7.3 Stress at Work

In this section:

Stress at Work

Our definition of stress points to a poor fit between individuals and their environments. Either excessive demands are being made, or reasonable demands are being made that individuals are ill-equipped to handle. Under stress, individuals are unable to respond to environmental stimuli without undue psychological and/or physiological damage, such as chronic fatigue, tension, or high blood pressure. This damage resulting from experienced stress is usually referred to as strain.

Before we examine the concept of work-related stress in detail, several important points need to be made. First, stress is pervasive in the work environment (McGrath, 1976). Most of us experience stress at some time. For instance, a job may require too much or too little from us. In fact, almost any aspect of the work environment is capable of producing stress. Stress can result from excessive noise, light, or heat; too much or too little responsibility; too much or too little work to accomplish; or too much or too little supervision.

Second, it is important to note that all people do not react in the same way to stressful situations, even in the same occupation. One individual (a high-need achiever) may thrive on a certain amount of job-related tension; this tension may serve to activate the achievement motive. A second individual may respond to this tension by worrying about her inability to cope with the situation. Thus, it is important that we recognize the central role of individual differences in the determination of experienced stress.

Often the key reason for the different reactions is a function of the different interpretations of a given event that different people make, especially concerning possible or probable consequences associated with the event. For example, the same report is required of student A and student B on the same day. Student A interprets the report in a very stressful way and imagines all the negative consequences of submitting a poor report. Student B interprets the report differently and sees it as an opportunity to demonstrate the things she has learned and imagines the positive consequences of turning in a high-quality report. Although both students face essentially the same event, they interpret and react to it differently.

Third, all stress is not necessarily bad. Although highly stressful situations invariably have dysfunctional consequences, moderate levels of stress often serve useful purposes. A moderate amount of job-related tension not only keeps us alert to environmental stimuli (possible dangers and opportunities), but in addition often provides a useful motivational function. Some experts argue that the best and most satisfying work that employees do is work performed under moderate stress. Some stress may be necessary for psychological growth, creative activities, and the acquisition of new skills. Learning to drive a car or play a piano or run a particular machine typically creates tension that is instrumental in skill development. It is only when the level of stress increases or when stress is prolonged that physical or psychological problems emerge.

Types of Stress at Work: Frustration and Anxiety

Two common types of stress in the workplace are frustration and anxiety. Frustration refers to a psychological reaction to an obstruction or impediment to goal-oriented behavior. Frustration occurs when an individual wishes to pursue a certain course of action but is prevented from doing so. This obstruction may be externally or internally caused. Examples of people experiencing obstacles that lead to frustration include a salesperson who continually fails to make a sale, a machine operator who cannot keep pace with the machine, or even a person dealing with a team member who is not contributing to the group.

Whereas frustration is a reaction to an obstruction in instrumental activities or behavior, anxiety is a feeling of inability to deal with anticipated harm. Anxiety occurs when people do not have appropriate responses or plans for coping with anticipated problems. It is characterized by a sense of dread, a foreboding, and a persistent apprehension of the future for reasons that are sometimes unknown to the individual.

What causes anxiety in work organizations? Hamner and Organ (1979) suggest several factors:

“Differences in power in organizations which leave people with a feeling of vulnerability to administrative decisions adversely affecting them; frequent changes in organizations, which make existing behavior plans obsolete; competition, which creates the inevitability that some persons lose ‘face,’ esteem, and status; and job ambiguity (especially when it is coupled with pressure). To these may be added some related factors, such as lack of job feedback, volatility in the organization’s economic environment, job insecurity, and high visibility of one’s performance (successes as well as failures). Obviously, personal, nonorganizational factors come into play as well, such as physical illness, problems at home, unrealistically high personal goals, and estrangement from one’s colleagues or one’s peer group” (p. 202).

A Model of Stress at Work

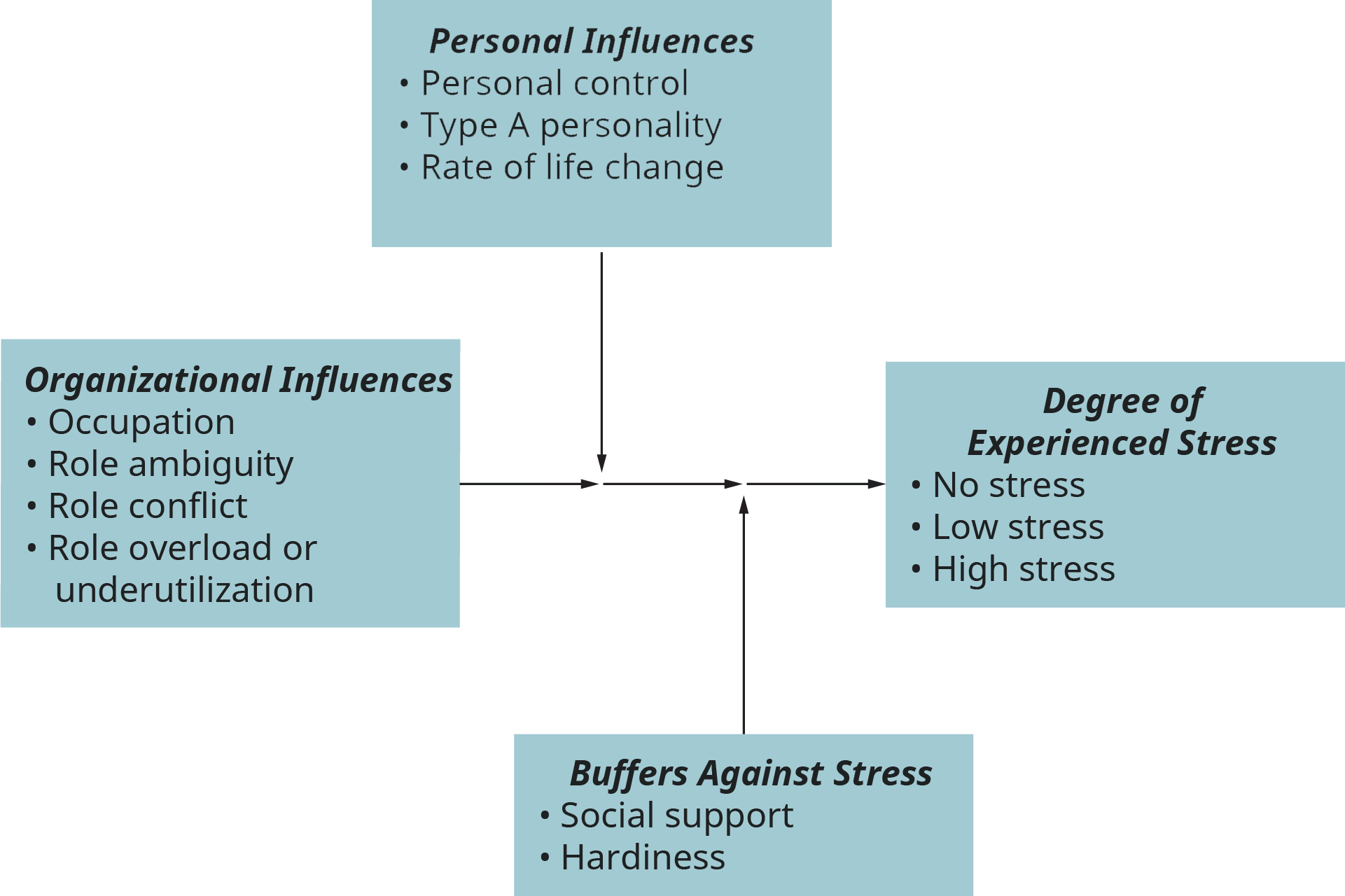

We will now consider several factors that have been found to influence both frustration and anxiety; we will present a general model of stress, including its major causes and its outcomes. Following this, we will explore several mechanisms by which employees and their managers cope with or reduce experienced stress in organizations. The model presented here draws heavily on the work of several social psychologists at the Institute for Social Research of the University of Michigan, including John French, Robert Caplan, Robert Kahn, and Daniel Katz. In essence, the proposed model identifies two major sources of stress: organizational sources and individual sources. In addition, the moderating effects of social support and hardiness are considered. These factors contribute to the degrees of experienced stress. These influences are shown in the figure below.

We begin with organizational influences on stress. Although many factors in the work environment have been found to influence the extent to which people experience stress on the job, four factors have been shown to be particularly strong. These are occupational differences, role ambiguity, role conflict, and role overload and underutilization. We will consider each of these factors in turn.

Organizational Influences on Stress

Occupational Differences

Tension and job stress are prevalent in our contemporary society and can be found in a wide variety of jobs. Consider, for example, the following quotes from interviews with working people. The first is from a bus driver:

“You have your tension. Sometimes you come close to having an accident, that upsets you. You just escape maybe by a hair or so. Sometimes maybe you get a disgruntled passenger on there who starts a big argument. Traffic. You have someone who cuts you off or stops in front of the bus. There’s a lot of tension behind that. . . . Most of the time you have to drive for the other drivers, to avoid hitting them. So, you take the tension home with you. Most of the drivers, they’ll suffer from hemorrhoids, kidney trouble, and such as that. I had a case of ulcers behind it” (Terkel, 1972, p. 275).

