8.1 Theories of Motivation

Motivation

Motivation refers to an internally generated drive to achieve a goal or follow a particular course of action. Highly motivated employees focus their efforts on achieving specific goals. Motivated employees call in sick less frequently, are more productive, and are less likely to convey bad attitudes to customers and coworkers. They also tend to stay in their jobs longer, reducing turnover and the cost of hiring and training employees.

You might be wondering: what is the connection is between motivation and conflict? In Chapter 7 we learned that both affect and emotion drive our behaviours. If we perceive that someone is the source of our inability to meet our needs or goals, a conflict may arise. In this section we will discuss two theories of motivation and how they might help us to understand conflict at work.

In this section:

Hierarchy of Needs Theory

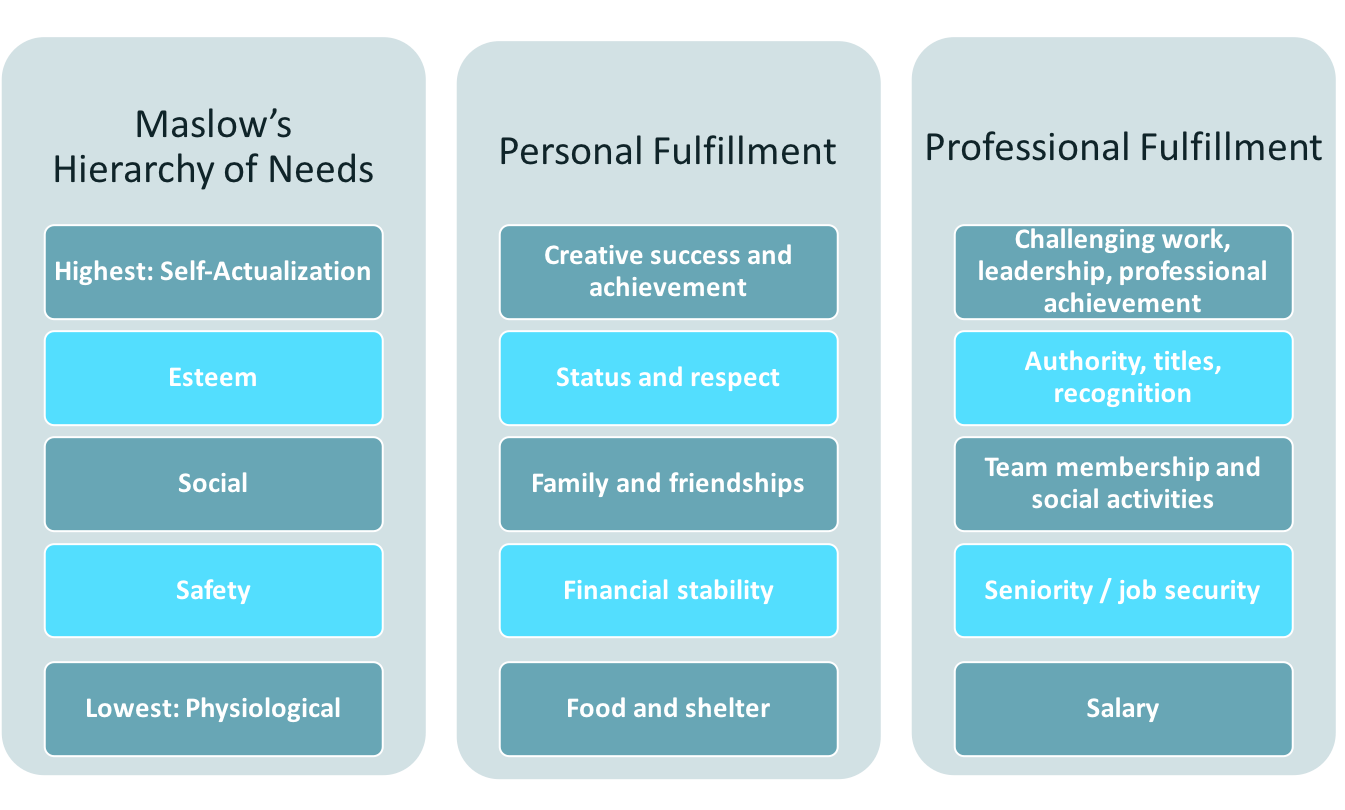

Psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory (1943, 1954), proposed that we are motivated by the five initially unmet needs, arranged in the hierarchical order shown below, which also lists specific examples of each type of need in both the personal and work spheres of life. Look, for instance, at the list of personal needs in the middle column. At the bottom are physiological needs (such life-sustaining needs as food and shelter). Working up the hierarchy we experience safety needs (financial stability, freedom from physical harm), social needs (the need to belong and have friends), esteem needs (the need for self-respect and status), and self-actualization needs (the need to reach one’s full potential or achieve some creative success).

