2.1 Perception

Activity: Optical Illusion

Optical illusions are one way of demonstrating how one person’s perception might differ from another’s. In Figure 2.1 below, what can you see?

In the same way that your visual perception can sometimes cause confusion or multiple interpretations, your perceptions related to oral and written communication can also create challenges.

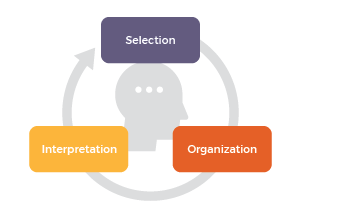

Perception is the process of selecting, organizing, and interpreting information. This process, which is represented in Figure 2.2 below, includes the perception of select stimuli that pass through your perceptual filters, are organized into your existing structures and patterns, and are then interpreted based on previous experiences. How you perceive the people and objects around you affects your communication. You respond differently to an object or person that you perceive favourably than you do to someone (or something) you find unfavourable. But how do you filter through the mass amounts of incoming information, organize it, and make meaning from what makes it through your perceptual filters and into your social realities?

Figure 2.2. Selection, interpretation, and organization contribute to perception.

Figure 2.2. Selection, interpretation, and organization contribute to perception.

Selecting Information

Most people take in information through their five senses, but your perceptual field (the world around you) includes so many stimuli that it is impossible for your brain to process and make sense of it all. So, as information comes in through your senses, various factors influence what actually continues on through the perception process (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). Selecting is the first part of the perception process, in which you focus your attention on certain incoming sensory information. Think about how, out of many other possible stimuli to pay attention to, you may hear a familiar voice in the hallway, see a pair of shoes you want to buy from across the mall, or smell something cooking for dinner when you get home from work. You quickly cut through and push to the background all kinds of sights, smells, sounds, and other stimuli, but how do you decide what to select and what to leave out?

Watch the following 2-minute video: The Monkey Business Illusion.

Video: The Monkey Business Illusion by Daniel Simons [1:41] transcript available.

You tend to pay attention to information that is salient. Salience is the degree to which something attracts your attention in a particular context. The thing attracting your attention can be abstract, like a concept, or concrete, like an object. Did you notice the person in the monkey suit while watching the video above? It was subtle. A bright flashlight shining in your face while camping at night is sure to be salient. The degree of salience depends on three features according to Fiske & Taylor (1991) whether the object is visually or aurally stimulating, whether it meets your needs or interests, and whether it meets or challenges your expectations.

- Visual and Aural Stimulation – It is probably not surprising to learn that visually and/or aurally stimulating things become salient in our perceptual field and get our attention.

- Needs and Interests – We tend to pay attention to information that we perceive to meet our needs or interests in some way. We also find salient information that interests us.

- Expectations – The relationship between salience and expectations is a little more complex. Basically, we can find expected things salient and find things that are unexpected salient.

As a communicator, you can use this knowledge about salience to your benefit by minimizing distractions when you have something important to say. It’s probably better to have a serious conversation with a significant other in a quiet place rather than a crowded food court. Aside from minimizing distractions and delivering your messages enthusiastically, the content of your communication also affects salience. Whether a sign helps you find the nearest gas station, the sound of a ringtone helps us find your missing cell phone, or a speaker tells you how avoiding processed foods will improve your health, you select and attend to information that meets your needs.

Likely you have experienced the sensation of being engrossed in a television show, video game, or random project that you paid attention to at the expense of something that actually met your needs – like cleaning or spending time with a significant other. Paying attention to things that interest you but don’t meet specific needs seems like the basic formula for procrastination that you might be familiar with.

If you are expecting a package to be delivered, you might pick up on the slightest noise of a truck engine or someone’s footsteps approaching your front door. Since you expect something to happen, you may be extra tuned in to clues that it is coming. In terms of the unexpected, if you have a shy and soft-spoken friend who you overhear raising the volume and pitch of his voice while talking to another friend, you may pick up on that and assume that something out of the ordinary is going on. For something unexpected to become salient, it has to reach a certain threshold of difference. If you walked into your regular class and there were one or two more students there than normal, you may not even notice. If you walked into your class and there was someone dressed up as a wizard, you would probably notice. So, if you expect to experience something out of the routine, like package delivery, you will find stimuli related to that expectation salient. If you experience something that you weren’t expecting and that is significantly different from your routine experiences, then you will likely find it salient. You can also apply this concept to your communication. Good instructors encourage their students to include supporting material in their speeches that defies audience expectations. You can help keep your audience engaged by employing good research skills to find such information.

Organizing Information

Organizing is the second part of the perception process, in which you sort and categorize information that you perceive based on innate and learned cognitive patterns. Three ways you sort things into patterns are by using proximity, similarity, and difference (Coren & Girgus, 1980).

- Proximity – In terms of proximity, we tend to think that things that are close together go together.

- Similarity – We also group things together based on similarity. We tend to think similar-looking or similar-acting things belong together.

- Difference – We also organize information that we take in based on differences. In this case, we assume that the item that looks or acts differently from the rest doesn’t belong to the group.

Since you often organize perceptual information based on proximity, you may automatically perceive that two people are together, just because they are standing close together in a line.

This type of strategy for organizing information is so common that it is built into how you function in your daily life. If you think of the literal act of organizing something, like your desk at home or work, you follow these same strategies. If you have a bunch of papers and mail on the top of your desk, you will likely sort papers into separate piles for separate classes or put bills in a separate place than personal mail. You may have one drawer for pens, pencils, and other supplies and another drawer for files. In this case, you are grouping items based on similarities and differences. You may also group things based on proximity, for example, by putting financial items like your chequebook, a calculator, and your pay stubs in one area so you can update your budget easily. In summary, you simplify information and look for patterns to help conduct tasks and communicate efficiently in all aspects of your life.

Simplification and categorizing based on patterns isn’t necessarily a bad thing. In fact, without this capability, you would likely not have the ability to speak, read, or engage in other complex cognitive/behavioural functions. There are differences among people, and looking for patterns helps you in many practical ways. However, the judgments you might place on various patterns and categories are not natural; they are learned and culturally and contextually relative. Your perceptual patterns do become unproductive and even unethical when the judgments you associate with certain patterns are based on stereotypical or prejudicial thinking.

Interpreting Information

Although selecting and organizing incoming stimuli happens very quickly, and sometimes without much conscious thought, interpretation can be a much more deliberate and conscious step in the perception process. Interpretation is the third part of the perception process, in which you assign meaning to your experiences using mental structures known as schemata. Schemata are like databases of stored, related information that you use to interpret new experiences. Schemata are like lenses that help you make sense of the perceptual cues around you based on previous knowledge and experience.

It’s important to be aware of schemata because your interpretations affect your behaviour. For example, if you are doing a group project for class and you perceive a group member to be shy based on your schema of how shy people communicate, you may avoid giving him or her presentation responsibilities because you do not think shy people make good public speakers. Schemata also guide your interactions, providing a script for your behaviours. Many people know how to act and communicate in a waiting room, in a classroom, on a first date, and on a game show. Even a person who has never been on a game show can develop a schema for how to act in that environment by watching The Price Is Right, for example. A final example, you often include what you do for a living in your self-introduction, which then provides a schema through which others interpret your communication.

“17. Perception” from Communication for Business Professionals by eCampusOntario is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.