Or consider the plight of a bank teller:

“Some days, when you’re aggravated about something, you carry it after you leave the job. Certain people are bad days. (Laughs.) The type of person who will walk in and say, ‘My car’s double-parked outside. Would you hurry up, lady?’ . . . you want to say, ‘Hey, why did you double-park your car? So now you’re going to blame me if you get a ticket, ’cause you were dumb enough to leave it there?’ But you can’t. That’s the one hassle. You can’t say anything back. The customer’s always right” (Terkel, 1972, p. 348).

Stress is experienced by workers in many jobs: administrative assistants, assembly-line workers, servers and managers. In fact, it is difficult to find jobs that are without some degree of stress. We seldom talk about jobs without stress; instead, we talk about the degree or magnitude of the stress.

The work roles that people fill have a substantial influence on the degree to which they experience stress (Cooper & Payne, 1978; Hall & Savery, 1986). These differences do not follow the traditional blue-collar/white-collar dichotomy, however. In general, available evidence suggests that high-stress occupations are those in which incumbents have little control over their jobs, work under relentless time pressures or threatening physical conditions, or have major responsibilities for either human or financial resources.

A study by Kranz (1988) attempted to identify those occupations that were most (and least) stressful. The study results are presented in the table below. As shown, high-stress occupations (firefighter, race car driver, and astronaut) are typified by the stress-producing characteristics noted above, whereas low-stress occupations (musical instrument repairperson, medical records technician, and librarian) are not. It can therefore be concluded that a major source of general stress emerges from the occupation at which one is working.

Table 7.6 The Most and Least Stressful Jobs

| High-Stress Jobs | Low-Stress Jobs |

|---|---|

| 1. Firefighter | 1. Musical instrument repairperson |

| 2. Race car driver | 2. Industrial machine repairperson |

| 3. Astronaut | 3. Medical records technician |

| 4. Surgeon | 4. Pharmacist |

| 5. NFL football player | 5. Medical assistant |

| 6. City police officer | 6. Typist/word processor |

| 7. Osteopath | 7. Librarian |

| 8. State police officer | 8. Janitor |

| 9. Air traffic controller | 9. Bookkeeper |

| 10. Mayor | 10. Forklift operator |

| Source: Adapted from The Jobs Rated Almanac by Les Krantz. 1988 Les Krantz. Reproduced from Rice University, Organizational Behavio, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | |

A second survey, by the American Psychological Association (2011), examined the specific causes of stress. The results of the study showed that the most frequently cited reasons for stress among administrative professionals are unspecified job requirements (38 percent), work interfering with personal time (36 percent), job insecurity (33 percent), and lack of participation in decision-making (33 percent). Finally, a study among managers found that they, too, are subject to considerable stress arising out of the nature of managerial work (Zauder & Fox, 1987). The more common work stressors for managers are shown in the table below.

Table 7.7 Typical Stressors Faced by Managers.

| Stressor | Example |

|---|---|

| Role ambiguity | Unclear job duties |

| Role conflict | Manager is both a boss and a subordinate. |

| Role overload | Too much work, too little time |

| Unrealistic expectations | Managers are often asked to do the impossible. |

| Difficult decisions | Managers have to make decisions that adversely affect subordinates. |

| Managerial failure | Manager fails to achieve expected results. |

| Subordinate failure | Subordinates let the boss down. |

| Source: Adapted from D. Zauderer and J. Fox, Resiliency in the Face of Stress, Management Solutions, November 1987, pp. 3233. Reproduced from Rice University, Organizational Behavio, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | |

Thus, a person’s occupation or profession represents a major cause of stress-related problems at work. In addition to occupation, however, and indeed closely related to it, is the problem of one’s role expectations in the organization. Three interrelated role processes will be examined as they relate to experienced stress: role ambiguity, role conflict, and role overload or underutilization.

Role Ambiguity

The first role process variable to be discussed here is role ambiguity. When individuals have inadequate information concerning their roles, they experience role ambiguity. Uncertainty over job definition takes many forms, including not knowing expectations for performance, not knowing how to meet those expectations, and not knowing the consequences of job behavior. Role ambiguity is particularly strong among managerial jobs, where role definitions and task specification lack clarity. For example, the manager of accounts payable may not be sure of the quantity and quality standards for their department. The uncertainty of the absolute level of these two performance standards or their relative importance to each other makes predicting outcomes such as performance evaluation, salary increases, or promotion opportunities equally difficult. All of this contributes to increased stress for the manager. Role ambiguity can also occur among nonmanagerial employees—for example, those whose supervisors fail to make sufficient time to clarify role expectations, thus leaving them unsure of how best to contribute to departmental and organizational goals.

Role ambiguity has been found to lead to several negative stress-related outcomes. French and Caplan (1972) summarized their study findings as follows:

“In summary, role ambiguity, which appears to be widespread, (1) produces psychological strain and dissatisfaction; (2) leads to underutilization of human resources; and (3) leads to feelings of futility on how to cope with the organizational environment” (p. 36)

In other words, role ambiguity has far-reaching consequences beyond experienced stress, including employee turnover and absenteeism, poor coordination and utilization of human resources, and increased operating costs because of inefficiency. It should be noted, however, that not everyone responds in the same way to role ambiguity. Studies have shown that some people have a higher tolerance for ambiguity and are less affected by role ambiguity (in terms of stress, reduced performance, or propensity to leave) than those with a low tolerance for ambiguity (French & Caplan, 1972). Thus, again we can see the role of individual differences in moderating the effects of environmental stimuli on individual behavior and performance.

Role Conflict

The second role-related factor in stress is role conflict. This may be defined as the simultaneous occurrence of two (or more) sets of pressures or expectations; compliance with one would make it difficult to comply with the other. In other words, role conflict occurs when an employee is placed in a situation where contradictory demands are placed upon them. For instance, a factory worker may find himself in a situation where the supervisor is demanding greater output, yet the work group is demanding a restriction of output. Similarly, a secretary who reports to several supervisors may face a conflict over whose work to do first.

One of the best-known studies of role conflict and stress was carried out by Robert Kahn and his colleagues at the University of Michigan. Kahn studied 53 managers and their subordinates (a total of 381 people), examining the nature of each person’s role and how it affected subsequent behavior. As a result of the investigation, the following conclusions emerged:

Contradictory role expectations give rise to opposing role pressures (role conflict), which generally have the following effects on the emotional experience of the focal person: intensified internal conflicts, increased tension associated with various aspects of the job, reduced satisfaction with the job and its various components, and decreased confidence in superiors and in the organization as a whole. The strain experienced by those in conflict situations leads to various coping responses, social and psychological withdrawal (reduction in communication and attributed influence) among them.

Finally, the presence of conflict in one’s role tends to undermine a person’s reactions with the individuals who dictate the role and to produce weaker bonds of trust, respect, and attraction. It is quite clear that role conflicts are costly for the person in emotional and interpersonal terms. They may be costly to the organization, which depends on effective coordination and collaboration within and among its parts (Kahn et al., 1964).

Other studies have found similar results concerning the serious side effects of role conflict both for individuals and organizations (Quick & Quick, 1984; Sutton & Rafaeli, 1987). It should again be recognized, however, that personality differences may serve to moderate the impact of role conflict on stress. In particular, it has been found that introverts and people who lack flexibility respond more negatively to role conflict than do others (French & Caplan). In any event, managers must be aware of the problem of role conflict and look for ways to avert negative consequences. One way this can be accomplished is by ensuring that their subordinates are not placed in contradictory positions within the organization; that is, subordinates should have a clear idea of what the manager’s job expectations are and should not be placed in “win-lose” situations.

Role Overload and Underutilization

Finally, in addition to role ambiguity and conflict, a third aspect of role processes has also been found to represent an important influence on experienced stress—namely, the extent to which employees feel either overloaded or underutilized in their job responsibilities. Role overload is a condition in which individuals feel they are being asked to do more than time or ability permits. Individuals often experience role overload as a conflict between quantity and quality of performance. Quantitative overload consists of having more work than can be done in a given time period, such as a clerk expected to process 1,000 applications per day when only 850 are possible. Overload can be visualized as a continuum ranging from too little to do to too much to do. Qualitative role overload, on the other hand, consists of being taxed beyond one’s skills, abilities, and knowledge. It can be seen as a continuum ranging from too-easy work to too-difficult work. For example, a manager who is expected to increase sales but has little idea of why sales are down or what to do to get sales up can experience qualitative role overload. It is important to note that either extreme represents a bad fit between the abilities of the employee and the demands of the work environment. A good fit occurs at that point on both scales of workload where the abilities of the individual are relatively consistent with the demands of the job.

There is evidence that both quantitative and qualitative role overload are prevalent in our society. What induces this overload? As a result of a series of studies, French and Caplan concluded that a major factor influencing overload is the high achievement needs of many managers. Need for achievement correlated very highly both with the number of hours worked per week and with a questionnaire measure of role overload. In other words, much role overload is apparently self-induced.