Let’s say, for example, that for a variety of reasons that aren’t your fault, you’re broke, hungry, and homeless. Because you’ll probably take almost any job that will pay for food and housing (physiological needs), you go to work at a local recycling plant. Fortunately, your student loan finally comes through, and with enough money to feed yourself, you can go back to school and look for a job that’s not so risky (a safety need). You find a job as a night janitor in the library, and though you feel secure, you start to feel cut off from your friends, who are active during daylight hours. You want to work among people, not books (a social need). So now you join several of your friends selling pizza in the student centre. This job improves your social life, but even though you’re very good at making pizzas, it’s not terribly satisfying. You’d like something that your friends will respect enough to stop teasing you about the pizza job (an esteem need). So you study hard and land a job as an intern in a PR firm. On graduation, you move up through a series of department. When you get promoted to the head of your department, you realize that you’ve reached your full potential (a self-actualization need) and you comment to yourself, “It doesn’t get any better than this.”

What implications does Maslow’s theory have for the workplace? There are two key points: (1) Not all employees are driven by the same needs, and (2) the needs that motivate individuals can change over time. Managers should consider which needs different employees are trying to satisfy and should structure rewards and other forms of recognition accordingly. For example, when you got your first job, you were motivated by the need for money to buy food. If you’d been given a choice between a raise or a plaque recognizing your accomplishments, you’d undoubtedly have opted for the money. As department head with a good paying salary, you may prefer public recognition of work well done to a pay raise.

Needs Theory and Conflict

The idea of meeting these needs at work ties into many of the ideas discussed in previous chapters of this book. For example, I think that it’s fair to say that most of us are not functioning at our best when our most basic human physiological needs are unmet. If you find yourself irritable and having difficulty controlling your emotions, it can be helpful to reflect on whether you are hungry, sick, or tired. If this is the case, taking a break and ensuring your basic bodily needs are met can be important to address before trying to work out a conflict. At work, we can recognize the importance of safety needs in the form of job security. As we have discussed in previous chapters, lack of emotional safety (e.g., bullying and harassment) can also have a negative impact on an individual’s health and ability to deal with stressors at work. Social needs at work can be understood in terms of the quality of our interpersonal relationships at work, team dynamics, and even organizational culture. In this way, we can look at meeting basic needs as a way to prevent and manage conflict.’

Meeting Esteem Needs through Job Design, Job Enlargement, and Empowerment

As we have discussed previously, one of the reasons for job dissatisfaction and conflict is the job itself. Ensuring our skills set and what we enjoy doing matches with the job is important. Some companies will use a change in job design, enlarge the job or empower employees to motivate them and help people to meet their esteem needs.

Job enrichment means to enhance a job by adding more meaningful tasks to make our work more rewarding. For example, if we as retail salespersons are good at creating eye-catching displays, allowing us to practice these skills and assignment of tasks around this could be considered job enrichment.

Job enrichment can fulfill our higher level of human needs while creating job satisfaction at the same time. In fact, research in this area by Richard Hackman and Greg Oldham (Ford, 1969; Paul et al., 1969) found that we, as employees, need the following to achieve job satisfaction:

- Skill variety, or many different activities as part of the job

- Task identity, or being able to complete one task from beginning to end

- Task significance, or the degree to which the job has an impact on others, internally or externally

- Autonomy, or freedom to make decisions within the job

- Feedback, or clear information about performance

In addition, job enlargement, defined as the adding of new challenges or responsibilities to a current job, can create job satisfaction. Assigning us to a special project or task is an example of job enlargement.

Employee empowerment involves management allowing us to make decisions and act upon those decisions, with the support of the organization. When we are not micromanaged and have the power to determine the sequence of our own workday, we tend to be more satisfied than those employees who are not empowered. Empowerment can include the following:

- Encourage innovation or new ways of doing things.

