Module 3: Religion & Culture

Saints and Controversies

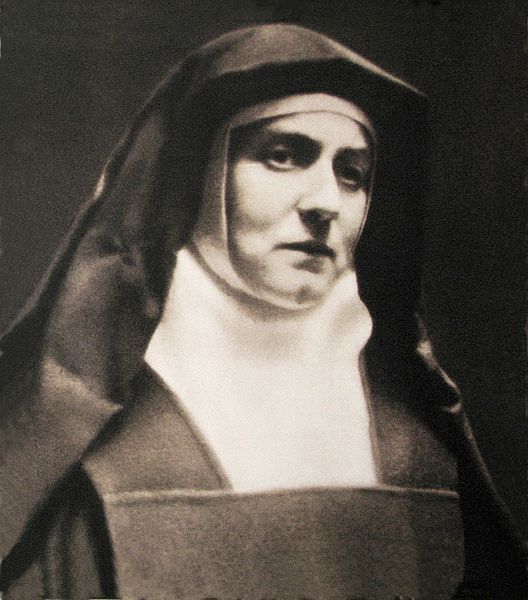

Edith Stein (1891–1942)

Edith Stein was a Jewish convert to Catholicism who became a Discalced Carmelite nun. She was sainted after being murdered in Auschwitz for being a Jew on August 7, 1942. She was a German philosopher, only the second woman to receive a degree in philosophy from a German university, who waged a legal battle to secure the right to teach as a faculty member when women were not permitted to do so, setting a precedent for other women in academia. Her interest in religious philosophy led to her conversion from Judaism to Catholicism in 1922. In 1933, Stein requested an audience with Pope Pius XI and when she was refused wrote to explain how serious the situation was on the ground and to underscore the anti-Christian features of National Socialism. She received no response.

Without an Aryan certificate, Stein lost her professorship when Jews were purged from the universities in April 1933. She entered the novitiate several months later and was ordained as a Carmelite nun in 1934 and took the religious name Teresa Benedicta of the Cross.

Teresa was transferred for her own safety from Cologne to Echt, Holland when Christians of Jewish descent began to be increasingly targeted by the Nazis. When the Dutch Bishops condemned Nazi antisemitism and the deportations of the Jews in a pastoral letter written in July of 1942, the German authorities retaliated by arresting baptized Roman Catholics of Jewish descent including Teresa and her sister, who was also a convert. Both Teresa and her sister were sent to Auschwitz and were murdered two days later on August 9, 1942.

In one of his most contentious canonizations, Pope John Paul II beatified Edith Stein, canonizing her in 1998. The choice to do so has provoked criticism from those who view the choice as evidence of the Catholic Church’s persistent Christocentric framing of the Holocaust. From Jewish perspectives, Edith Stein was one of the six million Jews murdered by the Nazis because she was Jewish. To claim her as a Catholic saint, and specifically as a Christian martyr, denies that truth. More subtly, but just as importantly, the fact that Stein was a convert and is celebrated in this way suggests an uncritical approach to the Church’s traditional mission to convert Jews and the ways in which that mission has historically been entangled with anti-Judaism in the history of Christian persecution of the Jews.

