Module 2: Gender and Sexuality

Trans

A Note on Language

This lecture uses the term trans to describe the experience of gender diverse individuals during a time where certain frames were unavailable to describe their experience. Rather than perpetuate a narrative absent of and ultimately conflicting with gender diversity, scholars have responded to the limitations of the present-day term transgender, and innovated a method of analysis beyond binary identity categories. In their work, “Trans-, Trans, or Transgender?” trans scholars Susan Stryker, Paisley Currah and Lisa Jean Moore coined the use of the prefix trans, “which remains open-ended and resists premature foreclosure by attachment to any single suffix,” and its subsequent verbing, transing.3 Transing analysis is born of the sentiment that:

[…] neither ‘-gender” nor any of the other suffixes of ‘trans-’ can be understood in isolation […] the lines implied by the very concept of ‘trans-’ are moving targets, simultaneously composed of multiple determinants. ‘Transing,’ in short, is a practice that takes place within, as well as across or between, gendered spaces. It is a practice that assembles gender into contingent structures of association with other attributes of bodily being, and that allows for their reassembly.4

In this case, trans is reconceptualized from stringent and defined to fluid and all-encompassing, rejecting its dismissal on the ground of inapplicable specificity; transing becomes an avenue of diverse interrogation, identifying the power structures that produce and suppress normative and non-normative articulations of gender, race, ability and other modes of being in this history. The use of this term is a scholarly intervention that this project employs with careful consideration.

3 Susan Stryker, Paisley Currah, and Lisa Jean Moore, “Introduction: Trans-, Trans, or Transgender?” Women’s Studies Quarterly 36, no. 3/4 (2008): 11.

4 Susan Stryker, Paisley Currah, and Lisa Jean Moore, “Introduction: Trans-, Trans, or Transgender?” Women’s Studies Quarterly 36, no. 3/4 (2008): 13.

