Module 5: Memory and the Holocaust

Culture and the Holocaust

In the final section of this module, we will reflect on how and why the Holocaust became a subject of cultural attention. Specifically, we will look to film and music as a way of understanding the relationship between culture and the Holocaust.

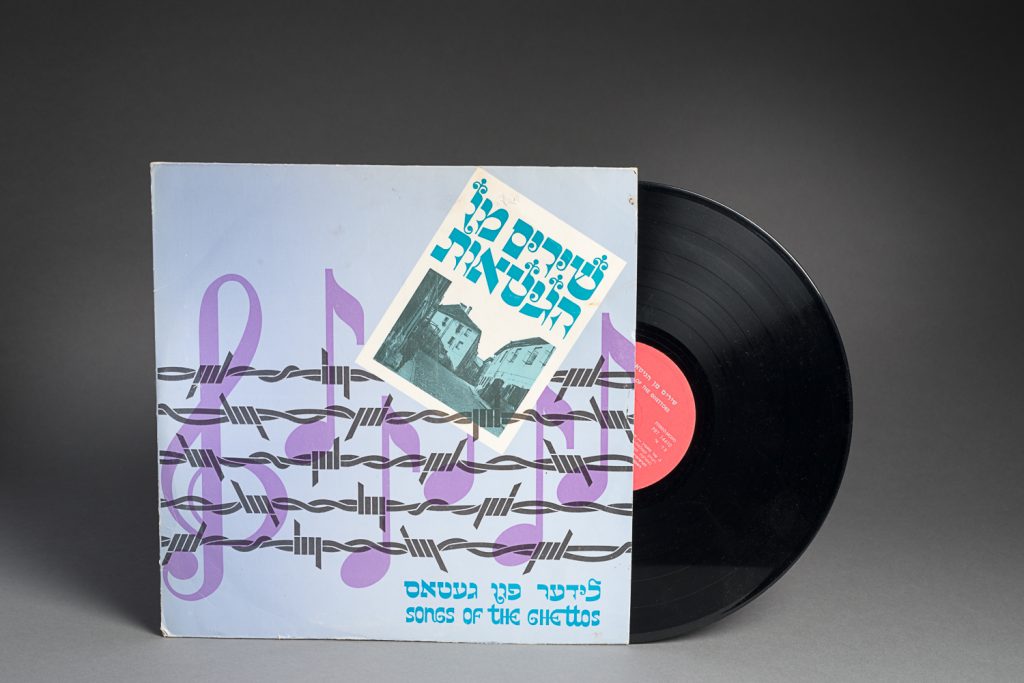

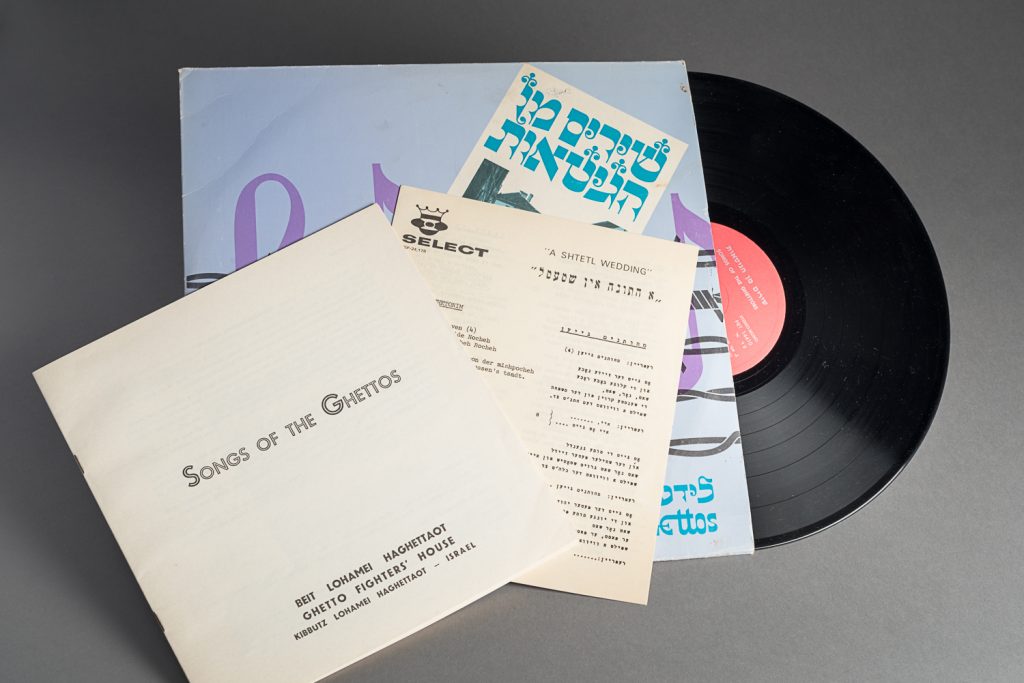

Culture and Commemoration

In this lecture, Dr. Tesler-Mabé explains the evolution of Holocaust remembrance through cultural expressions, like film and music, from the end of the Second World War to the 1970s. After listening to this lecture, watch the following video clip and then consider why director Naomi Jaye decided to film the 2013 movie in Yiddish. To conclude, read more about the Terezin ghetto and consider the way in which music became a means by which Holocaust survivors, like composer Hans Krása, negotiated their experience and how they also shared it with others.

