Module 2: Gender and Sexuality

Missing Voices

Missing Voices

In this clip, Dr. Klaus Mueller describes the importance of research and its capacity to change reality and to recover history. This is contextualized by Dr. Mueller’s experience interviewing Frieda Belinfante, a Jewish lesbian resistance fighter whose story is included in this lecture. Frieda is an example of a missing voice recovered. To continue recovering the stories of those lost—the stories of gay men, lesbians, trans people, and Jewish LGBTQ+ people and others obscured by time and circumstance—Dr. Mueller turns to a new generation to continue to do the work of re-reading research, reading the documents of the perpetrators against the grain, and, even when we are left only with traces, employing our imaginations to save a story from oblivion and honor LGBT victims and survivors as the unique individuals they were.

Himmler’s infamous quote regarding homosexuality, “those who practice homosexuality deprive Germany of the children they owe her,” was twofold; if women were sexually unavailable to men, then more men would be driven to homosexuality. In this way, lesbians became a threat to the nation; however, unlike gay men, lesbians were not persecuted explicitly under Paragraph 175. The Nazis viewed women’s sexuality as dominatable; by their logic, lesbian women could be forced to change, and if they didn’t, they could be sent to camps under the title of ‘asocial’ or ‘political prisoner.’ This course of persecution towards lesbians leaves us with an unclear record of experiences. The following are some examples of the testimonies that exist.

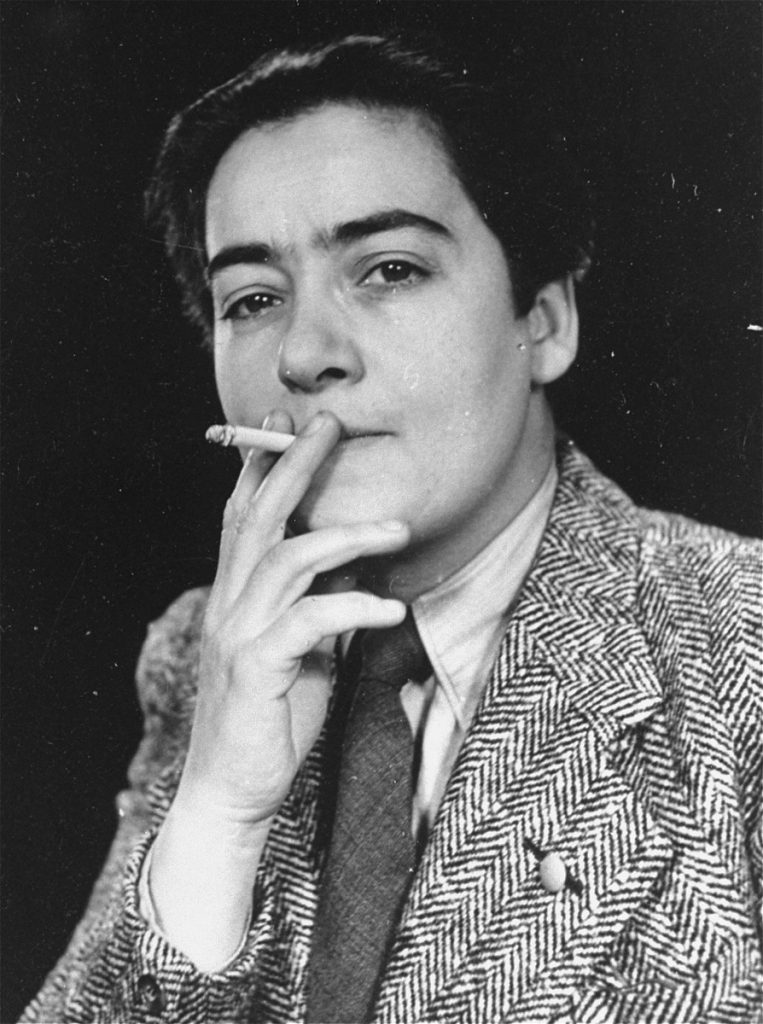

Frieda Belinfante

Frieda Belinfante, born in Amsterdam in 1904 to a Jewish father and a gentile mother, was a prominent Dutch conductor and member of the Dutch resistance. Belinfante was the first female artistic director and conductor of a major orchestra in Europe; she was also a Jew and a lesbian. Belinfante played a major role in the Dutch resistance, forging papers for people and suggesting and taking part in the bombing of the Amsterdam registry in 1943. The destruction of the registry was crucial; without it, the Nazis had nothing to compare falsified documents to. After the events of the bombing, Frieda hid, living as a man, and eventually fled to Switzerland. Belinfante’s testimony speaks to the harsh actions taken at the borders; she describes how she was only permitted to remain after revealing that she was a woman, and after her former teacher, the famous Jewish conductor Hermann Scherchen, vouched for her identity. Frieda’s travel companion, a man named Toni van Praagh, was thrown back across the Swiss border and eventually killed in Auschwitz. Frieda’s story is important for its uniqueness. Her experience exemplifies what it was like for a masculine woman in the Netherlands, socially and professionally, and she provides insight as to what it was like for women in the resistance: that is, how roles were delegated and to whom. Like Gad Beck’s testimony, Frieda Belinfante’s story also speaks to the tension between multiple persecuted identities at this time, as she was persecuted first as a Jew rather than a lesbian.

Oral history Frieda Belinfante

Frieda Belinfante describes her participation in the Dutch resistance’s bombing of the Amsterdam population registry in 1943. Learn about another example of the Dutch resistance in our interview with Susan Bloomfield.

Annette Eick

Annette Eick, born in Berlin in 1909, was a Jewish lesbian poet. In an interview with Claudia Schoppmann, Eick recalled how she utilized her connections to lesbian social circles in Berlin to obtain immigration papers and avoid persecution by the Nazis. “I already had the desire to be with women,” she recalled. “In this club I got to know a woman, Ditt, who looked a bit like Marlene Dietrich whom I liked as a type even if she was a bit vulgar.” After surviving an attack during Kristallnacht in 1938, Eick received papers disguised as a love letter from Ditt, and these papers allowed for her escape to London in the United Kingdom. Eick’s parents were killed at Auschwitz. Eick remained in the UK for the rest of her life with her partner, Gertrude Klingel (1901-1989), until her passing in 2010 at the age of 100.

Annette Eick (born 1909) – Driven into exile by the Nazis

Recommended Readings

Reflection questions:

- What are the main factors that explain why we are still “missing voices” from the LGBTQ+ history of the Holocaust?

- Thinking about Nazi ideology and how sex and sexuality functions within that ideology, why were the Nazis less focused on lesbians than on male homosexuality?