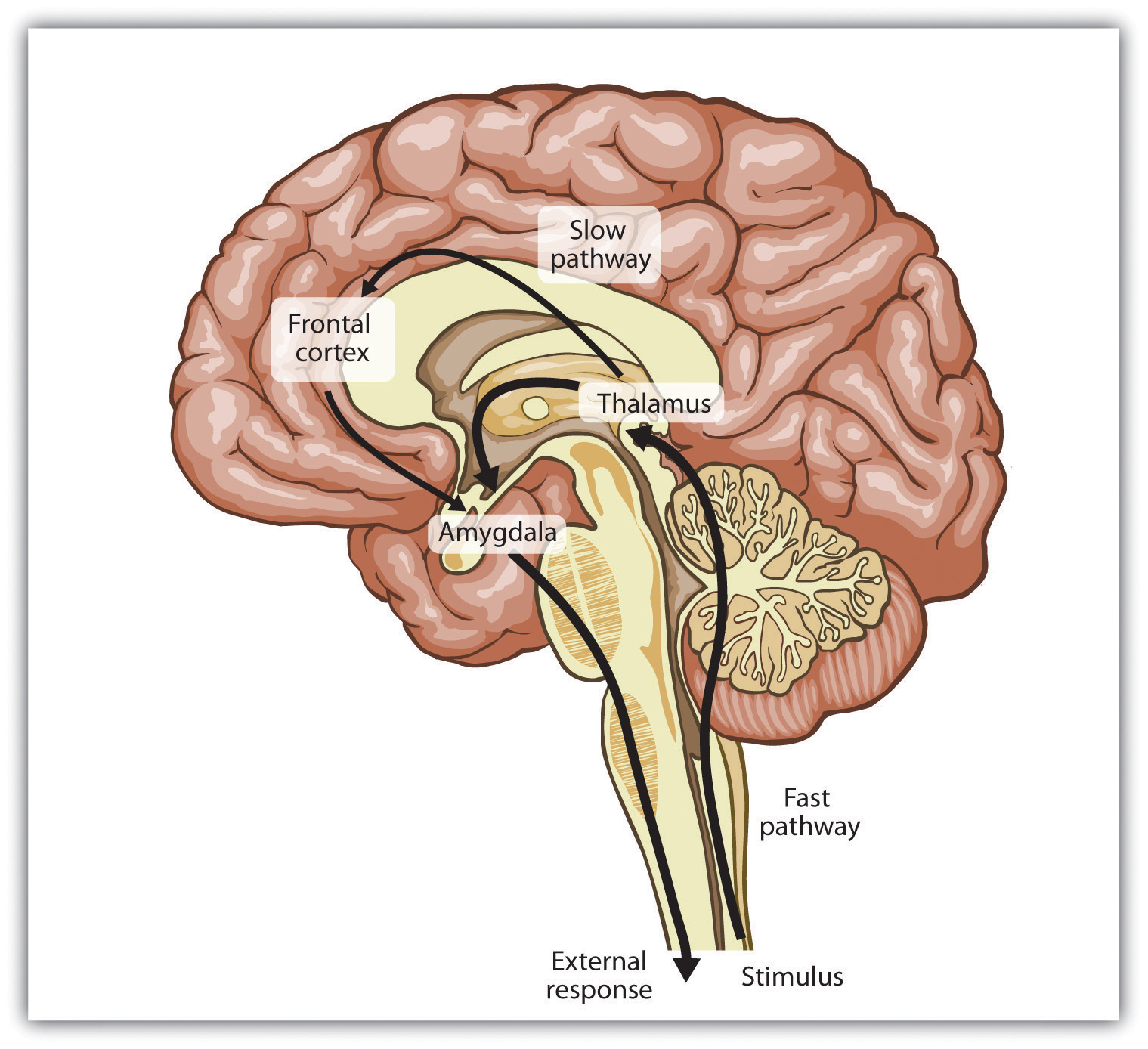

The distinction between the primary and the secondary emotions is paralleled by two brain pathways: a fast pathway and a slow pathway (Damasio, 2000; LeDoux, 2000; Ochsner et al., 2002). The thalamus acts as the major gatekeeper in this process (see Figure 7.4). Our response to the basic emotion of fear, for instance, is primarily determined by the fast pathway through the limbic system. When a car pulls out in front of us on the highway, the thalamus activates and sends an immediate message to the amygdala. We quickly move our foot to the brake pedal. Secondary emotions are more determined by the slow pathway through the frontal lobes in the cortex. When we stew in jealousy over the loss of a partner to a rival or recollect our win in the big tennis match, the process is more complex. Information moves from the thalamus to the frontal lobes for cognitive analysis and integration, and then from there to the amygdala. We experience the arousal of emotion, but it is accompanied by a more complex cognitive appraisal, producing more refined emotions and behavioural responses.

Although emotions might seem to you to be more frivolous or less important in comparison to our more rational cognitive processes, both emotions and cognitions can help us make effective decisions. In some cases, we take action after rationally processing the costs and benefits of different choices, but in other cases, we rely on our emotions. Emotions become particularly important in guiding decisions when the alternatives between many complex and conflicting alternatives present us with a high degree of uncertainty and ambiguity, making a complete cognitive analysis difficult. In these cases, we often rely on our emotions to make decisions, and these decisions may in many cases be more accurate than those produced by cognitive processing (Damasio, 1994; Dijksterhuis et al., 2006; Nordgren & Dijksterhuis, 2009; Wilson & Schooler, 1991).

Consider This: Dan Siegal on Flipping Your Lid

We’ve talked about the slow and fast routes in the brain for processing emotions. Remember, our emotions taking the fast route go to the limbic system. The amygdala in the brain can trigger our fight or flight reaction and make it difficult for the slow route to the cortex to take a more reasoned approach to a situation.

We’ve talked about the slow and fast routes in the brain for processing emotions. Remember, our emotions taking the fast route go to the limbic system. The amygdala in the brain can trigger our fight or flight reaction and make it difficult for the slow route to the cortex to take a more reasoned approach to a situation.

Dr. Dan Siegal is a researcher who examines emotions, trauma, and the brain. He uses the term “flipping your lid” to talk about how the brain acts differently when we are experiencing strong emotions like anger.

Please watch the video clip below to see this model in action:

Video: Dr. Dan Siegel’s Hand Model of the Brain [8:15]. Captions are available on YouTube.

Siegal suggests a number of strategies for parents and children to “unflip their lid” and reintegrate these areas of our brain including “name it to tame it”. He posits that awareness and communication about our emotional state is one of the first steps we can take to regain control and begin repair after we’ve lost control.

