3.2 Creating, Maintaining, and Changing Culture

In this section:

Creating and Maintaining Organizational Culture

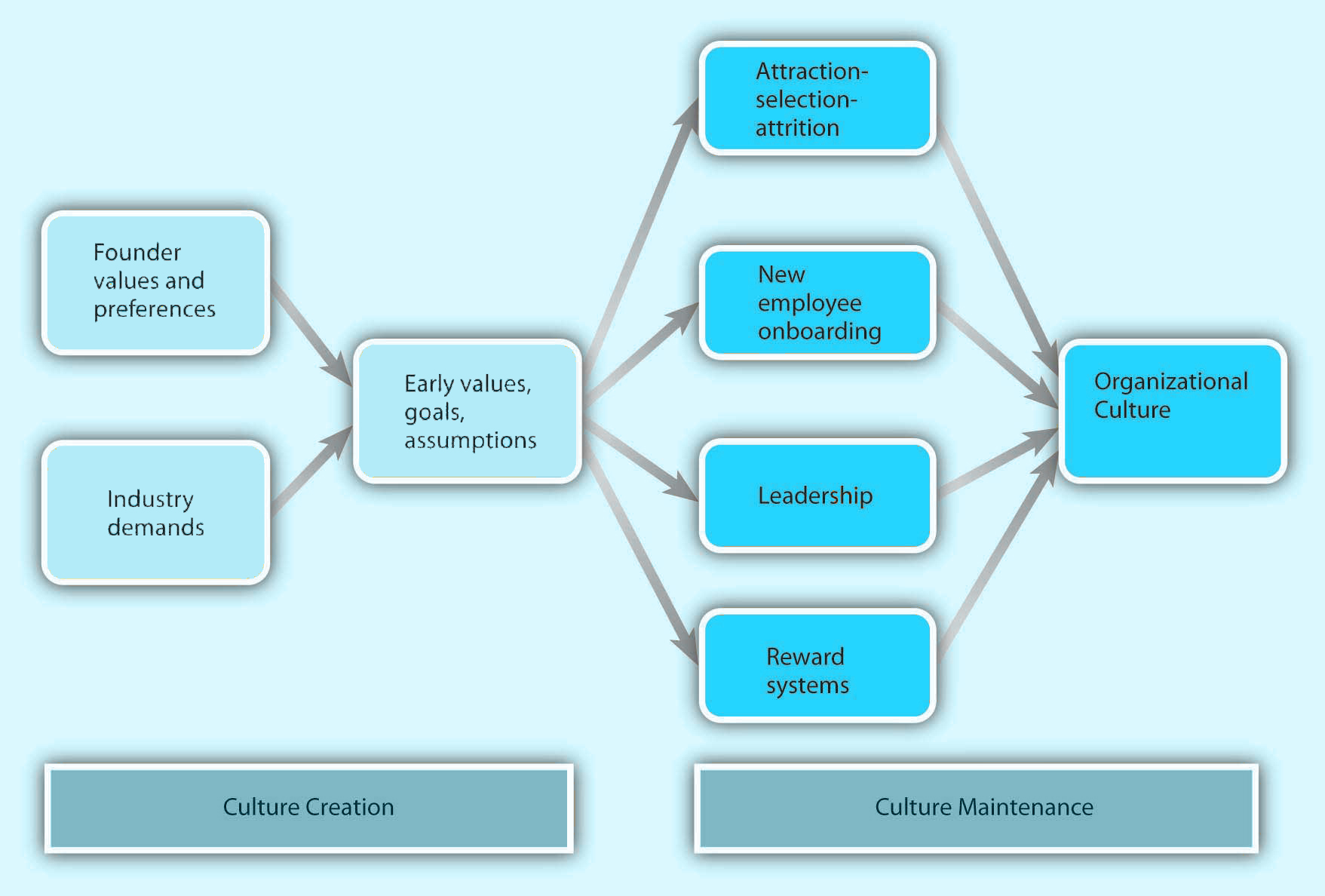

Where do cultures come from? Understanding this question is important so that you know how they can be maintained or changed. An organization’s culture is shaped as the organization faces external and internal challenges and learns how to deal with them. When the organization’s way of doing business provides a successful adaptation to environmental challenges and ensures success, those values are retained. These values and ways of doing business are taught to new members as the way to do business (Schein, 1992).

Creating Organizational Culture

The factors that are most important in the creation of an organization’s culture include founders’ values, preferences, and industry demands. Let’s talk about each of these factors in more detail.

Founder’s Values

A company’s culture, particularly during its early years, is inevitably tied to the personality, background, and values of its founder or founders, as well as their vision for the future of the organization. This explains one reason why culture is so hard to change: It is shaped in the early days of a company’s history. When entrepreneurs establish their own businesses, the way they want to do business determines the organization’s rules, the structure set-up in the company, and the people they hire to work with them.

As a case in point, some of the existing corporate values of the ice cream company Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Holdings Inc. can easily be traced to the personalities of its founders Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield. In 1978, the two ex-hippie high school friends opened up their first ice-cream shop in a renovated gas station in Burlington, Vermont. Their strong social convictions led them to buy only from the local farmers and devote a certain percentage of their profits to charities. The core values they instilled in their business can still be observed in the current company’s devotion to social activism and sustainability, its continuous contributions to charities, use of environmentally friendly materials, and dedication to creating jobs in low-income areas. Even though the company was acquired by Unilever PLC in 2000, the social activism component remains unchanged and Unilever has expressed its commitment to maintaining it (Kiger, 2005; Rubis et al., 2005; Smalley, 2007; Ben & Jerry’s, 2021).

