12.5 Provisions and Contingencies

IAS 37 deals specifically with provisions, contingent liabilities, and contingent assets. The standard defines a provision as a “liability of uncertain timing or amount” (CPA Canada, 2016, IAS 37.10). These uncertainties can create problems for accountants, as the questions of whether the item should be recorded, and what amount should be used if it is recorded, do not always have clear answers. In this section we will examine the general criteria to be used in evaluating provisions and contingencies, and we will look at two specific examples: product warranties and decommissioning costs.

The key feature of the definition of a provision is the existence of uncertainty. The standard distinguishes provisions from other current liabilities, such as trade payables and accruals, on the basis of this uncertainty. In comparison, there is no uncertainty regarding trade payables, as these are usually supported by an invoice with a due date. Even an accrual for a monthly utility expense does not contain sufficient uncertainty to be classified as a provision, as this amount can normally be estimated fairly accurately through examination of past utility bills. Although there is some uncertainty in this process of estimation, the uncertainty is far less than in the case of a provision. It is for this reason that IAS 37 requires separate disclosure of provisions, but not regular accruals.

The standard also defines a contingent liability as:

- a possible obligation that arises from past events and whose existence will be confirmed only by the occurrence or non-occurrence of one or more uncertain future events not wholly within the control of the entity; or

- a present obligation that arises from past events but is not recognized because:

- It is not probable that an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits will be required to settle the obligation; or

- The amount of the obligation cannot be measured with sufficient reliability. (CPA Canada, 2016, IAS 37.10).

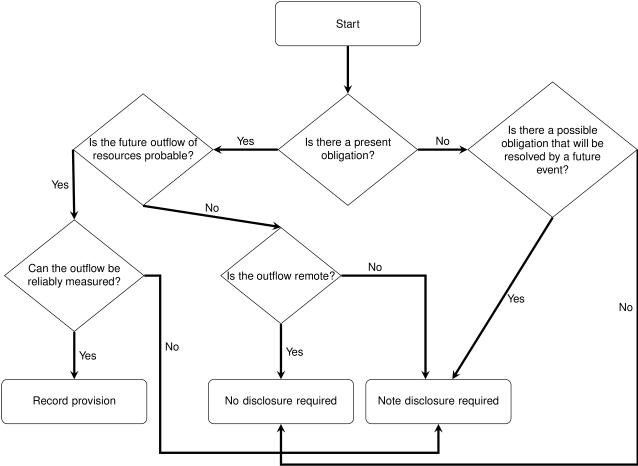

A careful reading of this definition will lead us to the conclusion that a contingent liability does not meet the general definition of a liability. The obligation may not be present due to the uncertainty of future events, or the uncertainty may make it impossible to determine if or how many economic resources will be outflowing in the future. For these reasons, the standard does not allow contingent liabilities to be recognized. A common example of a contingent liability would be a legal action taken against the company where the outcome cannot yet be predicted. The court’s decision to be rendered is the uncertain future event that is not within the entity’s control. However, in some cases, the company’s legal counsel may conclude that the decision is fairly certain based on the facts, in which case, recognition of a provision may be warranted. Significant judgment may be required in evaluating the correct accounting treatment of these situations. Contingent assets, which are also defined in relation to an uncertain future event, are also not recognized under the standard. However, there are disclosure requirements for contingent assets and liabilities, which will be discussed later. If an inflow of economic resources were virtually certain, however, then the asset would be recognized, as it is no longer considered contingent. The standard doesn’t define virtual certainty, but in practice it has come to mean a very high level of probability, usually greater than 95%.

In assessing whether an outflow of resources is probable, the standard defines this term as meaning that the event is more likely than not to occur. In mathematical terms, this would mean that the event has a greater than 50% probability of occurring. The standard also states that no disclosure is required if the probability of the outflow of resources is remote. This term is not defined in the standard. In practice, when making this determination most professional accountants will use a guideline of 5–10% maximum probability.

We can think of the guidance offered by IAS 37 in terms of a decision tree:

Product Warranties

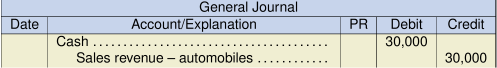

In Section 12.4, we looked at an example where the warranty contract was considered part of a bundled sale and the warranty revenue was recognized separately. In some cases, the warranty is not considered a separate performance obligation. In these cases, the warranty revenue would be recognized immediately as part of the total sale. However, this creates an accounting problem, as there are still potential future costs that will be incurred in servicing the warranty. In this situation, a provision needs to be established for those future warranty costs. This provision will help by reporting the expense in the same period as the related revenue. Let’s return to our example of Calvino Cars, but this time we will assume that the warranty does not represent a separate performance obligation. As before, the company estimates that 25% of the warranty repair costs will be incurred in the first year, and 75% in the second year. As well, based on prior experience with this car model, the company has estimated that the total cost of repairs for the warranty term will be $1,100. The journal entries that would be recorded at the time of sale would be:

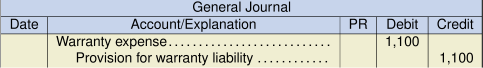

In the first year, repair costs of $304 are actually incurred for this vehicle. The journal entry required in this case is:

At the end of the first year, the company will report a current liability of $796 ![]() , which represents the unused portion of the warranty provision. If the warranty period extended beyond the end of the next operating cycle, then the provision would need to be separated into current and long-term portions. As it is possible that the actual warranty costs will not be the same as the predicted costs, an additional adjustment to profit or loss will be required when the warranty term expires in order to reduce the provision to zero.