References

Siegal, D. (2021). Dr. Dan Siegal’s hand model of the brain. Mind Your Brain. https://drdansiegel.com/hand-model-of-the-brain/

The Brain During Conflict

Have you ever had the experience, where after you’ve been in a conflict, you can’t remember what you said OR you can’t figure out why you said what you said? You are not alone. This occurs when we are experiencing a defensive response. The neuroscience of conflict and defensive responses is fascinating! For the purposes of this book we will only touch the surface of this concept, but I think that it is an important part of learning to recognize and manage our own behaviour in conflict.

When we experience conflict we all have some kind of physical tells that we are experiencing stress or being triggered. This could be rosy cheeks, sweaty palms or pits, queazy stomachs, or clenched teeth. If you aren’t sure what your physical tells are, pay close attention the next time you feel frustrated, stressed out, or find yourself in the middle of a conflict. These are the physical symptoms of conflict. But what is going on in our brains?

When you first experience conflict, your limbic system (this system includes our amygdala which plays an important part in regulating emotions and behaviors and is typically talked about as the place where our “Fight, Flight, or Freeze” responses live) scans the environment for threats or rewards. Depending on the intensity of conflict you are having, you could experience an Amygdala Hijacking where you can no longer access the prefrontal cortex, this is the part of the brain that regulates empathy, decision making, problem solving, and much more. You can often see people experience an amygdala hijacking, some people lash out (fight), some people run away (flight), and some people sink into themselves (freeze).

Next, the thalamus, your brains perception center starts to work on interpreting the stimuli created by the conflict. This is where our regularly wrong assumptions come from. From this, our brain creates a story or a narrative of the entire conflict from beginning, middle, to end (even if we don’t have all the information necessary for the complete story).

Essentially, our brains are wired to react to conflict not to respond productively. It’s important to understand that we are all allowed to be emotional beings. Being emotional is an inherent part of being a human. For this reason, it’s important to avoid phrases like “don’t feel that way” or “they have no right to feel that way.” Again, our emotions are our emotions, and, when we negate someone else’s emotions, we are negating that person as an individual and taking away their right to emotional responses. At the same time, though, no one else can make you “feel” a specific way. Our emotions are our emotions. They are how we interpret and cope with life. A person may set up a context where you experience an emotion, but you are the one who is still experiencing that emotion and allowing yourself to experience that emotion. If you don’t like “feeling” a specific way, then change it. We all have the ability to alter our emotions. Altering our emotional states (in a proactive way) is how we get through life. Maybe you just broke up with someone, and listening to music helps you work through the grief you are experiencing to get to a better place. For others, they need to openly communicate about how they are feeling in an effort to process and work through emotions. The worst thing a person can do is attempt to deny that the emotion exists.

Think of this like a balloon. With each breath of air you blow into the balloon, you are bottling up more and more emotions. Eventually, that balloon will get to a point where it cannot handle any more air in it before it explodes. Humans can be the same way with emotions when we bottle them up inside. The final breath of air in our emotional balloon doesn’t have to be big or intense. However, it can still cause tremendous emotional outpouring that is often very damaging to the person and their interpersonal relationships with others. Other research has demonstrated that handling negative emotions during conflicts within a marriage can lead to faster de-escalations of conflicts and faster conflict mediation between spouses (Bloch et al., 2014).

Emotional Intelligence

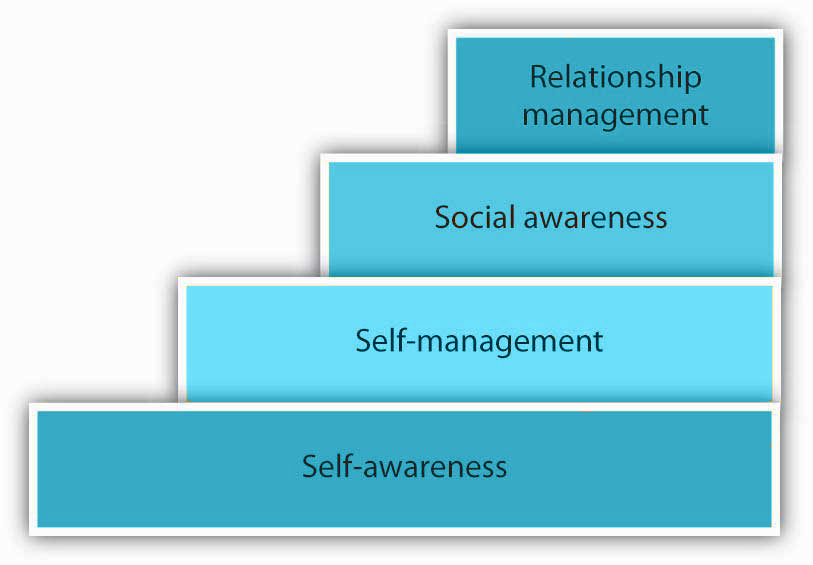

Emotional intelligence(EQ) as an individual’s appraisal and expression of their emotions and the emotions of others in a manner that enhances thought, living, and communicative interactions. EQ is built by four distinct emotional processes: perceiving, understanding, managing, and using emotions (Salovey & Mayer, 2000). All four components of emotional intelligence are important for our ability to manage conflict situations at work.

Let’s discuss the four main components of EQ:

Self-Awareness

Self-awareness refers to a person’s ability to understand their feelings from moment to moment. It might seem as if this is something we know, but we often go about our day without thinking or being aware of our emotions that impact how we behave in work or personal situations. Understanding our emotions can help us reduce stress and make better decisions, especially when we are under pressure. In addition, knowing and recognizing our own strengths and weaknesses is part of self-awareness. Assume that Patt is upset about a new process being implemented in the organization. Lack of self-awareness may result in her feeling angry and anxious, without really knowing why. High self-awareness EQ might cause Patt to recognize that her anger and anxiety stem from the last time the organization changed processes and fifteen people got laid off. Part of self-awareness is the idea of positive psychological capital, which can include emotions such as hope; optimism, which results in higher confidence; and resilience, or the ability to bounce back quickly from challenges (Luthens, 2002). Psychological capital can be gained through self-awareness and self-management, which is our next area of emotional intelligence.

