9.2 Cognitive and Personal-Social Dispositions

In this section:

Cognitive Dispositions

Cognitive dispositions refer to general patterns of mental processes that impact how people respond and react to the world around them. These dispositions (or one’s natural mental or emotional outlook) take on several different forms. For our purposes, we’ll briefly examine the four identified by John Daly (2011): locus of control, cognitive complexity, authoritarianism/dogmatism, and emotional intelligence.

Locus of Control

As we have previous learned, individuals differ with respect to how much control they perceive they have over their behaviour and life circumstances. People with an internal locus of control believe that they can control their behavior and life circumstances. For example, people with an internal locus of control would believe that their careers and choice of job are ultimately a product of their behaviors and decisions.The opposite is an external locus of control, or the belief that an individual’s behavior and circumstances exist because of forces outside the individual’s control. An individual with an external locus of control might believe that their career is a matter of luck or divine intervention. This individual would also be more likely to blame outside forces if their work life isn’t going as desired. Our locus of control can also impact how much control we perceive we have in conflict and our belief that we can be part of the solution. For example, Dijkstra et al. (2011) found that individuals with an internal locus of control were more likely to engage in active problem-solving when they encountered conflict in the workplace.

Cognitive Complexity

According to John Daly (2002), “cognitive complexity has been defined in terms of the number of different constructs an individual has to describe others (differentiation), the degree to which those constructs cohere (integration), and the level of abstraction of the constructs (abstractiveness)” (p. 144). By differentiation, we are talking about the number of distinctions or separate elements an individual can utilize to recognize and interpret an event. For example, in the world of communication, someone who can attend to another individual’s body language to a great degree can differentiate large amounts of nonverbal data in a way to understand how another person is thinking or feeling. Someone low in differentiation may only be able to understand a small number of pronounced nonverbal behaviors.

Integration, on the other hand, refers to an individual’s ability to see connections or relationships among the various elements they has differentiated. It’s one thing to recognize several unique nonverbal behaviors, but it’s the ability to interpret nonverbal behaviors that enables someone to be genuinely aware of someone else’s body language. It would be one thing if I could recognize that someone is smiling, an eyebrow is going up, the head is tilted, and someone’s arms are crossed in front. Still, if I cannot see all of these unique behaviors as a total package, then I’m not going to be able to interpret this person’s actual nonverbal behavior.

The last part of Daly’s definition involves the ability to see levels of abstraction. Abstraction refers to something which exists apart from concrete realities, specific objects, or actual instances. For example, if someone to come right out and verbally tell you that they disagrees with something you said, then this person is concretely communicating disagreement, so as the receiver of the disagreement, it should be pretty easy to interpret the disagreement. On the other hand, if someone doesn’t tell you they disagrees with what you’ve said but instead provides only small nonverbal cues of disagreement, being able to interpret those theoretical cues is attending to communicative behavior that is considerably more abstract.

Overall, cognitive complexity is a critical cognitive disposition because it directly impacts interpersonal relationships. According to Brant Burleson and Scott Caplan (1998, p. 239) cognitive complexity impacts several interpersonal constructs:

- Form more detailed and organized impressions of others;

- Better able to remember impressions of others;

- Better able to resolve inconsistencies in information about others;

- Learn complex social information quickly; and

- Use multiple dimensions of judgment in making social evaluations.

In essence, these findings clearly illustrate that cognitive complexity is essential when determining the extent to which an individual can understand and make judgments about others in interpersonal interactions.

Authoritarianism/Dogmatism

According to Jason Wrench, James C. McCroskey, and Virginia Richmond (2008), two personality characteristics that commonly impact interpersonal communication are authoritarianism and dogmatism. Authoritarianism is a form of social organization where individuals favor absolute obedience to authority (or authorities) as opposed to individual freedom. The highly authoritarian individual believes that individuals should just knowingly submit to their power. Individuals who believe in authoritarianism but are not in power believe that others should submit themselves to those who have power.

Dogmatism, although closely related, is not the same thing as authoritarianism. Dogmatism is defined as the inclination to believe one’s point-of-view as undeniably true based on faulty premises and without consideration of evidence and the opinions of others. Individuals who are highly dogmatic believe there is generally only one point-of-view on a specific topic, and it’s their point-of-view. Highly dogmatic individuals typically view the world in terms of “black and white” while missing most of the shades of grey that exist between. Dogmatic people tend to force their beliefs on others and refuse to accept any variation or debate about these beliefs, which can lead to strained interpersonal interactions. Both authoritarianism and dogmatism “tap into the same broad idea: Some people are more rigid than others, and this rigidity affects both how they communicate and how they respond to communication” (Daly, 2002, p. 144).

