10.3 Listening

In this section:

Listening

When it comes to daily communication, we spend about 45% of our listening, 30% speaking, 16% reading, and 9% writing (Hayes, 1991). However, most people are not entirely sure what the word “listening” is or how to do it effectively.

Hearing Is Not Listening

Hearing refers to a passive activity where an individual perceives sound by detecting vibrations through an ear. Hearing is a physiological process that is continuously happening. We are bombarded by sounds all the time. Unless you are in a sound-proof room or are 100% deaf, we are constantly hearing sounds. Even in a sound-proof room, other sounds that are normally not heard like a beating heart or breathing will become more apparent as a result of the blocked background noise.

Listening, on the other hand, is generally seen as an active process. Listening is “focused, concentrated attention for the purpose of understanding the meanings expressed by a [source]” (Wrench et al., 2017, p. 50). From this perspective, hearing is more of an automatic response when your ear perceives information; whereas, listening is what happens when we purposefully attend to different messages.

We can even take this a step further and differentiate normal listening from critical listening. Critical listening is the “careful, systematic thinking and reasoning to see whether a message makes sense in light of factual evidence” (Wrench et al., 2017, p. 61). From this perspective, it’s one thing to attend to someone’s message, but something very different to analyze what the person is saying based on known facts and evidence.

Let’s apply these ideas to a typical interpersonal situation. Let’s say that you and your best friend are having dinner at a crowded restaurant. Your ear is going to be attending to a lot of different messages all the time in that environment, but most of those messages get filtered out as “background noise,” or information we don’t listen to at all. Maybe then your favorite song comes on the speaker system the restaurant is playing, and you and your best friend both attend to the song because you both like it. A minute earlier, another song could have been playing, but you tuned it out (hearing) instead of taking a moment to enjoy and attend to the song itself (listen). Next, let’s say you and your friend get into a discussion about the issues of campus parking. Your friend states, “There’s never any parking on campus. What gives?” Now, if you’re critically listening to what your friend says, you’ll question the basis of this argument. For example, the word “never” in this statement is problematic because it would mean that the campus has zero available parking, which is probably not the case. Now, it may be difficult for your friend to find a parking spot on campus, but that doesn’t mean that there’s “never any parking.” In this case, you’ve gone from just listening to critically evaluating the argument your friend is making.

The Listening Process

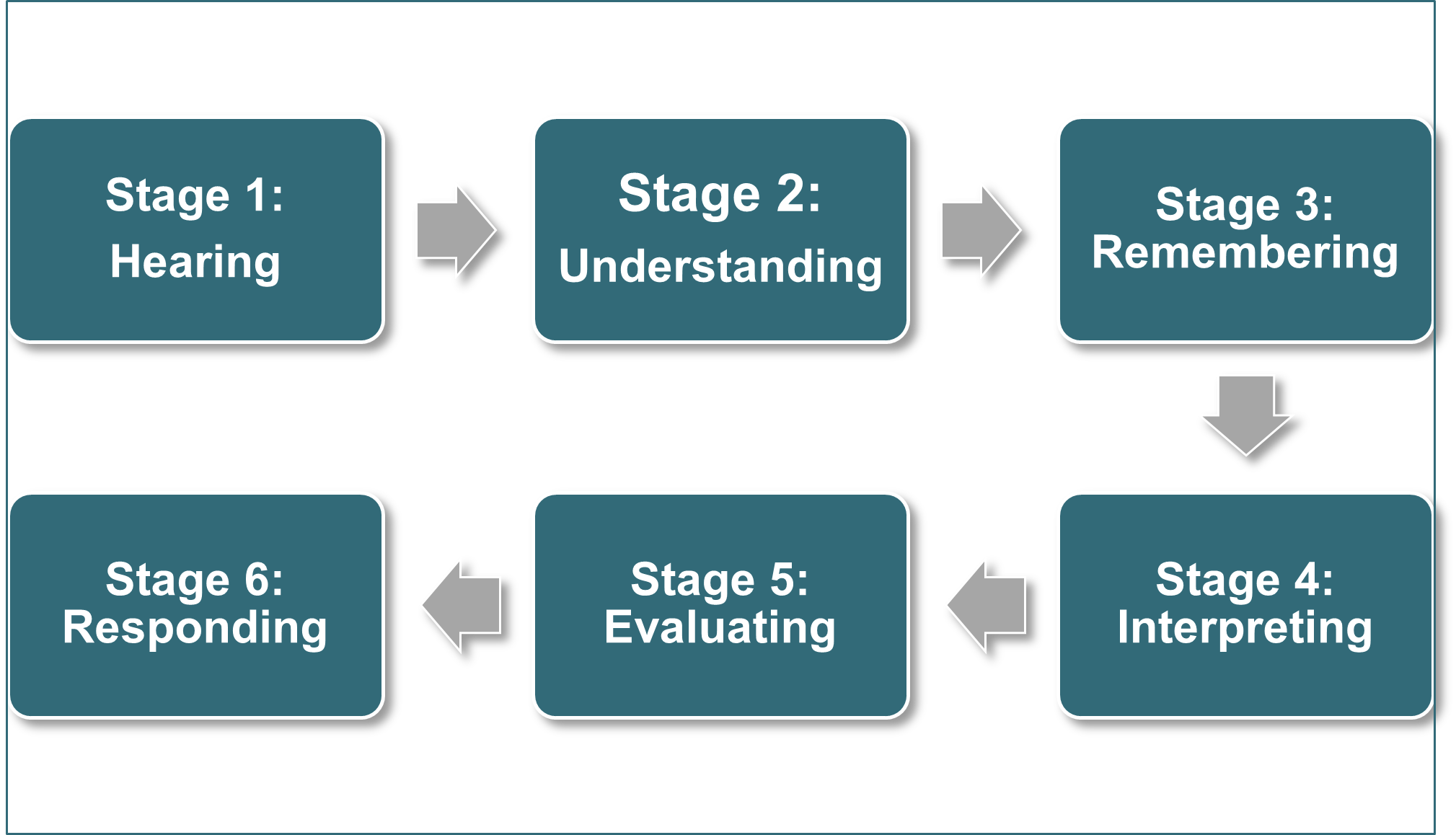

Judi Brownell (1985) created one of the most commonly used models for listening – the HURIER model. Although not the only model of listening that exists, we like this model because it breaks the process of hearing down into clearly differentiated stages: hearing, understanding, remembering, interpreting, evaluating, and responding (Figure 10.6)

Hearing

From a fundamental perspective, for listening to occur, an individual must attend to some kind of communicated message. Now, one can argue that hearing should not be equated with listening (as we did above), but it is the first step in the model of listening. Simply, if we don’t attend to the message at all, then communication never occurred from the receiver’s perspective. Now, to engage in mindful listening, it’s important to take hearing seriously because of the issue of intention. If we go into an interaction with another person without really intending to listening to what they have to say, we may end up being a passive listener who does nothing more than hear and nod our heads. Remember, mindful communication starts with the premise that we must think about our intentions and be aware of them.