There are many other examples of founders’ instilling their own strongly held beliefs or personalities to the businesses they found. Microsoft’s aggressive nature is often traced back to Bill Gates and his competitiveness. According to one anecdote, his competitive nature even extends to his personal life such that one of his pastimes is to compete with his wife in solving identical jigsaw puzzles to see who can finish faster (Schlender, 1998). Similarly, Joseph Pratt, a history and management professor, notes, “There definitely is an Exxon way. This is John D. Rockefeller’s company, this is Standard Oil of New Jersey, this is the one that is most closely shaped by Rockefeller’s traditions. Their values are very clear. They are deeply embedded. They have roots in 100 years of corporate history” (Mouawad, 2008).

Founder values become part of the corporate culture to the degree they help the company be successful. For example, the social activism of Ben & Jerry’s was instilled in the company because founders strongly believed in these issues. However, these values probably would not be surviving so many decades later if they had not helped the company in its initial stages. In the case of Ben & Jerry’s, these charitable values helped distinguish their brand from larger corporate brands and attracted a loyal customer base. Thus, by providing a competitive advantage, these values were retained as part of the corporate culture and were taught to new members as the right way to do business. Similarly, the early success of Microsoft may be attributed to its relatively aggressive corporate culture, which provided a source of competitive advantage.

Industry Demands

While founders undoubtedly exert a powerful influence over corporate cultures, the industry characteristics also play a role. Industry characteristics and demands act as a force to create similarities among organizational cultures. For example, despite some differences, many companies in the insurance and banking industries are stable and rule oriented, many companies in the high-tech industry have innovative cultures, and companies in the nonprofit industry tend to be people oriented. If the industry is one with a large number of regulatory requirements—for example, banking, health care, and nuclear power plant industries—then we might expect the presence of a large number of rules and regulations, a bureaucratic company structure, and a stable culture. Similarly, the high-tech industry requires agility, taking quick action, and low concern for rules and authority, which may create a relatively more innovative culture (Chatman & Jehn, 1994; Gordon, 1991). The industry influence over culture is also important to know, because this shows that it may not be possible to imitate the culture of a company in a different industry, even though it may seem admirable to outsiders.

Maintaining Organizational Culture

As a company matures, its cultural values are refined and strengthened. The early values of a company’s culture exert influence over its future values. It is possible to think of organizational culture as an organism that protects itself from external forces. Organizational culture determines who is included and excluded in the hiring process. Moreover, once new employees are hired, the company assimilates new employees and teaches them the way things are done in the organization. We call these processes attraction-selection-attrition and onboarding processes. We will also examine the role of leaders and reward systems in shaping and maintaining an organization’s culture. It is important to remember two points: The process of culture creation is in fact more complex and less clean than the name implies. Additionally, the influence of each factor on culture creation is reciprocal. For example, just as leaders may influence what type of values the company has, the culture may also determine what types of behaviors leaders demonstrate.

Attraction-Selection-Attrition (ASA)

Organizational culture is maintained through a process known as attraction-selection-attrition. First, employees are attracted to organizations where they will fit in. In other words, different job applicants will find different cultures to be attractive. Someone who has a competitive nature may feel comfortable and prefer to work in a company where interpersonal competition is the norm. Others may prefer to work in a team-oriented workplace. Research shows that employees with different personality traits find different cultures attractive. For example, out of the Big Five personality traits, employees who demonstrate neurotic personalities were less likely to be attracted to innovative cultures, whereas those who had openness to experience were more likely to be attracted to innovative cultures (Judge & Cable, 1997). As a result, individuals will self-select the companies they work for and may stay away from companies that have core values that are radically different from their own.

Of course this process is imperfect, and value similarity is only one reason a candidate might be attracted to a company. There may be other, more powerful attractions such as good benefits. For example, candidates who are potential misfits may still be attracted to Google because of the cool perks associated with being a Google employee. At this point in the process, the second component of the ASA framework prevents them from getting in: Selection. Just as candidates are looking for places where they will fit in, companies are also looking for people who will fit into their current corporate culture. Many companies are hiring people for fit with their culture, as opposed to fit with a certain job. For example, Southwest Airlines prides itself for hiring employees based on personality and attitude rather than specific job-related skills, which are learned after being hired. This is important for job applicants to know, because in addition to highlighting your job-relevant skills, you will need to discuss why your personality and values match those of the company.

Companies use different techniques to weed out candidates who do not fit with corporate values. For example, Google relies on multiple interviews with future peers. By introducing the candidate to several future coworkers and learning what these coworkers think of the candidate, it becomes easier to assess the level of fit. Companies may also use employee referrals in their recruitment process. By using their current employees as a source of future employees, companies may make sure that the newly hired employees go through a screening process to avoid potential person-culture mismatch.

Even after a company selects people for person-organization fit, there may be new employees who do not fit in. Some candidates may be skillful in impressing recruiters and signal high levels of culture fit even though they do not necessarily share the company’s values. Moreover, recruiters may suffer from perceptual biases and hire some candidates thinking that they fit with the culture even though the actual fit is low. In any event, the organization is going to eventually eliminate candidates who do not fit in through attrition. Attrition refers to the natural process in which the candidates who do not fit in will leave the company. Research indicates that person-organization misfit is one of the important reasons for employee turnover (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005; O’Reilly III et al., 1991).

As a result of the ASA process, the company attracts, selects, and retains people who share its core values. On the other hand, those people who are different in core values will be excluded from the organization either during the hiring process or later on through naturally occurring turnover. Thus, organizational culture will act as a self-defending organism where intrusive elements are kept out. Supporting the existence of such self-protective mechanisms, research shows that organizations demonstrate a certain level of homogeneity regarding personalities and values of organizational members (Giberson et al., 2005). Many organizations are currently having important conversations about diversity and inclusion and the value of attracting and retaining a more diverse workforce.

New Employee Onboarding

Another way in which an organization’s values, norms, and behavioral patterns are transmitted to employees is through onboarding (also referred to as the organizational socialization process). Onboarding refers to the process through which new employees learn the attitudes, knowledge, skills, and behaviors required to function effectively within an organization. If an organization can successfully socialize new employees into becoming organizational insiders, new employees feel confident regarding their ability to perform, sense that they will feel accepted by their peers, and understand and share the assumptions, norms, and values that are part of the organization’s culture. This understanding and confidence in turn translate into more effective new employees who perform better and have higher job satisfaction, stronger organizational commitment, and longer tenure within the company (Bauer et al., 2007).

