2.2 Approaches to Conflict

Approaches to Conflict

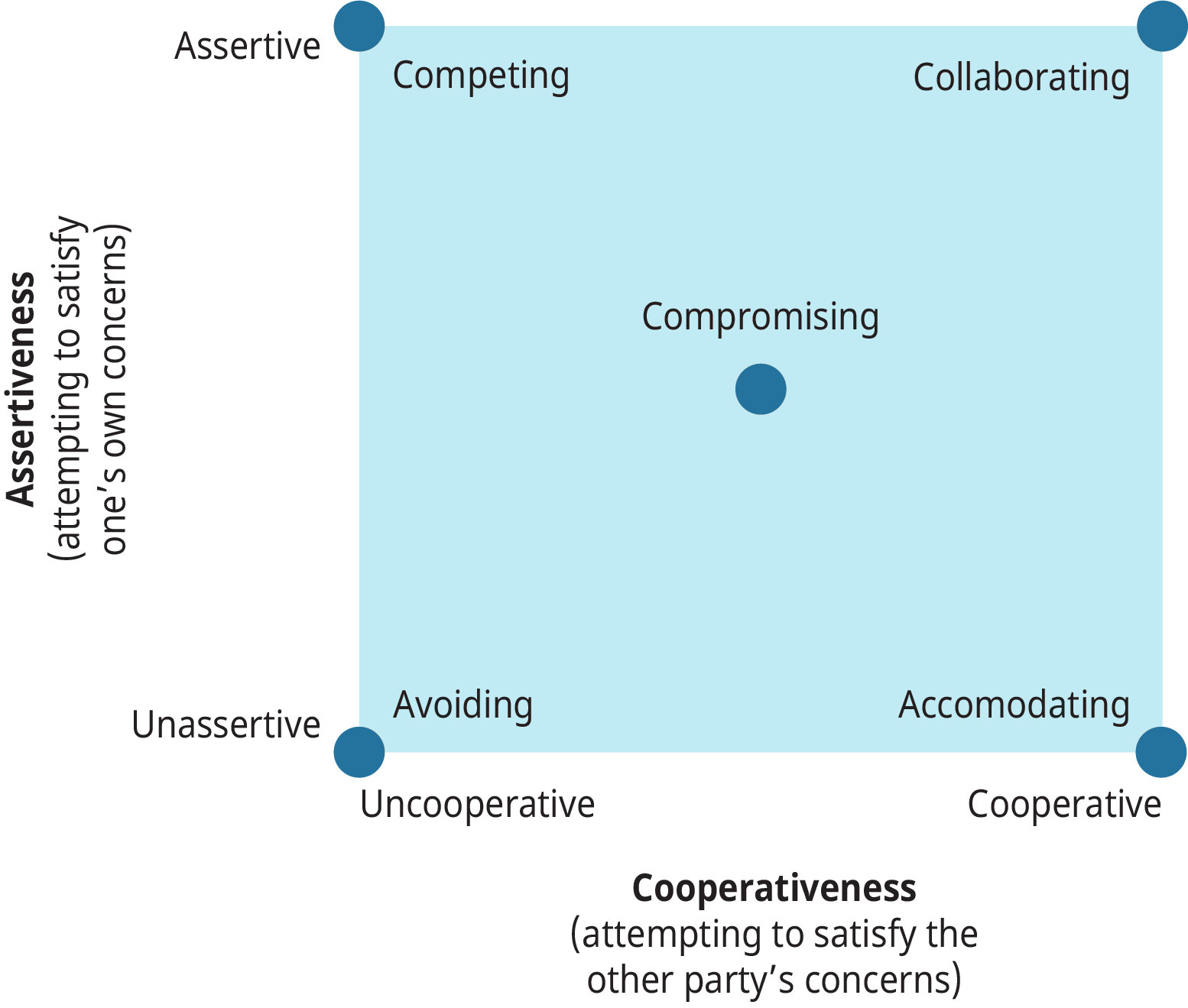

Every individual or group manages conflict differently. In the 1970s, consultants Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann developed a tool for analyzing the approaches to conflict resolution. This tool is called the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) (Kilmann Diagnostics, n.d.).