Sadly, many people are just completely unaware of their own emotions. Emotional awareness, or an individual’s ability to clearly express, in words, what they are feeling and why, is an extremely important factor in effective interpersonal communication and conflict management. Unfortunately, our emotional vocabulary is often quite limited. One extreme version of of not having an emotional vocabulary is called alexithymia, “a general deficit in emotional vocabulary—the ability to identify emotional feelings, differentiate emotional states from physical sensations, communicate feelings to others, and process emotion in a meaningful way” (Friedman et al., 2003). Furthermore, there are many people who can accurately differentiate emotional states but lack the actual vocabulary for a wide range of different emotions. For some people, their emotional vocabulary may consist of good, bad, angry, and fine. Learning how to communicate one’s emotions is very important for effective interpersonal relationships (Rosenberg, 2003). First, it’s important to distinguish between our emotional states and how we interpret an emotional state. For example, you can feel sad or depressed, but you really cannot feel alienated. Your sadness and depression may lead you to perceive yourself as alienated, but alienation is a perception of one’s self and not an actual emotional state. There are several evaluative terms that people ascribe themselves (usually in the process of blaming others for their feelings) that they label emotions, but which are in actuality evaluations and not emotions. Table 7.1 presents a list of common evaluative words that people confuse for emotional states.

7.1 Common Evaluative Words Used Confused for Emotional States

| Abandoned | Attacked | Bullied |

| Cornered | Humiliated | Let down |

| Mistreated | Patronized | Putdown |

| Scorned | Tortured | Unsupported |

| Abused | Belittled | Cheated |

| Devalued | Injured | Maligned |

| Misunderstood | Pressured | Rejected |

| Taken for granted | Unappreciated | Unwanted |

| Affronted | Betrayed | Coerced |

| Diminished | Interrupted | Manipulated |

| Neglected | Provoked | Ridiculed |

| Threatened | Unheard | Used |

| Alienated | Boxed-in | Co-opted |

| Distrusted | Intimidated | Mocked |

| Overworked | Put away | Ruined |

| Thwarted | Unseen | Wounded |

Evaluative Words Confused for Emotions

Instead, people need to avoid these evaluative words and learn how to communicate effectively using a wide range of emotions. Tables 7.2 and 7.3 provide a list of both positive and negative feelings that people can express. Go through the list considering the power of each emotion. Do you associate light, medium, or strong emotions with the words provided on these lists? Why? There is no right or wrong way to answer this question. Still, it is important to understand that people can differ in their interpretations of the strength of different emotionally laden words. If you don’t know what a word means, you should look it up and add another word to your list of feelings that you can express to others.

Positive Emotions

7.2 Positive Feelings People Can Express

| Absorbed | Intense | Aroused | Mellow | Concerned |

| Eager | Satisfied | Euphoric | Thrilled | Glad |

| Happy | Amazed | Joyous | Carefree | Peaceful |

| Rapturous | Encouraged | Stimulated | Fascinated | Vibrant |

| Adventurous | Interested | Astonished | Merry | Confident |

| Ebullient | Secure | Excited | Tickled Pink | Gleeful |

| Helpful | Amused | Jubilant | Cheerful | Perky |

| Refreshed | Energetic | Sunny | Free | Warm |

| Affectionate | Intrigued | Blissful | Mirthful | Content |

| Ecstatic | Sensitive | Exhilarated | Touched | Glorious |

| Hopeful | Animated | Keyed-up | Comfortable | Pleasant |

| Relaxed | Engrossed | Surprised | Friendly | Wonderful |

| Aglow | Invigorated | Breathless | Moved | Cool |

| Effervescent | Serene | Expansive | Tranquil | Glowing |

| Inquisitive | Appreciative | Lively | Complacent | Pleased |

| Relieved | Enlivened | Tender | Fulfilled | Zippy |

| Alert | Involved | Buoyant | Optimistic | Curious |

| Elated | Spellbound | Expectant | Trusting | Good-humored |

| Inspired | Ardent | Loving | Composed | Proud |

| Sanguine | Enthusiastic | Thankful | Genial | Dazzled |

| Alive | Jovial | Calm | Overwhelmed | Grateful |

| Enchanted | Splendid | Exultant | Upbeat | Quiet |

| Radiant | Gratified | Delighted |

Negative Emotions

7.3 Negative Feelings People Can Express

| Afraid | Sorry | Mean | Gloomy | Despairing |

| Disgusted | Anxious | Tepid | Numb | Hopeless |

| Impatient | Downhearted | Bitter | Unglued | Rancorous |

| Sensitive | Keyed-up | Fearful | Confused | Weepy |

| Aggravated | Spiritless | Melancholy | Grim | Despondent |

| Disheartened | Apathetic | Terrified | Overwhelmed | Horrified |

| Indifferent | Dull | Blah | Unhappy | Reluctant |

| Shaky | Lazy | Fidgety | Cool | Wistful |

| Agitated | Spiteful | Miserable | Grouchy | Detached |

| Dismayed | Appalled | Ticked off | Panicky | Horrible |

| Intense | Edgy | Blue | Unnerved | Repelled |

| Shameful | Leery | Forlorn | Crabby | Withdrawn |

| Alarmed | Startled | Mopey | Guilty | Disaffected |

| Displeased | Apprehensive | Tired | Passive | Hostile |

| Irate | Embarrassed | Bored | Unsteady | Resentful |

| Shocked | Lethargic | Frightened | Cranky | Woeful |

| Angry | Sullen | Morose | Harried | Disenchanted |

| Disquieted | Aroused | Troubled | Perplexed | Hot |

| Irked | Embittered | Brokenhearted | Upset | Restless |

| Skeptical | Listless | Frustrated | Cross | Worried |

| Anguished | Surprised | Mournful | Heavy | Disappointed |

| Disturbed | Ashamed | Uncomfortable | Pessimistic | Humdrum |

| Irritated | Exasperated | Chagrined | Uptight | Sad |

| Sleepy | Lonely | Furious | Dejected | Wretched |

| Annoyed | Suspicious | Nervous | Helpless | Discouraged |

| Distressed | Beat | Unconcerned | Petulant | Hurt |

| Jealous | Exhausted | Cold | Vexed | Scared |

| Sorrowful | Mad | Galled | Depressed | Sensitive |

| Antagonistic | Tearful | Nettled | Hesitant | Disgruntled |

| Downcast | Bewildered | Uneasy | Puzzled | Ill-Tempered |

| Jittery | Fatigued | Concerned | Weary | Seething |

| Shaky |

Self-Awareness and Anger in Conflict

Anger can also be described as a tip of the iceberg feeling. Just as an iceberg hides most of its bulk below the waterline, anger is a feeling with hidden deeper emotions. If one examines situations (triggers) that cause anger, it is easy to understand that those situations are really causing feelings of hurt, anxiety, shame, frustration, etc. However, it is quicker and less painful to describe them all as anger. Triggers are personal situations that are almost guaranteed to lead to anger. The situations usually refer to behavior directed toward us that is perceived as disrespectful in some way. Lying, stealing, condescending, patronizing, avoiding, and shaming are often mentioned as actions that trigger an anger response. It can be helpful to recognize your own triggers, notice how they feel in your body and assign them a label.

