5.3 Collaboration, Decision-Making and Problem Solving in Groups

In this section:

Cooperation and Collaboration

When it comes to how groups work, they can be cooperative, collaborative, or a combination of both. What is the difference between cooperation and collaboration? The two terms are often used interchangeably but the distinction between them can be important. In The Construction of Shared Knowledge in Collaborative Problem Solving, Roschelle and Teasley define cooperative group work as “the division of labour among participants, as an activity where each person is responsible for a portion of the problem solving” and collaborative work is “a coordinated, synchronous activity that is the result of a continued attempt to construct and maintain a shared conception of a problem” (1995, p. 70). In many classes, students will cooperate on an assignment and one person will work on the visual aid, another will do the research, and someone else will do the writing.

If a group works collaboratively, everyone shares ideas and contributes to all aspects of the project. The advantage of this is that everyone can have input, have a chance to point out weaknesses, and make the end result better. The disadvantages of this are that it can take more time because the group has to make decisions together which can be chaotic and lead to interpersonal conflicts. This can be minimized by following the guidelines on how to deal with conflict in this textbook. In reality, most groups do a combination of cooperation and collaboration but in most cases, groups should try to be as collaborative as possible.

Lynn Power (2016) puts it well when she writes:

The reality is that true collaboration is hard — and it doesn’t mean compromise or consensus-building. It means giving up control to other people. It means being vulnerable. It means needing to know when to fall on your sword and when to back down. Collaboration is inherently messy. Great ideas need some tension; otherwise, they would be easy to make. And ultimately, members need to be respectful of other people’s roles, thoughts and what they bring to the table. And there also needs to be trusted.

Problem Solving and Decision-Making in Groups and Teams

No matter who you are or where you live, problems are an inevitable part of life. This is true for groups as much as for individuals. Some especially work teams are formed specifically to solve problems. Other groups encounter problems for a wide variety of reasons. A problem might be important to the success of the operation, such as increasing sales or minimizing burnout, or it could be dysfunctional group dynamics such as some team members contributing more effort than others yet achieving worse results. Whatever the problem, having the resources of a group can be an advantage as different people can contribute different ideas for how to reach a satisfactory solution.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Groups when Solving Problems and Making Decisions

Groups can make higher quality decisions and come up with more creative solutions to problems compared to individuals making decisions alone.

However, it is important to recognize that group decision-making is not without challenges. Some groups get bogged down by conflict, while others go to the opposite extreme and push for agreement at the expense of quality discussions. Groupthink occurs when group members choose not to voice their concerns or objections because they would rather keep the peace and not annoy or antagonize others. Sometimes groupthink occurs because the group has a positive team spirit and camaraderie, and individual group members don’t want that to change by introducing conflict. It can also occur because past successes have made the team complacent.

Often, one individual in the group has more power or exerts more influence than others and discourages those with differing opinions from speaking up (suppression of dissent) to ensure that only their own ideas are implemented. If members of the group are not really contributing their ideas and perspectives, however, then the group is not getting the benefits of group decision-making.

Characteristics of the Problem

When a group approaches a new problem, it is important to consider contextual factors as well as the characteristics of the group and the problem itself. When it comes to the nature of the problem, five common and important characteristics to consider are task difficulty, number of possible solutions, group member interest in problem, group member familiarity with problem, and the need for solution acceptance (Adams & Galanes, 2009).

- Task difficulty. Difficult tasks are also typically more complex. Groups should be prepared to spend time researching and discussing a difficult and complex task in order to develop a shared foundational knowledge. This typically requires individual work outside of the group and frequent group meetings to share information.

- Number of possible solutions. There are usually multiple ways to solve a problem or complete a task, but some problems have more potential solutions than others or may be creatively based.

- Group member interest in problem. When group members are interested in the problem, they will be more engaged with the problem-solving process and invested in finding a quality solution. Groups with high interest in and knowledge about the problem may want more freedom to develop and implement solutions, while groups with low interest may prefer a leader who provides structure and direction.

- Group familiarity with problem. Some groups encounter a problem regularly, while other problems are more unique or unexpected. Many groups that rely on funding have to revisit a budget every year, and in recent years, groups have had to get more creative with budgets as funding has been cut in nearly every sector. When group members aren’t familiar with a problem, they will need to do background research on what similar groups have done and may also need to bring in outside experts.

- Need for solution acceptance.I n this step, groups must consider how many people the decision will affect and how much “buy-in” from others the group needs in order for their solution to be successfully implemented. Some small groups have many stakeholders on whom the success of a solution depends. Other groups are answerable only to themselves. When a small group is planning on implementing a new policy in a large business, it can be very difficult to develop solutions that will be accepted by all. In such cases, groups will want to poll those who will be affected by the solution and may want to do a pilot implementation to see how people react. Imposing an excellent solution that doesn’t have buy-in from stakeholders can still lead to failure.

