2.2 Self-Understanding is Fundamental to Communication

You need to know what you want to say before you can say it to an audience. Understanding your perspective can lend insight to your awareness, the ability to be conscious of events and stimuli. Awareness determines what you pay attention to, how you carry out your intentions, and what you remember of your activities and experiences each day. Awareness is a complicated and fascinating area of study. The way we take in information, give it order, and assign it meaning has long interested researchers from disciplines including sociology, anthropology, and psychology.

Your perspective is a major factor in this dynamic process. Whether you are aware of it or not, you bring to the act of reading this sentence a frame of mind formed from experiences and education across your lifetime. Learning to recognize how your perspective influences your thoughts is a key step in understanding yourself and preparing to communicate with others. In the image that follows there are two skydivers that seem to be having a lot of fun. That is their perspective. Perhaps skydiving might not be fun for everyone, it might be quite frightening to some.

Self-Concept

When you communicate, you are full of expectations, doubts, fears, and hopes. Where you place emphasis, what you focus on, and how you view your potential have a direct impact on your communication interactions. You gather a sense of self as you grow, age, and experience others and the world. Much of what you know about yourself you have learned through interaction with others.

The concept of the looking glass self explains that you see yourself reflected in other people’s reactions to you and then form your self-concept based on how you believe other people see you (Cooley, 1922). This reflective process of building your self-concept is based on what other people have actually said, such as “You’re a good listener,” and other people’s actions, such as coming to you for advice. These thoughts evoke emotional responses that feed into your self-concept. For example, you may think, “I’m glad that people can count on me to listen to their problems.”

Carol Dweck, a psychology researcher at Stanford University, states that “something that seems like a small intervention can have cascading effects on things we think of as stable or fixed, including extroversion, openness to new experience, and resilience.” (Begley, 2008) Your personality and expressions of it, like oral and written communication, were long thought to have a genetic component. But, says Dweck, “More and more research is suggesting that, far from being simply encoded in the genes, much of personality is a flexible and dynamic thing that changes over the life span and is shaped by experience.” (Begley, 2008) If you were told by someone that you were not a good listener, know this: You can change. You can shape your performance through experience, and a business communication course, a mentor at work, or even reading effective business communication authors can result in positive change.

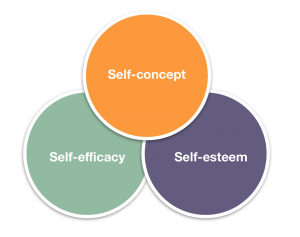

In Figure 2.3 below, the trio of the looking glass self is represented.

Attitudes, Beliefs, and Values

When you consider what makes you you, the answers multiply as do the questions. As a baby, you learned to recognize that the face in the mirror was your face. But as an adult, you begin to wonder what and who you are. While you could explore the concept of self endlessly and philosophers have wrestled and will continue to wrestle with it, for your learning purpose, focus on self, which is defined as one’s own sense of individuality, motivations, and personal characteristics (McLean, 2003). You also must keep in mind that this concept is not fixed or absolute; instead, it changes as you grow and change across your lifetime.

One point of discussion useful for your study about yourself as a communicator is to examine your attitudes, beliefs, and values. These are all interrelated, and researchers have varying theories as to which comes first and which springs from another. You learn your values, beliefs, and attitudes through interaction with others.

- An attitude is your immediate disposition toward a concept or an object. Attitudes can change easily and frequently. You may prefer vanilla while someone else prefers peppermint, but if someone tries to persuade you of how delicious peppermint is, you may be willing to try it and find that you like it better than vanilla.

- Beliefs are ideas based on your previous experiences and convictions and may not necessarily be based on logic or fact. You no doubt have beliefs on political, economic, and religious issues. These beliefs may not have been formed through rigorous study, but you nevertheless hold them as important aspects of self. Beliefs often serve as a frame of reference through which you interpret your world. Although they can be changed, it often takes time or strong evidence to persuade someone to change a belief.