What Can New Employees Do During Onboarding?

New employees who are proactive, seek feedback, and build strong relationships tend to be more successful than those who do not (Bauer & Green, 1998; Kammeyer-Mueller & Wanberg, 2003; Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). For example, feedback seeking helps new employees. Especially on a first job, a new employee can make mistakes or gaffes and may find it hard to understand and interpret the ambiguous reactions of coworkers. New hires may not know whether they are performing up to standards, whether it was a good idea to mention a company mistake in front of a client, or why other employees are asking if they were sick over the weekend because of not responding to work-related emails. By actively seeking feedback, new employees may find out sooner rather than later any behaviors that need to be changed and gain a better understanding of whether their behavior fits with the company culture and expectations. Several studies show the benefits of feedback seeking for new employee adjustment. We will talk more about strategies for giving and receiving feedback in future chapters of this book.

Relationship building, or networking, is another important behavior new employees may demonstrate. Particularly when a company does not have a systematic approach to onboarding, it becomes more important for new employees to facilitate their own onboarding by actively building relationships. According to one estimate, 35% of managers who start a new job fail in the new job and either voluntarily leave or are fired within 1.5 years. Of these, over 60% report not being able to form effective relationships with colleagues as the primary reason for their failure (Fisher, 2005). New employees may take an active role in building relations by seeking opportunities to have a conversation with their new colleagues, arranging lunches or coffee with them, participating in company functions, and making the effort to build a relationship with their new supervisor (Kim et al., 2005).

Consider This: Tips for the Onboarding Process

You’ve Got a New Job! Now How Do You Get on Board?

Here are some suggestions about how to engage in the onboarding process at a new job:

- Gather information. Try to find as much about the company and the job as you can before your first day. After you start working, be a good observer, gather information, and read as much as you can to understand your job and the company. Examine how people are interacting, how they dress, and how they act to avoid behaviors that might indicate to others that you are a misfit.

- Manage your first impression. First impressions may endure, so make sure that you dress appropriately, are friendly, and communicate your excitement to be a part of the team. Be on your best behavior!

- Invest in relationship development. The relationships you develop with your manager and with coworkers will be essential for you to adjust to your new job. Take the time to strike up conversations with them. If there are work functions during your early days, make sure not to miss them!

- Seek feedback. Ask your manager or coworkers how well you are doing and whether you are meeting expectations. Listen to what they are telling you and also listen to what they are not saying. Then, make sure to act upon any suggestions for improvement. Be aware that after seeking feedback, you may create a negative impression if you consistently ignore the feedback you receive.

- Show success early on. In order to gain the trust of your new manager and colleagues, you may want to establish a history of success early. Volunteer for high-profile projects where you will be able to demonstrate your skills. Alternatively, volunteer for projects that may serve as learning opportunities or that may put you in touch with the key people in the company.

Source: Adapted from ideas in Beagrie, (2005).

What Can Organizations Do During Onboarding?

Many organizations, including Microsoft, Kellogg Company, and Bank of America, take a more structured and systematic approach to new employee onboarding, while others follow a “sink or swim” approach in which new employees struggle to figure out what is expected of them and what the norms are.

A formal orientation program indoctrinates new employees to the company culture, as well as introduces them to their new jobs and colleagues. An orientation program is important, because it has a role in making new employees feel welcome in addition to imparting information that may help new employees be successful on their new jobs. Many large organizations have formal orientation programs consisting of lectures, video lectures and written material, while some may follow more unusual approaches. According to one estimate, most orientations last anywhere from one to five days, and many companies are currently switching to a computer-based orientation. Research shows that formal orientation programs are helpful in teaching employees about the goals and history of the company, as well as communicating the power structure. Moreover, these programs may also help with a new employee’s integration into the team.

One of the most important ways in which organizations can help new employees adjust to a company and a new job is through organizational insiders—namely supervisors, coworkers, and mentors. Research shows that leaders have a key influence over onboarding, and the information and support leaders provide determine how quickly employees learn about the company politics and culture. Coworker influence determines the degree to which employees adjust to their teams.

Mentors can be crucial to helping new employees adjust by teaching them the ins and outs of their jobs and how the company really operates. A mentor is a trusted person who provides an employee with advice and support regarding career-related matters. Although a mentor can be any employee or manager who has insights that are valuable to the new employee, mentors tend to be relatively more experienced than their protégés. Mentoring can occur naturally between two interested individuals, or organizations can facilitate this process by having formal mentoring programs. These programs may successfully bring together mentors and protégés who would not come together otherwise.

Research indicates that the existence of these programs does not guarantee their success, and there are certain program characteristics that may make these programs more effective. For example, when mentors and protégés feel that they had input in the mentor-protégé matching process, they tend to be more satisfied with the arrangement. Moreover, when mentors receive training beforehand, the outcomes of the program tend to be more positive (Allen et al., 2006). Because mentors may help new employees interpret and understand the company’s culture, organizations may benefit from selecting mentors who personify the company’s values. Thus, organizations may need to design these programs carefully to increase their chance of success.

Leadership

While subcultures develop in organizations, the larger organization’s culture influences these, especially with strong leaders and leadership teams who set the tone at the top and communicate expectations and performance standards throughout.

Leaders are instrumental in creating and changing an organization’s culture. There is a direct correspondence between a leader’s style and an organization’s culture. For example, when leaders motivate employees through inspiration, corporate culture tends to be more supportive and people oriented. When leaders motivate by making rewards contingent on performance, the corporate culture tends to be more performance oriented and competitive (Sarros et al., 2002). In these and many other ways, what leaders do directly influences the cultures their organizations have.

