7.6 Conflict Management in Today’s Global Society

Conflict Resolution Assessment

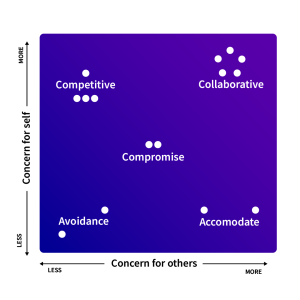

There are five types of conflict styles: avoidance, accommodation, collaboration, competition, and compromise. Each of us has a conflict style that pairs with our personality and our values, beliefs, and experiences. It is possible to have more than one style and the difference of where those styles are more viable can depend on the environment of the conflict.

Example: At work, Susan supervises 3 employees. If there is any disagreement, conflicts, or issues within the team- Susan will work with each individual to address it. At home, when Susan experiences conflict with her mom, Susan will avoid addressing any issue or disagreement.

Let’s review the different types of conflict strategies and then discuss why Susan responds differently in her work at home life.

The graph above shows how higher/lower concern for self and others affects how we manage conflict. High concern for self may include our desire to control others whereas, low concern for self, sees one hiding from the conflict altogether. With high concern for others, one may seek to work together, or with low concern for others seek to give in to demands or needs. Compromise occupies a middle ground, where many may feel they did not get everything they wanted or needed.

Avoidance: “Conflict? What Conflict?”

Strategies of this style include denial, ignoring, and withdrawing. With limited concern for yourself and sometimes others, an individual with this style will avoid addressing any conflicts or issues. One is not committed to standing their ground or that of others. In this case, the person does not feel they get what they want or need and others feel the same. This is seen as a lose-lose approach where both sides never manage or address what causes their conflict. Both may feel unfulfilled or ignored.

When used: When the issue is trivial, outcomes are not necessary.

When not used: When negative feelings may linger, you care about the issue.

Competition: “My way is the only way.”

In contrast to “avoidance,” a competitive style wants to win at any cost with the competitive style. Strategies of this style would include controlling, arguing, outsmarting, and contending. One has high concern for self and little to no concern for others. This style may have one seen as demanding or selfish. Making a stance, when needed, may be warranted; however, if this is a common conflict style, others will feel they are being bullied. This is seen as a win-lose approach to conflict. With this approach, one wins- usually at the expense of the other person. This has the loser feeling short-changed or that needs are being ignored.

When used: Others do not care about what happens.

When not used: Cooperation from others is important, self-respect from others is diminished needlessly.

Accommodation: “Whatever you want is okay with me.”

Strategies to this style include appeasement, agreement, and flattery. Those with accommodation conflict styles have a higher concern for others and less of self. Here, they give into other’s needs and demands and sacrifice their own needs. If chronically using this form of conflict management, others may take advantage of this person. Accommodating individuals will feel they are being taken advantage of and never have their own needs fulfilled.

When used: Issue is not important, realize you are wrong, attempt to “take turns.”

When not used: Likely to resent it, used habitually to gain acceptance.

Collaboration: “Let’s solve this problem together!”

With this type of conflict style, individuals come up with a variety of solutions and the one was chosen is one favoured by both. Strategies for this style would include gathering information, looking for other options, conversation, and agreeing to disagree. Referring back to the restaurant scenario, in this style, individuals choose a restaurant both accept. For example, Jane and Thomas are going out for lunch. Jane, a semi-vegetarian, wants seafood and Thomas, a die hard red meat eater, is craving steak. To collaborate, the two throw out other options and decide to go to an Italian restaurant, instead. Both love Italian food and are happy to give up their initial choice. This win-win approach makes both feel a balanced solution was reached for both sides to feel satisfied.

When used: The issues and/or the relationship are both significant, both want to address all concerns.

When not used: Time and resources are limited, issues are unimportant

Compromise: “Meet me in the middle.”

Strategies for this style of conflict include reducing expectations, negotiating, a little something for all involved. Compromise is keeping others and ones’ own needs into consideration. This may have you give up what you want today- in exchange for another day. Each works for success and happiness. This type is great if used over time and works well with long-term relationships. A good example is two friends agreeing to go to the other’s choice for lunch and the next time going to the second person’s choice. Both get what they want; but, must wait until it is their turn.

