20.1 Financial Reports: Overview

As discussed in previous chapters, shareholders, potential investors, and creditors use published financial statements to assess a company’s overall financial health. Recall how the five core financial statements link together into a cohesive network of financial information. One of these links is the match between the ending cash balance reported in the statement of cash flows (SCF) and the ending cash balance in the statement of financial position (IFRS), or balance sheet (ASPE).

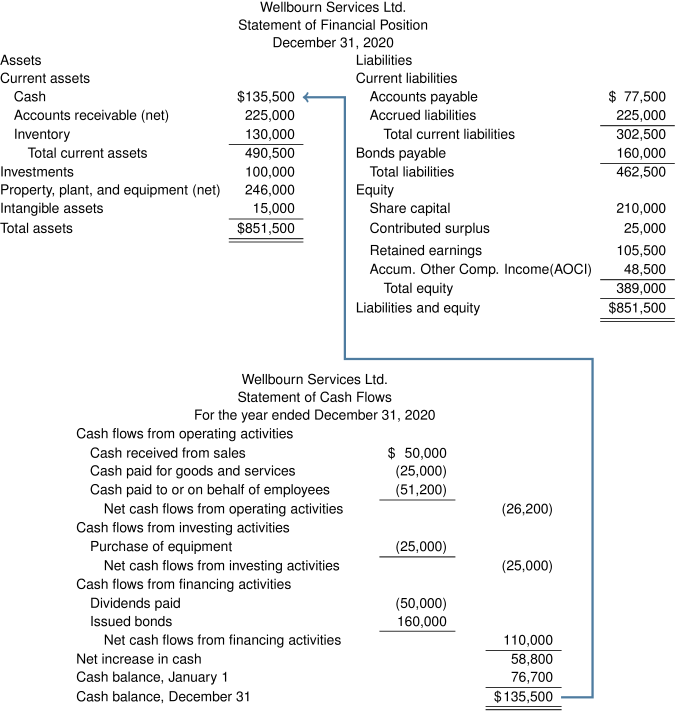

For example, below is the statement of cash flows for the year ended December 31, 2020, and the statement of financial position (SFP) for Wellbourn Services Ltd. at December 31, 2020.

Note how Wellbourn’s ending cash balance of $135,500, from the statement of cash flows for the year ended December 31, matches the ending cash balance in the SFP on that date. This is a critical relationship between these two financial statements. The SFP provides information about a company’s resources (assets) at a specific point in time, and whether these resources are financed mainly by debt (current and long-term liabilities) or equity (shareholders’ equity). The statement of cash flows identifies how the company utilized its cash inflows and outflows over the reporting period and, ultimately, ends with its current cash and cash equivalents position at the statement of financial position date. As well, since the statement of cash flows is prepared on a cash basis, it excludes non-cash accruals like depreciation and interest, making the statement of cash flows harder to manipulate than the other financial statements.

Since the statement of cash flows separates cash flows into those resulting from ongoing operating activities versus investing and financing activities, investors and creditors can quickly see where the main sources of cash originate. If cash inflows are originating mainly from operating activities, then this provides insight into a company’s ability to generate sufficient cash to maintain its operations, pay its debts, and make new investments without the need for external financing. If cash sources originate more from investing activities, then this means that the company is likely selling off some of its assets to cover its obligations. This may be appropriate if these assets are idle and are no longer generating profit; otherwise it may suggest a downward spiral resulting in plummeting profits. If cash sources are originating mainly from financing activities, then the company is likely sourcing more cash from debt or from issuing shares (equity). Higher debt means that more cash reserves are needed to make the principal and interest payments. Higher equity means more shares issued and more dividends to be paid out, not to mention the dilution of existing shareholders investments. Either scenario is cause for concern for both shareholders and creditors.

Even if the majority of cash inflows are mainly from operating activities, if there is a large difference between net income and the total cash inflows from operating activities then that is a warning sign that shareholders and creditors should be digging deeper. This is because a company’s quality of earnings, and hence its reliability, relates to how closely reported net income corresponds to net cash flows. For example, if reported net income is consistently close to, or less than, net cash operating activities, the company’s earnings are considered to be high quality and, therefore, reliable. Conversely, if reported net income is significantly more than net cash flows from operating activities, then reported net income is not matched by a corresponding increase in cash, creating a need to investigate the cause. After reviewing the statement of cash flows and the balance sheet, the bottom line is: if debt is high and cash balances are low, the greater the risk of business failure.

This chapter will explain how to prepare the statement of cash flows using either the direct or indirect method, and how to interpret the results.