Part of the leader’s influence over culture is through role modeling. Many studies have suggested that leader behavior, the consistency between organizational policy and leader actions, and leader role modeling determine the degree to which the organization’s culture emphasizes ethics (Driscoll & McKee, 2007). The leader’s own behaviors will signal to employees what is acceptable behavior and what is unacceptable. In an organization in which high-level managers make the effort to involve others in decision making and seek opinions of others, a team-oriented culture is more likely to evolve. By acting as role models, leaders send signals to the organization about the norms and values that are expected to guide the actions of organizational members.

Leaders also shape culture by their reactions to the actions of others around them. For example, do they praise a job well done, or do they praise a favored employee regardless of what was accomplished? How do they react when someone admits to making an honest mistake? What are their priorities? In meetings, what types of questions do they ask? Do they want to know what caused accidents so that they can be prevented, or do they seem more concerned about how much money was lost as a result of an accident? Do they seem outraged when an employee is disrespectful to a coworker, or does their reaction depend on whether they like the harasser? Through their day-to-day actions, leaders shape and maintain an organization’s culture.

Reward Systems

Finally, the company culture is shaped by the type of reward systems used in the organization, and the kinds of behaviors and outcomes it chooses to reward and punish. One relevant element of the reward system is whether the organization rewards behaviors or results. Some companies have reward systems that emphasize intangible elements of performance as well as more easily observable metrics. In these companies, supervisors and peers may evaluate an employee’s performance by assessing the person’s behaviors as well as the results. In such companies, we may expect a culture that is relatively people or team oriented, and employees act as part of a family (Kerr & Slocum Jr., 2005).

On the other hand, in companies that purely reward goal achievement, there is a focus on measuring only the results without much regard to the process. In these companies, we might observe outcome-oriented and competitive cultures. Another categorization of reward systems might be whether the organization uses rankings or ratings. In a company where the reward system pits members against one another, where employees are ranked against each other and the lower performers receive long-term or short-term punishments, it would be hard to develop a culture of people orientation and may lead to a competitive culture. Evaluation systems that reward employee behavior by comparing them to absolute standards as opposed to comparing employees to each other may pave the way to a team-oriented culture. Whether the organization rewards performance or seniority would also make a difference in culture. When promotions are based on seniority, it would be difficult to establish a culture of outcome orientation.

Finally, the types of behaviors that are rewarded or ignored set the tone for the culture. Service-oriented cultures reward, recognize, and publicize exceptional service on the part of their employees. In safety cultures, safety metrics are emphasized and the organization is proud of its low accident ratings. What behaviors are rewarded, which ones are punished, and which are ignored will determine how a company’s culture evolves.

