Module 2: Gender and Sexuality

Persecution

Guest Lecture by Dr. Geoffrey Giles

In this second guest lecture, Dr. Geoffrey Giles explains the connection between sexuality and Nazi ideology. Through this guest lecture, you will learn how Nazi ideologies shaped the experience of Jewish women, homosexuals, and so-called Aryans.

Chart of Prisoner Markings: A Representation

The Chart of Prisoner Markings was created by the digital artist Jessika Thiffault. Click on the red information icon to learn more about the uniform and the triangles used to categorize prisoners in concentration camps. Through those icons, you will also see the artefacts that inspired this drawing.

The Sewing of a Pink Triangle: A Representation

“The Sewing of a Pink Triangle” was created by the digital artist Jessika Thiffault. Click on the red information icon to learn more about the photograph and artefact that inspired this drawing. By exploring the icons on this image, you will also learn about Nazi propaganda images.

Pierre Seel

Pierre Seel, born in Alsace, France in 1923, was deported to the Schirmeck internment camp in 1941 at 18 years old for being gay. Pierre was the only French man to ever testify to being deported on the grounds of homosexuality and the work he has done to tell his story has been critical to the historical acknowledgement of those events. Pierre Seel’s testimony is critical to understanding the treatment of gay men in concentration camps; he speaks explicitly and emotionally about experiences of violence and sexual assault that were previously unknown. In his later years, Pierre was engaged in an intense legal battle for recognition as a political deportee by the French government. Though homosexual deportees were hypothetically recognized, the qualifying criteria for Pierre to gain recognition and receive reparations was brutally unreasonable, requiring eyewitness testimony from men who were long dead. While Pierre Seel was eventually awarded his status as a deportee, it is not believed that he ever received restitution or compensation from the German or French government.

In the following passage from I, Pierre Seel, Deported Homosexual, Pierre Seel describes the death of his friend, Jo, a gay man, at eighteen years old in Schirmeck internment camp.

Heinz Dormer, Paragraph 175 (2000)

Heinz describes how gay men and Jews were tortured differently in the concentration camp at which he was imprisoned. Epstein, Rob et al. Paragraph 175. San Francisco, California, USA: Kanopy Streaming, 2000. Film.

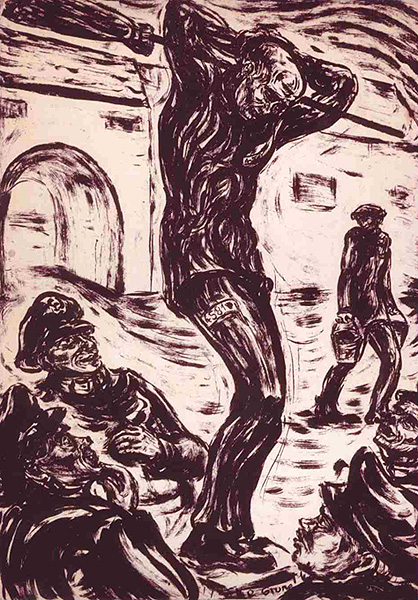

Born in 1903, Richard Grune was an artist who completed courses at the Bauhaus School in Weimar. Having moved to Berlin in 1933, Grune was arrested in 1934 after being denounced as a homosexual. Upon identifying himself as such, Grune was transferred and imprisoned in Neumünster Prison for violating Paragraph 175. He was reimprisoned in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1937, and then transferred to Flossenbürg where he remained until the end of the war. While at Flossenbürg, Grune was forced to work in the Künstlerkommando or “Artists’ Commando,” an assignment which may have saved his life. After the war, Grune produced a series of lithographs that document the experiences of himself and others in the camps. In 1948, Grune was reimprisoned under Paragraph 175 once more. The Flossenbürg Memorial speaks to Grune’s experience, stating that “[t]he refusal to recognize him as a victim of National Socialist violent crimes and the renewed persecution had a profound effect on him,” up until his death in 1984. His woodcuts are considered an invaluable testimony to the realities of these concentration camps—perhaps some of the most important documentation produced in the immediate post-war period.

Reflection Questions:

- Why is sexuality so key to Nazi ideology?

- How were Jews and gay men treated differently in the camp systems? How were they treated in similar ways?