12.3 Current Financial Liabilities

Trade Accounts Payable

Trade accounts payable are likely the most common current liability presented in company financial statements. The balance results from the purchase of goods and services from suppliers and other entities on account. A typical business arrangement would first involve the supplier approving the purchasing company for credit. Once this is done, the purchasing company would be allowed to purchase goods or services up to a maximum amount, with payment required within some specified period of time. Typical terms would require payment within 30 to 60 days from the date of purchase. Many suppliers will also encourage early payment by offering a discount if payment is received within a shorter time period, often as little as 10 days. These types of arrangements were previously discussed in the cash and receivables chapter. From the perspective of the purchaser, the amount of any discount earned by early payment should be deducted directly from the cost of the inventory purchased or any other asset/expense account debited in the transaction.

One issue that accountants need to be concerned with is ensuring that accounts payable are recorded in the correct accounting period. A basic principle of accrual accounting is that expenses should be recorded in the period in which the goods or services are consumed or received. This means that the liability for those purchases must also be recorded in the same period. For this reason, accountants will be very careful during the period immediately before and after a reporting date to ensure that the cut off of purchase transactions has been properly completed. The issue of goods-in-transit at the reporting date was previously discussed in detail in the inventory chapter.

Lines of Credit

Management of operating cash flows is an essential task that must be executed efficiently and effectively in all companies. The nature of the company’s operating cycle will determine how long the company needs to finance its operations, as cash from sales will not be immediately collected. Many companies will negotiate an agreement with their banks that allows them to borrow funds on a short-term basis to finance operations. A line of credit essentially operates as a regular bank account, but with a negative balance. A company will make disbursements of cash through the line of credit to purchase goods, pay employees, and so on, and when money is received from customers, it will be used to pay down the balance of the line of credit. At the end of any particular reporting period, the company’s bank balance may be positive, in which case it would be reported in the current asset section as cash. If it is negative, for example if the line of credit has been drawn upon, it would be reported as bank indebtedness in the current liability section.

The line of credit will be governed by a contract with the bank that specifies fees and interest charged, collateral pledged, reporting requirements, and certain other covenant conditions that must be maintained (such as maintenance of certain financial ratios). Because of these contractual conditions, there are a number of disclosure requirements under IFRS for these types of bank indebtedness. These will be discussed later in the chapter.

Note as well that another lender related current financial liability is the current portion of long-term debt. This represents the principal portion of a long-term liability that will be paid in the next reporting period, and will be covered in more detail in the long-term financial liabilities chapter.

Notes Payable

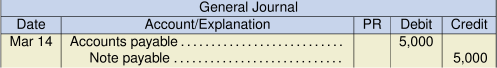

In the cash and receivables chapter, we discussed the accounting entries and calculations for short-term notes receivable. In the case of notes payable, the journal entries are a mirror of those, as we are simply taking the perspective of the other party in the transaction. In the example used in the cash and receivables chapter, the note was issued in exchange for the cancellation of an outstanding trade payable. As well, notes may sometimes be issued directly for loans received.

If we revisit the Ripple Stream Co. example from the cash and receivables chapter, the journal entries required by the debtor would be as follows:

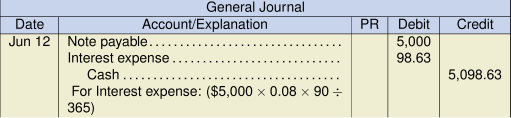

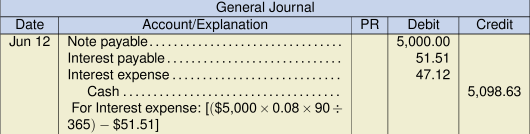

The entry for payment of the note 90 days at maturity on June 12 would be:

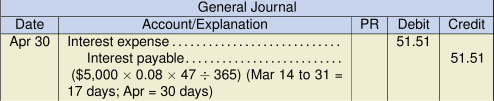

If financial statements are prepared during the period of time that the note payable is outstanding, then interest will be accrued to the reporting date of the balance sheet. For example, if the company’s year-end was April 30, then the entry to accrue interest from March 14 to April 30 would be:

When the cash payment occurs at maturity on June 12, the entry would be:

IFRS requires the use of the effective interest method for the amortization of zero interest notes and other financial instruments classified as loans and receivables. Thus, the journal entries from the perspective of the debtor for these different types of notes will simply be the reverse of those presented in the Cash and Receivables chapter. They will follow a similar pattern, as outlined above.