External Influences on Organizational Culture

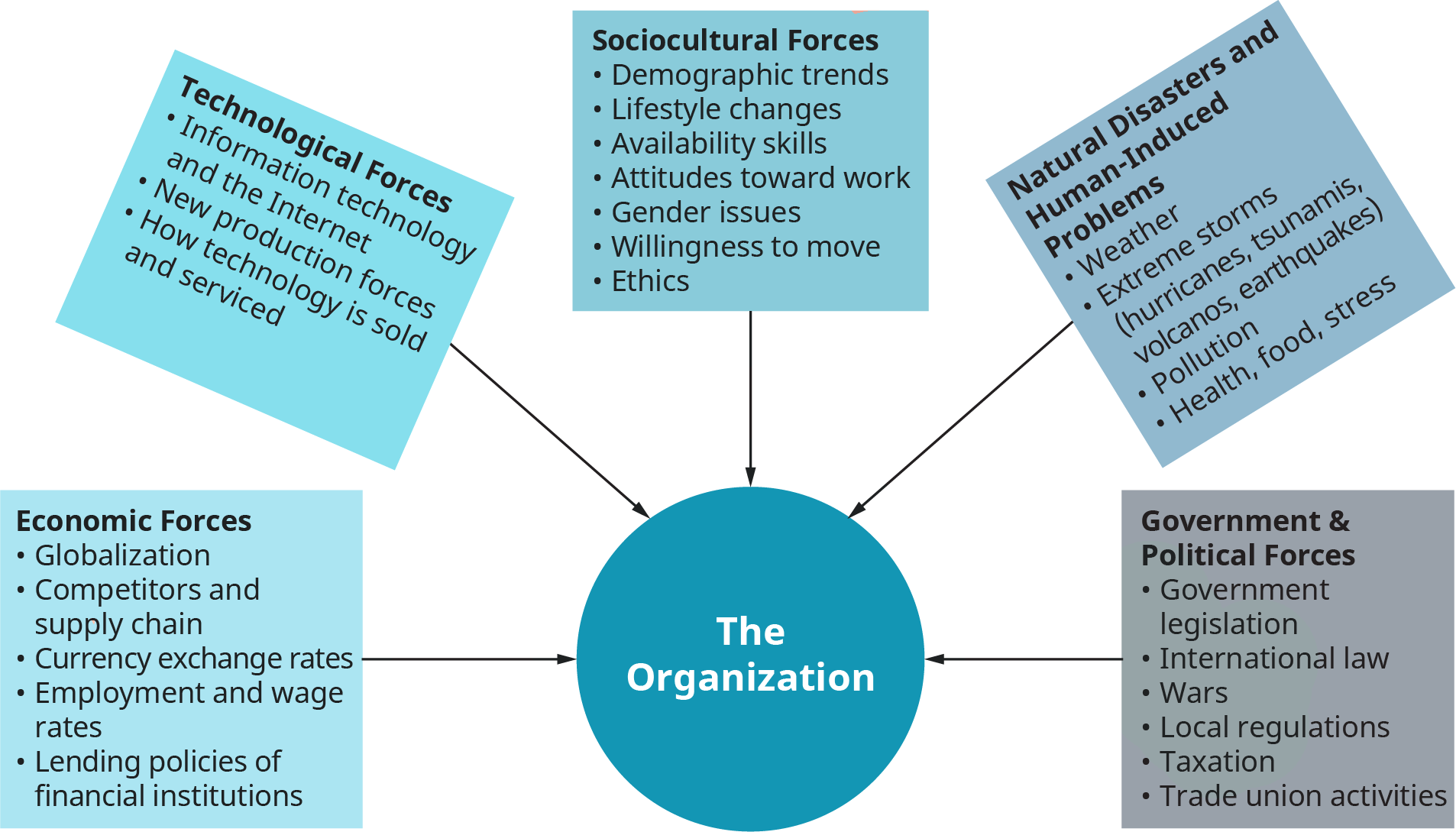

To succeed and thrive, organizations must adapt, exploit, and fit with the forces in their external environments. Organizations are groups of people deliberately formed together to serve a purpose through structured and coordinated goals and plans. As such, organizations operate in different external environments and are organized and structured internally to meet both external and internal demands and opportunities. Different types of organizations include not-for-profit, for-profit, public, private, government, voluntary, family owned and operated, and publicly traded on stock exchanges. Organizations are commonly referred to as companies, firms, corporations, institutions, agencies, associations, groups, consortiums, and conglomerates. While the type, size, scope, location, purpose, and mission of an organization all help determine the external environment in which it operates, it still must meet the requirements and contingencies of that environment to survive and prosper. In this section, we consider how organizations are structured to meet challenges and opportunities of these environments.

Figure 3.3 illustrates types of general macro environments and forces that are interrelated and affect organizations: sociocultural, technological, economic, government and political, natural disasters, and human-induced problems that affect industries and organizations. For example, economic environmental forces generally include such elements in the economy as exchange rates and wages, employment statistics, and related factors such as inflation, recessions, and other shocks—negative and positive. Hiring and unemployment, employee benefits, factors affecting organizational operating costs, revenues, and profits are affected by global, national, regional, and local economies. Other factors discussed here that interact with economic forces include politics and governmental policies, international wars, natural disasters, technological inventions, and sociocultural forces. It is important to keep these dimensions in mind when studying organizations since many if not most or all changes that affect organizations originate from one or more of these sources—many of which are interrelated.

Changing Organizational Culture

Culture is often deeply ingrained and resistant to change efforts. Unfortunately, many organizations may not even realize that their current culture constitutes a barrier against organizational productivity and performance. Changing company culture may be the key to the company turnaround when there is a mismatch between an organization’s values and the demands of its environment.

Sometimes the external environment may force an organization to undergo culture change. For example, if an organization is experiencing failure in the short run or is under threat of bankruptcy or an imminent loss of market share, it would be easier to convince managers and employees that culture change is necessary. A company can use such downturns to generate employee commitment to the change effort. However, if the organization has been successful in the past, and if employees do not perceive an urgency necessitating culture change, the change effort will be more challenging.