- Values are core concepts and ideas of what you consider good or bad, right or wrong, or what is worth the sacrifice. Your values are central to your self-image, which makes you who you are. Like beliefs, your values may not be based on empirical research or rational thinking, but they are even more resistant to change than are beliefs. To undergo a change in values, a person may need to undergo a transformative life experience.

Self-Image and Self-Esteem

Your self-concept is composed of two main elements: self-image and self-esteem. Your self-image is how you see yourself, and how you would describe yourself to others. It includes your physical characteristics—your eye colour, hair length, height, and so forth. It also includes your knowledge, experience, interests, and relationships. What is your image of yourself as a communicator? How do you feel about your ability to communicate? While the two responses may be similar, they indicate different things.

Your self-esteem is how you feel about yourself; your feelings of self-worth, self-acceptance, and self-respect. Healthy self-esteem can be particularly important when you experience a setback or a failure. High self-esteem will enable you to persevere and give yourself positive messages like “If I prepare well and try harder, I can do better next time.”

Test Your Self-Esteem

Use the following link to participate in a small Psychology Today experiment about self-esteem:

Use the following link to participate in a small Psychology Today experiment about self-esteem:

Activity: Test Your Self-Esteem

Putting your self-image and self-esteem together yields your self-concept: your central identity and set of beliefs about who you are and what you are capable of accomplishing. When it comes to communicating, your self-concept can play an important part. You may find that communicating is a struggle, or the thought of communicating may make you feel talented and successful. Either way, if you view yourself as someone capable of learning new skills and improving as you go, you will have an easier time learning to be an effective communicator. Whether positive or negative, your self-concept influences your performance and the expression of that essential ability: communication.

Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

In a psychology experiment that has become famous through repeated trials, several public school teachers were told that specific students in their classes were expected to do quite well because of their intelligence (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968). These students were identified as having special potential that had not yet “bloomed.” What the teachers didn’t know was that these “special potential” students were randomly selected. That’s right: as a group, they had no more special potential than any other students. Can you anticipate the outcome? As you may guess, the students lived up to their teachers’ level of expectation. Even though the teachers were supposed to give appropriate attention and encouragement to all students, in fact, they unconsciously communicated special encouragement verbally and nonverbally to the special potential students. And these students, who were actually no more gifted than their peers, showed significant improvement by the end of the school year. This phenomenon came to be called the “Pygmalion effect” after the myth of a Greek sculptor named Pygmalion, who carved a marble statue of a woman so lifelike that he fell in love with her—and in response to his love, she did, in fact, come to life and marry him (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968; Insel & Jacobson, 1975).

In more recent studies, researchers have observed that the opposite effect can also happen: when students are seen as lacking potential, teachers tend to discourage them or, at a minimum, fail to give them adequate encouragement. As a result, the students do poorly (Anyon, 1980; Oakes, 1985; Sadker & Sadker, 1994; Schugurensky, 2009).

When people encourage you, it affects the way you see yourself and your potential. Seek encouragement for your writing and speaking. Actively choose positive reinforcement as you develop your communication skills. You will make mistakes, but the important thing is to learn from them. Keep in mind that criticism should be constructive, with specific points you can address, correct, and improve. The concept of a self-fulfilling prophecy, in which someone’s behaviour comes to match and mirror others’ expectations, is not new. Robert Rosenthal, a professor of social psychology at Harvard, observed four principles while studying this interaction between expectations and performance:

- We form certain expectations of people or events.

- We communicate those expectations with various cues, verbal and nonverbal.

- People tend to respond to these cues by adjusting their behaviour to match the expectations.

- The outcome is that the original expectation becomes true.

To summarize, you can become a more effective communicator by understanding yourself and how others view you: your attitudes, beliefs, and values; your self-concept; and how the self-fulfilling prophecy may influence your decisions.

“18. Self-Understanding Is Fundamental to Communication” from Communication for Business Professionals by eCampusOntario is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.