Thomas and Kilmann suggest that in a conflict situation, a person’s behaviour can be assessed on two factors:

- Commitment to goals or assertiveness—the extent to which an individual (or a group) attempts to satisfy his or her own concerns or goals. A person may behaviour in behaviour that is not assertive or is highly assertive.

- Commitment to relationships or cooperation—the extent to which an individual (or a group) attempts to satisfy the concerns of the other party, and the importance of the relationship with the other party. A person may behave in a may that is uncooperative or highly cooperative.

Thomas and Kilmann use these factors to explain the five different approaches to dealing with conflict: avoiding, competing, accommodating, compromising, and collaborating. These approaches are pictured in Figure 2.3 below.

Let’s take a closer look at each approach and when to use it.

Avoidance

An avoidance approach to conflict demonstrates a low commitment to both goals and relationships. This is the most common method of dealing with conflict, especially by people who view conflict negatively.

Table 2.2 Avoiding

| Types of Avoidance | Results | Appropriate When |

|---|---|---|

| Physical flight | The dispute is not resolved. | The issue is trivial or unimportant, or another issue is more pressing |

| Mental withdrawal | Disputes often build up and eventually explode. | Potential damage outweighs potential benefits |

| Changing the subject | Low satisfaction results in complaining, discontentment, and talking back. | Timing for dealing with the conflict is inappropriate (because of overwhelming emotions or lack of information) |

| Blaming or minimizing | Stress spreads to other parties (e.g., co-workers, family). | |

| Denial that the problem exists | ||

| Postponement to a more appropriate time (which may never occur) | ||

| Use of emotions (tears, anger, etc.) | ||

| Source: Leadership and Influencing Change In Nursing by Joan Wagner, CC BY 4.0. | ||

People exhibiting the avoidance style seek to avoid conflict altogether by denying that it is there. They are prone to postponing any decisions in which a conflict may arise. People using this style may say things such as, “I don’t really care if we work this out,” or “I don’t think there’s any problem. I feel fine about how things are.” Conflict avoidance may be habitual to some people because of personality traits such as the need for affiliation. While conflict avoidance may not be a significant problem if the issue at hand is trivial, it becomes a problem when individuals avoid confronting important issues because of a dislike for conflict or a perceived inability to handle the other party’s reactions.

It is important to consider that there are some situations that avoidance may be the most appropriate course of action. When a situation is minor, it may not be worth the time and effort to pursue. When a conflict or the potential outcome is serious, avoiding a person/situation may also be the appropriate course of action. Avoidance is also different than taking a break to gather your thoughts and calm emotion or find a more appropriate setting to have a conversation. If you take a break, make sure it’s not a strategy to avoid. If possible, try to plan for when to resume the discussion.

Competing

A competing approach to conflict demonstrates a high commitment to goals and a low commitment to relationships. Individuals who use the competing approach pursue their own goals at the other party’s expense. People taking this approach will use whatever power is necessary to win. It may display as defending a position, interest, or value that you believe to be correct. Competing approaches are often supported by structures (courts, legislatures, sales quotas, etc.) and can be initiated by the actions of one party. Competition may be appropriate or inappropriate (as defined by the expectations of the relationship).

Table 2.3 Competing

| Types of Competing | Results | Appropriate When |

|---|---|---|

| Power of authority, position, or majority | The conflict may escalate or the other party may withdraw. | There are short time frames and quick action is vital. |

| Power of persuasion | Reduces the quality and durability of agreement. | Dealing with trivial issues. |

| Pressure techniques (e.g., threats, force, intimidation) | Assumes no reciprocating power will come from the other side; people tend to reach for whatever power they have when threatened. | Tough decisions require leadership (e.g., enforcing unpopular rules, cost cutting, discipline). |

| Disguising the issue | Increases the likelihood of future problems between parties. | |

| Tying relationship issues to substantive issues | Restricts communication and decreases trust. | |

| Source: Leadership and Influencing Change In Nursing by Joan Wagner, CC BY 4.0. | ||

Like avoidance, the competing style of conflict is low in cooperation and may be helpful when issues are either trivial or serious in nature and require swift decisions. When individuals have legitimate authority and power to make decisions, it is sometimes necessary that they make a choice without engaging in a collaborative conflict process. While this style of decision-making can be required in some situations, it can lead to problems with trust. Misuse of power and coercive behaviours can also create compliance in the short-term, but these strategies can become a source for future conflict.