Self-Management

Self-management refers to our ability to manage our emotions and is dependent on our self-awareness ability. How do we handle frustration, anger, and sadness? Are we able to control our behaviors and emotions? Self-management also is the ability to follow through with commitments and take initiative at work. Someone who lacks self-awareness may project stress on others. For example, say that project manager Mae is very stressed about an upcoming Monday deadline. Lack of self-management may cause Mae to lash out at people in the office because of the deadline. Higher EQ in this area might result in Mae being calm, cool, and collected—to motivate her team to focus and finish the project on time.

It is important to understand how bodies display anger. Ask participants to remember a time when they were angry, and let them revisit that feeling. Then ask them how their bodies are telling them that they are angry. A rise in heartbeat and blood pressure, gritting one’s teeth or clenching one’s fists, becoming tense, sweating, grimacing, and feeling a knot in one’s stomach are often mentioned. Body signals are the second clue that you are going to have to do something with your own anger.

What Doesn’t Work: Distorting and Suppressing Negative Affect

Perhaps the most common approach to dealing with negative affect is to attempt to suppress, avoid, or deny it. You probably know people who seem to you to be stressed, depressed, or anxious but who cannot or will not see it in themselves. Perhaps you tried to talk to them about it, to get them to open up to you, but were rebuffed. They seem to act as if there is no problem at all, simply moving on with life without admitting or even trying to deal with the negative feelings. Or perhaps you have taken a similar approach yourself: Have you ever had an important test to study for or an important job interview coming up, and rather than planning and preparing for it, you simply tried put it out of your mind entirely?

Research has found that there are clear difficulties with an approach to negative events and feelings that involves simply trying to ignore them. For one, ignoring our problems does not make them go away. Not being able to get our work done because we are depressed, being too anxious to develop good relationships with others, or experiencing so much stress that we get sick will be detrimental to our life even if we cannot admit that it is occurring.

Suppressing our emotions is also not a very good option, at least in the long run, because it tends to fail (Gross & Levenson, 1997). If we know that we have a big exam coming up, we have to focus on the exam itself in order to suppress it. We can’t really suppress or deny our thoughts because we actually have to recall and face the event in order to make the attempt to not think about it. Furthermore, we may continually worry that our attempts to suppress will fail. Suppressing our emotions might work out for a short while, but when we run out of energy, the negative emotions may shoot back up into consciousness, causing us to re-experience the negative feelings that we had been trying to avoid.

Daniel Wegner and his colleagues (1987) directly tested whether people would be able to effectively suppress a simple thought. They asked participants in a study to not think about a white bear for 5 minutes but to ring a bell in case they did. (Try it yourself—can you do it?) The participants were unable to suppress the thought as instructed—the white bear kept popping into mind, even when they were instructed to avoid thinking about it. You might have had a similar experience when you were staying home to study—the fun time you were missing by staying home kept popping into your mind, disrupting your work.

Another poor approach to attempting to escape from our problems is to engage in behaviors designed to distract us from them. Sometimes this approach will be successful in the short term—we might try distracting ourselves from our troubles by going for a run, watching TV, or reading a book, and perhaps this might be useful. But sometimes people go to extremes to avoid self-awareness when it might be better that they face their troubles directly. If we experience discrepancies between our ideal selves and our important self-concepts, if we feel that we cannot ever live up to our or others’ expectations for us, or if we are just really depressed or anxious, we may attempt to escape ourselves entirely. Roy Baumeister (1991) has speculated that maladaptive behaviors such as drug abuse, sexual masochism, spiritual ecstasy, binge eating, and even suicide are all mechanisms by which people may attempt to escape the self.

A Better Approach: Self-Regulation

As we have seen, emotions are useful in warning us about potential danger and in helping us to make judgments quickly, so it is a good thing that we have them. However, we also need to learn how to control our emotions, to prevent our emotions from letting our behavior get out of control.

To be the best people that we possibly can, we have to work hard at it. Succeeding at school, at work, and at our relationships with others takes a lot of effort. When we are successful at self-regulation, we are able to move toward or meet the goals that we set for ourselves. When we fail at self-regulation, we are not able to meet those goals. People who are better able to regulate their behaviors and emotions are more successful in their personal and social encounters (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992).

Let’s Focus: Self-control

Part of self-management is being able to exert self-control. The ability to exercise self-control has some important positive outcomes. Consider, for instance, research by Walter Mischel and his colleagues (Mischel et al., 1989). In their studies, they had 4- and 5-year-old children sit at a table in front of a yummy snack, such as a chocolate chip cookie or a marshmallow. The children were told that they could eat the snack right away if they wanted to. However, they were also told that if they could wait for just a couple of minutes, they’d be able to have two snacks—both the one in front of them and another just like it. However, if they ate the one that was in front of them before the time was up, they would not get a second.

Part of self-management is being able to exert self-control. The ability to exercise self-control has some important positive outcomes. Consider, for instance, research by Walter Mischel and his colleagues (Mischel et al., 1989). In their studies, they had 4- and 5-year-old children sit at a table in front of a yummy snack, such as a chocolate chip cookie or a marshmallow. The children were told that they could eat the snack right away if they wanted to. However, they were also told that if they could wait for just a couple of minutes, they’d be able to have two snacks—both the one in front of them and another just like it. However, if they ate the one that was in front of them before the time was up, they would not get a second.

Mischel found that some children were able to self-regulate—they were able to override the impulse to seek immediate gratification in order to obtain a greater reward at a later time. Other children, of course, were not—they just ate the first snack right away. Furthermore, the inability to delay gratification seemed to occur in a spontaneous and emotional manner, without much thought. The children who could not resist simply grabbed the cookie because it looked so yummy, without being able to cognitively stop themselves (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999; Strack & Deutsch, 2007). It turns out that these emotional responses are determined in part by particular brain patterns that are influenced by body chemicals. For instance, preferences for small immediate rewards over large later rewards have been linked to low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin in animals (Bizot et al., 1999; Wilkinson & Robbins, 2004), and low levels of serotonin are tied to violence, impulsiveness, and even suicide (Asberg et al., 1976).

