14.4 Options, Warrants, Forwards, and Futures

Options, warrants, forwards, and futures are all examples of derivatives. Derivatives are financial instruments whose value is derived from some underlying instrument, object, index, or event (an “underlying”). Put another way, a derivative represents a contract arising between two or more parties based upon the underlying. Its value is determined by fluctuations in the underlying, and as they have their own value, they can be bought and sold. Reasons for buying or selling may be to minimize risk (hedging) or to make a profit (speculation).

A hedge is an investment, such as a futures contract, whose value moves in an offsetting manner to the underlying asset. Hedging is comparable to taking out an insurance policy, for example, when homeowners in a fire-prone area takes out insurance policies to protect themselves from loss in the event of fire. There is a risk/reward trade-off inherent in hedging as it both reduces potential risk and carries an associated cost, such as the fire insurance policy premiums. That said, most homeowners choose to take that predictable loss by paying insurance premiums rather than risk the loss.

Managing foreign exchange rates provides another example of hedging. Fluctuations in foreign exchange rates can be either advantageous or detrimental to businesses depending on whether the exchange rate increases or decreases, and if the business is exporting or importing goods or services. For example, companies buying goods from another country on credit when the domestic currency exchange rate is rising, or selling goods to another country on credit when the foreign country’s currency is rising, can reap significant gains. However, the opposite can also occur if the rates are decreasing, causing company profits to plummet. Companies can lower these risks by entering into a derivative contract to buy foreign currency at a future date at a specified exchange rate, thereby locking in the purchase price to a known quantity of foreign currency. In this way, a company can manage the risks associated with changes in the foreign exchange rates through hedging.

Speculation regarding derivatives is an effort to make a profit from an unknown outcome. Continuing with the example of foreign currency, if the change in foreign exchange rates favours the speculator, a profit can be made.

Options, warrants, forwards, and futures are all types of derivatives and each one is summarized below. An in-depth discussion of derivatives is covered in a more advanced accounting course.

Options

Call options give the options holder the right to buy an underlying instrument, such as common shares, at a specified price within a specified time frame. The options price is called the exercise, or strike, price and the option must be in the money. That is, the market price must be greater than the exercise price so that the options holder will benefit from exercising the options held. Call options are the most common type of option and employee stock options are a good example. Stock options will be discussed in the next section of this chapter and in the Chapter 19.

Put options are the opposite of call options, because they give the options holder the right to sell common shares at a specified price within a specified time frame back to the issuing company. If the market price of the shares should decline, the option holder can still sell their shares back to the issuing company at the higher specified price.

A written option is when a company sells options in exchange for giving the option holder the right to purchase the underlying shares at a future date. A written option represents an obligation to the company to issue the shares, if called by the option holder or redeem the shares if put by the option holder. For this reason, it is a liability to the company because of the obligation created. Conversely, a purchase option is when a company pays to purchase options giving the company the right to buy (call) or sell (put) the underlying shares from another company, at a future date, if they choose. There is a choice, so no obligation exists to the company holding the call or put options and therefore no liability to record.

Options have their own value which can increase or decrease in response to the changes in market value of the underlying instruments, such as shares. If the market value of shares increase, the options fair value will also increase. Options are to be remeasured to their fair value through net income at each reporting date. If the options are sold in the marketplace without exercising them for shares, any gain or loss upon sale is recorded to net income, and the options derivatives are removed from the books.

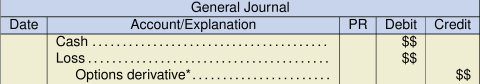

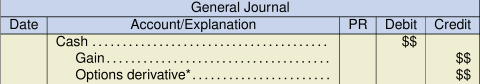

Insert journal entry:

* Reported as either a financial asset or liability depending on if the account has a debit or credit balance.

If the options are exercised, the investment in shares is recorded as a debit, in addition to the entry shown above.

Warrants

Warrants are similar to call options except that they are only issued by the company itself and usually have longer time frames than options. Unlike options, warrants are usually attached to another financial instrument, such as bonds and shares.

Forward Contracts

With forward contracts, both contract parties make a commitment in advance to buy or sell something to each other at a mutually agreed-upon price at a future date. A common example is the purchase or sale of goods in foreign currencies between a supplier and a manufacturer.

