16.4 Defined Benefit Plans

Defined benefit plans are the opposite of defined contribution plans. With a defined benefit plan, the amount of pension income the employee will receive upon retirement is defined either as a pre-determined amount or by calculation using a prescribed formula. Because the ultimate payment from the plan is defined, the risks of the plan now fall upon the employer. If the plan fails to retain sufficient assets to pay out the defined pension benefits, the employer is required to make up the difference through additional contributions. As noted in the example of Bombardier, this amount can be significant.

An important concept of defined benefit plans is that of vesting. Vesting refers to the principle that employees are entitled to receive certain benefits even if they cease to be employed by the company. Non-vested benefits are those that are lost once the employee ceases to provide service to the employer. With pension plans, there is usually a minimum term of service that is required before the pension benefits will vest.

Because the employer is responsible for the defined benefit that the pension plan will ultimately pay out, the accounting becomes more complicated. This is because the existence of the defined benefit creates a liability to the company. The liability represents the present value of future cash flows related to the payment of pensions to retired employees. Offsetting this liability are the assets held by the trustee in the pension plan.

Although it is fairly easy to determine the fair value of the assets held by the trustee, it is not as simple to determine the present value of future pension payments. A number of assumptions and estimates are required to make this determination, including:

- When will the employee retire?

- How long will the employee live after retirement?

- What level of salary will the pension payments be based on?

- What return will be earned on the plan assets in the future?

- What discount rate is appropriate for the present value calculation?

Accountants generally don’t have the specialized knowledge or expertise to make these kinds of estimates. However, a particular group of professionals called actuaries can help with this process. Actuaries are trained in statistical sciences and they understand how to use existing data to make these kinds of determinations. Because pension payments are often made far in the future, and are based on unknowable factors such as an employee’s lifespan, there is the potential for estimation error. As such, an accountant will often review the work of the actuary to ensure it is appropriate for financial reporting purposes. Although IAS 19 does not require the use of actuaries, it is unlikely that an accountant would have sufficient technical knowledge to carry out these calculations on his or her own, except in the case of the most basic pension plan arrangements.

So what exactly does the actuary measure? The main focus of the actuary’s work is called the defined benefit obligation (DBO). This represents the present value of all future pension payments for current employees, based on their expected salaries at the time they retire. This calculation takes into account all service provided by the employees up to the reporting date, but it does not include future service. However, a key assumption is that the pension plan will continue to operate and employees will continue to work until their expected retirement date. This calculation requires estimations regarding employee turnover, inflation, and other factors affecting future salaries, such as expected retirement dates and mortality. Note that this calculation also includes estimates related to unvested benefits, as it is expected that the benefits will vest to the employees in the normal course of their employment.

The balance of the defined benefit obligation will be affected by a number of factors each year:

- Current service cost

- Interest on the obligation

- Benefits paid to retirees

- Past service costs and plan amendments

- Actuarial gains and losses

Current service cost is an essential element to the pension obligation. It represents the present value of future benefits required to be paid to current employees, based on the service they have provided in the current accounting period. This amount is estimated by the actuary, taking into account the formula for calculating the pension entitlement, the expected number of years until retirement, and other actuarial factors. The amount is calculated using the projected unit credit method, which allocates the ultimate pension benefit payable in roughly equal proportions over the employee’s working life. This present value technique, thus, will take into account the effect of future salary increases on the current service obligation.

The interest cost on the obligation is a basic concept that reflects the time value of money. Because the payments to retirees will be made in the future, the obligation must be discounted to its present value. As time passes, interest must be accrued on the obligation during each accounting period, increasing the obligation’s carrying value each period until it reaches the ultimate amount payable to the employee on the date of retirement. Although the correct accounting treatment requires calculation of the interest cost based on actual transactions in the plan during the year, a simplifying assumption we will make is that transactions occur at the end of the year. This means that, unless otherwise stated, we will assume that the interest cost is based on the opening balance of the DBO.