The ability to self-regulate in childhood has important consequences later in life. When Mischel followed up on the children in his original study, he found that those who had been able to self-regulate as children grew up to have some highly positive characteristics—they got better SAT scores, were rated by their friends as more socially adept, and were found to cope with frustration and stress better than those children who could not resist the tempting first cookie at a young age. Effective self-regulation is therefore an important key to success in life (Ayduk et al., 2000; Eigsti et al., 2006; Mischel et al., 2003).

Letting Go of Negative Thoughts

Bach and Wyden (1968) discuss gunnysacking (or backpacking) as the imaginary bag we all carry, into which we place unresolved conflicts or grievances over time. If your organization has gone through a merger, and your business has transformed, there may have been conflicts that occurred during the transition. Holding onto the way things used to or to negative emotions related to past conflict be can be like a stone in your gunnysack, and influence how you interpret your current context.

People may be aware of similar issues but might not know your history, and cannot see your backpack or its contents. For example, if your previous manager handled issues in one way, and your new manage handles them in a different way, this may cause you some degree of stress and frustration. Your new manager cannot see how the relationship existed in the past, but will still observe the tension. Bottling up your frustrations only hurts you and can cause your current relationships to suffer. By addressing, or unpacking, the stones you carry, you can better assess the current situation with the current patterns and variables.

We learn from experience, but can distinguish between old wounds and current challenges, and try to focus our energies where they will make the most positive impact. . You may be more successful in raising the issue if you are as specific as possible in describing the problem and how you are affected. If necessary, write your concerns down on paper.

Not only does research show that attempting to suppress our negative thoughts does not work, there is even evidence that the opposite is true—that when we are faced with troubles, it is healthy to let the negative thoughts and feelings out by expressing them, either to ourselves or to others. James Pennebaker and his colleagues (Pennebake et al., 1990; Watson & Pennebaker, 1989) have conducted many correlational and experimental studies that demonstrate the advantages to our mental and physical health of opening up versus bottling our feelings. This research team has found that simply talking about or writing about our emotions or our reactions to negative events provides substantial health benefits.

Pennebaker and Beall (1986) randomly assigned students to write about either the most traumatic and stressful event of their lives or to write about a trivial topic. Although the students who wrote about the traumas had higher blood pressure and more negative moods immediately after they wrote their essays, they were also less likely to visit the student health center for illnesses during the following 6 months in comparison to those who wrote about more minor issues. Something positive evidently occurred as a result of confronting their negative experiences. Other research studied individuals whose spouses had died in the previous year, finding that the more they talked about the death with others, the less likely they were to become ill during the subsequent year. Daily writing about one’s emotional states has also been found to increase immune system functioning (Petrie et al., 2004), and Uysal and Lu (2011) found that self-expression was associated with experiencing less physical pain. Opening up probably helps in various ways. For one, expressing our problems allows us to gain information from others and may also bring support from them. And writing or thinking about one’s experiences also seems to help people make sense of the events and may give them a feeling of control over their lives (Pennebaker & Stone, 2004).

Self-Management in Conflict

It is helpful to repeatedly make the point that one MUST do something with one’s own anger before effectively interacting with other people. It is a truism that, “When anger is high, cognition is low.” Therefore, to be an effective problem solver, it is imperative to deal with one’s own anger before interacting with others. People can often laugh at themselves when they are able to recount instances where they DID deal with other people through the filter of their own anger, and how ineffective the results were. It is irrelevant whether your anger is justified or righteous–it works against your own best interests because it makes you unable to negotiate effectively.

When you notice those first two clues, there are self-calming mechanisms and ways to get rid of the body’s surging adrenaline so that it is again possible to think clearly and problem solve effectively. Counting to ten, taking deep breaths, taking a walk, venting, meditating, and hitting a pillow are some of the strategies that students often report using to calm themselves. These all have a physical reason for being successful–they release chemicals into the brain and body that help rid it of some of the extra adrenaline that makes a person want to either fight or flee. Consider the options in the animal kingdom. When an animal is threatened, its system releases adrenaline. The adrenaline gives the animal the extra energy needed to either flee (if the opponent is bigger or more ferocious), or remain and fight (if the opponent is smaller and/or weaker). These are the only choices that the animal has, and it comes from their instincts in assessing their chances of survival in both scenarios. As human beings, we have a third choice–talking or negotiating. However, to effectively use this third alternative, the adrenaline has to be dispersed so that we can think clearly, which is necessary for negotiation.

Self-regulation is particularly difficult when we are tired, depressed, or anxious, and it is under these conditions that we more easily lose our self-control and fail to live up to our goals (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). If you are tired and worried about an upcoming exam, you may find yourself getting angry and taking it out on your roommate, even though she really hasn’t done anything to deserve it and you don’t really want to be angry at her. It is no secret that we are more likely to fail at our diets when we are under a lot of stress or at night when we are tired.

Can we improve our emotion regulation? It turns out that training —just like physical training—can help. Students who practiced doing difficult tasks, such as exercising, avoiding swearing, or maintaining good posture, were later found to perform better in laboratory tests of self-regulation (Baumeister et al., 2006; Baumeister et al., 2007; Oaten & Cheng, 2006), such as maintaining a diet or completing a puzzle. And we are also stronger when we are in good moods—people who had watched a funny video clip were better at subsequent self-regulation tasks (Tice et al., 2007).

Consider This: Dealing with Anger

Conflicts cannot be effectively resolved if you cannot control your anger. If you are feeling angry:

Conflicts cannot be effectively resolved if you cannot control your anger. If you are feeling angry:

- Take a few deep breaths to calm down

- Say that you are angry and explain why (without becoming abusive)

- Postpone the discussion if you cannot calm yourself

- Write down your key points and concerns before going into another session

- Move your discussion to a neutral location

If the other person is angry, acknowledge their feelings. For example, you might say, “I can see that you were really upset and angry when I said…..” Acknowledging another person’s feelings does not mean that you have to agree with them. It simply says to the person that you recognize what they have said or felt. If the person is unable to regain calm, suggest postponing the discussion.

No matter how healthy and happy we are in our everyday lives, there are going to be times when we experience stress, depression, and anxiety. Some of these experiences will be major and some will be minor, and some of us will experience these emotions more than others. Sometimes these feelings will be the result of clear difficulties that pose direct threats to us: We or those we care about may be ill or injured; we may lose our job or have academic difficulties. At other times, these feelings may seem to develop for no apparent reason.

