Module 2: Gender and Sexuality

The Muselmänn

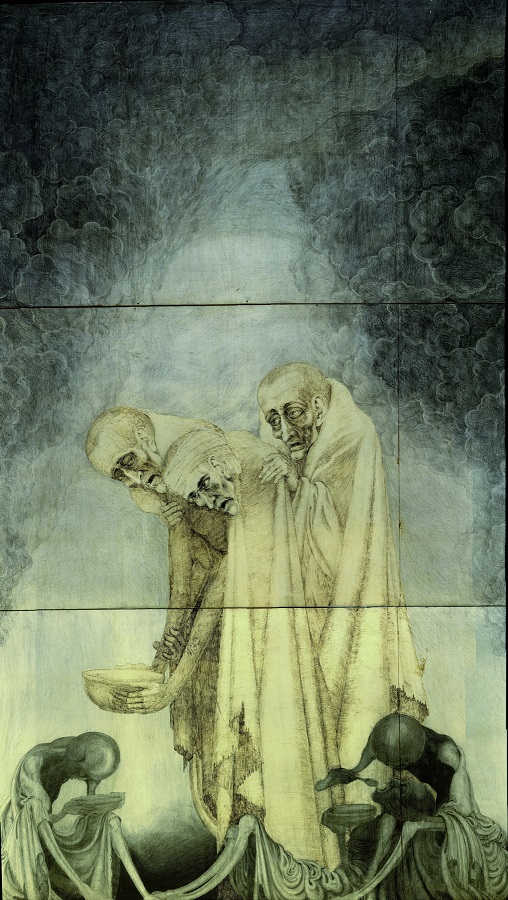

This painting by Polish Catholic artist Marian Kolodziel is an artistic representation of the Muselmänn being supported by two other inmates while two others sit below, focused on eating their rations. The care of the Muselmänn is at odds with accounts that describe how inmates often shunned the Muselmänn as they struggled for their own survival and feared descending into despair themselves. Kolodziel was imprisoned at Auschwitz for 5 years. Kolodziel only spoke of his experiences in 1993 after a severe stroke prompted him to take up pen-and-ink drawings as part of his rehabilitation. He is most well-known for his drawing and art installation, The Labyrinth, which is housed in a church near Auschwitz and which is documented in the documentary film.

‘This is not an exhibition, nor art. These are not pictures. These are words locked in drawings…I propose a journey by way of this labyrinth marked by the experience of the fabric of death…It is a rendering of honor to all those who have vanished in ashes.’ -Marian Kolodziej

Kolodziej, Marian . ‘About Marian Kołodziej,’ The Labyrinth Documentary.

Muselmänner

Reflection Questions:

- What is the meaning of hygiene in Primo Levi’s account?

- Primo Levi asks us to be transformed by reflecting on the Holocaust. How should Holocaust narratives (including oral histories) transform us?

Artistic Representations and the Holocaust

How should we think about artistic representations of the Holocaust? German philosopher Theodor Adorno famously stated that ”to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. And this corrodes even the knowledge of why it has become impossible to write poetry today.” (“Culture Critique and Society,” originally written in 1949, in Prisms, 1955, pp. 34). What did he mean? He is often misquoted as saying art was “impossible” after the Holocaust. Is it? Throughout this project, we have pointed you towards artistic representations as responses to the Holocaust, most often by survivors. Adorno was concerned with cultural criticism. How can we think about German culture, the culture that produced the Holocaust, after the Holocaust? By extension, how do we struggle with all culture after the Holocaust? Adorno clarified his position after being much misunderstood and misquoted that “perennial suffering has as much right to expression as the tortured have to scream.” (From Part III, “Meditations on Metaphysics,” in Negative Dialectic). Poetry, or any art, is barbaric after the Holocaust when it is a facile commodification of suffering. In fact, Adorno’s dictum demands that we radically and critically engage this history through art and culture.