The third essential element in the calculation of the DBO is the value of benefits paid to retirees. As these benefits are paid, the obligation is reduced because the company is fulfilling its obligation to its employees under the plan. These payments will reduce the outstanding present value otherwise calculated.

Sometimes a pension plan may be amended or additional pension entitlements granted. This could occur, for example, when a company first commences a new pension plan and wants to grant entitlement to long-serving employees for their service prior to the start of the plan. Or, with an existing plan, the company may want to grant additional pension entitlements to certain groups of employees, such as those who have joined the company through a merger. It is also possible that a company could reduce future pension benefits payable to employees, such as through a renegotiation of collective agreements with unions resulting from reorganization or other type of financial distress. Whatever the reason, the change in the future benefits resulting from past service costs must be adjusted and reflected in the DBO.

The last element of the DBO is perhaps the most difficult to determine. Actuaries, as noted before, are trained in analyzing and using various types of data to make their predictions and calculations of the DBO. However, predicting the future is imprecise and sometimes the actuary will need to change the projected amounts based on new calculations. These new calculations could result from observations of actual patterns that are different from what was previously predicted, or from completely new data that changes the existing assumptions. For example, if during the year there was a significant turnover of employees and the new group is significantly younger than the previous group, the calculation of the DBO would change. Similarly, if new scientific data were released showing that, on average, people are now living longer due to improved health-care services, the DBO would have to be adjusted. Changes in actuarial assumptions are a normal part of the process of estimating the DBO, resulting in actuarial gains or losses during the period.

Aside from the DBO, the other major element of the pension plan is the assets the pension plan holds in trust for the employees. The assets are typically held in a separate entity from the company and are usually legally restricted in a way that prevents their conversion for use in settlement of other non-pension liabilities of the company. The plan assets will usually be held in low-risk investments such as high-quality debt and equity securities, stable real estate properties, cash and other cash equivalents. The goal of the plan is to earn a reasonable return without taking too much risk. However, even a prudent investment strategy can be mismanaged, as discovered by pension fund managers after the 2008 financial crisis, who found that some of the double and triple-A securities they had invested in were not as sound as first believed.

There are three determinants of the value of the pension plan assets:

- Contributions by the employer, and in some cases, the employee

- The actual return on the assets

- Benefits paid to retirees

Contributions are payments made by the employer to the plan based on agreed upon amounts. This would typically be an amount determined by the actuary and is often based on a percentage of employee salaries. In some cases, the employees will also contribute their own money to the plan. This is referred to as a contributory plan. The amount the employee contributes will often be based on tax legislation in the relevant jurisdiction.

The return on the plan’s assets consists of various types of investment returns, such as interest, dividends, and gains and losses on the disposal of plan assets (less any administration fees charged by the pension plan manager). Additionally, IAS 19 requires the plan’s assets to be valued at their fair values, meaning that unrealized gains and losses will also be included in the final balance. Because certain investment markets can be volatile, the actual return earned on the assets from year to year can vary significantly. However, most plan managers will attempt to diversify their portfolios and apply prudent investment strategies to minimize this risk.

As noted previously, actual pension benefits paid to retirees reduce the obligation of the plan. However, they also reduce the assets in the plan.

Finally, the plan assets and the defined benefit obligation (DBO) are not reported on the financial statements of the company. The over or under funded amount is the only item to be reported. Over-funded means that there are more plan assets than obligation. Under-funded means the obligation is higher than the plan assets.

16.4.1. Accounting for Defined Benefit Plans

Although there are a number of complex elements that comprise defined benefit pension plans, the accounting concern of the company reporting under IFRS is simpler. On the sponsoring company’s accounting records, only four relevant accounts need to be considered: the pension expense that will be recorded each year, the net defined benefit asset or liability that will appear on the balance sheet, the cash that is contributed to the plan, and the company’s other comprehensive income (OCI). We will examine how each of these accounts is affected by the pension plan transactions.