Customer Deposits

Businesses may sometimes require customers to pay deposits in advance of the delivery of the service or good for which it is contracted. These deposits serve a variety of purposes. A common example is a landlord requiring a security deposit that will be refundable at the end of the lease, if there is no damage to the property. If the property is damaged, then the deposit will be retained to cover the cost of repairs. Another type of deposit may be required for special order or custom designed goods. As the vendor may not be able to fully recover its costs on such contracts if the customer were to cancel, the deposit is required to ensure the commitment of the customer. As well, utility companies will often require deposits from customers to cover the cost of any unpaid balances that may arise if the customer were to move out of premises prior to receiving the final invoice.

Although the circumstances that create these deposits may be different, the accounting treatment still follows the same basic rules for classification described in Section 12.2. If the company expects the liability to be settled within the operating cycle, or if the company has no unconditional right to defer settlement beyond 12 months, then the liability would be classified as current. If these conditions are not true, then the liability would be classified as non-current. The individual conditions of the contract would need to be examined to determine the proper classification.

Sales Tax Payable

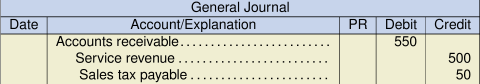

Many countries and tax jurisdictions levy sales taxes on the sale of certain products and services. These types of taxes are often referred to as value-added taxes (VAT) or goods and services taxes (GST). Although the tax rules in each jurisdiction will vary, the general approach to these types of taxes will be similar in any location. A sales tax collected by an entity on the sale of goods or services represents a liability, as the tax is being collected on behalf of the relevant government authority. To use a simple example, assume a company sells $500 of professional services to a customer in a jurisdiction that requires a sales tax of 10% be charged. The journal entry would look like this:

When the sales tax is remitted to the government authority, the sales tax payable account would be reduced accordingly. These liabilities will usually be classified as current, as the relevant government authority would normally require payment within a fairly short time period (usually monthly or quarterly).

When we look at this transaction above, we should also consider the accounting for the purchaser of the service. The treatment of the tax paid will depend on the rules in the relevant jurisdiction. If the sales tax is refundable, the payer can claim a credit for the amount paid. If the sales tax is non-refundable, then the payer simply absorbs this cost into the operations of the business.

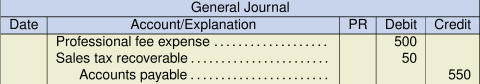

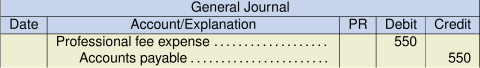

Using the example above, the journal entries for the purchaser would be as follows:

Refundable Sales Tax Jurisdiction

Non-Refundable Sales Tax Jurisdiction

When the sales tax is non-refundable, it simply gets included in the relevant expense account. If the purchase were related to an inventory or a property, plant, and equipment item, then the tax would be included in the initial cost of acquisition for the asset. In some jurisdictions, it is possible that both refundable and non-refundable sales taxes will apply to a particular purchase. In those cases, the two tax amounts will need to be separated and treated accordingly.

The form to complete to either request a refund or submit a payment for a province that has HST, is shown below:

HST-GST Return Working Copy Form (PDF)

Employee Payables

There are a number of current liabilities reported with respect to the employees of the business. Some of these liabilities will be discussed below.