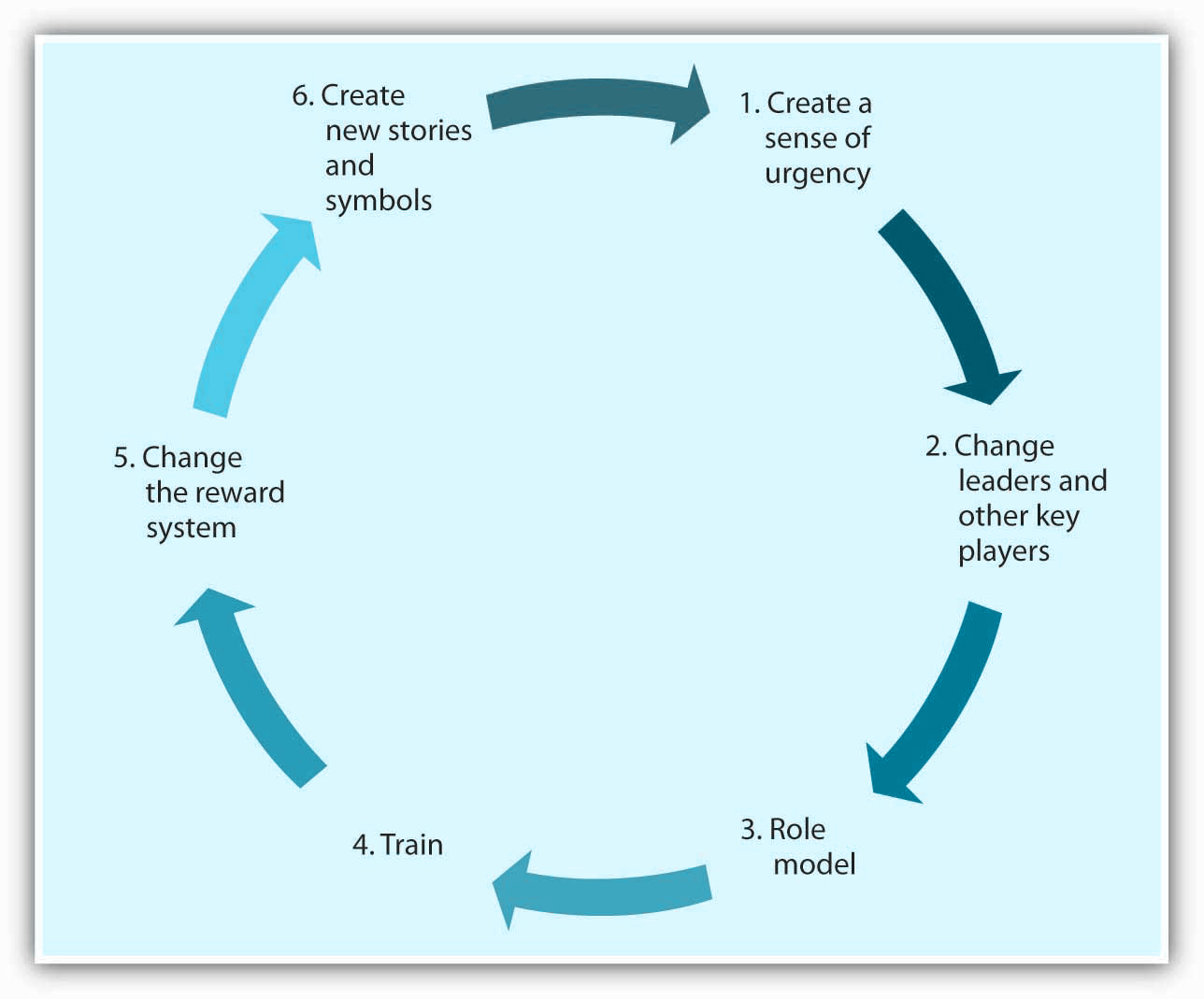

Mergers and acquisitions are another example of an event that changes a company’s culture. In fact, the ability of the two merging companies to harmonize their corporate cultures is often what makes or breaks a merger effort. Achieving culture change is challenging, and many companies ultimately fail in this mission. Research and case studies of companies that successfully changed their culture indicate that the following six steps increase the chances of success (Schein, 1990). Alternate models of change include Lewin’s 3-stage model, Kotter’s 8-stage model, and appreciative inquiry. For brevity, we will only discuss Schein’s 6 steps.

Six Steps to Culture Change: 1) Create a sense of urgency, 2) Change leaders and other key players, 3) Role model, 4) Train, 5) Change the reward system, 6) Create new stories and symbols

Step 1: Creating a Sense of Urgency

In order for the change effort to be successful, it is important to communicate the need for change to employees. One way of doing this is to create a sense of urgency on the part of employees and explain to them why changing the fundamental way in which business is done is so important. In successful culture change efforts, leaders communicate with employees and present a case for culture change as the essential element that will lead the company to eventual success.

Step 2: Changing Leaders and Other Key Players

A leader’s vision is an important factor that influences how things are done in an organization. Thus, culture change often follows changes at the highest levels of the organization. Moreover, in order to implement the change effort quickly and efficiently, a company may find it helpful to remove managers and other powerful employees who are acting as a barrier to change. Because of political reasons, self interest, or habits, managers may create powerful resistance to change efforts. In such cases, replacing these positions with employees and managers giving visible support to the change effort may increase the likelihood that the change effort succeeds.

Step 3: Role Modeling

Role modeling is the process by which employees modify their own beliefs and behaviors to reflect those of the leader (Kark & Van Dijk, 2007). CEOs can model the behaviors that are expected of employees to change the culture. The ultimate goal is that these behaviors will trickle down to lower level employees.

Step 4: Training

Well-crafted training programs may be instrumental in bringing about culture change by teaching employees the new norms and behavioral styles. For example, after the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon reentry from a February 2003 mission, NASA decided to change its culture to become more safety sensitive and minimize decision-making errors leading to unsafe behaviors. The change effort included training programs in team processes and cognitive bias awareness (NASA, 2004).

Step 5: Changing the Reward System

The criteria with which employees are rewarded and punished have a powerful role in determining the cultural values in existence. Switching from a commission-based incentive structure to a straight salary system may be instrumental in bringing about customer focus among sales employees. Moreover, by rewarding employees who embrace the company’s new values and even promoting these employees, organizations can make sure that changes in culture have a lasting impact. If a company wants to develop a team-oriented culture where employees collaborate with each other, methods such as using individual-based incentives may backfire. Instead, distributing bonuses to intact teams might be more successful in bringing about culture change.

Step 6: Creating New Symbols and Stories

Finally, the success of the culture change effort may be increased by developing new rituals, symbols, and stories. By replacing the old symbols and stories, the new symbols and stories will help enable the culture change and ensure that the new values are communicated.

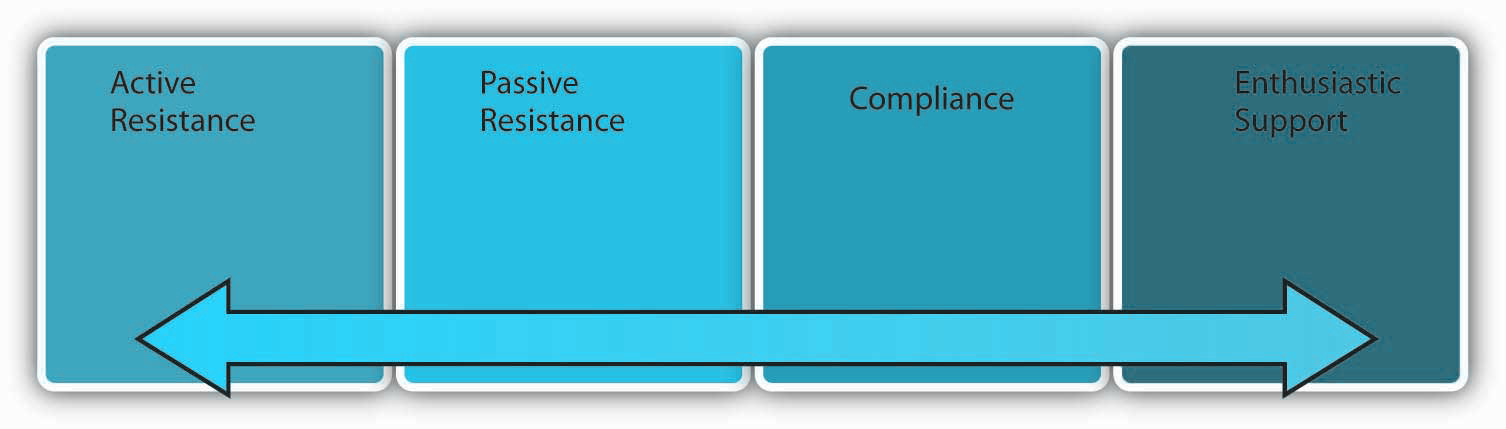

Reactions to Change

Active resistance is the most negative reaction to a proposed change attempt. Those who engage in active resistance may sabotage the change effort and be outspoken objectors to the new procedures. In contrast, passive resistance involves being disturbed by changes without necessarily voicing these opinions. Instead, passive resisters may quietly dislike the change, feel stressed and unhappy, and even look for an alternative job without necessarily bringing their point to the attention of decision makers. Compliance, on the other hand, involves going along with proposed changes with little enthusiasm. Finally, those who show enthusiastic support are defenders of the new way and actually encourage others around them to give support to the change effort as well.