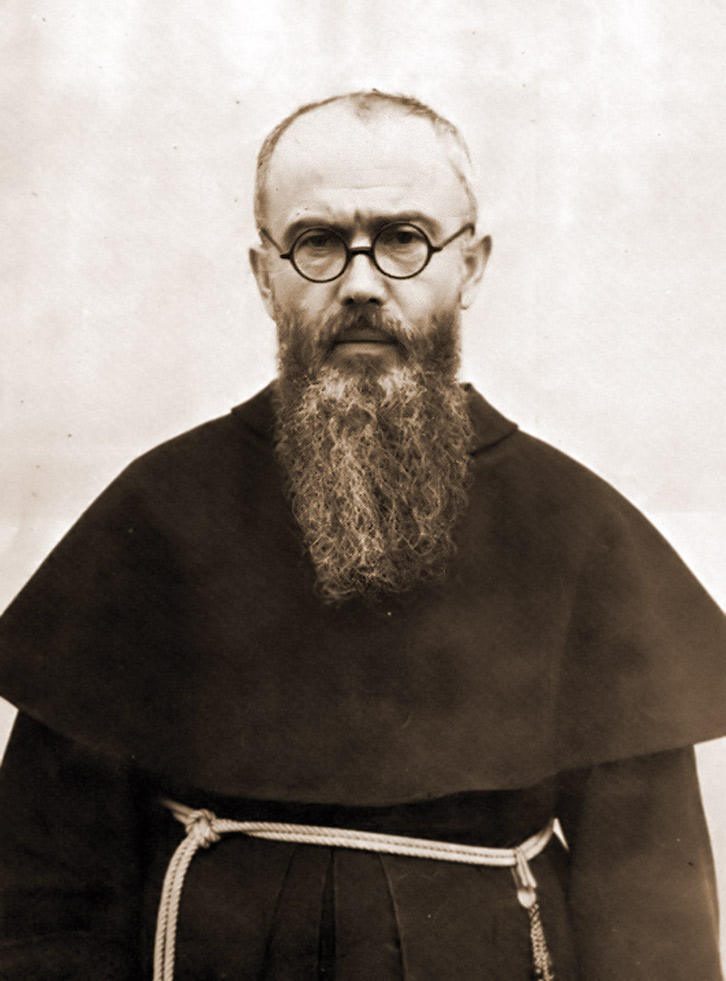

Maximilian Marie Kolbe

Stein was one of two murdered victims from Auschwitz who were canonized as saints by the Roman Catholic Church. The other, Maximilian Marie Kolbe, was born a Catholic.

Kolbe was a Polish Catholic priest and Conventual Franciscan friar serving in a monastery in Poland when the war broke out. When the Germans captured the area, Kolbe was arrested in September 1939, and then released in December. Despite the protection it would provide him, Kolbe refused to sign the Deusche Volkiste (which would have attested to his German ethnic ancestry and given him rights in line with those of German citizens). He returned to his monastery where he and his fellow friars sheltered Polish refugees, including 2,000 Jews, at the Niepokalanów friary. He was arrested by the Gestapo when his monastery was closed by the local German authorities.

Kolbe volunteered to take the place of Roman Catholic Polish prisoner Franciszek Gajowniczek.

Gajowniczek had been selected to starve to death in reprisal for another prisoner escaping from their barracks. When he cried out, “My wife! My children!” Kolbe asked to take his place. After two or three weeks of starvation with no food or water, Kolbe survived. He was murdered by prison guards who administered a lethal injection of carbolic acid. He died on August 14, 1941.

Pope John Paul canonized Kolbe on October 10, 1982, declaring him a martyr of charity and the “Patron Saint of Our Difficult Century”.

The decision to declare Kolbe a martyr was contested and controversial. To be declared a martyr, Kolbe would have needed to have died due to odium fidei (hatred of the faith). At his beatification, Kolbe’s death was declared as resulting from his act of Christian charity. Pope John Paul II was invested in framing the Nazi hatred of categories of humanity as a hatred of the faith and overturned previous Vatican decisions in declaring his death as being like previous historical examples of martyrdom. He is listed as among the Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem. Holocaust scholars have documented examples of antisemitism in his published writing.

Losing Faith?

Although the focus on faith during and after the Holocaust is most often on Jewish survivors, we should consider the impact of the Holocaust on Christians as well. The persecution of Christians during the war, either as Christians or for reasons unrelated to religious identity, also led to profound existential crises that, for persons of faith, were necessarily framed in religious terms.

In a prison block that usually held non-Jewish prisoners in the Mauthausen concentration camp, these words were scratched into a wall.

Mein Gott, warum hast du mich verlassen!

Sich fügen, heißt lügen.

Wenn es einen Gott gibt, muß er mich um Verzeihung bitten.

My God why have you forsaken me?

To bend, means to lie.

If there is a god, he must beg for my forgiveness.

Described in the following documentary film: Anneliese Wiesler, Director. Rückkehr unerwünscht Konzentrationslager Mauthausen [Undesirable Return Mauthausen concentration camp]/ SHB Medienzentrum, documentary film, 45 mins. (199?), Library Call Number: VHS-0579, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Although the words are often attributed to a Jewish prisoner, that is unlikely given the population that was usually incarcerated in this block. The words “My God why have you forsaken me” have their origins in Psalm 22 in the Hebrew Bible, but are much more familiar as spoken by Jesus on the Cross, crying out to God in both Matthew 27:46 and Mark 15:34.

While this prisoner may have lost faith, the many stories of Christian rescuers and of Christians who faced torture and death with their faith are inspiring to many Christians around the world.

Were the Nazis Christian?

In the concluding chapter of Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919-1945, Richard Steigmann-Gall reflects on the powerful impulse to maintain that the Nazis were not Christians.

“By detaching Christianity from the crimes of its adherents, we create a Christianity above history, a Christianity whose teachings need not ultimately be investigated. Seen in this light, those who have committed such acts must have misunderstood Christianity, or worse yet purposefully misused it for their own ends. ‘Real Christians’ do not commit such crimes. ‘Real Christianity’ is about loving one’s neighbor and the righteousness of the meek. But there is another side of the coin. As the theologian Richard Rubenstein puts it, ‘The world of the death camps and the society it engenders reveals the progressively intensifying night side of Judeo-Christian civilization. Civilization means slavery, wars, exploitation, and death camps. It also means medical hygiene, elevated religious ideas, beautiful art, and exquisite music.’ Christianity, in other words, may be the source of some of the same darkness it abhors.’’

Richard Steigmann-Gall. The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919-1945. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003): 267.