It is important to note that the pension plan assets and obligation are not recorded anywhere on the sponsoring company’s financial statements, as these are held by the trustee in the pension plan. Changes in the pension plan’s obligation and assets are, however, accounted for indirectly on the sponsoring company’s financial statements. This is done in the following manner:

- Current and past service costs are reported in net income.

- Net interest is reported in net income.

- Gains and losses from re-measurements of the net asset or liability are reported in other comprehensive income.

- Cash contributions to the plan reduce the company’s liability.

This treatment will result in a net defined benefit expense being reported on the income statement (an adjustment to OCI) and an amount, the net defined benefit liability, being reported on the balance sheet equal to the net difference between the DBO and the fair value of the plan assets. One important point to note in the accounting treatment is the manner in which interest is recorded. Interest on the DBO should be calculated using an appropriate interest rate, which IAS 19 suggests should be a market-based interest rate that is comparable to the current yield on high-quality debt instruments, such as corporate bonds. The rate used would normally be the rate present at the end of the reporting period. A further requirement of IAS 19 is that the interest rate used to discount the DBO should also be used to calculate the return on the plan assets. In other words, the interest cost is calculated only on the net balance of the obligation. The result of using the same interest rate for determining the return on plan assets is that there will likely be a difference between the calculated amount and the actual return on the assets. This difference is accounted for in OCI, much in the same manner as remeasurement gains or losses resulting from changes in actuarial assumptions.

The accounting treatment for pensions under ASPE is slightly different. These differences will be explained in 16.9 Appendix A.

The accounting treatment under IFRS is best illustrated with an example. Consider the following facts: Ballard Ltd. initiated a defined benefit pension plan in 2015. On January 1, 2020, the balance of the DBO as determined by an actuary was $535,000, and the fair value of the plan assets was $500,000.

The following information relates to the three-year period 2020 to 2022:

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current service cost for the year | $57,000 | $65,000 | $76,000 |

| Interest rate on corporate bonds | 8% | 8% | 9% |

| Actual earnings on plan assets | 43,000 | 35,000 | 70,000 |

| Employer contributions | 50,000 | 55,000 | 60,000 |

| Benefits paid to retirees | 20,000 | 23,000 | 25,000 |

| Actuarial gain due to change in assumptions | – | 16,000 | – |

| Cost of past service benefits granted on January 1, 2022 | – | – | 62,000 |

An easy way to understand the accounting for pension plan transactions is to use a worksheet. The worksheet can help organize the relevant data and provides reconciliation between the company’s records and the amounts held in the pension plan. The worksheet format that we will use is comprised of two parts. The left-hand portion represents the amounts held in the pension plan. These are not accounted for directly in the company’s records. The right-hand side of the worksheet represents the company’s accounting records. The data on this side can be used to directly generate the journal entries required and also provides a way to compare the company’s records to those of the pension plan. In our worksheet we will use Debit (DR) and Credit (CR) notations even though the company does not directly record all parts of the worksheet. The use of DR and CR will help us understand how to reconcile the pension plan and company records.

Let’s start with the worksheet for 2020:

| Pension Plan | Company Accounting Records | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBO | Plan Assets | Net Defined Benefit Balance | Cash | Annual Pension Expense | OCI | |

| Opening balance | 535,000 CR | 500,000 DR | 35,000 CR | |||

| Service cost | 57,000 CR | 57,000 DR | ||||

| Interest: DBO[1] | 42,800 CR | 42,800 DR | ||||

| Interest: assets[2] | 40,000 DR | 40,000 CR | ||||

| Contribution | 50,000 DR | 50,000 CR | ||||

| Benefits paid | 20,000 DR | 20,000 CR | ||||

| Remeasurement | 3,000 DR | 3,000 CR | ||||

|

gain: assets[3] |

||||||

| Journal entry | 6,800 CR | 50,000 CR | 59,800 DR | 3,000 CR | ||

| Closing balance | 614,800 CR | 573,000 DR | 41,800 CR | |||

There are a few key points to note from the worksheet:

- The net defined benefit balance at the start of the year represents the amount the company would report on its balance sheet. It also represents the difference between the opening balances of the DBO and the plan assets.