Any change attempt will have to overcome the resistance on the part of people to be successful. Otherwise, the result will be loss of time and energy as well as an inability on the part of the organization to adapt to the changes in the environment and make its operations more efficient. Resistance to change also has negative consequences for the people in question. Research shows that when people negatively react to organizational change, they experience negative emotions, use sick time more often, and are more likely to voluntarily leave the company (Fugate et al., 2008).

Resistance to change may be a positive force in some instances. In fact, resistance to change is a valuable feedback tool that should not be ignored. Why are people resisting the proposed changes? Do they feel that the new system will not work? If so, why not? By listening to people and incorporating their suggestions into the change effort, it is possible to make a more effective change. Some of a company’s most committed employees may be the most vocal opponents of a change effort. They may fear that the organization they feel such a strong attachment to is being threatened by the planned change effort and the change will ultimately hurt the company. In contrast, people who have less loyalty to the organization may comply with the proposed changes simply because they do not care enough about the fate of the company to oppose the changes. As a result, when dealing with those who resist change, it is important to avoid blaming them for a lack of loyalty (Ford et al., 2008).

Let’s Focus: Overcome Resistance to Your Proposals

You feel that change is needed. You have a great idea. But people around you do not seem convinced. They are resisting your great idea. How do you make change happen?

You feel that change is needed. You have a great idea. But people around you do not seem convinced. They are resisting your great idea. How do you make change happen?

- Listen to naysayers. You may think that your idea is great, but listening to those who resist may give you valuable ideas about why it may not work and how to design it more effectively.

- Is your change revolutionary? If you are trying to dramatically change the way things are done, you will find that resistance is greater. If your proposal involves incrementally making things better, you may have better luck.

- Involve those around you in planning the change. Instead of providing the solutions, make them part of the solution. If they admit that there is a problem and participate in planning a way out, you would have to do less convincing when it is time to implement the change.

- Do you have credibility? When trying to persuade people to change their ways, it helps if you have a history of suggesting implementable changes. Otherwise, you may be ignored or met with suspicion. This means you need to establish trust and a history of keeping promises over time before you propose a major change.

- Present data to your audience.Be prepared to defend the technical aspects of your ideas and provide evidence that your proposal is likely to work.

- Appeal to your audience’s ideals. Frame your proposal around the big picture. Are you going to create happier clients? Is this going to lead to a better reputation for the company? Identify the long-term goals you are hoping to accomplish that people would be proud to be a part of.

- Understand the reasons for resistance. Is your audience resisting because they fear change? Does the change you propose mean more work for them? Does it impact them in a negative way? Understanding the consequences of your proposal for the parties involved may help you tailor your pitch to your audience.

Sources: McGoon, (1995) and Stanley, (2002).

Common Reasons for Resisting Change

Resisting change can be a source of conflict in the workplace. Let’s discuss some of the common reasons that people are resistant to change.

Disrupted Habits

People often resist change for the simple reason that change disrupts our habits. You may find that for this simple reason, people sometimes are surprisingly outspoken when confronted with simple changes such as updating to a newer version of a particular software or a change in their voice mail system.

Personality

Some people are more resistant to change than others. Research shows that people who have a positive self-concept are better at coping with change, probably because those who have high self-esteem may feel that whatever the changes are, they are likely to adjust to it well and be successful in the new system. People with a more positive self-concept and those who are more optimistic may also view change as an opportunity to shine as opposed to a threat that is overwhelming. Finally, risk tolerance is another predictor of how resistant someone will be to stress. For people who are risk avoidant, the possibility of a change in technology or structure may be more threatening (Judge et al., 1999; Wanber & Banas, 2000).

Feelings of Uncertainty

Change inevitably brings feelings of uncertainty. You have just heard that your company is merging with another. What would be your reaction? Such change is often turbulent, and it is often unclear what is going to happen to each individual. Some positions may be eliminated. Some people may see a change in their job duties. Things can get better—or they may get worse. The feeling that the future is unclear is enough to create stress for people, because it leads to a sense of lost control (Ashford et al., 1989; Fugate et al., 2008)

Fear of Failure

People also resist change when they feel that their performance may be affected under the new system. People who are experts in their jobs may be less than welcoming of the changes, because they may be unsure whether their success would last under the new system. Studies show that people who feel that they can perform well under the new system are more likely to be committed to the proposed change, while those who have lower confidence in their ability to perform after changes are less committed (Herold et al., 2007).

Personal Impact of Change

It would be too simplistic to argue that people resist all change, regardless of its form. In fact, people tend to be more welcoming of change that is favorable to them on a personal level (such as giving them more power over others, or change that improves quality of life such as bigger and nicer offices). Research also shows that commitment to change is highest when proposed changes affect the work unit with a low impact on how individual jobs are performed (Fedor et al., 2006).

Prevalence of Change

Any change effort should be considered within the context of all the other changes that are introduced in a company. Does the company have a history of making short-lived changes? If the company structure went from functional to product-based to geographic to matrix within the past 5 years, and the top management is in the process of going back to a functional structure again, a certain level of resistance is to be expected because people are likely to be fatigued as a result of the constant changes. Moreover, the lack of a history of successful changes may cause people to feel skeptical toward the newly planned changes. Therefore, considering the history of changes in the company is important to understanding why people resist. Also, how big is the planned change? If the company is considering a simple switch to a new computer program, such as introducing Microsoft Access for database management, the change may not be as extensive or stressful compared to a switch to an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system such as SAP or PeopleSoft, which require a significant time commitment and can fundamentally affect how business is conducted (Labianca et al., 2000; Rafferty & Griffin, 2006).