Note that once the terms have been agreed upon, and the maturity date occurs, there is no option out of a forward contract. Also, for the contract to be acceptable to both parties, the two parties must hold opposite views as to what will happen to the underlying instrument, for example whether a currency exchange rate will increase or decrease. A forward contract can be privately negotiated and, if the two parties agree to the terms, price, and future date, a forward contract is considered to exist between them.

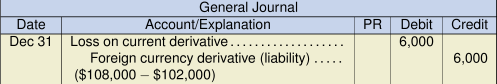

As an example, on November 15, Monnard Inc. agrees to buy $100,000 USD from Oncore Ltd. over the next 90-day period for $108,000 CAD. As nothing is exchanged upon the contract issuance, no accounting entry is required. However, on December 31, the company year-end, the exchange rate has changed, and $100,000 USD is now worth only $102,000 CAD. Despite this, Monnard Inc. is still committed to pay the agreed-upon price of $108,000 CAD and, therefore, a loss has occurred. The derivative must be remeasured to fair value at the reporting date and Monnard Inc. must record a loss as follows:

In contrast, Oncore Ltd. will record a corresponding gain and debit a foreign currency derivative asset account.

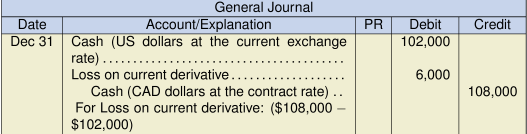

However, if Monnard Inc. actually purchased the $100,000 USD on December 31, the entry would include both the remeasurement to fair value loss of $6,000 as well as a credit to cash in a combined entry:

Futures Contracts

These contracts are like forwards contracts except that they are highly standardized in terms of price and maturity date so that they may be publicly traded in the stock market. Examples include commodities, such as agricultural products (cattle, corn, wheat), and precious metals (gold, silver). Publicly traded refers to the fact that futures contracts can be used by speculators, rather than used as a hedge against inflation by actual buyers. Speculators are looking to make money on a favourable change in the foreign exchange rate, meaning the actual delivery of the commodity rarely ever occurs.

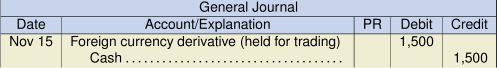

For example, on November 15, instead of a forwards contract, Monnard Inc. bought a futures contract for $1,500 that entitles the company to buy $100,000 USD at a cost of $108,000 CAD on February 15. In this case, $1,500 is paid to obtain the futures contract from the stock market. The entry would be:

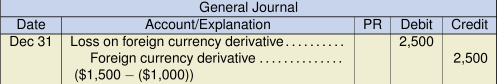

On December 31, company year-end, the exchange rate has changed, and $100,000 USD is worth only $102,000 CAD. This unfavourable drop means that the futures contract value will also drop. If the futures contract now has a negative value of ($1,000), a loss has occurred which Monnard Inc. must record as follows:

If the exchange rate had increased and $100,000 USD were now worth $111,000 CAD, a gain would be recorded as Monnard Inc.’s futures contract had fixed the price at $108,000 CAD. If the fair value of the futures contract increased to $2,000, Monnard Inc.’s entry to record the gain would be:

As can be seen from the two examples above, derivatives are measured at fair value with the gain or loss reported in net income. There are, however, two exceptions. The first relates to hedging and is beyond the scope of this textbook. The second is regarding derivatives that relate to a company’s own shares which are to be recorded at historic cost and not fair value. An example would be warrants attached to common shares and employee stock option plans, which will be discussed next.

One theoretically interesting area to look at is purchase commitments, where a company orders goods from a supplier, followed by receiving the goods in the future. There are similarities between a purchase commitment and derivatives, such as futures or forwards contracts. For example, a purchase commitment is drafted and signed in advance and is connected to underlying goods that have value. The commitment will be settled sometime in the future. So, why are purchase commitments not recognized as a derivative? The main reasons are because the intent of a purchase commitment is to obtain the goods and purchase commitments have no intrinsic value of their own, and therefore cannot trade in the marketplace. Also, purchase commitments are not settled by any means other than taking possession of the goods. Conversely, futures contracts can be publicly traded on their own, without ever taking possession of the underlying goods. For these reasons, purchase commitments are not considered to be derivatives and are recorded as a purchase of goods, once the risks and rewards of the goods have passed from the seller to the purchaser.