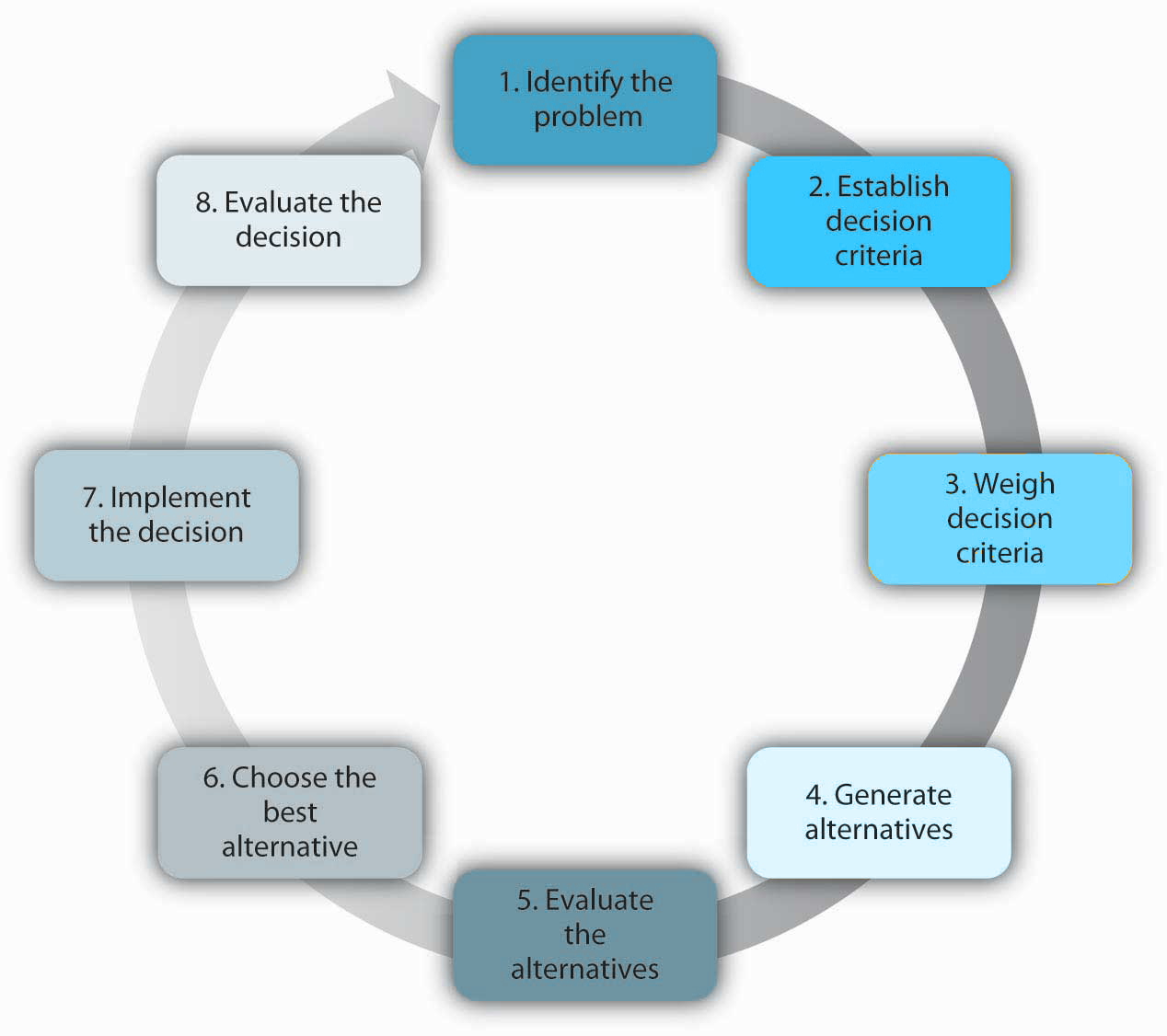

Steps in the Rational Decision-Making Process

Once a group encounters a problem, questions that come up range from “Where do we start?” to “How do we solve it?” While there are many approaches to a problem, the steps in the rational decision-making model are a good start.

Group Decision-Making Techniques

Some decision-making techniques involve determining a course of action based on the level of agreement among the group members. In the rational decision-making model, this is represented in Stage 6 – choosing the best alternative. Common ways to reach make this decision include majority, expert, authority, and consensus rule.

Majority Rule

Majority rule is a commonly used decision-making technique in which a majority (one-half plus one) must agree before a decision is made. A show-of-hands vote, a paper ballot, or an electronic voting system can determine the majority choice.. Of course, other individuals and mediated messages can influence a person’s vote, but since the voting power is spread out over all group members, it is not easy for one person or party to take control of the decision-making process.