The Pin (Di Shpilke)

“Neither of them [the lead actors] knew Yiddish coming into the film, and by the end they were texting one another using Yiddish words.” —Naomi Jaye

The Pin, directed by Naomi Jaye, (2013; Canada: Main Street Films, 982 Films, and al.), DVD.

The Toronto director and filmmaker, Naomi Jaye chose to have the English script of the film translated into Yiddish to keep it as authentic as possible. With The Pin, Naomi Jaye made the first Yiddish-language feature to be ever filmed in Canada.

Finding actors in Canada that were both fluent speakers and were willing to be in a film with some nudity was, however, harder than she expected. She issued a casting call for actors fluent in at least one Eastern European language. She explained in her interview with The Times of Israel that she “figured they would be able to get their mouths around the Yiddish words.” This is how the Lithuanian Canadian dancer and actress Milda Gecaite (Leah) learned Yiddish, a language she had not heard of before the audition. She remembers doing the first audition in English and feeling that she would not be able to perform in a foreign language for the second audition. Just like Jaye, the director, Gecaite was surprised at her capacity to mimic the sounds of the words in the script so that the dialogues would be clear and understandable. Just like Gecaite, the Ukranian Canadian actor Grisha Pasternak (Jacob) was surprised to be asked to learn Yiddish for the role in a Canadian film. For their role, both actors took months of language lessons.

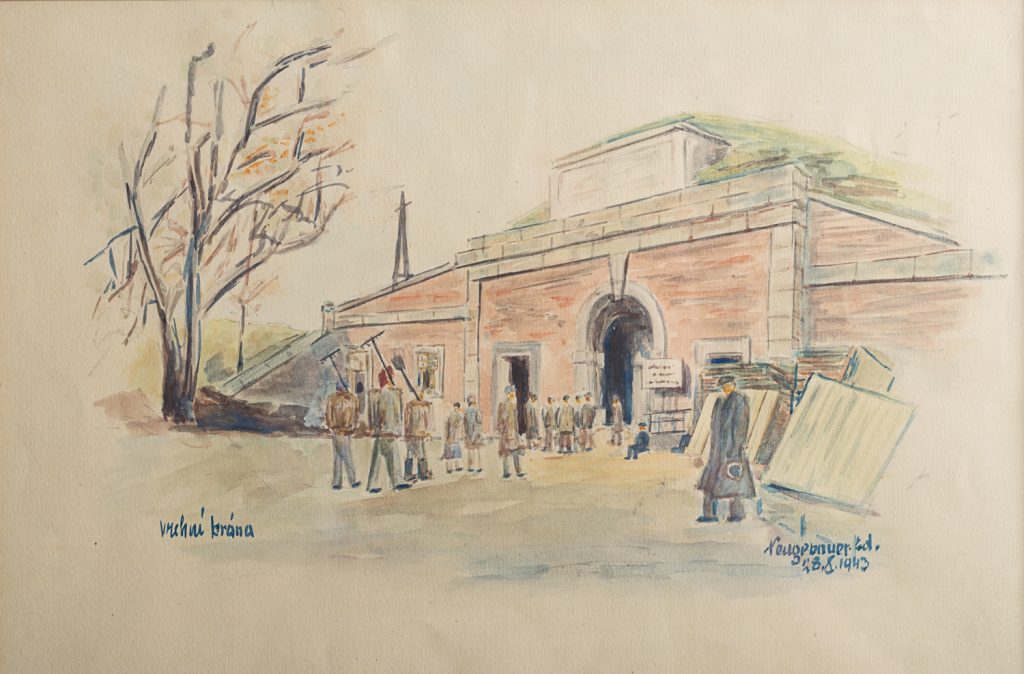

Terezin

The Nazis had them create artworks like this one to show the “good” living conditions inside ghettos. Many of them also used this access to art supplies to make clandestine paintings that revealed the reality of their conditions. This act served as a means of resistance and could be severely punished. —Montreal Holocaust Museum.

The Theresienstadt ghetto was established in the city of Terezin in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in November 1941 and existed for four years until it was liquidated in May 1945 by Nazi authorities. It was primarily used as both a transit and labour camp from which Jewish prisoners were later deported to concentration camps across Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe.

In January 1942, Neugebauer became one of the many Jewish artists that were deported to Terezin. Created to camouflage the treatment suffered in the camps for the public opinion, Theresienstadt allowed its inmates to maintain their cultural activities for the purpose of creating official Nazi propaganda that idealized the living conditions within Jewish ghettos across Nazi-occupied Europe. Jewish artists from occupied land as well as from Germany who had been deported to this camp-ghetto were encouraged to take part in concerts, plays, poetry readings, etc. The watercolour painting above was created by Edvard Neugebauer on August 28, 1943. A year after the completion of this painting, Neugebauer was transferred from Terezin to Auschwitz on September 28, 1944, where he was ultimately killed.