Perceived Loss of Power

One other reason why people may resist change is that change may affect their power and influence in the organization. Imagine that your company moved to a more team-based structure, turning supervisors into team leaders. In the old structure, supervisors were in charge of hiring and firing all those reporting to them. Under the new system, this power is given to the team itself. Instead of monitoring the progress the team is making toward goals, the job of a team leader is to provide support and mentoring to the team in general and ensure that the team has access to all resources to be effective. Given the loss in prestige and status in the new structure, some supervisors may resist the proposed changes even if it is better for the organization to operate around teams.

Case Study

Adapted Works

“Creating and Maintaining Organizational Culture” in Organizational Behavior by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Managing Change” in Principles of Management by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Organizational Change” in Organizational Behaviour by Saylor Academy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

“Conflict and Negotiations” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax and is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Employee Orientation and Training” in Principles of Management by Lisa Jo Rudy & Lumen Learning and is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

Allen, T. D., Eby, L. T., & Lentz, E. (2006). Mentorship behaviors and mentorship quality associated with formal mentoring programs: Closing the gap between research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 567–578.

Ashford, S. J., Lee, C. L., & Bobko, P. (1989). Content, causes, and consequences of job insecurity: A theory-based measure and substantive test. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 803–829.

Bauer, T. N., Bodner, T., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Tucker, J. S. (2007). Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 707–721.

Bauer, T. N., & Green, S. G. (1998). Testing the combined effects of newcomer information seeking and manager behavior on socialization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 72–83.

Beagrie, S. (2005, March 1). How to…survive the first six months of a new job. Personnel Today, 27.

Ben & Jerry’s. (2021). Issues we care about. https://www.benjerry.com/values/issues-we-care-about

Chatman, J. A., & Jehn, K. A. (1994). Assessing the relationship between industry characteristics and organizational culture: How different can you be? Academy of Management Journal, 37, 522–553.

Driscoll, K., & McKee, M. (2007). Restorying a culture of ethical and spiritual values: A role for leader storytelling. Journal of Business Ethics, 73, 205–217.

Fedor, D. M., Caldwell, S., & Herold, D. M. (2006). The effects of organizational changes on employee commitment: A multilevel investigation. Personnel Psychology, 59, 1–29.

Fisher, A. (2005, March 7). Starting a new job? Don’t blow it. Fortune, 151, 48.

Ford, J. D., Ford, L. W., & D’Amelio, A. (2008). Resistance to change: The rest of the story. Academy of Management Review, 33, 362–377.

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Prussia, G. E. (2008). Employee coping with organizational change: An examination of alternative theoretical perspectives and models. Personnel Psychology, 61, 1–36.

Giberson, T. R., Resick, C. J., & Dickson, M. W. (2005). Embedding leader characteristics: An examination of homogeneity of personality and values in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1002–1010.

Gordon, G. G. (1991). Industry determinants of organizational culture. Academy of Management Review, 16, 396–415.

Herold, D. M., Fedor D. B., & Caldwell, S. (2007). Beyond change management: A multilevel investigation of contextual and personal influences on employees’ commitment to change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 942–951.

Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (1997). Applicant personality, organizational culture, and organization attraction. Personnel Psychology, 50, 359–394.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Pucik, V., & Welbourne, T. M. (1999). Managerial coping with organizational change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 107–122.

Labianca, G., Gray, B., & Brass D. J. (2000). A grounded model of organizational schema change during empowerment. Organization Science, 11, 235–257.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. Harper & Row.

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Wanberg, C. R. (2003). Unwrapping the organizational entry process: Disentangling multiple antecedents and their pathways to adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 779–794.

Kark, R., & Van Dijk, D. (2007). Motivation to lead, motivation to follow: The role of the self-regulatory focus in leadership processes. Academy of Management Review, 32, 500–528.

Kerr, J., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (2005). Managing corporate culture through reward systems. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 130–138.

Kiger, P. J. (April, 2005). Corporate crunch. Workforce Management, 84, 32–38.

Kim, T., Cable, D. M., & Kim, S. (2005). Socialization tactics, employee proactivity, and person-organization fit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 232–241.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342.

McGoon, C. (1995, March). Secrets of building influence. Communication World, 12(3), 16.

Mouawad, J. (2008, November 16). Exxon doesn’t plan on ditching oil. International Herald Tribune. http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/11/16/business/16exxon.php

NASA. (2004). BST to guide culture change effort at NASA. Professional Safety, 49, 16.

O’Reilly III, C. A., Chatman, J. A., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

Rafferty, A. E., & Griffin. M. A. (2006). Perceptions of organizational change: A stress and coping perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1154–1162.

Rubis, L., Fox, A., Pomeroy, A., Leonard, B., Shea, T. F., Moss, D., Kraft, G., & Overman, S. (2005). 50 for history. HR Magazine, 50(13), 10–24.

Sarros, J. C., Gray, J., & Densten, I. L. (2002). Leadership and its impact on organizational culture. International Journal of Business Studies, 10, 1–26.

Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture. American Psychologist, 45, 109–119.

Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass.

Schein, E. (2017). Organizational culture and leadership (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Schlender, B. (1998, June 22). Gates’ crusade. Fortune, 137, 30–32.

Smalley, S. (2007, December 3). Ben & Jerry’s bitter crunch. Newsweek, 150, 50.

Stanley, T. L. (2002, January). Change: A common-sense approach. Supervision, 63(1), 7–10.

Wanberg, C. R., & Banas, J. T. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of openness to changes in a reorganizing workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 132–142.

Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 373–385.