Similarly, the concept of role underutilization should also be acknowledged as a source of experienced stress. Role underutilization occurs when employees are allowed to use only a few of their skills and abilities, even though they are required to make heavy use of them. The most prevalent characteristic of role underutilization is monotony, where the worker performs the same routine task (or set of tasks) over and over. Other situations that make for underutilization include total dependence on machines for determining work pace and sustained positional or postural constraint. Several studies have found that underutilization often leads to low self-esteem, low life satisfaction, and increased frequency of nervous complaints and symptoms (Gardell, 1976).

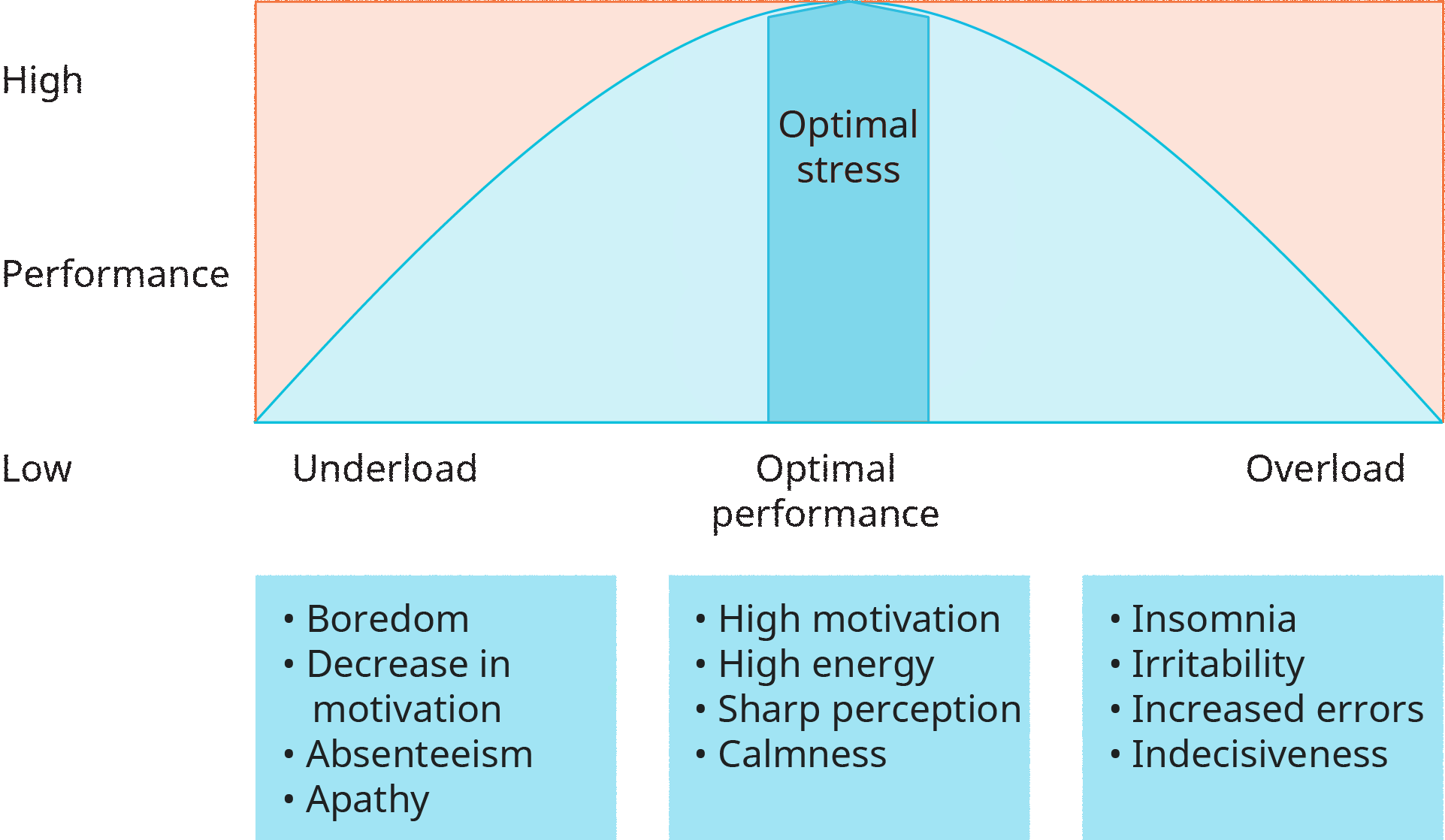

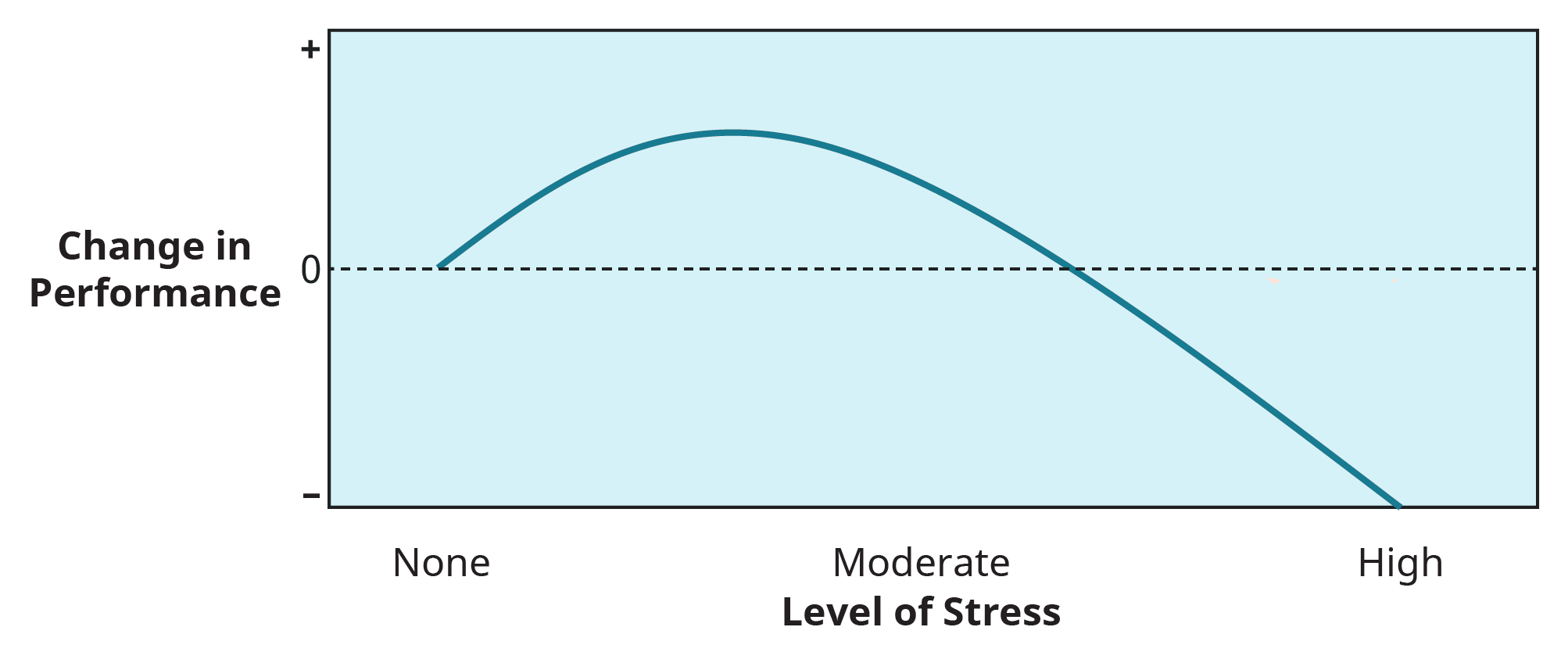

Both role overload and role underutilization have been shown to influence psychological and physiological reactions to the job. The inverted U-shaped relationship between the extent of role utilization and stress is shown in Figure 7.12. As shown, the least stress is experienced at that point where an employee’s abilities and skills are in balance with the requirements of the job. This is where performance should be highest. Employees should be highly motivated and should have high energy levels, sharp perception, and calmness. (Recall that many of the current efforts to redesign jobs and improve the quality of work are aimed at minimizing overload or underutilization in the workplace and achieving a more suitable balance between abilities possessed and skills used on the job.) When employees experience underutilization, boredom, decreased motivation, apathy, and absenteeism will be more likely. Role overload can lead to such symptoms as insomnia, irritability, increased errors, and indecisiveness.

Taken together, occupation and role processes represent a sizable influence on whether or not an employee experiences high stress levels.

Self -Assessment

See Appendix B: Self-Assessments

This instrument focuses on the stress level of your current (or previous) job.

Personal Influences on Stress

The second major influence on job-related stress can be found in the employees themselves. As such, we will examine three individual-difference factors as they influence stress at work: personal control, Type A personality, and rate of life change.