Accommodating

Accommodating demonstrates a low commitment to goals and high commitment to relationship. This approach is the opposite of competing. It occurs when a person ignores or overrides their own concerns to satisfy the concerns of the other party. An accommodating approach is used to establish reciprocal adaptations or adjustments. This could be a hopeful outcome for those who take an accommodating approach, but when the other party does not reciprocate, conflict can result. Others may view those who use the accommodating approach heavily as “that is the way they are” and don’t need anything in return. Accommodators typically will not ask for anything in return.

Table 2.4 Accommodating

| Types of Accommodating | Results | Appropriate When |

|---|---|---|

| Playing down the conflict to maintain surface harmony | Builds relationships that will allow you to be more effective in future problem solving | You are flexible on the outcome, or when the issue is more important to the other party. |

| Self-sacrifice | Increases the chances that the other party may be more accommodating to your needs in the future | Preserving harmony is more important than the outcome. |

| Yielding to the other point of view | Does not improve communication | Its necessary to build up good faith for future problem solving. |

| You are wrong or in a situation where competition could damage your position. | ||

| Source: Leadership and Influencing Change In Nursing by Joan Wagner, CC BY 4.0. | ||

People who use this style may fear speaking up for themselves or they may place a higher value on the relationship, believing that disagreeing with an idea might be hurtful to the other person. They will say things such as, “Let’s do it your way” or “If it’s important to you, I can go along with it.” Accommodation may be an effective strategy if the issue at hand is more important to others compared to oneself. Accommodators typically will not ask for anything in return. Accommodators tend to get resentful when a reciprocal relationship isn’t established. Once resentment grows, people who rely on the accommodating approach often shift to a competing approach because they are tired of being “used.” This leads to confusion and conflict.

Compromising

A compromising approach strikes a balance between a commitment to goals and a commitment to relationships. The objective of a compromising approach is a quick solution that will work for both parties. Usually it involves both parties giving up something and meeting in the middle.

Table 2.5 Compromising

| Types of Compromising | Results | Appropriate When |

|---|---|---|

| Splitting the difference | Both parties may feel they lost the battle and feel the need to get even next time. | Time pressures require quick solutions. |

| Exchanging concessions | No relationship is established although it should also not cause relationship to deteriorate. | Collaboration or competition fails. |

| Finding middle ground | Danger of stalemate | Short-term solutions are needed until more information can be obtained. |

| Does not explore the issue in any depth | ||

| Source: Leadership and Influencing Change In Nursing by Joan Wagner, CC BY 4.0. | ||

The compromiser may say things such as, “Perhaps I ought to reconsider my initial position” or “Maybe we can both agree to give in a little.” In a compromise, each person sacrifices something valuable to them. Compromising is often used in labour negotiations, as typically there are multiple issues to resolve in a short period of time.

Collaborating

Collaborating is an approach that demonstrates a high commitment to goals and also a high commitment to relationships. This approach is used in an attempt to meet concerns of all parties. Trust and willingness for risk is required for this approach to be effective.