Understanding

The second stage of the listening model is understanding, or the ability to comprehend or decode the source’s message. When we discussed the basic models of human communication, we discussed the idea of decoding a message. Decoding is when we attempt to break down the message we’ve heard into comprehensible meanings.

Remembering

Once we’ve decoded a message, we have to actually remember the message itself, or the ability to recall a message that was sent. We are bombarded by messages throughout our day, so it’s completely possible to attend to a message and decode it and then forget it minutes later.

Interpreting

The next stage in the HURIER model of listening is interpreting. According to Brownell (1985), “interpreting messages involves attention to all of the various speaker and contextual variables that provide a background for accurately perceived messages” (p. 43). So, what do we mean by contextual variables? A lot of the interpreting process is being aware of the nonverbal cues (both oral and physical) that accompany a message to accurately assign meaning to the message.

Imagine you’re having a conversation with one of your peers, and he says, “I love math.” Well, the text itself is demonstrating an overwhelming joy and calculating mathematical problems. However, if the message is accompanied by an eye roll or is said in a manner that makes it sound sarcastic, then the meaning of the oral phrase changes. Part of interpreting a message then is being sensitive to nonverbal cues.

Evaluating

The next stage is the evaluating stage, or judging the message itself. One of the biggest hurdles many people have with listening is the evaluative stage. Our personal biases, values, and beliefs can prevent us from effectively listening to someone else’s message.

Let’s imagine that you despise a specific politician. It’s gotten to the point where if you hear this politician’s voice, you immediately change the television channel. Even hearing other people talk about this politician causes you to tune out completely. In this case, your own bias against this politician prevents you from effectively listening to their message or even others’ messages involving this politician. Overcoming our own biases against the source of a message or the content of a message in an effort to truly listen to a message is not easy. One of the reasons listening is a difficult process is because of our inherent desire to evaluate people and ideas. When it comes to evaluating another person’s message during conflict, it’s important to remember to be mindful of our own potential biases.

Responding

It’s important to realize that effective listening starts with the ear and centers in the brain, and only then should someone provide feedback to the message itself. Often, people jump from hearing and understanding to responding, which can cause problems as they jump to conclusions that have arisen by truncated interpretation and evaluation.

Ultimately, how we respond to a source’s message will dictate how the rest of that interaction will progress. If we outright dismiss what someone is saying, we put up a roadblock that says, “I don’t want to hear anything else.” On the other hand, if we nod our heads and say, “tell me more,” then we are encouraging the speaker to continue the interaction. For effective communication to occur, it’s essential to consider how our responses will impact the other person and our relationship with that other person.

Overall, when it comes to being a mindful listener, it’s vital to remember COAL: curiosity, openness, acceptance, and love (Siegal, 2007). We need to go into our interactions with others and try to see things from their points of view. When we engage in COAL, we can listen mindfully and be in the moment.

Listening Styles

Now that we have a better understanding of how listening works, let’s talk about four different styles of listening researchers have identified. Kittie Watson, Larry Barker, and James Weaver (1995) defined listening styles as “attitudes, beliefs, and predispositions about the how, where, when, who, and what of the information reception and encoding process” (p. 2). Watson et al. (1992) identified four distinct listening styles: people, content, action, and time.

Self-assessment

See Appendix B: Self-Assessments

- Take the Listening Style Questionnaire.

The Four Listening Styles

People

The first listening style is the people-oriented listening style. People-oriented listeners tend to be more focused on the person sending the message than the content of the message. As such, people-oriented listeners focus on the emotional states of senders of information. One way to think about people-oriented listeners is to see them as highly compassionate, empathic, and sensitive, which allows them to put themselves in the shoes of the person sending the message.

People-oriented listeners often work well in helping professions where listening to the person and understanding their feelings is very important (e.g., therapist, counselor, social worker, etc.). People-oriented listeners are also very focused on maintaining relationships, so they are good at casual conservation where they can focus on the person.\

Action

The second listening style is the action-oriented listener. Action-oriented listeners are focused on what the source wants. The action-oriented listener wants a source to get to the point quickly. Instead of long, drawn-out lectures, the action-oriented speaker would prefer quick bullet points that get to what the source desires. Action-oriented listeners “tend to preference speakers that construct organized, direct, and logical presentations” (Bodie & Worthington, 2010, p. 71). When dealing with an action-oriented listener, it’s important to realize that they want you to be logical and get to the point. One of the things action-oriented listeners commonly do is search for errors and inconsistencies in someone’s message, so it’s important to be organized and have your facts straight.

Content

The third type of listener is the content-oriented listener, or a listener who focuses on the content of the message and process that message in a systematic way. Of the four different listening styles, content-oriented listeners are more adept at listening to complex information. Content-oriented listeners “believe it is important to listen fully to a speaker’s message prior to forming an opinion about it (while action listeners tend to become frustrated if the speaker is ‘wasting time’)” (Bodie & Worthington, 2010, p. 71). When it comes to analyzing messages, content-oriented listeners really want to dig into the message itself. They want as much information as possible in order to make the best evaluation of the message. As such, “they want to look at the time, the place, the people, the who, the what, the where, the when, the how … all of that. They don’t want to leave anything out” (Grant, n.d.)

Time

The final listening style is the time-oriented listening style. Time-oriented listeners are sometimes referred to as “clock watchers” because they’re always in a hurry and want a source of a message to speed things up a bit. Time-oriented listeners “tend to verbalize the limited amount of time they are willing or able to devote to listening and are likely to interrupt others and openly signal disinterest” (Bodie et al., 2013, p. 73). They often feel that they are overwhelmed by so many different tasks that need to be completed (whether real or not), so they usually try to accomplish multiple tasks while they are listening to a source. Of course, multitasking often leads to someone’s attention being divided, and information being missed.

Thinking About the Four Listening Types

Kina Mallard (1999) broke down the four listening styles and examined some of the common positive characteristics, negative characteristics, and strategies for communicating with the different listening styles. These ideas are summarized in the tables below.