Personal Control

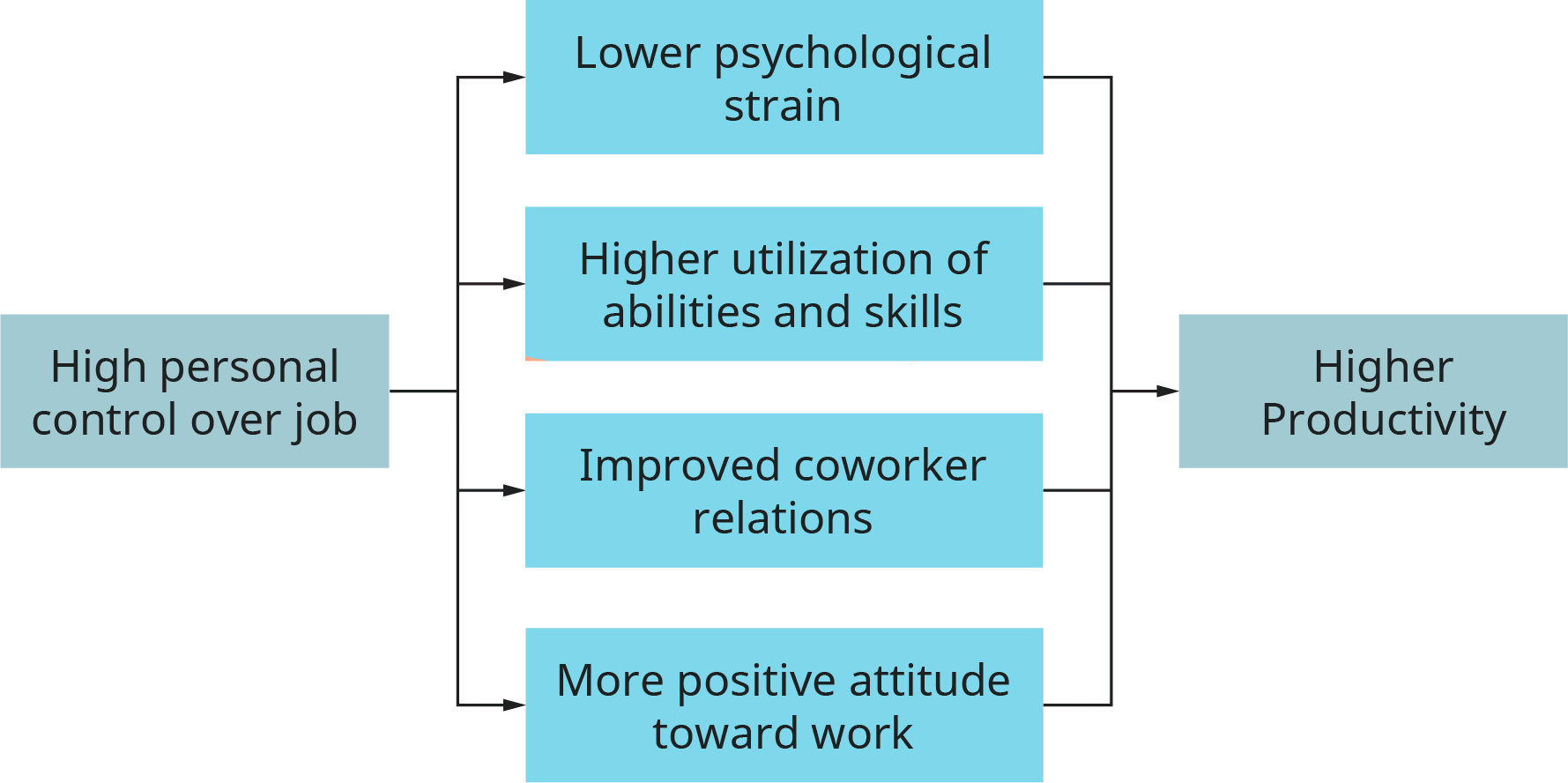

To begin with, we should acknowledge the importance of personal control as a factor in stress. Personal control represents the extent to which an employee actually has control over factors affecting effective job performance. If an employee is assigned a responsibility for something (landing an airplane, completing a report, meeting a deadline) but is not given an adequate opportunity to perform (because of too many planes, insufficient information, insufficient time), the employee loses personal control over the job and can experience increased stress. Personal control seems to work through the process of employee participation. That is, the more employees are allowed to participate in job-related matters, the more control they feel for project completion. On the other hand, if employees’ opinions, knowledge, and wishes are excluded from organizational operations, the resulting lack of participation can lead not only to increased stress and strain, but also to reduced productivity.

The importance of employee participation in enhancing personal control and reducing stress is reflected in the French and Caplan study discussed earlier. After a major effort to uncover the antecedents of job-related stress, these investigators concluded:

“Since participation is also significantly correlated with low role ambiguity, good relations with others, and low overload, it is conceivable that its effects are widespread, and that all the relationships between these other stresses and psychological strain can be accounted for in terms of how much the person participates. This, in fact, appears to be the case. When we control or hold constant, through statistical analysis techniques, the amount of participation a person reports, then the correlations between all the above stresses and job satisfaction and job-related threat drop quite noticeably. This suggests that low participation generates these related stresses, and that increasing participation is an efficient way of reducing many other stresses which also lead to psychological strain.” (French & Caplan, 1972, p. 51).

On the bases of this and related studies, we can conclude that increased participation and personal control over one’s job is often associated with several positive outcomes, including lower psychological strain, increased skill utilization, improved working relations, and more-positive attitudes. These factors, in turn, contribute toward higher productivity. These results are shown in Figure 7.10 (Schuler & Jackson, 1986).

Related to the issue of personal control—indeed, moderating its impact—is the concept of locus of control. It will be remembered that some people have an internal locus of control, feeling that much of what happens in their life is under their own control. Others have an external locus of control, feeling that many of life’s events are beyond their control. This concept has implications for how people respond to the amount of personal control in the work environment. That is, internals are more likely to be upset by threats to the personal control of surrounding events than are externals. Recent evidence indicates that internals react to situations over which they have little or no control with aggression—presumably in an attempt to reassert control over ongoing events (Carver & Glass, 1978; Fusilier et al., 1986). On the other hand, externals tend to be more resigned to external control, are much less involved in or upset by a constrained work environment, and do not react as emotionally to organizational stress factors. Hence, locus of control must be recognized as a potential moderator of the effects of personal control as it relates to experienced stress.

Type A Personality

Research has focused on what is perhaps the single most dangerous personal influence on experienced stress and subsequent physical harm. This characteristic was first introduced by Friedman and Rosenman (1974) and is called Type A personality. Type A and Type B personalities are felt to be relatively stable personal characteristics exhibited by individuals. Type A personality is characterized by impatience, restlessness, aggressiveness, competitiveness, polyphasic activities (having many “irons in the fire” at one time), and being under considerable time pressure. Work activities are particularly important to Type A individuals, and they tend to freely invest long hours on the job to meet pressing (and recurring) deadlines. Type B people, on the other hand, experience fewer pressing deadlines or conflicts, are relatively free of any sense of time urgency or hostility, and are generally less competitive on the job. These differences are summarized in Table 7.8.

Table 7.8 Profiles of Type A and Type B Personalities

| Type A | Type B |

|---|---|

| Highly competitive | Lacks intense competitiveness |

| Workaholic | Work only one of many interests |

| Intense sense of urgency | More deliberate time orientation |

| Polyphasic behavior | Does one activity at a time |

| Strong goal-directedness | More moderate goal-directedness |

| Source: Rice University, Organizational Behavior, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | |

Type A personality is frequently found in managers. Indeed, one study found that 60 percent of managers were clearly identified as Type A, whereas only 12 percent were clearly identified as Type B (Howard et al., 1976). It has been suggested that Type A personality is most useful in helping someone rise through the ranks of an organization.

The role of Type A personality in producing stress is exemplified by the relationship between this behavior and heart disease. Rosenman and Friedman (1974) studied 3,500 men over an 8 1/2-year period and found Type A individuals to be twice as prone to heart disease, five times as prone to a second heart attack, and twice as prone to fatal heart attacks when compared to Type B individuals. Similarly, Jenkins (1971) studied over 3,000 men and found that of 133 coronary heart disease sufferers, 94 were clearly identified as Type A in early test scores. The rapid rise of women in managerial positions suggests that they, too, may be subject to this same problem. Hence, Type A behavior very clearly leads to one of the most severe outcomes of experienced stress. One irony of Type A is that although this behavior is helpful in securing rapid promotion to the top of an organization, it may be detrimental once the individual has arrived. That is, although Type A employees make successful managers (and salespeople), the most successful top executives tend to be Type B. They exhibit patience and a broad concern for the ramifications of decisions.

The key is to know how to shift from Type A behavior to Type B. How does a manager accomplish this? The obvious answer is to slow down and relax. However, many Type A managers refuse to acknowledge either the problem or the need for change, because they feel it may be viewed as a sign of weakness. In these cases, several small steps can be taken, including scheduling specified times every day to exercise, delegating more significant work to subordinates, and eliminating optional activities from the daily calendar. Some companies have begun experimenting with retreats, where managers are removed from the work environment and engage in group psychotherapy over the problems associated with Type A personality.