Salaries and Wages Payable

Any amounts owing to employees for work performed up to the end of the accounting period need to be accrued and reported. For employees who are paid an hourly wage, the amount is simply determined by multiplying the hourly rate by the number of hours worked since the last pay date, up to the reporting date. For salaried employees, the calculation is usually performed by determining a daily or weekly rate and then applying that rate to the appropriate number of days. Consider the following example: an employee receives an annual salary of $60,000 and is paid every two weeks. The last pay period ended on May 26, and the company reports on a May 31 year-end. The amount of salary to accrue would be calculated as follows:

| Annual salary | $60,000 |

| Bi-weekly salary (÷26 weeks) | $2,307.69 |

| Amount accrued, May 27-31 (5 days) | $1,153.85 |

Note that when an employee is paid a bi-weekly salary, it is normally presumed that the work week is 5 days and that the pay period is 10 days (i.e., 2 work weeks). Thus, we accrue one-half of the regular bi-weekly pay in this example. The accrued amount would be reversed in the following accounting period when the next salary payment is made.

Payroll Deductions

Payroll deductions, also referred to as source deductions, are a common feature in most jurisdictions. Government authorities will often levy income taxes on employment income and will require the employer to deduct the required amount directly from the employee’s pay. Thus, the amount is deducted at the source. The amount deducted by the employer represents a type of trust arrangement, as the employer is agreeing to submit the funds to the government on behalf of the employee. As these deductions are required to be submitted in a timely manner to the relevant government authority, they are reported as current liabilities. Additionally, aside from income taxes, government authorities may require other deductions. In Canada, for example, most employees must also pay Canada Pension Plan and Employment Insurance premiums. For these types of deductions, the employer must submit a further amount, based on a proportion of the amount the employee pays. Thus, the company will report a liability greater than the amount deducted from the employee, with the difference, the employer’s share, representing an expense for the company.

There are other types of deductions taken from employee’s pay that are not the result of a government levy. Examples include these instances: employers may provide private pension plans that require monthly contributions, employees may belong to unions that require dues payments based on the level of earnings, employees may have extended health benefits that require payment, or employees may have to pay a monthly fee for parking. There are numerous examples of employee deductions, and the accounting treatment of these items will depend on their natures. If the item is deducted in trust for another party, then the company must report it as a liability. If the amount is not submitted to a third party, then the employer may report it as either a cost recovery or a revenue item. Calculations of various types of source deductions can become fairly complex and, as a result, most companies will employ staff with specialized training to take care of the accounting for payroll matters.

Paid Absences

Many employers allow their employees time off from work with pay. IAS 19 describes these kinds of arrangements as paid absences and classifies them into two types: accumulating and non-accumulating.

Accumulating paid absences are those that can be carried forward into a future accounting period if they are not fully used in the current period. An annual vacation entitlement is a common example of this type of paid absence. Employment law in many jurisdictions requires employers to give a certain amount of time off with pay each year to its employees. Employers may choose to grant more than the legally required minimum vacation time as a way to attract and retain high-quality employees. Because the employees earn the paid vacation time based on the time they work, an obligation and expense is created, even if the employees haven’t taken the vacation. IAS 19 further distinguishes accumulating paid absences as being either vesting or non-vesting. Vesting benefits are those for which the employee is entitled to a payment upon termination of employment, while non-vesting benefits are those for which no such entitlement exists. In the case of paid vacation, the minimum legally required vacation time would be considered a vesting benefit, while any additional vacation granted by the employer may or may not be considered vesting, depending on the terms of the employment contract. IAS 19 requires that a liability be established for both vesting and non-vesting accumulating benefits. This means that the entity needs to make an estimate of the additional amount that needs to be paid at the end of the reporting period for the unused entitlement to accumulating paid absences. For those paid absences that are non-vesting, the entity would need to estimate the amount that won’t be paid out due to employee termination. This could be done by examining past employee turnover patterns or other relevant data.