Table 10.2 People-Oriented Listeners.

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with People-Oriented Listeners |

|---|---|---|

| Show care and concern for others | Over involved in feelings of others | Use stories and illustrations to make points |

| Are nonjudgmental | Avoid seeing faults in others | Use we rather than I in conversations |

| Provide clear verbal and nonverbal feedback signals | Internalize/adopt emotional states of others | Use emotional examples and appeals |

| Are interested in building relationships | Are overly expressive when giving feedback | Show some vulnerability when possible |

| Notice others moods quickly | Are nondiscriminating in building relationships | Use self-effacing humor or illustrations |

| Source: Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | ||

Table 10.3 Action-Oriented Listeners

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with Action-Oriented Listeners |

|---|---|---|

| Get to the point quickly | Tend to be impatient with rambling speakers | Keep main points to three or fewer |

| Give clear feedback concerning expectations | Jump ahead and reach conclusions quickly | Keep presentations short and concise |

| Concentrate on understanding task | Jump ahead or finishes thoughts of speakers | Have a step-by-step plan and label each step |

| Help others focus on whats important | Minimize relationship issues and concerns | Watch for cues of disinterest and pick up vocal pace at those points or change subjects |

| Encourage others to be organized and concise | Ask blunt questions and appear overly critical | Speak at a rapid but controlled rate |

| Source: Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | ||

Table 10.4 Content-Oriented Listeners

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with Content-Oriented Listeners |

|---|---|---|

| Value technical information | Are overly detail oriented | Use two-side arguments when possible |

| Test for clarity and understanding | May intimidate others by asking pointed questions | Provide hard data when available |

| Encourage others to provide support for their ideas | Minimize the value of nontechnical information | Quote credible experts |

| Welcome complex and challenging information | Discount information from nonexperts | Suggest logical sequences and plan |

| Look at all sides of an issue | Take a long time to make decisions | Use charts and graphs |

| Source: Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | ||

Table 10.5 Time-Oriented Listeners

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with Content-Oriented Listeners |

|---|---|---|

| Value technical information | Are overly detail oriented | Use two-side arguments when possible |

| Test for clarity and understanding | May intimidate others by asking pointed questions | Provide hard data when available |

| Encourage others to provide support for their ideas | Minimize the value of nontechnical information | Quote credible experts |

| Welcome complex and challenging information | Discount information from nonexperts | Suggest logical sequences and plan |

| Look at all sides of an issue | Take a long time to make decisions | Use charts and graphs |

| Source: Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | ||

We should mention that many people are not just one listening style or another. It’s possible to be a combination of different listening styles. However, some of the listening style combinations are more common. For example, someone who is action-oriented and time-oriented will want the bare-bones information so they can make a decision. On the other hand, it’s hard to be a people-oriented listener and time-oriented listener because being empathic and attending to someone’s feelings takes time and effort.

Types of Listening Responses

Who do you think is a great listener? Why did you name that particular person? How can you tell that person is a good listener? You probably recognize a good listener based on the nonverbal and verbal cues that they display. In this section, we will discuss different types of listening responses. We all don’t listen in the same way. Also, each situation is different and requires a distinct style that is appropriate for that situation.

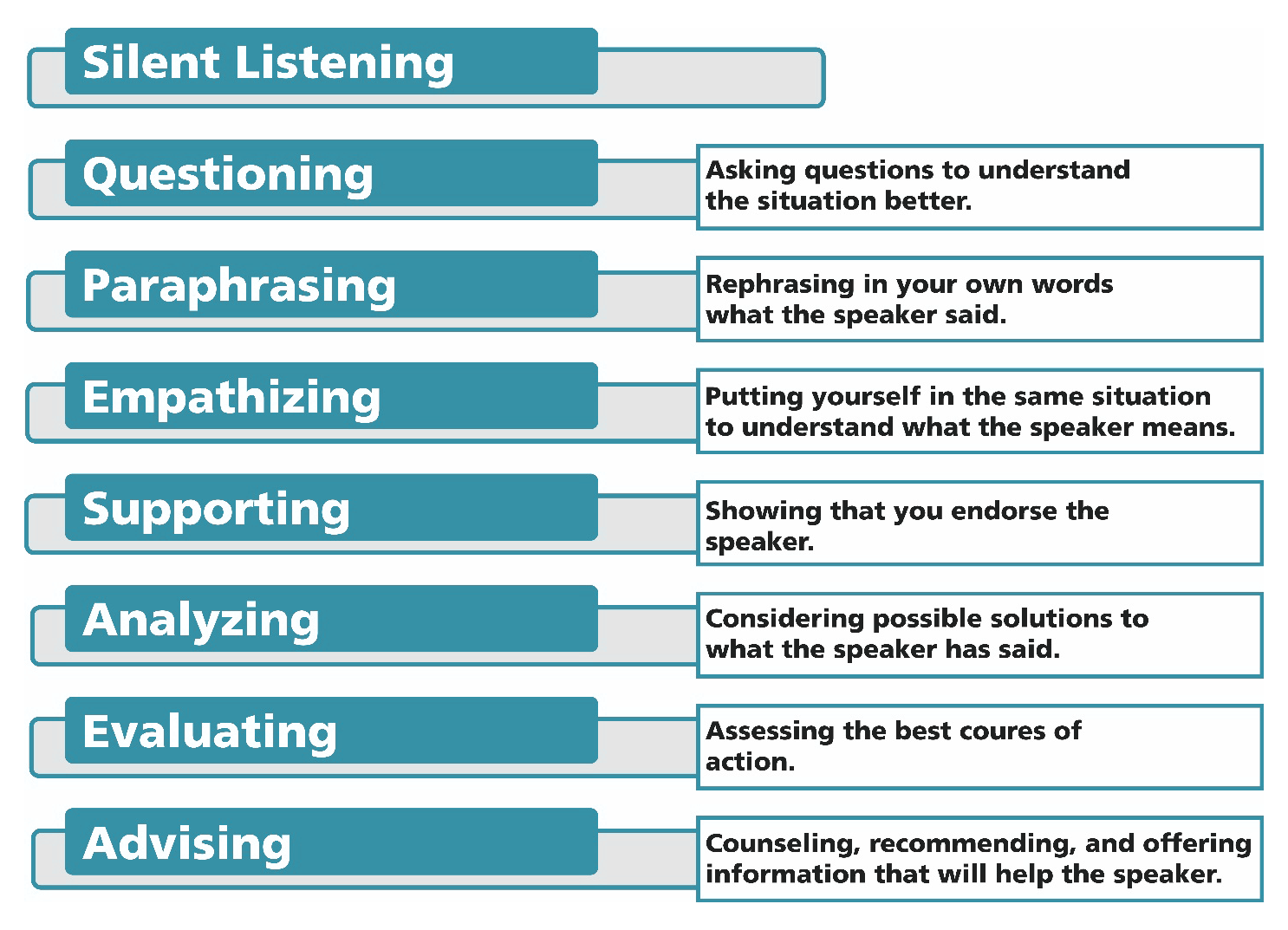

Ronald Adler, Lawrence Rosenfeld, and Russell Proctor (2013) are three interpersonal scholars who have done quite a bit with listening. Based on their research, they have found different types of listening responses: silent listening, questioning, paraphrasing, empathizing, supporting, analyzing, evaluating, and advising (Adler et al., 2013).

Silent Listening

Silent listening occurs when you say nothing. It is ideal in certain situations and awful in other situations. However, when used correctly, it can be very powerful. If misused, you could give the wrong impression to someone. It is appropriate to use when you don’t want to encourage more talking. It also shows that you are open to the speaker’s ideas. Sometimes people get angry when someone doesn’t respond. They might think that this person is not listening or trying to avoid the situation. But it might be due to the fact that the person is just trying to gather their thoughts, or perhaps it would be inappropriate to respond. There are certain situations such as in counseling, where silent listening can be beneficial because it can help that person figure out their feelings and emotions.

Questioning

In situations where you want to get answers, it might be beneficial to use questioning. You can do this in a variety of ways. There are several ways to question in a sincere, nondirective way including to clarify meaning; to learn about others’ thoughts, feelings and wants; to encourage elaboration; to encourage discovery; and to gather more facts and details.

Sincere questions are ones that are created to find a genuine answer. Counterfeit questions are disguised attempts to send a message, not to receive one. Sometimes, counterfeit questions can cause the listener to be defensive. For instance, if someone asks you, “Tell me how many times this week you arrived late to work?” The speaker implies that you were late several times, even though that has not been established. A speaker can use questions that make statements by emphasizing specific words or phrases, stating an opinion or feeling on the subject. They can ask questions that carry hidden agendas, like “Do you have $5?” because the person would like to borrow that money. Some questions seek “correct” answers. For instance, when a friend says, “Do you like my new glasses?” You probably have a correct or ideal answer. There are questions that are based on unchecked assumptions. An example would be, “Why aren’t you listening?” This example implies that the person wasn’t listening, when in fact they are listening.

Consider this: Open and Close Ended Questions

There is a general distinction made between Open Ended Question, questions that likely require some thought and/or more than a yes/no answer, and Close Ended Questions, questions that only require a specific answer and/or a yes/no answer. This is an important distinction to understand and remember. In the context of managing conflict open ended questions are utilized for Information Gathering and close ended questions are used for clarifying concepts or ideas you have heard. Here are examples of these types of questions.

There is a general distinction made between Open Ended Question, questions that likely require some thought and/or more than a yes/no answer, and Close Ended Questions, questions that only require a specific answer and/or a yes/no answer. This is an important distinction to understand and remember. In the context of managing conflict open ended questions are utilized for Information Gathering and close ended questions are used for clarifying concepts or ideas you have heard. Here are examples of these types of questions.

Close Ended Questions

- Is this what you said…?

- Did I hear you say…?

- Did I understand you when you said…?

- Did I hear you correctly when you said…?

- Did I paraphrase what you said correctly?

- So this took place on….?

- So you would like to see…?

Open Ended Questions

- If there was one small way that things could be better starting today, what would that be?

- How did you feel when…?

- How could you have handled it differently?

- When did it began?

- When did you first notice…?

- When did that happen?

- Where did it happen?

- What was that all about?

- What happened then?

- What would you like to do about it?

- I want to understand from your perspective, would you please tell me again?

- What do you think would make this better going forward?

- What criteria did you use to…?

- What’s another way you might…?

- What resources were used for the project?

- Tell me more about… (not a question, but an open ended prompt)

A type of question to watch out for is Leading Questions, which provides a direction or answer for someone to agree or disagree with. An example would be, “So you are going to vote for____ for prime minister, aren’t you?” or “What they did is unbelievably, don’t you agree?” These questions can easily be turned into information gathering questions, “Who are you going to vote for this year?” or “What do you this about their behavior?”

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is defined as restating in your own words, the message you think the speaker just sent. There are three types of paraphrasing. First, you can change the speaker’s wording to indicate what you think they meant. Second, you can offer an example of what you think the speaker is talking about. Third, you can reflect on the underlying theme of a speaker’s remarks. Paraphrasing represents mindful listening in the way that you are trying to analyze and understand the speaker’s information. Paraphrasing can be used to summarize facts and to gain consensus in essential discussions. This could be used in a business meeting to make sure that all details were discussed and agreed upon. Paraphrasing can also be used to understand personal information more accurately. Think about being in a counselor’s office. Counselors often paraphrase information to understand better exactly how you are feeling and to be able to analyze the information better.

Empathizing

Empathizing is used to show that you identify with a speaker’s information. You are not empathizing when you deny others the rights to their feelings. Examples of this are statements such as, “It’s really not a big deal” or “Who cares?” This indicates that the listener is trying to make the speaker feel a different way. In minimizing the significance of the situation, you are interpreting the situation in your perspective and passing judgment.

Supporting

Sometimes, in a discussion, people want to know how you feel about them instead of a reflection on the content. Several types of supportive responses are: agreement, offers to help, praise, reassurance, and diversion. The value of receiving support when faced with personal problems is very important. This has been shown to enhance psychological, physical, and relational health. To effectively support others, you must meet certain criteria. You have to make sure that your expression of support is sincere, be sure that other person can accept your support, and focus on “here and now” rather than “then and there.”

Analyzing

Analyzing is helpful in gaining different alternatives and perspectives by offering an interpretation of the speaker’s message. However, this can be problematic at times. Sometimes the speaker might not be able to understand your perspective or may become more confused by accepting it. To avoid this, steps must be taken in advance. These include tentatively offering your interpretation instead of as an absolute fact. By being more sensitive about it, it might be more comfortable for the speaker to accept. You can also make sure that your analysis has a reasonable chance of being correct. If it were inaccurate, it would leave the person more confused than before. Also, you must make sure the person will be receptive to your analysis and that your motive for offering is to truly help the other person. An analysis offered under any other circumstances is useless.