Rate of Life Change

A third personal influence on experienced stress is the degree to which lives are stable or turbulent. Recall our previous discussion of the work of Holmes and Rahe (1967). As a result of their research, a variety of life events were identified and assigned points based upon the extent to which each event is related to stress and illness. The death of a spouse was seen as the most stressful change and was assigned 100 points. Other events were scaled proportionately in terms of their impact on stress and illness. It was found that the higher the point total of recent events, the more likely it is that the individual will become ill.

Buffering Effects of Workplace Stress

We have seen in the previous discussion how a variety of organizational and personal factors influence the extent to which individuals experience stress on the job. Although many factors, or stressors, have been identified, their effect on psychological and behavioral outcomes is not always as strong as we might expect. This lack of a direct stressor-outcome relationship suggests the existence of potential moderator variables that buffer the effects of potential stressors on individuals. Recent research has identified two such buffers: the degree of social support the individual receives and the individual’s general degree of what is called hardiness. Both are noted in Figure 7.11.

Social Support

First, let us consider social support. Social support is simply the extent to which organization members feel their peers can be trusted, are interested in one another’s welfare, respect one another, and have a genuine positive regard for one another. When social support is present, individuals feel that they are not alone as they face the more prevalent stressors. The feeling that those around you really care about what happens to you and are willing to help blunts the severity of potential stressors and leads to less-painful side effects. For example, family support can serve as a buffer for executives on assignment in a foreign country and can reduce the stress associated with cross-cultural adjustment.

Much of the more rigorous research on the buffering effects of social support on stress comes from the field of medicine, but it has relevance for organizational behavior. In a series of medical studies, it was consistently found that high peer support reduced negative outcomes of potentially stressful events (surgery, job loss, hospitalization) and increased positive outcomes (Cohen & Wills, 1985). These results clearly point to the importance of social support to individual well-being. These results also indicate that managers should be aware of the importance of building cohesive, supportive work groups—particularly among individuals who are most subject to stress.

Hardiness

The second moderator of stress is hardiness. Hardiness represents a collection of personality characteristics that involve one’s ability to perceptually or behaviorally transform negative stressors into positive challenges. These characteristics include a sense of commitment to the importance of what one is doing, an internal locus of control, and a sense of life challenge. In other words, people characterized by hardiness have a clear sense of where they are going and are not easily deterred by hurdles. The pressure of goal frustration does not deter them, because they invest themselves in the situation and push ahead. Simply put, these are people who refuse to give up (Kobasa et al., 1982; Hull et al, 1987).

Several studies of hardiness support the importance of this variable as a stress moderator. One study among managers found that those characterized by hardiness were far less susceptible to illness following prolonged stress. And a study among undergraduates found hardiness to be positively related to perceptions that potential stressors were actually challenges to be met. Thus, factors such as individual hardiness and the degree of social support must be considered in any model of the stress process.

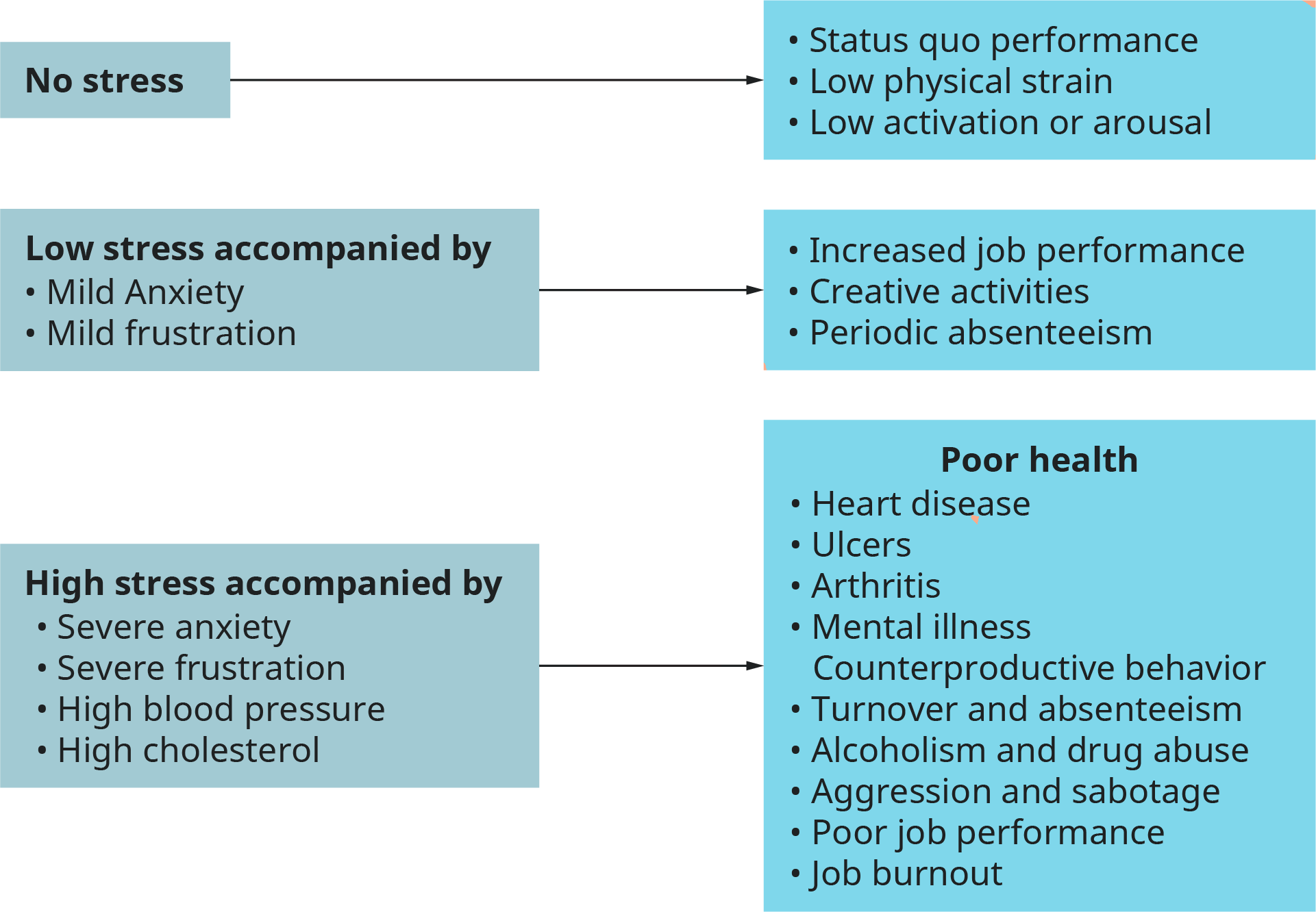

Degrees of Experienced Stress

In exploring major influences on stress, it was pointed out that the intensity with which a person experiences stress is a function of organizational factors and personal factors, moderated by the degree of social support in the work environment and by hardiness. We come now to an examination of major consequences of work-related stress. Here we will attempt to answer the “so what?” question. Why should managers be interested in stress and resulting strain?

As a guide for examining the topic, we recognize three intensity levels of stress—no stress, low stress, and high stress—and will study the outcomes of each level. These outcomes are shown schematically in Figure 7.14. Four major categories of outcome will be considered: (1) stress and health, (2) stress and counterproductive behavior, (3) stress and job performance, and (4) stress and burnout.

Stress and Health

High degrees of stress are typically accompanied by severe anxiety and/or frustration, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol levels. These psychological and physiological changes contribute to the impairment of health in several different ways. Most important, high stress contributes to heart disease (Cooper & Payne, 1986). The relationship between high job stress and heart disease is well established.

High job stress also contributes to a variety of other ailments, including peptic ulcers, arthritis, and several forms of mental illness. In a study by Cobb and Kasl, for example, it was found that individuals with high educational achievement but low job status exhibited abnormally high levels of anger, irritation, anxiety, tiredness, depression, and low self-esteem (Cobb & Kals, 1970).

In another study, Slote examined the effects of a plant closing in Detroit on stress and stress outcomes. Although factory closings are fairly common, the effects of these closings on individuals have seldom been examined. Slote found that the plant closing led to “an alarming rise in anxiety and illness,” with at least half the employees suffering from ulcers, arthritis, serious hypertension, alcoholism, clinical depression, and even hair loss (Slote, 1977). Clearly, this life change event took its toll on the mental and physical well-being of the workforce.

Finally, in a classic study of mental health of industrial workers, Kornhauser (1965) studied a sample of automobile assembly-line workers. Of the employees studied, he found that 40 percent had symptoms of mental health problems. His main findings may be summarized as follows:

- Job satisfaction varied consistently with employee skill levels. Blue-collar workers holding high-level jobs exhibited better mental health than those holding low-level jobs.

- Job dissatisfaction, stress, and absenteeism were all related directly to the characteristics of the job. Dull, repetitious, unchallenging jobs were associated with the poorest mental health.