Consider the following example. Norstar Industries employs 100 people who are each paid $1,000 per week. By December 31, 2020, each employee has earned two weeks of vacation that are considered vesting and a further week of vacation that is considered non-vesting. Note that no vacation was taken by the employees during 2020. Based on past history, the company estimates that 5% of its employees will leave before taking their vacation, thus losing their entitlement to the non-vesting portion. As well, the company has budgeted for a 3% salary increase to take effect on January 1, 2021. The liability for vacation pay would be calculated as follows:

| Vesting benefit: | 100 employees × $1,030 per week × 2 weeks | = $206,000 |

| Non-vesting benefit: | 95 employees × $1,030 per week × 1 week | = $97,850 |

| Total obligation | = $303,850 |

Note that the calculation is based on the pay rate that is expected to be in effect when the employees take their vacation. The total obligation would be reported as a current liability and an expense on the December 31, 2020 financial statements. In 2021, as the employees take their vacation, the liability would be reduced. If the estimates of employee terminations or salary increases were incorrect, then the expense in 2021 would be adjusted to reflect the actual result. No adjustment to the previous year’s accrual would be made.

Non-accumulating paid absences refer to those entitlements that are lost if they are not used. Sick days often fall into this category. Employees may be allowed a certain number of sick days per month or year, but these do not accumulate beyond the end of the relevant period. Additionally, employees are not entitled to a cash payment for unused amounts if their employment is terminated. Other common examples of non-accumulating paid absences include the following: parental leave (maternity, paternity, or adoption), leave for public service (e.g., jury duty), and some short-term disability leaves. In these cases, the company does not accrue any expense or liability until the absence actually occurs. This makes sense as it is not the employee’s service that creates the obligation, but rather the event itself.

Profit-Sharing and Bonus Plans

In addition to regular salary payments, companies often establish bonus plans for their employees. These plans may be made available to all employees, or there may be different schemes for different groups. The purpose of a bonus plan is to motivate employees to work toward the best interests of the company and of its shareholders. Bonus plans and profit-sharing arrangements are, therefore, intended to act as a method to relieve the agency theory problem that was discussed in the review chapter.

Bonuses will usually be based on some measurable target and often rely on accounting information for their calculation. A common example would be to pay out employee bonuses as a certain percentage of reported profit. The individual employee’s entitlement to a bonus will be based on some measurable performance objective that should be determined and communicated at the start of the year. As bonuses are really just another form of employee remuneration, IAS 19 requires them to be accrued and expensed in the year of the employee’s service, assuming they can be reasonably estimated. IAS 19 also notes that bonuses may result from both legal and constructive obligations. Thus, even though the company’s employment contracts may not specify a bonus calculation, consistent past practices of paying bonuses may create a constructive obligation. The calculation used in the past would then form the basis for the current accrual. IAS 19 also requires accrual of the amount expected to be paid out for the bonuses. That is, if a bonus payment is only paid to employees who are still employed at the end of the year, the calculation of the accrued bonus will need to consider the number of employees who leave before the end of the year.

Consider the following example. A company with 25 employees has historically paid out a bonus each year of 5% of the pre-tax profit. The current year’s pre-tax profit is $1,000,000. The bonus will be paid out two months after the year-end, but employees will only receive the bonus if they are still employed at that time. In prior years, the company has experienced, on average, the departure of two employees between the year-end and the bonus payment. Bonuses not paid to departed employees are retained by the company and not redistributed to the other employees. The amount to be accrued at year-end would be calculated as follows:

| Total bonus: | $1,000,000 × 5% | = $50,000 |

| Bonus per employee: | $50,000 ÷ 25 | = $2,000 |

| Actual bonus expected to be paid: | $2,000 × 23 employees | = $46,000 |

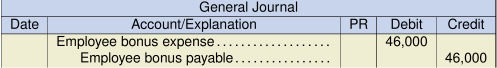

The company would then make the following journal entry at its year-end: