21.3 Changes in Accounting Estimates

As we have seen in previous chapters, many accounting assertions require the use of estimates. Some more common estimates include the useful life of a piece of equipment, the percentage of accounts receivable that are expected to be uncollectible, and the net realizable value of obsolete inventory. The use of estimates is considered to be a normal part of the accounting process, and it is presumed that the accountant, when making an estimate, will take into account all the relevant information that is available at that time. However, new information can become available in later accounting periods that will cause accountants to reconsider their original estimates. If this information was not available at the time of the original estimate, it would be inappropriate to go back and restate prior period financial results. As such, changes in accounting estimates are treated prospectively, meaning financial results are adjusted to reflect the new information in the current year and in future periods. No attempt is made to determine the effect on prior years, and no adjustment to opening balances is necessary.

Consider the following example. Umbach Inc. purchased a machine to be used in its manufacturing facility on January 1, 2020. The machine cost $120,000 and was expected to be used for eight years, with no residual value. On January 1, 2022, an engineering review of the machine’s performance indicated that its useful life is now six years instead of eight.

The machine would have been originally depreciated at $15,000 (![]() ) per year. Thus, on January 1, 2022, the carrying amount of the machine would have been $90,000 (

) per year. Thus, on January 1, 2022, the carrying amount of the machine would have been $90,000 (![]() ). On January 1, 2022, the remaining useful life is now four years (

). On January 1, 2022, the remaining useful life is now four years (![]() ). The new depreciation amount will therefore be $22,500 (

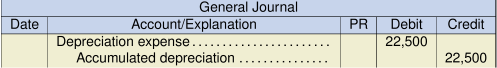

). The new depreciation amount will therefore be $22,500 (![]() ) per year. On December 31, 2022, the following journal entry will be made:

) per year. On December 31, 2022, the following journal entry will be made:

Note that we are simply recording the new depreciation amount in the normal fashion without making any attempt to restate prior depreciation amounts. This is the essence of prospective application: simply recalculating the amount based on the new information, and using this amount for current and future years only.

In some cases, however, it may not be clear if a change is a change in estimate or a change in policy. For example, changing from straight-line depreciation to declining balance depreciation may appear to be a change in policy. However, this change might, in fact, reflect a revision of management’s view of how the pattern of benefits is being derived from the asset’s use. In this case, the change would be treated as a change in estimate. If it is not clear whether a change is change in policy or a change in estimate, IAS 8 suggests that the change should be treated as a change in estimate.