- Feelings of helplessness, withdrawal, alienation, and pessimism were widespread throughout the plant. As an example, Kornhauser noted that 50 percent of the assembly-line workers felt they had little influence over the future course of their lives; this compares to only 17 percent for nonfactory workers.

- Employees with the lowest mental health also tended to be more passive in their nonwork activities; typically, they did not vote or take part in community activities.

In conclusion, Kornhauser noted:

“Poor mental health occurs whenever conditions of work and life lead to continuing frustration by failing to offer means for perceived progress toward attainment of strongly desired goals which have become indispensable elements of the individual’s self-esteem and dissatisfaction with life, often accompanied by anxieties, social alienation and withdrawal, a narrowing of goals and curtailing of aspirations—in short . . . poor mental health” (p. 342).

Managers need to be concerned about the problems of physical and mental health because of their severe consequences both for the individual and for the organization. Health is often related to performance, and to the extent that health suffers, so too do a variety of performance-related factors. Given the importance of performance for organizational effectiveness, we will now examine how it is affected by stress.

Stress and Counterproductive Behavior

It is useful from a managerial standpoint to consider several forms of counterproductive behavior that are known to result from prolonged stress. These counterproductive behaviors include turnover and absenteeism, alcoholism and drug abuse, and aggression and sabotage.

Turnover and Absenteeism

Turnover and absenteeism represent convenient forms of withdrawal from a highly stressful job. Results of several studies have indicated a fairly consistent, if modest, relationship between stress and subsequent turnover and absenteeism (Allen & Bryant, 2013; Mobley, 1982; Rhodes & Steers, 1990). In many ways, withdrawal represents one of the easiest ways employees have of handling a stressful work environment, at least in the short run. Indeed, turnover and absenteeism may represent two of the less undesirable consequences of stress, particularly when compared to alternative choices such as alcoholism, drug abuse, or aggression. Although high turnover and absenteeism may inhibit productivity, at least they do little physical harm to the individual or coworkers. Even so, there are many occasions when employees are not able to leave because of family or financial obligations, a lack of alternative employment, and so forth. In these situations, it is not unusual to see more dysfunctional behavior.

Abuse of Drugs and Alcohol

It has long been known that stress is linked to substance use and abuse by employees at all levels in the organizational hierarchy. These two forms of withdrawal offer a temporary respite from severe anxiety and severe frustration. Both alcohol and drugs are used by a significant proportion of employees to escape from the rigors of a routine or stressful job. Although many companies have begun in-house programs aimed at rehabilitating chronic cases, these forms of withdrawal seem to continue to be on the increase, presenting another serious problem for modern managers. One answer to this dilemma involves reducing stress on the job that is creating the need for withdrawal from organizational activities.

Aggression and Sabotage

Severe frustration can also lead to overt hostility in the form of aggression toward other people and toward inanimate objects. Aggression occurs when individuals feel frustrated and can find no acceptable, legitimate remedies for the frustration. A frustrated employee may react by covert verbal abuse or an intentional slowdown on subsequent work. A more extreme example of aggression can be seen in the periodic reports in newspapers about a worker who violently attacks fellow employees.

One common form of aggressive behavior on the job is sabotage – intentionally causing problems such as failures, damage or conflict. The extent to which frustration leads to aggressive behavior is influenced by several factors, often under the control of managers. Aggression tends to be subdued when employees anticipate that it will be punished, the peer group disapproves, or it has not been reinforced in the past (that is, when aggressive behavior failed to lead to positive outcomes). Thus, it is incumbent upon managers to avoid reinforcing undesired behavior and, at the same time, to provide constructive outlets for frustration. In this regard, some companies have provided official channels for the discharge of aggressive tendencies. For example, many companies have experimented with ombudsmen, whose task it is to be impartial mediators of employee disputes. Results have proved positive. These procedures or outlets are particularly important for nonunion personnel, who do not have contractual grievance procedures.

Stress and Job Performance

A major concern of management is the effects of stress on job performance. The relationship is not as simple as might be supposed. The stress-performance relationship resembles an inverted J-curve, as shown in Figure 7.12. At very low or no-stress levels, individuals maintain their current levels of performance. Under these conditions, individuals are not activated, do not experience any stress-related physical strain, and probably see no reason to change their performance levels. Note that this performance level may be high or low. In any event, an absence of stress probably would not cause any change.

On the other hand, studies indicate that under conditions of low stress, people are activated sufficiently to motivate them to increase performance. For instance, salespeople and many managers perform best when they are experiencing mild anxiety or frustration. Stress in modest amounts, as when a manager has a tough problem to solve, acts as a stimulus for the individual. The toughness of a problem often pushes managers to their performance limits. Similarly, mild stress can also be responsible for creative activities in individuals as they try to solve difficult (stressful) problems.

Finally, under conditions of high stress, individual performance drops markedly. Here, the severity of the stress consumes attention and energies, and individuals focus considerable effort on attempting to reduce the stress (often employing a variety of counterproductive behaviors as noted below). Little energy is left to devote to job performance, with obvious results.

Stress and Burnout

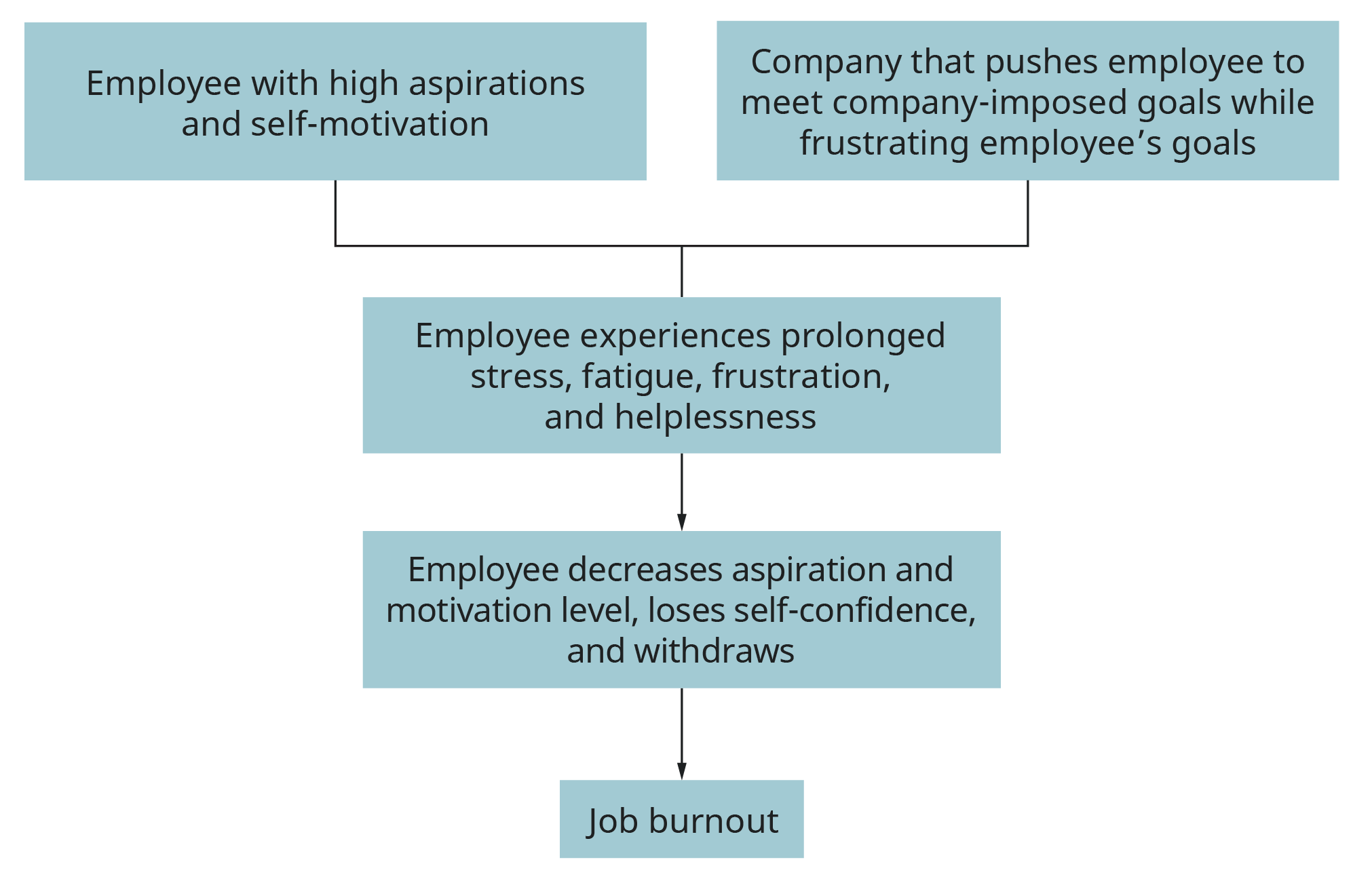

When job-related stress is prolonged, poor job performance such as that described above often moves into a more critical phase, known as burnout. Burnout is a general feeling of exhaustion that can develop when a person simultaneously experiences too much pressure to perform and too few sources of satisfaction (Jackson et al., 1986).