Table 2.6 Collaborating

| Type of Collaborating | Results | Appropriate When |

|---|---|---|

| Maximizing use of fixed resources | Builds relationships and improves potential for future problem solving | Parties are committed to the process and adequate time is available. |

| Working to increase resources | Promotes creative solutions | The issue is too important to compromise. |

| Listening and communicating to promote understanding of interests and values | New insights can be beneficial in achieving creative solutions. | |

| Learning from each others insight | There is a desire to work through hard feelings that have been a deterrent to problem solving. | |

| There are diverse interests and issues at play. | ||

| Participants can be future focused. | ||

| Source: Leadership and Influencing Change In Nursing by Joan Wagner, CC BY 4.0. | ||

The collaborating style is a strategy to use for achieving the best outcome from conflict—both sides argue for their position, supporting it with facts and rationale while listening attentively to the other side. The objective is to find a win–win solution to the problem in which both parties get what they want. They’ll challenge points but not each other. They’ll emphasize problem solving and integration of each other’s goals. For example, an employee who wants to complete an MBA program may have a conflict with management when he wants to reduce his work hours. Instead of taking opposing positions in which the employee defends his need to pursue his career goals while the manager emphasizes the company’s need for the employee, both parties may review alternatives to find an integrative solution. In the end, the employee may decide to pursue the degree while taking online classes, and the company may realize that paying for the employee’s tuition is a worthwhile investment. This may be a win–win solution to the problem in which no one gives up what is personally important, and every party gains something from the exchange.

Consider This: Communicating in Conflict

Consider the Other Person’s Conflict Approach

There are times when others may take a conflict approach that is not helpful to the situation. However, the only person that you can control in a conflict is yourself. It is important to be flexible and shift your approach according to the situation and the other people with whom you are working. When someone else is taking an approach that is not beneficial to the situation, it is critical to understand what needs underlie the decision to take that approach. Here are a few examples:

- Avoiders may need to feel physically and emotionally safe. When dealing with avoiders, try taking the time to assure them that they are going to be heard and listened to.

- Competitors may need to feel that something will be accomplished in order to meet their goals. When dealing with competitors, say for example, “We will work out a solution; it may take some time for us to get there.”

- Compromisers may need to know that they will get something later. When dealing with compromisers, say for example, “We will go to this movie tonight, and next week you can pick.” (Be true to your word.)

- Accommodators may need to know that no matter what happens during the conversation, your relationship will remain intact. When dealing with accommodators, say for example, “This will not affect our relationship or how we work together.”

- Collaborators may need to know what you want before they are comfortable sharing their needs. When dealing with collaborators, say for example, “I need this, this, and this. . . . What do you need?”

Which Approach to Conflict is Best?

Like much of organizational behavior, there is no one “right way” to deal with conflict. Much of the time it will depend on the situation. However, the collaborative style has the potential to be highly effective in many different situations.

We do know that most individuals have a dominant style that they tend to use most frequently. Think of your friend who is always looking for a fight or your coworker who always backs down from a disagreement. Successful individuals are able to match their style to the situation. There are times when avoiding a conflict can be a great choice. For example, if a driver cuts you off in traffic, ignoring it and going on with your day is a good alternative to “road rage.” However, if a colleague keeps claiming ownership of your ideas, it may be time for a conversation. Allowing such intellectual plagiarism to continue could easily be more destructive to your career than confronting the individual. Research also shows that when it comes to dealing with conflict, managers prefer forcing, while their subordinates are more likely to engage in avoiding, accommodating, or compromising (Howat & London, 1980). It is also likely that individuals will respond similarly to the person engaging in conflict. For example, if one person is forcing, others are likely to respond with a forcing tactic as well.

Self-Assessments

Adapted Works

“Conflict Management” in Organizational Behaivour by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Conflict and Negotiations” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

“Identifying and Understanding How to Manage Conflict” by Dispute Resolution Office, Ministry of Justice (Government of Saskatchewan) in Leadership and Influencing Change in Nursing by Joan Wagner is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

Howat, G., & London, M. (1980). Attributions of conflict management strategies in supervisor-subordinate dyads. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 172–175.

Thomas, K. (1976). Conflict and conflict management. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 889-935). Rand McNally.

Kilmann Diagnostics. (n.d.). Take the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI). https://kilmanndiagnostics.com/overview-thomas-kilmann-conflict-mode-instrument-tki/