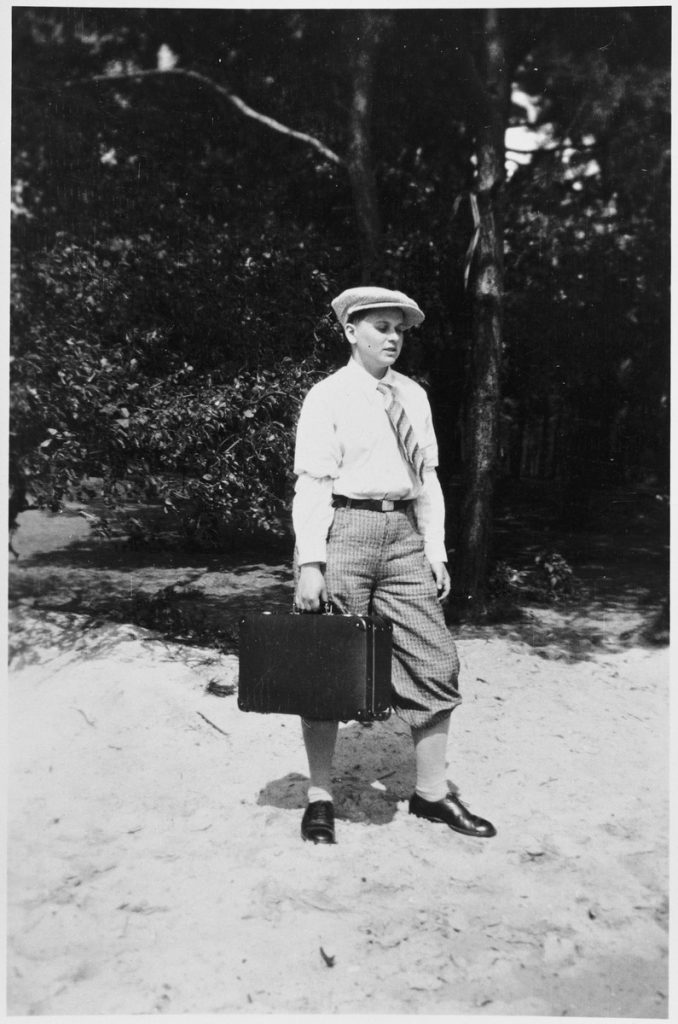

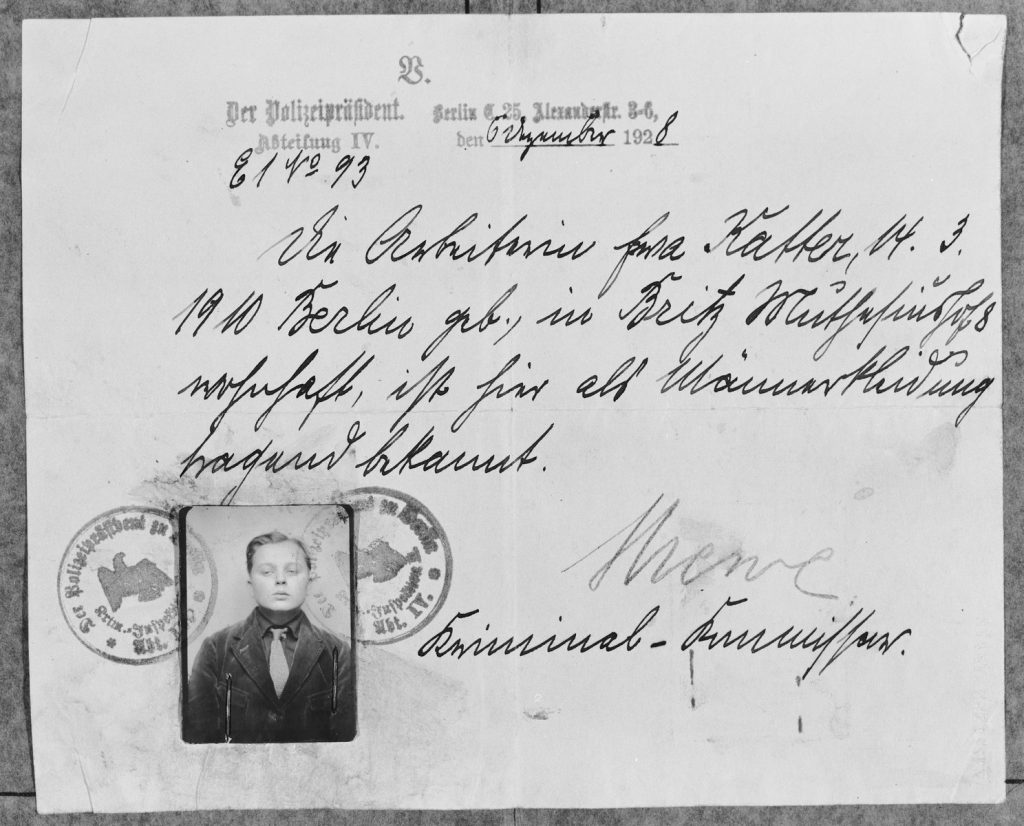

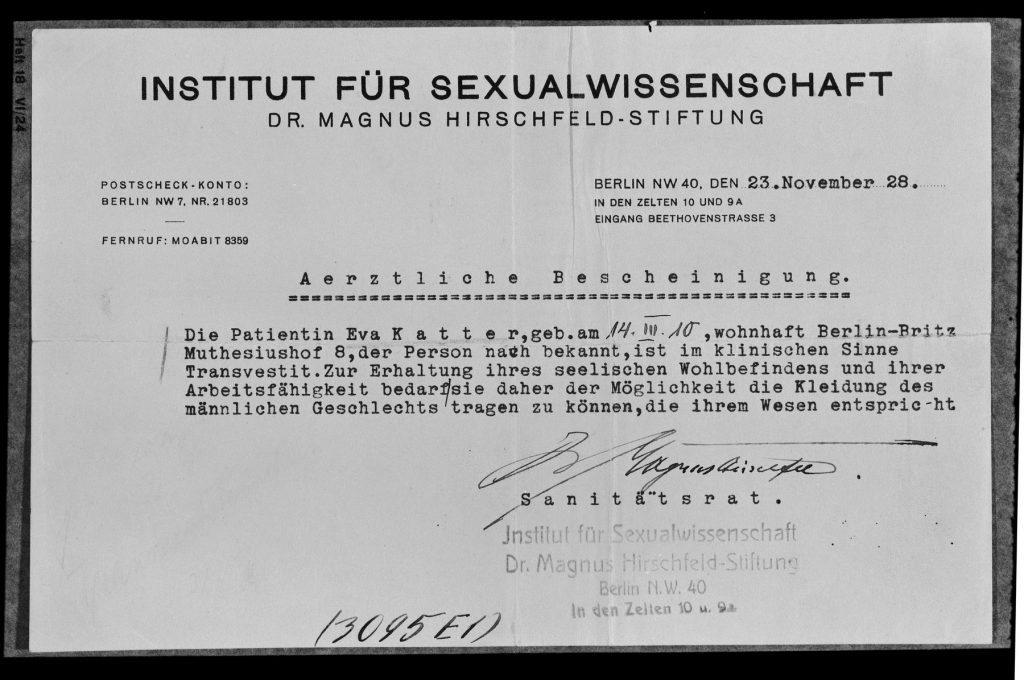

As described earlier in this submodule, Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science was on the forefront of research on trans individuals. Hirschfeld coined the term transsexualität, which would eventually be translated into transsexual, and performed gender affirming surgeries for many patients. Hirschfeld also worked with local police to reduce the harassment of gender diverse individuals on the street. One of the proposed remedies to persecution was the Transvestitenschein, an identification card that gave permission for the carrier to act and look the way they did, regardless of whether it aligned with their sex assigned at birth. Despite the seemingly progressive conditions for trans and gender diverse people in Weimar Berlin, these passes were still withheld from some, such as sex workers, exemplifying that not all trans people had the means or desire to acquire these documents. Under Nazi rule, records of trans existence became confined to police reports, life-writing and eyewitness testimony.

Jewish LGBTQ+ Individuals

This module has described the experiences of many LGBT+ individuals, and has foregrounded the stories of those who were also Jewish. As demonstrated by the stories of Magnus Hirschfeld, Gad Beck, Manfred Lewin, Henny Shermann, Annette Eick and Frieda Belinfante, those who carried both Jewish and LGBT+ identities were persecuted first and foremost as Jews. It is critical that we recognize the troubling dynamics presented by the persecution of these overlapping identities—how many LGBTQ+ Jewish lives were lost or went unrecognized? How did Nazi ideologies around race and sex converge uniquely to impact these individuals? In the foregrounding of Jewish LGBTQ+ testimonies, this submodule attempted to speak to this absence in the archives and to honour the stories of those individuals lost.