Minority Rule

Minority rule is a decision-making technique in which a designated authority or expert has final say over a decision and may or may not consider the input of other group members. When a designated expert makes a decision by minority rule, there may be buy-in from others in the group, especially if the members of the group didn’t have relevant knowledge or expertise. When a designated authority makes decisions, buy-in will vary based on group members’ level of respect for the authority. For example, decisions made by an elected authority may be more accepted by those who elected them than by those who didn’t. As with majority rule, this technique can be time saving. Unlike majority rule, one person or party can have control over the decision-making process. This type of decision making is more similar to that used by monarchs and dictators. An obvious negative consequence of this method is that the needs or wants of one person can override the needs and wants of the majority. A minority deciding for the majority has led to negative consequences throughout history. The quality of the decision and its fairness really depends on the designated expert or authority.

Consensus Rule

Consensus rule is a decision-making technique in which all members of the group must agree on the same decision. On rare occasions, a decision may be ideal for all group members, which can lead to unanimous agreement without further debate and discussion. Although this can be positive, be cautious that this isn’t a sign of groupthink. More typically, consensus is reached only after lengthy discussion. On the plus side, consensus often leads to high-quality decisions due to the time and effort it takes to get everyone in agreement. Group members are also more likely to be committed to the decision because of their investment in reaching it. On the negative side, the ultimate decision is often one that all group members can live with but not one that’s ideal for all members. Additionally, the process of arriving at consensus also includes conflict, as people debate ideas and negotiate the interpersonal tensions that may result.

Commonly used methods of decision making such as majority vote can help or hurt conflict management efforts. While an up-and-down vote can allow a group to finalize a decision and move on, members whose vote fell on the minority side may feel resentment toward other group members. This can create a win/lose climate that leads to further conflict. Having a leader who makes ultimate decisions can also help move a group toward completion of a task, but conflict may only be pushed to the side and left not fully addressed. Third-party mediation can help move a group past a conflict and may create less feelings of animosity, since the person mediating and perhaps making a decision isn’t a member of the group. In some cases, the leader can act as an internal third-party mediator to help other group members work productively through their conflict. The pros and cons of each of these decision-making techniques are summarized in Table 5.3 below.

Table 5.3 Pros and Cons of Agreement-Based Decision-Making Techniques

| Decision-Making Technique | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Majority rule | Quick | Close decisions (5/4) may reduce internal and external buy-in |

| Efficient in large groups | Doesn't take advantage of group synergy to develop alternatives that more members can support | |

| Each vote counts equally | Minority may feel alienated | |

| Minority rule by expert | Quick | Expertise must be verified |

| Decision quality is better than what less knowledgeable people could produce | Experts can be difficult to find / pay for | |

| Experts are typically objective and less easy to influence | Group members may feel useless | |

| Minority rule by authority | Quick | Authority may not be seen as legitimate, leading to less buy-in |

| Buy-in could be high if authority is respected | Group members may try to sway the authority or compete for his or her attention | |

| Unethical authorities could make decisions that benefit them and harm group members | ||

| Consensus rule | High-quality decisions due to time invested | Time consuming |

| Higher level of commitment because of participation in decision | Difficult to manage idea and personal conflict that can emerge as ideas are debated | |

| Satisfaction with decision because of shared agreement | Decision may be OK but not ideal | |

| Source: Communication in the Real World by University of Minnesot, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | ||

Let’s Focus: The Nominal Group Technique

Discussion before Decision Making

Discussion before Decision Making

The nominal group technique guides decision making through a four-step process that includes idea generation and evaluation and seeks to elicit equal contributions from all group members (Delbecq & Ven de Ven, 1971). This method is useful because the procedure involves all group members systematically, which fixes the problem of uneven participation during discussions. Since everyone contributes to the discussion, this method can also help reduce instances of social loafing. To use the nominal group technique, do the following:

- Silently and individually list ideas.

- Create a master list of ideas.

- Clarify ideas as needed.

- Take a secret vote to rank group members’ acceptance of ideas.

During the first step, have group members work quietly, in the same space, to write down every idea they have to address the task or problem they face. This shouldn’t take more than twenty minutes. Whoever is facilitating the discussion should remind group members to use brainstorming techniques, which means they shouldn’t evaluate ideas as they are generated. Ask group members to remain silent once they’ve finished their list so they do not distract others.

During the second step, the facilitator goes around the group in a consistent order asking each person to share one idea at a time. As the idea is shared, the facilitator records it on a master list that everyone can see. Keep track of how many times each idea comes up, as that could be an idea that warrants more discussion. Continue this process until all the ideas have been shared. As a note to facilitators, some group members may begin to edit their list or self-censor when asked to provide one of their ideas. To limit a person’s apprehension with sharing his or her ideas and to ensure that each idea is shared, I have asked group members to exchange lists with someone else so they can share ideas from the list they receive without fear of being personally judged.

During step three, the facilitator should note that group members can now ask for clarification on ideas on the master list. Do not let this discussion stray into evaluation of ideas. To help avoid an unnecessarily long discussion, it may be useful to go from one person to the next to ask which ideas need clarifying and then go to the originator(s) of the idea in question for clarification.

During the fourth step, members use a voting ballot to rank the acceptability of the ideas on the master list. If the list is long, you may ask group members to rank only their top five or so choices. The facilitator then takes up the secret ballots and reviews them in a random order, noting the rankings of each idea. Ideally, the highest ranked idea can then be discussed and decided on. The nominal group technique does not carry a group all the way through to the point of decision; rather, it sets the group up for a roundtable discussion or use of some other method to evaluate the merits of the top ideas.

Improving the Quality of Group Decisions

An advantage to involving groups in decision-making is that you can incorporate different perspectives and ideas. For this advantage to be realized, however, you need a diverse group. In a diverse group, the different group members will each tend to have different preferences, opinions, biases, and stereotypes. Because a variety of viewpoints must be negotiated and worked through, group decision-making creates additional work for a manager, but (provided the group members reflect different perspectives) it also tends to reduce the effects of bias on the outcome. For example, a hiring committee made up of all men might end up hiring a larger proportion of male applicants (simply because they tend to prefer people who are more similar to themselves). But with a hiring committee made up of an equal number of men and women, the bias should be cancelled out, resulting in more applicants being hired based on their qualifications rather than their physical attributes.

Having more people involved in decision-making is also beneficial because each individual brings unique information or knowledge to the group, as well as different perspectives on the problem. Additionally, having the participation of multiple people will often lead to more options being generated and to greater intellectual stimulation as group members discuss the available options. Brainstorming is a process of generating as many solutions or options as possible and is a popular technique associated with group decision-making.

All of these factors can lead to superior outcomes when groups are involved in decision-making. Furthermore, involving people who will be affected by a decision in the decision-making process will allow those individuals to have a greater understanding of the issues or problems and a greater commitment to the solutions.

Effective managers will try to ensure quality group decision-making by forming groups with diverse members so that a variety of perspectives will contribute to the process. They will also encourage everyone to speak up and voice their opinions and thoughts prior to the group reaching a decision. Sometimes groups will also assign a member to play the devil’s advocate in order to reduce groupthink. The devil’s advocate intentionally takes on the role of critic. Their job is to point out flawed logic, to challenge the group’s evaluations of various alternatives, and to identify weaknesses in proposed solutions. This pushes the other group members to think more deeply about the advantages and disadvantages of proposed solutions before reaching a decision and implementing it.

The methods we’ve just described can all help ensure that groups reach good decisions, but what can a manager do when there is too much conflict within a group? In this situation, managers need to help group members reduce conflict by finding some common ground—areas in which they can agree, such as common interests, values, beliefs, experiences, or goals. Keeping a group focused on a common goal can be a very worthwhile tactic to keep group members working with rather than against one another. Table 5.4 summarizes the techniques to improve group decision-making.

Table 5.4 Summary of Techniques That May Improve Group Decision-Making

| Type of Decision | Technique | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Group decisions | Have diverse members in the group. | Improves quality: generates more options, reduces bias |

| Assign a devils advocate. | Improves quality: reduces groupthink | |

| Encourage everyone to speak up and contribute. | Improves quality: generates more options, prevents suppression of dissent | |

| Help group members find common ground. | Improves quality: reduces personality conflict | |

| Source: Organizational Behavior, Rice University, CC-BY 4.0. | ||

Case Study

Adapted Works

“Group Decision-Making” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

“Group Problem Solving” in Business Communication for Success by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Small Group Dynamics” and “Leadership, Roles, and Problem Solving in Groups” in Communication in the Real World by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Small Group Communication” in Introduction to Communication (2nd edition), Indiana State University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

Adams, K., & Galanes, G. G. (2009). Communicating in groups: Applications and skills (7th ed). McGraw-Hill.

Delbecq, A. L., & Ven de Ven, A. H. (1971). A group process model for problem identification and program planning. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 7(4), 466–92.

Power, L. (2016, June 6). Collaboration vs. cooperation: There is a difference. Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lynn-power/collaboration-vs-cooperat_b_10324418.html

Roschelle, J. & Teasley, S.D. (1995). The construction of shared knowledge in collaborative problem solving. http://tecfa.unige.ch/tecfa/publicat/dil-papers-2/cscl.pdf

Roschelle, J., & Teasley, S. D. (1995). The construction of shared Knowledge in collaborative problem solving. In C. O’Malley (Ed.). Computer Supported Collaborative Learning. NATO ASI Series, 128, 67-97. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-85098-1_5