Evaluating

Evaluating appraises the speaker’s thoughts or behaviors. The evaluation can be favorable (“that makes sense”) or negative (passing judgment). Negative evaluations can be critical or non-critical (constructive criticism). Two conditions offer the best chance for evaluations to be received: if the person with the problem requested an evaluation, and if it is genuinely constructive and not designed as a putdown.

Advising

Advising differs from evaluations. It is not always the best solution and can sometimes be harmful. In order to avoid this, you must make sure four conditions are present: be sure the person is receptive to your suggestions, make sure they are truly ready to accept it, be confident in the correctness of your advice, and be sure the receiver won’t blame you if it doesn’t work out.

Barriers to Effective Listening

Barriers to effective listening are present at every stage of the listening process (Hargie, 2011). At the receiving stage, noise can block or distort incoming stimuli. At the interpreting stage, complex or abstract information may be difficult to relate to previous experiences, making it difficult to reach understanding. At the recalling stage, natural limits to our memory and challenges to concentration can interfere with remembering. At the evaluating stage, personal biases and prejudices can lead us to block people out or assume we know what they are going to say. At the responding stage, a lack of paraphrasing and questioning skills can lead to misunderstanding. In the following section, we will explore how environmental and physical factors, cognitive and personal factors, and bad listening practices present barriers to effective listening.

Environmental, Physical, and Psychological Barriers

Environmental noise, such as lighting, temperature, and furniture affect our ability to listen. A room that is too dark can make us sleepy, just as a room that is too warm or cool can raise awareness of our physical discomfort to a point that it is distracting. Some seating arrangements facilitate listening, while others separate people. In general, listening is easier when listeners can make direct eye contact with and are in close physical proximity to a speaker. The ability to effectively see and hear a person increases people’s confidence in their abilities to receive and process information. Eye contact and physical proximity can still be affected by noise. Environmental noises such as a whirring air conditioner, barking dogs, or a ringing fire alarm can obviously interfere with listening despite direct lines of sight and well-placed furniture.

Physiological noise, like environmental noise, can interfere with our ability to process incoming information. This is considered a physical barrier to effective listening because it emanates from our physical body. Physiological noise is noise stemming from a physical illness, injury, or bodily stress. Ailments such as a cold, a broken leg, a headache, or a poison ivy outbreak can range from annoying to unbearably painful and impact our listening relative to their intensity. Another type of noise, psychological noise, bridges physical and cognitive barriers to effective listening. Psychological noise, or noise stemming from our psychological states including moods and level of arousal, can facilitate or impede listening. Any mood or state of arousal, positive or negative, that is too far above or below our regular baseline creates a barrier to message reception and processing. The generally positive emotional state of being in love can be just as much of a barrier as feeling hatred. Excited arousal can also distract as much as anxious arousal. Stress about an upcoming events ranging from losing a job, to having surgery, to wondering about what to eat for lunch can overshadow incoming messages. Cognitive limits, a lack of listening preparation, difficult or disorganized messages, and prejudices can also interfere with listening. Whether you call it multitasking, daydreaming, glazing over, or drifting off, we all cognitively process other things while receiving messages.

Difference Between Speech and Thought Rate

Our ability to process more information than what comes from one speaker or source creates a barrier to effective listening. While people speak at a rate of 125 to 175 words per minute, we can process between 400 and 800 words per minute (Hargie, 2011). This gap between speech rate and thought rate gives us an opportunity to side-process any number of thoughts that can be distracting from a more important message. Because of this gap, it is impossible to give one message our “undivided attention,” but we can occupy other channels in our minds with thoughts related to the central message. For example, using some of your extra cognitive processing abilities to repeat, rephrase, or reorganize messages coming from one source allows you to use that extra capacity in a way that reinforces the primary message.

The difference between speech and thought rate connects to personal barriers to listening, as personal concerns are often the focus of competing thoughts that can take us away from listening and challenge our ability to concentrate on others’ messages. Two common barriers to concentration are self-centeredness and lack of motivation (Brownell, 1993). For example, when our self-consciousness is raised, we may be too busy thinking about how we look, how we’re sitting, or what others think of us to be attentive to an incoming message. Additionally, we are often challenged when presented with messages that we do not find personally relevant. In general, we employ selective attention, which refers to our tendency to pay attention to the messages that benefit us in some way and filter others out.

Another common barrier to effective listening that stems from the speech and thought rate divide is response preparation. Response preparation refers to our tendency to rehearse what we are going to say next while a speaker is still talking. Rehearsal of what we will say once a speaker’s turn is over is an important part of the listening process that takes place between the recalling and evaluation and/or the evaluation and responding stage. Rehearsal becomes problematic when response preparation begins as someone is receiving a message and hasn’t had time to engage in interpretation or recall. In this sense, we are listening with the goal of responding instead of with the goal of understanding, which can lead us to miss important information that could influence our response.

Lack of Skill

Another barrier to effective listening is a general lack of listening preparation. Unfortunately, most people have never received any formal training or instruction related to listening. Although some people think listening skills just develop over time, competent listening is difficult, and enhancing listening skills takes concerted effort. Even when listening education is available, people do not embrace it as readily as they do opportunities to enhance their speaking skills. Listening is often viewed as an annoyance or a chore, or just ignored or minimized as part of the communication process. In addition, our individualistic society values speaking more than listening, as it’s the speakers who are sometimes literally in the spotlight. Although listening competence is a crucial part of social interaction and many of us value others we perceive to be “good listeners,” listening just doesn’t get the same kind of praise, attention, instruction, or credibility as speaking. Teachers, parents, and relational partners explicitly convey the importance of listening through statements like “You better listen to me,” “Listen closely,” and “Listen up,” but these demands are rarely paired with concrete instruction.

Bad messages and/or lack of communication skill on the part of the speaker also presents a barrier to effective listening. Sometimes our trouble listening originates in the sender. In terms of message construction, poorly structured messages or messages that are too vague, too jargon filled, or too simple can present listening difficulties. In terms of speakers’ delivery, verbal fillers, monotone voices, distracting movements, or a disheveled appearance can inhibit our ability to cognitively process a message (Hargie, 2011). Listening also becomes difficult when a speaker tries to present too much information. Information overload is a common barrier to effective listening that good speakers can help mitigate by building redundancy into their speeches and providing concrete examples of new information to help audience members interpret and understand the key ideas.