Although it is not possible to prevent the experience of negative emotions entirely (in fact, given their importance in helping us understand and respond to threats, we would not really want to if we could), we can nevertheless learn to respond to and cope with them in the most productive possible ways. We do not need to throw up our hands in despair when things go wrong—rather, we can bring our personal and social resources to bear to help us. We have at our disposal many techniques that we can use to help us deal with negative emotions.

Social Awareness

Social awareness is our ability to understand social cues that may affect others around us. In other words, understanding how another is feeling, even if we do not feel the same way. Social awareness also includes having empathy for another, recognizing power structure and unwritten workplace dynamics. Most people high on social awareness have charisma and make people feel good with every interaction. For example, consider Erik’s behavior in meetings. He continually talks and does not pick up subtleties, such as body language. Because of this, he can’t understand (or even fathom) that his monologues can be frustrating to others. Erik, with higher EQ in social awareness, may begin talking but also spend a lot of time listening and observing in the meeting, to get a sense of how others feel. He may also directly ask people how they feel. This demonstrates high social awareness.

Communicating Emotion

In addition to experiencing emotions internally, we also express our emotions to others, and we learn about the emotions of others by observing them. This communication process has evolved over time and is highly adaptive. One way that we perceive the emotions of others is through their nonverbal communication, that is, communication, primarily of liking or disliking, that does not involve words (Ambady & Weisbuch, 2010; Andersen, 2007).

The most important communicator of emotion is the face. The face contains 43 different muscles that allow it to make more than 10,000 unique configurations and to express a wide variety of emotions. For example, happiness is expressed by smiles, which are created by two of the major muscles surrounding the mouth and the eyes, and anger is created by lowered brows and firmly pressed lips. Nonverbal communication includes our tone of voice, gait, posture, touch, and facial expressions, and we can often accurately detect the emotions that other people are experiencing through these channels. Table 7. 1, shows some of the important nonverbal behaviours that we use to express emotion and some other information (particularly liking or disliking, and dominance or submission).

Table 7.4 Some Common Nonverbal Communicators

| Nonverbal cue | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Proxemics | Rules about the appropriate use of personal space | Standing nearer to someone can express liking or dominance. |

| Body appearance | Expressions based on alterations to our body | Body building, breast augmentation, weight loss, piercings, and tattoos are often used to appear more attractive to others. |

| Body positioning and movement | Expressions based on how our body appears | A more open body position can denote liking; a faster walking speed can communicate dominance. |

| Gestures | Behaviours and signs made with our hands or faces | The peace sign communicates liking; the finger communicates disrespect. |

| Facial expressions | The variety of emotions that we express, or attempt to hide, through our face | Smiling or frowning and staring or avoiding looking at the other can express liking or disliking, as well as dominance or submission. |

| Paralanguage | Clues to identity or emotions contained in our voices | Pronunciation, accents, and dialect can be used to communicate identity and liking. |

| Source: Introduction to Psychology - 1st Canadian Edition by Jennifer Walinga and Charles Stangor, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | ||

Just as there is no universal spoken language, there is no universal nonverbal language. For instance, in Canada we express disrespect by showing the middle finger (the finger or the bird). But in Britain, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand, the V sign (made with back of the hand facing the recipient) serves a similar purpose. In countries where Spanish, Portuguese, or French are spoken, a gesture in which a fist is raised and the arm is slapped on the bicep is equivalent to the finger, and in Russia, Indonesia, Turkey, and China a sign in which the hand and fingers are curled and the thumb is thrust between the middle and index fingers is used for the same purpose.

Culture and Displaying Emotions

Culture can impact the way in which people understand and display emotion. A cultural display rule is one of a collection of culturally specific standards that govern the types and frequencies of displays of emotions that are acceptable (Malatesta & Haviland, 1982). Therefore, people from varying cultural backgrounds can have very different cultural display rules of emotion. For example, research has shown that individuals from the United States express negative emotions like fear, anger, and disgust both alone and in the presence of others, while Japanese individuals only do so while alone (Matsumoto, 1990). Furthermore, individuals from cultures that tend to emphasize social cohesion are more likely to engage in suppression of emotional reaction so they can evaluate which response is most appropriate in a given context (Matsumoto et al., 2008).

Research by Paul Ekman (1972) demonstrates that despite different emotional display rules, our ability to recognize and produce facial expressions of emotion appears to be universal. In fact, even congenitally blind individuals produce the same facial expression of emotions, despite their never having the opportunity to observe these facial displays of emotion in other people. This would seem to suggest that the pattern of activity in facial muscles involved in generating emotional expressions is universal, and indeed, this idea was suggested in the late 19th century in Charles Darwin’s book The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). There is substantial evidence for seven universal emotions that are each associated with distinct facial expressions for happiness, surprise, sadness, fright, disgust, contempt, and anger. (Ekman & Keltner, 1997).

Of course, emotion is not only displayed through facial expression. We also use the tone of our voices, various behaviors, and body language to communicate information about our emotional states. Body language is the expression of emotion in terms of body position or movement. Research suggests that we are quite sensitive to the emotional information communicated through body language, even if we’re not consciously aware of it (de Gelder, 2006; Tamietto et al., 2009).

Relationship Management

Relationship management refers to our ability to communicate clearly, maintain good relationships with others, work well in teams, and manage conflict. Relationship management relies on your ability to use the other three areas of EQ to manage relationships effectively. Take Caroline, for example. Caroline is good at reading people’s emotions and showing empathy for them, even if she doesn’t agree. As a manager, her door is always open and she makes it clear to colleagues and staff that they are welcome to speak with her anytime. If Caroline has low EQ in the area of relationship management, she may belittle people and have a difficult time being positive. She may not be what is considered a good team player, which shows her lack of ability to manage relationships.

Finding Satisfaction Through Our Connections With Others

Well-being is determined in part by genetic factors, such that some people are naturally happier than others (Braungart et al., 1992; Lykken, 2000), but also in part by the situations that we create for ourselves. Psychologists have studied hundreds of variables that influence happiness, but there is one that is by far the most important, and it is one that is particularly social psychological in nature: People who report that they have positive social relationships with others—the perception of social support—also report being happier than those who report having less social support (Diener et al., 1999; Diener et al., 2006). Married people report being happier than unmarried people (Pew, 2006), and people who are connected with and accepted by others suffer less depression, higher self-esteem, and less social anxiety and jealousy than those who feel more isolated and rejected (Leary, 1990).