When used: Finding a resolution is better than nothing, cooperation is more important but resources are limited.

When not used: You can not live with the consequences.

Triggers and Self-monitoring Enhancement

Unfortunately, none of us have Super Hero powers. We are all simply human. We may stumble on triggers that make us more susceptible to managing conflict in a reactive or negative manner. Knowing your triggers can help reduce bad conflict and redirect to simple good conflict. Below are examples of common triggers that make us more vulnerable to poor conflict outcomes.

- Lack of sleep. When functioning on limited sleep, we become more irritable and likely to over-react to situations.

- Low blood sugar or lack of food. Because our blood sugar levels are lower, our bodies are having to work harder to maintain systems.

- Too hot/cold temperatures. Yes, environment plays a major role in our behaviour. Some may experience irritable states when they become too warm or cold. This also includes other sensory triggers: too much noise, overwhelming smells, too many people around, etc.

- Limited information or not being able to understand information. Perhaps not understanding the vocabulary being used or the accent of the person makes you uncomfortable and more irritable.

- High face-saving. Some cultures see their public image as very important. If they feel disgraced or embarrassed they may become irate.

Understanding your triggers helps monitor yourself/actions in conflict situations and can enhance your reactions in a positive manner. By framing your conflict in a positive direction, knowing when you are emotional, what your triggers are (what sets you off), and seeking out proactive solutions, you can know how to handle conflict.

The PIN Model of Conflict

Adapted from training materials by Derek Emerson, Hope College, 1994.

In conflicts, each person (or group) involved has a PIN: a position, an interest, and a need. PINs often help those working to find a resolution to the conflict because PINs develop into communication channels when determining the similarities and differences between the parties. Being aware of your own PINs and paying attention to the PIN of whom your conflict is with can be helpful.

- Positions. What we state we want

- Interests. What we really want

- Needs. What we must have

Strategies for Handling and Preventing Conflict

There are a variety of approaches or styles to managing conflict, especially when emotionally charged, that individuals may use (Blake & Mouton, 1994). Culture, or an individual’s upbringing, usually reflects how one manages such conflict (Croucher et al, 2012). Knowing how to identify your own conflict styles, needs, and the needs of others will help you to develop better, more rewarding outcomes, and to demonstrate a more ethical perspective.

Our social norms and rituals may create expectations that trigger conflict. Norms are expected behaviours we abide by within groups. These may include our dress, interaction with authorities and elders, social roles (feminine/masculine, parent/child, leader/follower), and verbal/nonverbal communication. By being too loud at a restaurant, disclosing too much personal information, or questioning authority, one might trigger conflict.

Emotions and Our Developing Brain

Though often overlooked, when discussing conflict, extreme reactions of emotional response can be profound, and cause individuals who have not learned to manage conflict proactively and productively to react in a destructive manner (Lindner, 2009). The brain is hardwired to react to conflict. This includes emotional processing through six brain structures (amygdala, basal, ganglia, left prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and orbital frontal cortex). Our brains help us regulate our emotions. As we grow and mature, our brains are better able to reason, drawing more on logic than responding to emotion. This allows us to better understand social norms expected for an adult and to manage conflict more appropriately. Delayed biological development, brain injury, and social environmental factors may lead to less favourable management of conflict (Lindner, 2009). Learning to proactively manage conflict re-enforces successful conflict management, ethical behaviour, and/or collaboration, which in turn can help us feel more at peace.

Conflict management is a uniquely communication-oriented skill, and it is likely that before this class you had not been exposed to the many ways we can understand and resolve conflict in our relationships. Successfully completing a college degree includes how well you manage conflict with your classmates, teachers, family and friends back home, and many other relationships.

It is important to recognize the types of conflicts we encounter on a daily basis, as well as the various strategies or styles for approaching conflict situations. Employers are increasingly seeking applicants who can demonstrate emotional intelligence, which includes an acumen for managing conflict effectively in professional settings. Additionally, it is important to appreciate the positive or generative possibilities of conflict. If you think about out it, some of the best ideas produced by a culture may be forged out of conflict situations. If we commit to conflict management as a life-long learning experience, rather than something to fear, then our personal, professional, and public lives will benefit greatly.

“2.4: Conflict Management in Today’s Global Society” from Communication for Business Professionals by Department of Communication, Indiana State University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.