Prejudice

Oscar Wilde said, “Listening is a very dangerous thing. If one listens one may be convinced.” Unfortunately, some of our default ways of processing information and perceiving others lead us to rigid ways of thinking. When we engage in prejudiced listening, we are usually trying to preserve our ways of thinking and avoid being convinced of something different. This type of prejudice is a barrier to effective listening, because when we prejudge a person based on his or her identity or ideas, we usually stop listening in an active and/or ethical way.

We exhibit prejudice in our listening in several ways, some of which are more obvious than others. For example, we may claim to be in a hurry and only selectively address the parts of a message that we agree with or that aren’t controversial. We can also operate from a state of denial where we avoid a subject or person altogether so that our views are not challenged. Prejudices that are based on a person’s identity, such as race, age, occupation, or appearance, may lead us to assume that we know what they will say, essentially closing down the listening process. Keeping an open mind and engaging in perception checking can help us identify prejudiced listening and hopefully shift into more competent listening practices.

Inattentional Blindness

Do you regularly spot editing errors in movies? Can you multitask effectively, texting while talking with your friends or watching television? Are you fully aware of your surroundings? If you answered yes to any of those questions, you’re not alone. And, you’re most likely wrong.

More than 50 years ago, experimental psychologists began documenting the many ways that our perception of the world is limited, not by our eyes and ears, but by our minds. We appear able to process only one stream of information at a time, effectively filtering other information from awareness. To a large extent, we perceive only that which receives the focus of our cognitive efforts: our attention.

Imagine the following task, known as dichotic listening (e.g., Cherry, 1953; Moray, 1959; Treisman, 1960): You put on a set of headphones that play two completely different speech streams, one to your left ear and one to your right ear. Your task is to repeat each syllable spoken into your left ear as quickly and accurately as possible, mimicking each sound as you hear it. When performing this attention-demanding task, you won’t notice if the speaker in your right ear switches to a different language or is replaced by a different speaker with a similar voice. You won’t notice if the content of their speech becomes nonsensical. In effect, you are deaf to the substance of the ignored speech. But, that is not because of the limits of your auditory senses. It is a form of cognitive deafness, due to the nature of focused, selective attention. Even if the speaker on your right headphone says your name, you will notice it only about one-third of the time (Conway et al., 2001). And, at least by some accounts, you only notice it that often because you still devote some of your limited attention to the ignored speech stream (Cherry, 1953). In this task, you will tend to notice only large physical changes (e.g., a switch from a male to a female speaker), but not substantive ones, except in rare cases.

This selective listing task highlights the power of attention to filter extraneous information from awareness while letting in only those elements of our world that we want to hear. Focused attention is crucial to our powers of observation, making it possible for us to zero in on what we want to see or hear while filtering out irrelevant distractions. But, it has consequences as well: We can miss what would otherwise be obvious and important signals.

Bad Listening Practices

The previously discussed barriers to effective listening may be difficult to overcome because they are at least partially beyond our control. Physical barriers, cognitive limitations, and perceptual biases exist within all of us, and it is more realistic to believe that we can become more conscious of and lessen them than it is to believe that we can eliminate them altogether. Other “bad listening” practices may be habitual, but they are easier to address with some concerted effort. These bad listening practices include interrupting, distorted listening, eavesdropping, aggressive listening, narcissistic listening, and pseudo-listening.

Interrupting

Conversations unfold as a series of turns, and turn taking is negotiated through a complex set of verbal and nonverbal signals that are consciously and subconsciously received. In this sense, conversational turn taking has been likened to a dance where communicators try to avoid stepping on each other’s toes. One of the most frequent glitches in the turn-taking process is interruption, but not all interruptions are considered “bad listening.” An interruption could be unintentional if we misread cues and think a person is done speaking only to have they start up again at the same time we do. Sometimes interruptions are more like overlapping statements that show support (e.g., “I think so too.”) or excitement about the conversation (e.g., “That’s so cool!”). Back-channel cues like “uh-huh,” as we learned earlier, also overlap with a speaker’s message. We may also interrupt out of necessity if we’re engaged in a task with the other person and need to offer directions (e.g., “Turn left here.”), instructions (e.g., “Will you stir the sauce?”), or warnings (e.g., “Look out behind you!”). All these interruptions are not typically thought of as evidence of bad listening unless they become distracting for the speaker or are unnecessary.

Unintentional interruptions can still be considered bad listening if they result from mindless communication. As we’ve already learned, intended meaning is not as important as the meaning that is generated in the interaction itself. So if you interrupt unintentionally, but because you were only half-listening, then the interruption is still evidence of bad listening. The speaker may form a negative impression of you that can’t just be erased by you noting that you didn’t “mean to interrupt.” Interruptions can also be used as an attempt to dominate a conversation. A person engaging in this type of interruption may lead the other communicator to try to assert dominance, too, resulting in a competition to see who can hold the floor the longest or the most often. More than likely, though, the speaker will form a negative impression of the interrupter and may withdraw from the conversation.

Distorted Listening

Distorted listening occurs in many ways. Sometimes we just get the order of information wrong, which can have relatively little negative effects if we are casually recounting a story, annoying effects if we forget the order of turns (left, right, left or right, left, right?) in our driving directions, or very negative effects if we recount the events of a crime out of order, which leads to faulty testimony at a criminal trial. Rationalization is another form of distorted listening through which we adapt, edit, or skew incoming information to fit our existing schemata. We may, for example, reattribute the cause of something to better suit our own beliefs. Sometimes we actually change the words we hear to make them better fit what we are thinking. This can easily happen if we join a conversation late, overhear part of a conversation, or are being a lazy listener and miss important setup and context. Passing along distorted information can lead to negative consequences ranging from starting a false rumor about someone to passing along incorrect medical instructions from one health-care provider to the next (Hargie, 2011). Last, the addition of material to a message is a type of distorted listening that actually goes against our normal pattern of listening, which involves reducing the amount of information and losing some meaning as we take it in. The metaphor of “weaving a tall tale” is related to the practice of distorting through addition, as inaccurate or fabricated information is added to what was actually heard. Addition of material is also a common feature of gossip.

Eavesdropping

Eavesdropping is a bad listening practice that involves a calculated and planned attempt to secretly listen to a conversation. There is a difference between eavesdropping on and overhearing a conversation. Many if not most of the interactions we have throughout the day occur in the presence of other people. However, given that our perceptual fields are usually focused on the interaction, we are often unaware of the other people around us or don’t think about the fact that they could be listening in on our conversation. We usually only become aware of the fact that other people could be listening in when we’re discussing something private.