- Make sure we, as employees, have the information we need to do our jobs; for example, we are not dependent on managers for information in decision making.

- Management styles that allow for participation, feedback, and ideas from employees.

Equity Theory

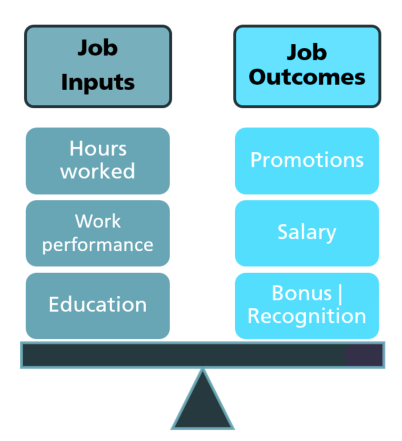

A second theory of motivation that we will discuss in relationship to conflict at work is equity theory, which focuses on our perceptions of how fairly we’re treated relative to others. Applied to the work environment, this theory proposes that employees analyze their contributions or job inputs (hours worked, education, experience, work performance) and their rewards or job outcomes (salary, bonus, promotion, recognition). Then they create a contributions/rewards ratio and compare it to those of other people. The basis of comparison can be any one of the following:

- Someone in a similar position

- Someone holding a different position in the same organization

- Someone with a similar occupation

- Someone who shares certain characteristics (such as age, education, or level of experience)

- Oneself at another point in time

When individuals perceive that the ratio of their contributions to rewards is comparable to that of others, they perceive that they’re being treated fairly or equitably; when they perceive that the ratio is out of balance, they perceive inequity. Occasionally, people will perceive that they’re being treated better than others. More often, however, they conclude that others are being treated better (and that they themselves are being treated worse).

What will an employee do if they perceives an inequity? The individual might try to bring the ratio into balance, either by decreasing inputs (working fewer hours, not taking on additional tasks) or by increasing outputs (asking for a raise). If this strategy fails, an employee might complain to a supervisor, transfer to another job, leave the organization, or rationalize the situation (e.g., deciding that the situation isn’t so bad after all). Equity theory advises managers to focus on treating workers fairly, especially in determining compensation, which is, naturally, a common basis of comparison.

Let’s Focus: Conflict Management and Fairness

Perceptions on fairness and how organizations handle conflict can be a contributing factor to our motivation at work. Outcome fairness refers to the judgment that we make with respect to the outcomes we receive versus the outcomes received by others with whom we associate with. When we are deciding if something is fair, we will likely look at procedural justice, or the process used to determine the outcomes received. There are six main areas we use to determine the outcome fairness of a conflict:

Perceptions on fairness and how organizations handle conflict can be a contributing factor to our motivation at work. Outcome fairness refers to the judgment that we make with respect to the outcomes we receive versus the outcomes received by others with whom we associate with. When we are deciding if something is fair, we will likely look at procedural justice, or the process used to determine the outcomes received. There are six main areas we use to determine the outcome fairness of a conflict:

- Consistency. We will determine if the procedures are applied consistently to other persons and throughout periods of time.

- Bias suppression. We perceive the person making the decision does not have a bias or vested interest in the outcome.

- Information accuracy. The decision made is based on correct information.

- Correctability. The decision is able to be appealed and mistakes in the decision process can be corrected.

- Representativeness. We feel the concerns of all stakeholders involved have been taken into account.

- Ethicality. The decision is in line with moral societal standards.

For example, let’s suppose Shyla just received a bonus and recognition at the company party for her contributions to an important company project. However, you might compare your inputs and outputs and determine it was unfair that Shyla was recognized because you had worked on bigger projects and not received the same recognition or bonus. As you know, this type of unfairness can result in being unmotivated at work and also the root of conflict.

Adapted Works

“Motivating Employees” in Fundamentals of Business: Canadian Edition by Pamplin College of Business and Virginia Tech Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Strategies Used to Increase Motivation” in Human Relations by Saylor Academy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

References

Ford, R. N. (1969). Motivation through the work itself. American Management Association.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper.

Paul, W. J., Robertson, K. B., & Herzberg, F. (1969). Job enrichment pays off. Harvard Business Review, 61–78.