Candidates for job burnout seem to exhibit similar characteristics. That is, many such individuals are idealistic and self-motivated achievers, often seek unattainable goals, and have few buffers against stress. As a result, these people demand a great deal from themselves, and, because their goals are so high, they often fail to reach them. Because they do not have adequate buffers, stressors affect them rather directly. This is shown in Figure 7.15. As a result of experienced stress, burnout victims develop a variety of negative and often hostile attitudes toward the organization and themselves, including fatalism, boredom, discontent, cynicism, and feelings of personal inadequacy. As a result, the person decreases their aspiration levels, loses confidence, and attempts to withdraw from the situation.

Research indicates that burnout is widespread among employees, including managers, researchers, and engineers, that are often hardest to replace by organizations. As a result, many companies offer stress reduction programs.

Stress, Burnout, Trauma, and Structural Violence

Much of the discussion of stress so far refers to personal and interpersonal factors, which does not account for the inextricable links between stress and institutions, systems, and structures that enable and/or enact harm. Structural violence was a term coined by Galtung (1969) to refer to “social injustice” (p. 171), particularly in the context of the negative and disproportionate impacts of some systems and institutions on marginalized communities.

Nagoski and Nagoski (2019) discuss stress and burnout within the context of inequitable systems, such as patriarchy and white supremacy; they offer the following analogy:

“White men grow on an open, level field. White women grow on far steeper and rougher terrain because the field wasn’t made for them. Women of color grow not just on a hill, but on a cliff-side over the ocean, battered by wind and waves. None of us chooses the landscape in which we’re planted” (p. 94)

Further, Thompson (2021) proposes institutional trauma as a framework through which we can account for the situated and complex aspects of trauma that can be bound up with patriarchy, colonialism, white supremacy, and other systems of oppression. Overall, causes and responses to stress, burnout, and trauma can be complex and varied. As structural violence can be enacted and reproduced in organizational spaces, it is important to consider this in addressing stress, burnout, and trauma in workplaces.

What role can/should organizations play in helping to prevent/reduce employee stress and burnout?

Krista’s Book Club

Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle is co-authored by sisters Amelia and Emily Nagoski. They examine various stressors that lead to burnout in women and factors (including structural and systemic barriers) that impact women’s mental and physical health. This book helps readers understand the body’s physiological responses to stress and how our thoughts and emotions relate to stress. Nagoski and Nagoski suggest awareness of our inner thoughts and feelings, rest, and connection can all serve as antidotes to burnout.

Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle is co-authored by sisters Amelia and Emily Nagoski. They examine various stressors that lead to burnout in women and factors (including structural and systemic barriers) that impact women’s mental and physical health. This book helps readers understand the body’s physiological responses to stress and how our thoughts and emotions relate to stress. Nagoski and Nagoski suggest awareness of our inner thoughts and feelings, rest, and connection can all serve as antidotes to burnout.

Students may also be interested in this audiocast from TED Health: The cure for burnout (hint: It isn’t self-care).

References

Nagoski, E., & Nagoski, A. (2019) Burnout: The secret to unlocking the stress cycle. Ballatine Books.

Self-assessment

See Appendix B: Self-Assessments

Check whether each item is “mostly true” or “mostly untrue” for you.

Stress: An Occupational Health and Safety Perspective

Psycho-social hazards are the social and psychological factors that negatively affect worker health and safety. Psycho-social hazards can be hard to isolate in the workplace because they reside in the dynamics of human interactions and within the internal world of an individual’s psyche. Yet it is increasingly recognized that social and psychological aspects of work have real and measurable effects on workers’ health. Harassment, bullying, and violence are examples of psycho-social hazards. Other forms include stress, fatigue, and overwork. Even the absence of social interaction, in the form of working alone, produces its own hazards. Much of the challenge is recognizing that these hazards pose real threats to workers’ health. This section examines stress from an occupational health and safety perspective.

We all experience stress at some point in our lives. As we learned in the previous section, stress can have a positive effect, making us more alert or more prepared to take on an important challenge. Stress can also have a negative effect, causing a range of physical and mental ailments. Stress can arise from all aspects of our lives, including our work. Workplace stress is stress that is brought on by work-related stressors. Canadians report work to be the biggest source of life stress. Almost three quarters of Canadian workers report that their work entails some stress, with 27% reporting that work is “quite a bit” or “extremely” stressful (Crompton, 2011). The most frequently identified workplace stressors are heavy workloads, low salaries, lack of opportunity, unrealistic or uncertain job expectations, and lack of control over work (APA, 2015). Researchers typically identify five factors contributing to workplace stress:

- characteristics of the job being performed, such as workload, pace, autonomy, and physical working conditions,

- a worker’s level of responsibility in the workplace, including the clarity of their role,

- job (in)security, promotion, and career development opportunities,\

- problematic interpersonal work relationships with supervisors, co-workers, or subordinates, including harassment and discrimination, and

- overall organizational structure and climate, including organizational communication patterns, management style, and participation in decision making (job control).

These five factors demonstrate that workplace stress arises out of situations and events within the employer’s control. This, in turn, makes the occurrence of workplace stress an occupational health and safety issue.

Workplace stress produces a range of physical and mental health effects. Early physical signs of negative stress include increased heart rate, sweating, and nausea, reddening of the skin, muscle tension, and headaches. Early emotional and mental effects of negative stress include anxiety, depression, apathy, sleep disturbance, and irritability. Long-lasting or intensifying stress results in a worsening of these symptoms as well as the appearance of new symptoms, such as lasting depression, heart disease, chronic digestive issues, reduced sex drive, uneven metabolism, and increased susceptibility to infectious diseases.

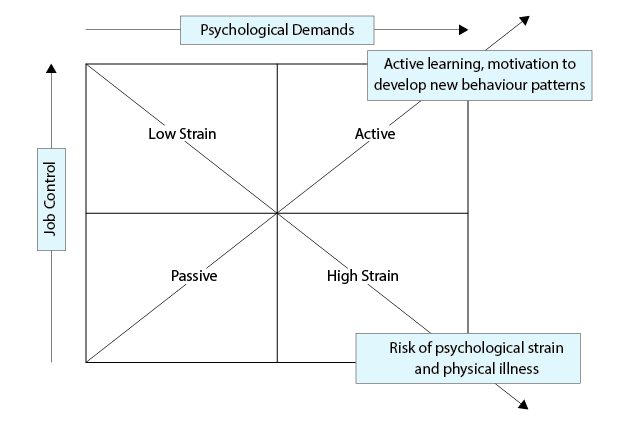

Research led by Robert Karasek has revealed that job control is a key factor in determining how work-related stress affects us. His job demands-control model is explained in Figure 7.16. It is also possible for negative effects of stress to manifest themselves in groups of workers and not just individuals, due to workplace dynamics and environment. Group manifestation can arise from so-called toxic workplaces. Toxic workplaces are characterized by “relentless demands, extreme pressure, and brutal ruthlessness,” and represent the extreme of stressful workplace environments (Macklem, 2005).

Karasek’s job demands-control model

Before Robert Karasek’s groundbreaking work, most research into work-related stress focused on the effects of job demands, such as overload. Karasek discovered that the degree of control a worker has in her job plays a significant role in whether job-related stress will be positive or negative and whether ill health results (Karasek, 1979).

Karasek developed a model that analyzed the interaction of job demands with job control. He created a matrix that included four types of work, as illustrated below (adapted from Karasek, 1979).

Low-strain and passive jobs are associated with low stress, although passive jobs can lead to low motivation and dissatisfaction. The important boxes are active jobs, associated with high job demands but where workers possess a high degree of decision latitude (i.e., control) in the work, and high-strain jobs, which contain high demand but little job control. The cumulative effect of working in an active job is that workers builds their ability to cope with stress. Conversely, sustained exposure to high-strain work leads to psychological and physical illness.

Karasek and his research partner later added the concept of “social support” to the model. Social support is the degree of isolation or support provided by both supervisors and co-workers. They found that high levels of social support can mitigate some of the negative effects of high-strain work. They also note that the most hazardous form of work is work combining high demand, low control, and low social support (Karasek & Theorell, 1992). Karasek found the effects most acute for workers in blue-collar occupations, which typically give workers little job control.

Research into the model has found links between high-strain jobs and high incidence of heart disease, hypertension, mental health issues, and other negative health outcomes. While men and women experience job strain in similar ways, some recent research suggests that the presence of social support has a stronger effect in ameliorating negative stress effects for women than for men (Rivera-Torres et al., 2013). Also, the stress-buffering effects of job control have a greater impact on older workers than younger workers, suggesting older workers have developed coping techniques that younger workers have yet to discover (Shutlz et al., 2010).

Karasek’s groundbreaking work reveals that job design, work environment, and worker autonomy are significant factors in determining whether work stressors will lead to negative health effects for workers. This finding suggests that HR tasks such as job design can profoundly affect the workplace hazards faced by workers.