People eavesdrop for a variety of reasons. People might think another person is talking about them behind their back or that someone is engaged in illegal or unethical behavior. Sometimes people eavesdrop to feed the gossip mill or out of curiosity (McCornack, 2007). In any case, this type of listening is considered bad because it is a violation of people’s privacy. Consequences for eavesdropping may include an angry reaction if caught, damage to interpersonal relationships, or being perceived as dishonest and sneaky. Additionally, eavesdropping may lead people to find out information that is personally upsetting or hurtful, especially if the point of the eavesdropping is to find out what people are saying behind their back.

Aggressive Listening

Aggressive listening is a bad listening practice in which people pay attention in order to attack something that a speaker says (McCornack, 2007). Aggressive listeners like to ambush speakers in order to critique their ideas, personality, or other characteristics. Such behavior often results from built-up frustration within an interpersonal relationship. Unfortunately, the more two people know each other, the better they will be at aggressive listening. Take the following exchange between long-term partners:

Deb: I’ve been thinking about making a salsa garden next to the side porch. I think it would be really good to be able to go pick our own tomatoes and peppers and cilantro to make homemade salsa.

Summer: Really? When are you thinking about doing it?

Deb: Next weekend. Would you like to help?

Summer: I won’t hold my breath. Every time you come up with some “idea of the week” you get so excited about it. But do you ever follow through with it? No. We’ll be eating salsa from the store next year, just like we are now.

Although Summer’s initial response to Deb’s idea is seemingly appropriate and positive, she asks the question because she has already planned her upcoming aggressive response. Summer’s aggression toward Deb isn’t about a salsa garden; it’s about a building frustration with what Summer perceives as Deb’s lack of follow-through on her ideas. Aside from engaging in aggressive listening because of built-up frustration, such listeners may also attack others’ ideas or mock their feelings because of their own low self-esteem and insecurities.

Narcissistic Listening

Narcissistic listening is a form of self-centered and self-absorbed listening in which listeners try to make the interaction about them (McCornack, 2007). Narcissistic listeners redirect the focus of the conversation to them by interrupting or changing the topic. When the focus is taken off them, narcissistic listeners may give negative feedback by pouting, providing negative criticism of the speaker or topic, or ignoring the speaker. A common sign of narcissistic listening is the combination of a “pivot,” when listeners shift the focus of attention back to them, and “one-upping,” when listeners try to top what previous speakers have said during the interaction. You can see this narcissistic combination in the following interaction:

Bryce: My boss has been really unfair to me lately and hasn’t been letting me work around my class schedule. I think I may have to quit, but I don’t know where I’ll find another job.

Toby: Why are you complaining? I’ve been working with the same stupid boss for two years. He doesn’t even care that I’m trying to get my degree and work at the same time. And you should hear the way he talks to me in front of the other employees.

Narcissistic listeners, given their self-centeredness, may actually fool themselves into thinking that they are listening and actively contributing to a conversation. We all have the urge to share our own stories during interactions, because other people’s communication triggers our own memories about related experiences. It is generally more competent to withhold sharing our stories until the other person has been able to speak and we have given the appropriate support and response. But we all shift the focus of a conversation back to us occasionally, either because we don’t know another way to respond or because we are making an attempt at empathy. Narcissistic listeners consistently interrupt or follow another speaker with statements like “That reminds me of the time…,” “Well, if I were you…,” and “That’s nothing…” (Nichols, 1995). As we’ll learn later, matching stories isn’t considered empathetic listening, but occasionally doing it doesn’t make you a narcissistic listener.

Pseudo-listening

Do you have a friend or family member who repeats stories? If so, then you’ve probably engaged in pseudo-listening as a politeness strategy. Pseudo-listening is behaving as if you’re paying attention to a speaker when you’re actually not (McCornack, 2007). Outwardly visible signals of attentiveness are an important part of the listening process, but when they are just an “act,” the pseudo-listener is engaging in bad listening behaviors. The listener is not actually going through the stages of the listening process and will likely not be able to recall the speaker’s message or offer a competent and relevant response. Although it is a bad listening practice, we all understandably engage in pseudo-listening from time to time. If a friend needs someone to talk but you’re really tired or experiencing some other barrier to effective listening, it may be worth engaging in pseudo-listening as a relational maintenance strategy, especially if the friend just needs a sounding board and isn’t expecting advice or guidance. We may also pseudo-listen to a romantic partner or grandfather’s story for the fifteenth time to prevent hurting their feelings. We should avoid pseudo-listening when possible and should definitely avoid making it a listening habit. Although we may get away with it in some situations, each time we risk being “found out,” which could have negative relational consequences.

Active Listening

Active listening refers to the process of pairing outwardly visible positive listening behaviors with positive cognitive listening practices. Active listening can help address many of the environmental, physical, cognitive, and personal barriers to effective listening that we discussed earlier. The behaviors associated with active listening can also enhance informational, critical, and empathetic listening.

Being an active listener starts before you actually start receiving a message. Active listeners make strategic choices and take action in order to set up ideal listening conditions. Physical and environmental noises can often be managed by moving locations or by manipulating the lighting, temperature, or furniture. When possible, avoid important listening activities during times of distracting psychological or physiological noise. For example, we often know when we’re going to be hungry, full, more awake, less awake, more anxious, or less anxious, and advance planning can alleviate the presence of these barriers. Of course, we don’t always have control over our schedule, in which case we will need to utilize other effective listening strategies that we will learn more about later in this chapter.

In terms of cognitive barriers to effective listening, we can prime ourselves to listen by analyzing a listening situation before it begins. For example, you could ask yourself the following questions:

- “What are my goals for listening to this message?”

- “How does this message relate to me / affect my life?”

- “What listening type and style are most appropriate for this message?”

As we learned earlier, the difference between speech and thought processing rate means listeners’ level of attention varies while receiving a message. Effective listeners must work to maintain focus as much as possible and refocus when attention shifts or fades (Wolvin & Coakley, 1993). One way to do this is to find the motivation to listen. If you can identify intrinsic and or extrinsic motivations for listening to a particular message, then you will be more likely to remember the information presented. Ask yourself how a message could impact your life, your career, your intellect, or your relationships. This can help overcome our tendency toward selective attention. As senders of messages, we can help listeners by making the relevance of what we’re saying clear and offering well-organized messages that are tailored for our listeners.