, which represents the unused portion of the warranty provision. If the warranty period extended beyond the end of the next operating cycle, then the provision would need to be separated into current and long-term portions. As it is possible that the actual warranty costs will not be the same as the predicted costs, an additional adjustment to profit or loss will be required when the warranty term expires in order to reduce the provision to zero.

One question the accountant will need to face is how to estimate the future warranty costs. IAS 37 suggests that the obligation should be reported at the value that the entity would rationally pay to settle it at the end of the reporting period. This requires some judgment; however, the standard does supply some guidance on how to estimate this amount. When the population being estimated contains a large number of items, such as a warranty plan, the accountant should use the expected value method to determine the amount. This method looks at all the possible outcomes and applies a probability weighting to each. For example, if Calvino Cars were to determine the warranty obligation for all of the cars it sells, it may use the following calculation. If all of the cars sold were to contain minor defects, then the total cost to repair these defects would be $8,000,000. If all of the cars sold were to contain major defects, then the total repair costs would be $30,000,000. Based on experience and engineering studies, the company has determined that 80% of the cars it sells will have no defects, 17% will have minor defects, and 3% will have major defects. The warranty provision would then be calculated as follows:

![]()

The standard also suggests that when estimating a provision for a single item, the most likely outcome should be used. However, if the range of possible outcomes is not evenly distributed, it may be appropriate to accrue a provision that takes this skewed distribution into account. In making these judgments, the accountant will need to be aware that the subjective nature of these estimates may lead to earnings management or other attempts to manipulate the result. As always, the integrity of the reported amounts depends on the accountant’s skillful and professional application of the standard.

Decommissioning Costs

In the Property, Plant, and Equipment chapter, we briefly discussed the accounting treatment of decommissioning and site restoration costs. The general approach is to capitalize these costs as part of the asset’s carrying value and report an obligation, sometimes referred to as an asset retirement obligation. This obligation represents a provision and is covered by IAS 37.

The requirement to clean up and restore an industrial site often results from regulation. In order to obtain permission to operate a business that alters the natural condition of an area, a government authority may include restrictions in the operating license that require the restoration of the site, once the industrial activity is concluded. Common examples include: mineral extraction operations, oilfield drilling, nuclear power plants, gas stations, and any other businesses that might result in contamination of water or soil. In addition to the regulatory requirement, IAS 37 also considers the constructive obligation that may exist as a result of the company’s own actions. If a company has a publicly stated policy or past practice of restoring industrial sites to a condition beyond the requirements of legislation, then the company is creating an expectation of similar future performance. As a result, the amount of the obligation will need to include the costs required to meet the constructive, as well as the legal, obligations.

Let’s look at an example. Icarus Aviation Ltd. has just purchased a small, existing airport that provides local commuter flights to downtown businesses in Edwardston. Although the airport is already 50 years old, the company believes that it can still operate profitably for another 20 years until it is replaced by a newer airport, at which time the land will be sold for residential development. To obtain the operating license from the local government, the company had to agree to decontaminate the site before selling it. It is expected that this process will cost $10,000,000 in 20 years’ time as the site is heavily polluted with aviation fuel, de-icing solutions, and other chemicals. Also, the company has publicly stated that, when the airport is sold, part of the land will be converted into a public park and returned to the city. It is estimated that the park will cost an additional $2,000,000. As the company has both legal and constructive obligations, the total site restoration costs of $12,000,000 need to be recorded as an obligation. Because the costs are to be incurred in the future, the obligation should be reported at its present value. IAS 37 requires the use of a discount rate that reflects current market conditions and the risks specific to the liability. If we assume a 10% discount rate in this case, the present value of the $12,000,000 obligation is $1,783,724.

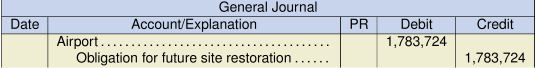

At the time of the acquisition of the property, the following journal entry is required:

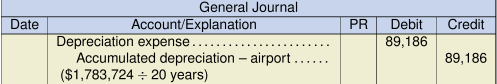

As the site restoration cost is included in the property, plant, and equipment balance, it needs to be depreciated each year. Assuming straight-line depreciation, the following journal entry would be required each year:

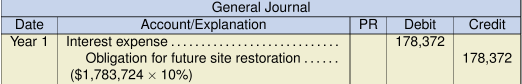

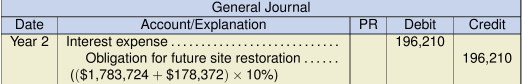

Additionally, interest on the obligation needs to be recorded. This will be calculated based on the carrying amount of the obligation each year. For the first two years, the journal entries will be:

The interest expense will increase each year as the obligation increases. At the end of 20 years, the balance in the obligation account will be $12,000,000. Over the 20-year period, the total amount expensed (interest plus depreciation) will also equal $12,000,000. Thus, the cost of the site restoration will have been matched to the accounting periods in which the asset was used.