Social support also helps us better cope with stressors. Koopman et al. (1998) found that women who reported higher social support experienced less depression when adjusting to a diagnosis of cancer, and Ashton et al. (2005) found a similar buffering effect of social support for AIDS patients. People with social support are less depressed overall, recover faster from negative events, and are less likely to commit suicide (Au, Lau, & Lee, 2009; Bertera, 2007; Compton et al., 2005; Skärsäter et al., 2005).

Relationship Management in Conflict

Research repeatedly demonstrates that how emotion is communicated will affect the outcome of the communication situation. Relationship partners are more satisfied when positive emotions are communicated rather than negative emotions. Four forms of anger expression have been identified (Guerrero, 1994). The four forms of anger expression range from direct and nonthreatening to avoidance and denial of angry feelings. Anger expression is more productive when the emotion is communicated directly and in a nonthreatening manner. In most circumstances, direct communication is more constructive.

Table 7.5 Forms of Anger Expression

| Form of Expression | Explanation of Form |

|---|---|

| Assertion | Direct statements, nonthreatening, explaining anger |

| Aggression | Direct and threatening, may involve criticism |

| Passive Aggression | Indirectly communicate negative affect in a destructive manner the silent treatment |

| Avoidance | Avoiding the issue, denying angry feelings, pretending not to feel anything |

| Source: Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | |

Furthermore, researchers have found that serious relationship problems arise when those in the relationship are unable to reach beyond the immediate conflict and include positive as well as negative emotions in their discussions. In a landmark study of newlywed couples, for example, researchers attempted to predict who would have a happy marriage versus an unhappy marriage or a divorce, based on how the newlyweds communicated with each other. Specifically, they created a stressful conflict situation for couples. The researchers then evaluated how many times the newlyweds expressed positive emotions and how many times they expressed negative emotions in talking with each other about the situation.

When the marital status and happiness of each couple were evaluated over the next six years, the study found that the strongest predictor of a marriage that stayed together and was happy was the degree of positive emotions expressed during the conflict situation in the initial interview (Gottman et al., 1998).

In happy marriages, instead of always responding to anger with anger, the couples found a way to lighten the tension and to de-escalate the conflict. In long-lasting marriages, during stressful times or in the middle of conflict, couples were able to interject some positive comments and positive regard for each other. When this finding is generalized to other types of interpersonal relationships, it makes a strong case for having some positive interactions, interjecting some humor, some light-hearted fun, or some playfulness into your conversation while you are trying to resolve conflict

Consider This: Defusing Other People’s Anger

This is a five-step developmental model for diffusing anger, which means that in order to be effective, one needs to begin at step one, and then go to step two, step three, step four, and step five, in that sequence. There is a temptation to cut to the chase and go directly to step five. However, when someone is angry, they are not ready to discuss an issue rationally. Therefore, the first four steps focus on defusing the anger, and it is only when we reach the fifth step that we can open the door to problem solving. Sometimes, the anger can be dissipated in one, two, or three steps, and in that case, it is possible to move to problem solving. However, it is the angry person who decides (when they are able to let go of their anger) when it is possible to move on to problem solving. The first step is to listen–which means paying attention to both the words and the feelings behind what your conflict partner is expressing. Many people interrupt the speaker (which re-escalates anger) because they are afraid that the person will vent forever. In reality, that does not happen. People stop venting if they believe you are listening because they want a reaction from you. If you do not interrupt, they will stop talking to get that reaction. Our perception of the passage of time is skewed in these kinds of scenario. Two minutes of an angry diatribe can seem like an eternity.

This is a five-step developmental model for diffusing anger, which means that in order to be effective, one needs to begin at step one, and then go to step two, step three, step four, and step five, in that sequence. There is a temptation to cut to the chase and go directly to step five. However, when someone is angry, they are not ready to discuss an issue rationally. Therefore, the first four steps focus on defusing the anger, and it is only when we reach the fifth step that we can open the door to problem solving. Sometimes, the anger can be dissipated in one, two, or three steps, and in that case, it is possible to move to problem solving. However, it is the angry person who decides (when they are able to let go of their anger) when it is possible to move on to problem solving. The first step is to listen–which means paying attention to both the words and the feelings behind what your conflict partner is expressing. Many people interrupt the speaker (which re-escalates anger) because they are afraid that the person will vent forever. In reality, that does not happen. People stop venting if they believe you are listening because they want a reaction from you. If you do not interrupt, they will stop talking to get that reaction. Our perception of the passage of time is skewed in these kinds of scenario. Two minutes of an angry diatribe can seem like an eternity.

The second step is to acknowledge the anger. This means making a process observation about what you see (i.e., I can see that you are really upset) without any judgment attached. It is also important to stop after each step and allow time for processing. If you rush ahead to explain away the anger, the other person will not feel acknowledged.

The third step is to apologize. In our society this is often difficult for people because we feel that apology is synonymous with taking responsibility. Therefore, if something was not my fault, how can I take responsibility for it? However, what you are really saying is that you are sorry for the other person’s pain (as when you pay a condolence call and tell someone you are sorry about the death–you do not believe that you caused it, but you are focusing on the feelings of the person in front of you). It is possible to be genuinely sorry for someone’s pain without taking responsibility for causing the pain.

The fourth step is to agree with the truth. Again, this is difficult for people who are reluctant to own part of the problem (especially if you think the person is unreasonably angry). However, if everyone is right from their own perspective (which is what non-violent conflict resolution theory believes), then you are not saying their perspective is the only one, but that it is a legitimate perspective. Statements such as “If I were in your position, I’d be angry too” can help de-escalate the situation so that problem solving may occur. These statements have to be real, rather than platitudes. This process can be both time and energy consuming. However, if this process is not used, and the other person stays angry, effective problem solving cannot occur.

Finally, if the other person has calmed down somewhat they will be open when you invite criticism. This means involving the other person in a discussion of how the situation could have been handled differently. This is useful information for you, so that in the future, either in similar situations, or with this specific person, more options are available to you. Although this process may seem long, it is one that respects the feelings of the other person, and gives him or her the opportunity to regain his or her cognitive abilities by reducing anger. This process also engages the other person as an ally and refrains from blame or accusation.