Improving Listening

Many people admit that they could stand to improve their listening skills. This section will help us do that. In this section, we will learn strategies for developing and improving competence at each stage of the listening process. We will also define active listening and the behaviors that go along with it.

We can develop competence within each stage of the listening process (Ridge, 1993)

To improve listening at the hearing and understanding stages:

- prepare yourself to listen,

- discern between intentional messages and noise,

- concentrate on stimuli most relevant to your listening purpose(s) or goal(s),

- be mindful of the selection and attention process as much as possible,

- avoid interrupting someone while they are speaking in order to maintain your ability

- to receive stimuli and listen, and,

- pay attention so you can follow the conversational flow.

To improve listening at the remembering stage:

- use multiple sensory channels to decode messages and make more complete memories;

- repeat, rephrase, and reorganize information to fit your cognitive preferences; and

- use mnemonic devices as a gimmick to help with recall.

To improve listening at the interpreting stage,

- identify main points and supporting points;

- use contextual clues from the person or environment to discern additional meaning;

- be aware of how a relational, cultural, or situational context can influence meaning;

- be aware of the different meanings of silence; and

- note differences in tone of voice and other paralinguistic cues that influence meaning.

To improve listening at the evaluating stage,

- separate facts, inferences, and judgments;

- be familiar with and able to identify persuasive strategies and fallacies of reasoning;

- assess the credibility of the speaker and the message; and

- be aware of your own biases and how your perceptual filters can create barriers to effective listening.

To improve listening at the responding stage,

- reflect information to check understanding,

- ask appropriate clarifying and follow-up questions,

- give feedback that is relevant to the speaker’s purpose/motivation for speaking,

- adapt your response to the speaker and the context, and

- do not let the preparation and rehearsal of your response diminish earlier stages of listening.

Active Listening and Conflict

Active listening is challenging in calm everyday setting and it’s often even harder in times of conflict. When your brain is under the stress of conflict, it is extremely challenging to actively listen to what someone else is saying, because in a conflict situation you likely disagree with everything that is coming out of their mouth. In conflict is where the barriers to listening happen the most.

Think back to the idea of inattentional blindness. How do you think that impacts you in a conflict? Have you ever thought back to a high conflict situation and realized that you missed a key piece of information that was shared? Likely because in the heat of the moment you were too focused on either getting your point across, making your case, or figuring out how to make this conflict end. Inattentional blindness in conflict means that we are likely to miss key pieces of information, verbal or nonverbal. The more effort a cognitive task requires the more likely it becomes that you’ll miss noticing something significant. This in and of itself can lead to more conflict.

Or what about the difference between the speech and thought rate? You can process information at significantly higher rate than someone can share with you. In a conflict situation, you can process every previous conversation or conflict you have had with this person and still “hear” what they said. But you aren’t really listening when that is happening.

So what can you do about these challenges in a conflict situation? First, recognize that we are all wired to be distracted AND that you will likely miss something. Second, maximize the attention you do have available by avoiding distractions. The ring of a new call or the ding of a new text are hard to resist, so make it impossible to succumb to the temptation by turning your phone off or putting it somewhere out of reach. Third, don’t be afraid to slow down and pause a conversation because you were actively listening to someone. You build stronger relationships by showing people that you are truly listening to them and will give the hard conversations they time they deserve.

Adapted Works

“Talking and Listening” in Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Barriers to Effective Listening” in Communication in the Real World by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Listening” in A Primer on Communication Studies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

“Why aren’t they listening to me? Listening as a superpower and other important skills” in Making Conflict Suck Less: The Basics by Ashley Orme Nichols is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

Adler, R., Rosenfeld, L. B., & Proctor II, R. F. (2013). Interplay: The process of interpersonal communication. Oxford.

Bodie, G., & Worthington, D. (2010). Revisiting the Listening Styles Profile (LSP-16): A confirmatory factor analytic approach to scale validation and reliability estimation. International Journal of Listening, 24(2), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10904011003744516

Bodie, G. D., Worthington, D. L., & Gearhart, C. C. (2013). The Listening Styles Profile-Revised (LSP-R): A scale revision and evidence for validity. Communication Quarterly, 61(1), 72–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2012.720343

Brownell, J. (1985). A model for listening instruction: Management applications. The Bulletin of the Association for Business Communication, 48(3), 39-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/108056998504800312

Brownell, J., (1993). Listening environment: A perspective,” In Andrew D. Wolvin and Carolyn Gwynn Coakley (Eds.) Perspectives on Listening. Alex Publishing Corporation.

Cherry, E. C. (1953). Experiments on the recognition of speech with one and two ears. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 25, 975–979.

Conway, A. R. A., Cowan, N., & Bunting, M. F. (2001). The cocktail party phenomenon revisited: The importance of working memory capacity. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 8, 331–335.

Grant, K. (n.d.). Being aware of listening styles used in communication reduces your stress levels. https://www.kingsleygrant.com/knowing-listening-styles-reduces-stress/

Hayes, J. (1991). Interpersonal skills: Goal-directed behaviour at work. Routledge.

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice. Routledge.

Mallard, K. S. (1999). Lending an ear: The chair’s role as listener. The Department Chair, 9(3), 1-13.

Moray, N. (1959). Attention in dichotic listening: Affective cues and the influence of instructions. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 11, 56–60.

McCornack, S. (2007). Reflect and relate: An introduction to interpersonal communication. Bedford/St Martin’s.

Nichols, M. P. (1995). The lost art of listening. Guilford Press.

Ridge, A. (1993). A perspective of listening skills. In A. D. Wolvin, & C. G. Coakley (Eds.), Perspectives on listening. Alex Publishing Corporation.

Treisman, A. (1960). Contextual cues in selective listening. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12, 242–248.

Watson, K. W., Barker, L. L., & Weaver, J. B., III. (1992, March). Development and validation of the Listener Preference Profile [Paper Presentation]. The International Listening Association, Seattle, Washington.

Watson, K. W., Barker, L. L., & Weaver, J. B., III. (1995). The listening styles profile (LSP-16): Development and validation of an instrument to assess four listening styles. International Journal of Listening, 9, 1–13.

Wolvin, A. D., & Coakley, C. G. (1993). A listening taxonomy. In A. D. Wolvin, & C. G. Coakley (Eds.) Perspectives on Listening. Alex Publishing Corporation.

Wrench, J. S., Goding, A., Johnson, D. I., & Attias, B. A. (2017). Stand up, speak out: The practice and ethics of public speaking (Version 2). Flat World Knowledge.