- The interest on the DBO and the plan assets is calculated by simply taking the appropriate interest rate and multiplying it by the opening balance of each item. This calculation has assumed that all pension transactions occur at the end of the year. In practice, pension transactions may occur throughout the year. In that case, interest would need to be calculated on the weighted-average balance in each account.

- Benefits paid to retirees do not affect the company’s accounting records, as these transactions occur between the pension plan and the retirees directly.

- The remeasurement gain represents the difference between the interest calculated on the plan asset balance and the actual return earned by those assets during the year. This gain is taken directly to other comprehensive income.

From this worksheet, the company would make the following journal entry:

The result of this journal entry is a credit of $6,800 to the net defined benefit liability that is reported on the company’s balance sheet. This agrees with the calculation on the worksheet. In practice, the part of the journal entry reflecting the cash contributions by the company would be recorded throughout the year as the company remits pension payments to the plan. On the company’s balance sheet, a net defined benefit liability of $41,800 would be disclosed. This would usually be disclosed as a non-current liability, as it is not normal for a pension liability to be settled within the next year. This balance also represents the net underfunding of the plan at the end of the year. This means that the pension plan does not have sufficient assets to settle the future expected liability for pension payments. In the short term this is not really a problem, as the pension plan payments will occur over a period of many years and it is possible to correct an underfunded plan over time. However, if a pension plan remains chronically underfunded, this may result in problems making payments to retirees. With a defined benefit plan, the sponsoring company will ultimately be responsible for making up this difference, although employees may also be asked to contribute if the plan is contributory. The plan could also be overfunded, which would mean that the fair value of the plan assets exceeds the DBO. This excess amount belongs to the sponsoring company, although legal requirements may prevent the company from withdrawing the amount from the plan. Usually, the excess would be recovered through a reduction of future contributions.

The company would also disclose a pension expense of $59,800 on the income statement and a $3,000 credit to other comprehensive income. There are further disclosure requirements, which are detailed later in this chapter.

Let’s now look at the 2021 transactions:

| Pension Plan | Company Accounting Records | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBO | Plan Assets | Net Defined Benefit Balance | Cash | Annual Pension Expense | OCI | |

| Opening balance | 614,800 CR | 573,000 DR | 41,800 CR | |||

| Service cost | 65,000 CR | 65,000 DR | ||||

| Interest: DBO[4] | 49,184 CR | 49,184 DR | ||||

| Interest: assets[5] | 45,840 DR | 45,840 CR | ||||

| Contribution | 55,000 DR | 55,000 CR | ||||

| Benefits paid | 23,000 DR | 23,000 CR | ||||

| Remeasurement | 10,840 CR | 10,840 DR | ||||

|

loss: assets[6] |

||||||

| Remeasurement | 16,000 DR | 16,000 CR | ||||

|

gain: DBO |

||||||

| Journal entry | 8,184 CR | 55,000 CR | 68,344 DR | 5,160 CR | ||

| Closing balance | 689,984 CR | 640,000 DR | 49,984 CR | |||

The process used is the same as was applied in 2020. However, note one additional difference in 2021: the actuary revised some of the actuarial assumptions. This could result from new data regarding life expectancy, changes in assumptions about expected period of service of employees, changes in assumptions about future wage levels, and several other factors. The change in the assumptions has resulted in an actuarial gain, which means the present value of the future pension payments (and thus, also the DBO) has been reduced. This reduction to the DBO has been recorded as a credit to other comprehensive income and does not directly affect the pension expense recorded. In this example, we have assumed that the change in assumptions occurred at the end of the year. If the change occurred at some other time during the year, the interest calculation would need to be adjusted to reflect weighted average DBO balance throughout the year.