Self-assessment

See Appendix B: Self-Assessments

Read the following questions and select the answer that corresponds with your perception.:

Figure 7.3 Long Description

| Level of Arousal | Unpleasant | Pleasant |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | Miserable, Sad, Depressed, Gloomy, Bored, Droopy | Content, Satisfied, At ease, Serene, Calm, Relaxed, Sleepy, Tired |

| Intense | Alarmed, Afraid, Angry, Intense, Annoyed, Frustrated, Distressed | Astonished, Excited, Amused, Happy, Delighted, Glad, Pleased |

Adapted Works

“Conflict in Relationships” in Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Moods and Emotions in Our Social Lives” in Principles of Social Psychology by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“The Experience of Emotion” in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition by Sally Walters which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Your Brain on Conflict” in Making Conflict Suck Less: The Basics by Ashley Orme Nichols is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Emotions and Motivations” in Introduction to Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition by Jennifer Walinga and Charles Stangor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication” in Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Emotion” in Psychology 2e by Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett, et al. and OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

Ayduk, O., Mendoza-Denton, R., Mischel, W., Downey, G., Peake, P. K., & Rodriguez, M. (2000). Regulating the interpersonal self: Strategic self-regulation for coping with rejection sensitivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 776–792.

Bach, G., & Wyden, P. (1968). The intimacy enemy. Avon.

Baumeister, R. F. (1991). The self against itself: Escape or defeat? In Relational self: Theoretical convergences in psychoanalysis and social psychology (pp. 238–256). Guilford Press.

Baumeister, R. F., Gailliot, M., DeWall, C. N., & Oaten, M. (2006). Self-regulation and personality: How interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. Journal of Personality, 74, 1773–1801.

Baumeister, R. F., Schmeichel, B., & Vohs, K. D. (2007). Self-regulation and the executive function: The self as controlling agent. In A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (Vol. 2). Guilford.

Bertera, E. (2007). The role of positive and negative social exchanges between adolescents, their peers and family as predictors of suicide ideation. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 24(6), 523–538. doi:10.1007/s10560-007-0104-y

Bizot, J.-C., Le Bihan, C., Peuch, A. J., Hamon, M., & Thiebot, M.-H. (1999). Serotonin and tolerance to delay of reward in rats. Psychopharmacology, 146(4), 400–412.

Bloch, L., Haase, C. M., & Levenson, R. W. (2014). Emotion regulation predicts marital satisfaction: More than a wives’ tale. Emotion, 14(1), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034272

Braungart, J. M., Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., & Fulker, D. W. (1992). Genetic influence on tester-rated infant temperament as assessed by Bayley’s Infant Behavior Record: Nonadoptive and adoptive siblings and twins. Developmental Psychology, 28(1), 40–47.

Compton, M., Thompson, N., & Kaslow, N. (2005). Social environment factors associated with suicide attempt among low-income African Americans: The protective role of family relationships and social support. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(3), 175–185. doi:10.1007/ s00127-005-0865-6

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Diener, E., Tamir, M., & Scollon, C. N. (2006). Happiness, life satisfaction, and fulfillment: The social psychology of subjective well-being. In P. A. M. VanLange (Ed.), Bridging social psychology: Benefits of transdisciplinary approaches. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eigsti, I.-M., Zayas, V., Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., Ayduk, O., Dadlani, M. B., et al. (2006). Predicting cognitive control from preschool to late adolescence and young adulthood. Psychological Science, 17(6), 478–484.

Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1992). Emotion, regulation, and the development of social competence. In Emotion and social behavior (pp. 119–150). Sage Publications.

Friedman, S. R., Rapport, L. J., Lumley, M., Tzelepis, A., VanVoorhis, A., Stettner, L., & Kakaati, L. (2003). Aspects of social and emotional competence in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology, 17(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.17.1.50

Gottman, J. M., Coan, J., Carrere, S. & Swanson, C. (1998). Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 60(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/353438

Gross, J. J., & Levenson, R. W. (1997). Hiding feelings: The acute effects of inhibiting negative and positive emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(1), 95–103.

Guerrero, L. K. (1994). ‘‘I’m so mad I could scream:’’ The effects of anger expression on relational satisfaction and communication competence. Southern Communication Journal, 59(2), 125-141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949409372931

Koopman, C., Hermanson, K., Diamond, S., Angell, K., & Spiegel, D. (1998). Social support, life stress, pain and emotional adjustment to advanced breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 7(2), 101–110.

Leary, M. R. (1990). Responses to social exclusion: Social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(2), 221–229.

Lykken, D. T. (2000). Happiness: The nature and nurture of joy and contentment. St. Martin’s Press.

Metcalfe, J., & Mischel, W. (1999). A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychological Review, 106(1), 3–19.

Mischel, W., Ayduk, O., & Mendoza-Denton, R. (Eds.). (2003). Sustaining delay of gratification over time: A hot-cool systems perspective. Russell Sage Foundation.

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. L. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244, 933–938.

Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126, 247–259.

Oaten, M., & Cheng, K. (2006). Longitudinal gains in self-regulation from regular physical exercise. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 717–733.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Beall, S. K. (1986). Confronting a traumatic event: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(3), 274–281.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Stone, L. D. (Eds.). (2004). Translating traumatic experiences into language: Implications for child abuse and long-term health. American Psychological Association.

Pennebaker, J. W., Colder, M., & Sharp, L. K. (1990). Accelerating the coping process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(3), 528–537.

Peterson, C., Seligman, M. E. P., Yurko, K. H., Martin, L. R., & Friedman, H. S. (1998). Catastrophizing and untimely death. Psychological Science, 9(2), 127–130.

Petrie, K. J., Fontanilla, I., Thomas, M. G., Booth, R. J., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2004). Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: A randomized trial. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(2), 272–275.

Pew Research Center (2006, February 13). Are we happy yet? http://pewresearch.org/pubs/301/are-we-happy-yet

Rosenberg, M. B. (2003). Nonviolent communication: A language of life (2nd ed.). Puddle Dancer Press.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 9, 185-211.

Skärsäter, I., Langius, A., Ågren, H., Häggström, L., & Dencker, K. (2005). Sense of coherence and social support in relation to recovery in first-episode patients with major depression: A one-year prospective study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 14(4), 258–264. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00390.

Strack, F., & Deutsch, R. (2007). The role of impulse in social behavior. In A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (Vol. 2). Guilford.

Tice, D. M., Baumeister, R. F., Shmueli, D., & Muraven, M. (2007). Restoring the self: Positive affect helps improve self-regulation following ego depletion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(3), 379–384.

Uysal, A., & Lu, Q. (2011, July 4). Is self-concealment associated with acute and chronic pain? Health Psychology, 30(5), 606–614. doi:10.1037/a0024287

Watson, D., & Pennebaker, J. W. (1989). Health complaints, stress, and distress: Exploring the central role of negative affectivity. Psychological Review, 96(2), 234–254.

Wegner, D. M., Schneider, D. J., Carter, S. R., & White, T. L. (1987). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(1), 5–13.