There are two main challenges associated with recognizing workplace stress as a hazard. First, stress is often perceived as an individual’s response to a situation, and any two individuals can react differently to the same stressor. This perception can lead managers to identify the issue with the individual rather than the stressor itself. This response is an example of an employer blaming the worker for an injury. Faced with an explanation that blames the worker, it is important to be cognizant of the difference between root and proximate cause. “Stress is not merely a physiological response to a stressful situation. Stress is an interaction between that individual and source of demand within their environment” (Colligan & Higgins, 2006, p. 92). In other words, while individuals may respond differently to stressors (which is the proximate cause of the health effect), the root cause of the reaction is the workplace dynamics that create the stressor.

Second, isolating workplace stressors can be difficult, especially chronic stressors. Non-work stressors do affect workers and can also be used by employers as an excuse to deny that stress-related health effects have workplace causes. Also, as with other types of ill health, individuals have different tolerances for stress, meaning the same stressors may affect one worker more than another. As a result, it can be difficult to have chronic stress recognized as a workplace hazard or the cause of a workplace injury or ill health. A workers’ compensation board, for example, is more likely to accept claims resulting in catastrophic or acute stress (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder) than chronic stress.

Consider This: Workers’ Compensation and Chronic Stress

In January 2007, Parks Canada employee Douglas Martin filed a claim with Alberta’s WCB for chronic stress. For the previous seven years, Martin had spearheaded an effort to have park wardens armed while they were performing their duties (an ongoing health and safety issue in Parks Canada). This effort was stressful and conflict-ridden, and Martin felt he had experienced reprisals by his employer in the form of lack of promotion, training, and work.

The previous month, Martin had received a letter threatening him with disciplinary action over an unrelated matter. Martin “already had a written reprimand on his file and feared that the next disciplinary action would be dismissal. He alleged the letter, following the stress of years of conflict over the health and safety issue, triggered a psychological condition. He took medical leave beginning December 23, 2006, consulted medical professionals for treatment, and initiated a claim for compensation for chronic onset stress the following month.”

Martin’s workers’ compensation claim was refused and he lost his appeals of the decision. Alberta’s WCB policy stated that it accepts claims for chronic stress only if the worker meets each of four criteria:

- there is a confirmed psychological or psychiatric diagnosis as described in the psychiatric manual of mental disorders (commonly called DSM),

- the work-related events or stressors are the predominant cause of the injury; predominant cause means the prevailing, strongest, chief, or main cause of the chronic onset stress,

- the work-related events are excessive or unusual in comparison to the normal pressures and tensions experienced by the average worker in a similar occupation, and

- there is objective confirmation of the events.

The WCB accepted that Martin was experiencing psychological effects and that the stressors were predominantly work-related. They denied the claim on the grounds that the events were not excessive or unusual in comparison to normal pressures and that there was not objective confirmation of the events.

As in all WCB cases, the decision revolves around the specifics of Martin’s situation. Nevertheless, it demonstrates how the bar to successfully establish a WCB claim for chronic stress can be set so high as to be unreachable by most workers. Further, the requirement that the events be “excessive or unusual in comparison to the normal pressures and tensions experienced by the average worker” marginalizes workers who may have a heightened sensitivity to stress. Finally, the decision, by arguing that fear of dismissal is not unusual in the workplace, downplays the role of management in creating an unusually stressful situation.

Workplace stress is the result of workplace factors. Consequently, preventing the negative effects of workplace stress requires changes to job design, workload, organizational culture, and interpersonal dynamics. These factors are both broadly known to employers and within their control. What the persistence of stressful workplaces reveals is that employers in such workplaces prioritize maintaining profitability, productivity, and control of the work process over workers’ health.

Related to stress is the experience of fatigue. Fatigue is the state of feeling tired, weary, or sleepy caused by insufficient sleep, prolonged mental or physical work, or extended periods of stress or anxiety. Acute, or short-term, fatigue can be caused by failure to get adequate sleep in the period before a work shift and is resolved quickly through appropriate sleep. Chronic fatigue can be the result of a prolonged period of sleep deficit and may require more involved treatment. Chronic fatigue syndrome is an ongoing, severe feeling of tiredness not relieved by sleep. The causes of chronic fatigue syndrome are unknown.

While lack of sleep is the primary cause of fatigue, it can be enhanced by other factors, including drug or alcohol use, high temperatures, boring or monotonous work, loud noise, dim lighting, extended shifts, or rotating shifts. As with other conditions, workers have differing sensitivity to fatigue. Fatigue can also make workers more susceptible to stress and illness. Fatigue is a legitimate health and safety concern because workers who are experiencing fatigue are more likely to be involved in workplace incidents. Lack of alertness and reduced decision-making capacity can have negative effects on safety. Research has shown that fatigue can impair judgment in a manner similar to alcohol.

Most cases of fatigue are resolved through adequate sleep. The average person requires 7.5 to 8.5 hours of sleep a night (remember, this is an average—some require more, some less). While an employer cannot control how well a worker sleeps, they can adjust the workplace to mitigate fatigue. Shift scheduling is one of the most important administrative controls of fatigue: employers can ensure shifts are not too long or too close together as well as avoiding dramatic shift rotations. Employers can also ensure that workplace temperatures are not too high, work is interesting and engaging without being too strenuous, and adequate opportunities for resting, eating, and sleeping (if necessary) are provided.

Adapted Works

“Psycho-social Hazards” in Health and Safety in Canadian Workplaces by Jason Foster and Bob Barnetson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

“Stress and Wellbeing” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

Allen, D., & Bryant, P. (2013). Managing employee turnover: Dispelling myths and fostering evidence-based retention strategies. Business Expert Press.

American Psychological Association. (2011). Stress in the workplace. APA.

American Psychological Association. (2015). 2015 work and well-being survey. APA.

Carver, C., & Glass, D. (1978). Coronary prone behavior pattern and interpersonal aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 361–366.

Cobb, S., & Kasl, S. (1970). Blood pressure changes in men undergoing job loss: A preliminary report. Psychosomatic Medicine, 32(1), 19–38.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357.

Colligan, T., & Higgins, E. (2006). Workplace stress. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 21(2), 89–97.

Cooper, C. & Payne, R. (1986). Stress at work. Wiley.

Crompton, S. (2011, October). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Canadian Social Trends, 98(2), 44–51.

French, J. & Caplan, R. (1972). Organizational stress and individual strain. In A. Marrow (Ed.), The failure of success. Amacom.

Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. (1974). Type A behavior and your heart. Knopf.

Fusilier, M., Ganster, D., & Mayes, B. (1986). The social support and health relationship: Is there a gender difference? Journal of Occupational Psychology, 59(2), 145–153.

Gardell, G. (1976). Arbetsinnehall och livskvalitet. Prisma.

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167–191. http://www.jstor.org/stable/422690

Hamner, W. C., & Organ, D. (1978). Organizational behavior. BPI.

Holmes, T., H. & Rahe, R. H. (1976). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 213–218.

Howard, J., Cunningham, D., & Rechnitzer, P. (1976). Health patterns associated with Type A behavior: A managerial population. Journal of Human Stress, 2(1), 24–31.

Hull, J., VanTreuren, R., & Virnelli, S. (1987). Hardiness and health: A critique and alternative approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 518–530.

Jackson, S. Schwab, R., & Schuler, R. (1986). Toward an understanding of the burnout phenomenon. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(4), 630–640.

Jenkins, C. (1971). Psychologic disease and social prevention of coronary disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 244–255.

Kahn, R., Wolfe, D., Quinn, R., Snoek, J., & Rosenthal, R. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. Wiley.

Karasek, R. (1979). Job Demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–308.

Karasek, R., & Theorell, T. (1992). Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books.

Kobasa, S., Maddi, S., & Kahn, S. (1982). Hardiness and health: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 168–177.

Kornhauser, A. (1965). Mental health and the industrial worker. Wiley.

Macklem, K. (2005). The toxic workplace. Maclean’s, 118(5), 34.

McGrath, J. (1976). Stress and behavior in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Rand McNally.

Mobley, W. (1990). Managing employee turnover. Addison-Wesley.

Nagoski, E. & Nagoski, A. (2019). Burnout: The secret to unlocking the stress cycle. Ballantine Books.

Quick, J., & Quick, J. (1984). Organizational stress and preventive management. McGraw-Hill.

Rivera-Torres, P., Araque-Padilla, R., & Montero-Simó, M. (2013). Job stress across gender: The importance of emotional and intellectual demands and social support in women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(1), 375–389.

Rhodes, S., & Steers, R. (1990). Managing employee absenteeism. Addison-Wesley.

Schuler, R. & Jackson, S. (1986). Managing stress through P/HRM practices. In K. Rowland and G. Ferris, (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resource management (pp. 183-224). JAI Press.

Slote, A. (1977). Termination: The closing of baker plant. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Sutton, R., & Rafaeli, A. (1987). Characteristics of work stations as potential occupational stressors. Academy of Management Journal, 30(2), 260–276.

Terkel, S. (1972). Working. Avon.

Thompson, L. (2021). Toward a feminist psychological theory of “institutional trauma”. Feminism & Psychology, 31(1), 99-118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353520968374