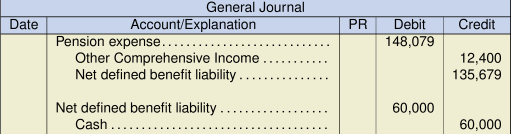

As before, the company will make the following journal entry:

As a result of this journal entry, the company will now report a net defined benefit liability of $49,984 on the balance sheet, representing a net underfunded position.

In 2022, the pension worksheet looks like this:

| Pension Plan | Company Accounting Records | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBO | Plan Assets | Net Defined Benefit Balance | Cash | Annual Pension Expense | OCI | |

| Opening balance | 689,984 CR | 640,000 DR | 49,984 CR | |||

| Past service | 62,000 CR | 62,000 DR | ||||

| Service cost | 76,000 CR | 76,000 DR | ||||

| Interest: DBO[7] | 67,679 CR | 67,679 DR | ||||

| Interest: assets[8] | 57,600 DR | 57,600 CR | ||||

| Contribution | 60,000 DR | 60,000 CR | ||||

| Benefits paid | 25,000 DR | 25,000 CR | ||||

| Remeasurement | 12,400 DR | 12,400 CR | ||||

|

gain: assets[9] |

||||||

| Journal entry | 75,679 CR | 60,000 CR | 148,079 DR | 12,400 CR | ||

| Closing balance | 870,663 CR | 745,000 DR | 125,663 CR | |||

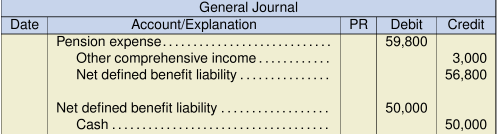

Note that the cost of additional pension benefits granted to employees based on their past service has been immediately expensed. This amount represents the increase in the DBO calculated by the actuary as a result of giving the employees these benefits. The granting of these entitlements is treated as a new event, so it would not be appropriate to adjust prior periods for the additional amount. It would also be inappropriate to capitalize this amount as the employee service that has generated the benefit has already occurred (i.e., there is no future benefit to the company). The result is a significantly larger pension expense in the current year. The company will also report a significantly higher liability, $125,663, on its balance sheet.

The company will make the following journal entry in 2022:

16.4.2. Net Defined Benefit Asset

In our examples, the net defined benefit balance was always in a credit position, meaning the plan was underfunded. However, a plan can be overfunded as well, meaning the fair value of the assets held in the plan exceeds the actuarially determined present value of the DBO. This doesn’t create any particular accounting problem, as the amount would simply be reported as an asset on the sponsoring company’s balance sheet. However, IAS 19 requires that the balance of an overfunded plan be reported at the lesser of:

- The amount of the surplus (the overfunding in the plan)

- The asset ceiling

The asset ceiling is defined as the present value of “future economic benefits available to the entity in the form of a reduction in future contributions or a cash refund, either directly to the entity or indirectly to another plan in deficit” (CPA Canada, 2016, IAS 19.65.c). The present value would be determined using the same interest rate as was used in the pension expense calculations. This provision ensures that the net asset reported under the plan does not exceed the present value of the amount that is reasonably expected to be recovered from the overfunded plan.

- Interest on DBO = $535,000 × 8% = $42,800 ↵

- Interest on assets = $500,000 × 8%= $40,000 ↵

- Remeasurement gain = $43,000 (actual earnings) – $40,000 (calculated above) = $3,000 ↵

- Interest on DBO = $614,800 × 8% = $49,184 ↵

- Interest on sales = $573,000 × 8% = $45,840 ↵

- Remeasurement loss = $35,000 (actual earnings) – $45,840 (calculated above) = $10,840 ↵

- Interest on DBO =($689,984 + $62,000) × 9% = $67,679[/latex] ↵

- Interest on assets = $640,000 × 9% = $57,600 ↵

- Remeasurement gain = $70,000 (actual earnings) – $57,000 (calculated above) = $12,400 ↵