Right-Wing Authoritarianism

One closely related term that has received some minor exploration in interpersonal communication is right-wing authoritarianism. According to Bob Altemeyer (2006) in his book The Authoritarians, right-wing authoritarians (RWAs) tend to have three specific characteristics:

- RWAs believe in submitting themselves to individuals they perceive as established and legitimate authorities.

- RWAs believe in strict adherence to social and cultural norms.

- RWAs tend to become aggressive towards those who do not submit to established, legitimate authorities and those who violate social and cultural norms.

Please understand that Altemeyer’s use of the term “right-wing” does not imply the same political connotation that is often associated with it in the North America. As Altemeyer explains, “Because the submission occurs to traditional authority, I call these followers right-wing authoritarians. I’m using the word “right” in one of its earliest meanings, for in Old English ‘right’(pronounced ‘writ’) as an adjective meant lawful, proper, correct, doing what the authorities said of others” (Altemeyer, 2006, p. 9). Under this definition, right-wing authoritarianism is the perfect combination of both dogmatism and authoritarianism.

Right-wing authoritarianism has been linked to several interpersonal variables. For example, parents/guardians who are RWAs are more likely to believe in a highly dogmatic approach to parenting. In contrast, those who are not RWAs tend to be more permissive in their approaches to parenting (Manuel, 2006). Another study found that men with high levels of RWA were more likely to have been sexually aggressive in the past and were more likely to report sexually aggressive intentions for the future (Walker et al., 1993) Men with high RWA scores tend to be considerably more sexist and believe in highly traditional sex roles, which impacts how they communicate and interact with women (Altemeyer, 2006). Overall, RWA tends to negatively impact interpersonal interactions with anyone who does not see an individual’s specific world view and does not come from their cultural background.

Emotional Intelligence

As discussed in Chapter 7, emotional intelligence is essential for successful relationships and conflict management (Goleman, 1995). Emotional intelligence (EQ) is important for interpersonal communication because individuals who are higher in EQ tend to be more sociable and less socially anxious. As a result of both sociability and lowered anxiety, high EQ individuals tend to be more socially skilled and have higher quality interpersonal relationships.

Affective Orientation

A closely related communication construct originally coined by Melanie and Steven Booth-Butterfield is affective orientation(Booth-Butterfield & Booth-Butterfield, 1994) As it is conceptualized by the Booth-Butterfields, affective orientation (AO) is “the degree to which people are aware of their emotions, perceive them as important, and actively consider their affective responses in making judgments and interacting with others” (Booth-Butterfield & Booth-Butterfield, 1994, p. 332). Under the auspices of AO, the general assumption is that highly affective-oriented people are (1) cognitively aware of their own and others’ emotions, and (2) can implement emotional information in communication with others. Not surprisingly, the Booth-Butterfields found that highly affective-oriented individuals also reported greater affect intensity in their relationships.

Melanie and Steven Booth-Butterfield (1996) later furthered their understanding of AO by examining it in terms of how an individual’s emotions drive their decisions in life. As the Booth-Butterfields explain, in their further conceptualization of AO, they “are primarily interested in those individuals who not only sense and value their emotions but scrutinize and give them weight to direct behavior” (p. 159). In this sense, the Booth-Butterfields are expanding our notion of AO by explaining that some individuals use their emotions as a guiding force for their behaviors and their lives. On the other end of the spectrum, you have individuals who use no emotional information in how they behave and guide their lives. Although relatively little research has examined AO, the conducted research indicates its importance in interpersonal relationships. For example, in one study, individuals who viewed their parents/guardians as having high AO levels reported more open communication with those parents/guardians (Booth-Butterfield & Sidelinger, 1997).

Personal-Social Dispositions

Social-personal dispositions refer to general patterns of mental processes that impact how people socially relate to others or view themselves. All of the following dispositions impact how people interact with others, but they do so from very different places. Without going into too much detail, we are going to examine the seven personal-social dispositions identified by John Daly (2011).

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem consists of your sense of self-worth and the level of satisfaction you have with yourself; it is how you feel about yourself. A good self-image raises your self-esteem; a poor self-image often results in poor self-esteem, lack of confidence, and insecurity. Not surprisingly, individuals with low self-esteem tend to have more problematic interpersonal relationships and may have difficulty asserting their needs and boundaries.

Our self-esteem is determined by many factors, including how well we view our own performance and appearance, and how satisfied we are with our relationships with other people (Tafarodi & Swann, 1995). Self-esteem is in part a trait that is stable over time, with some people having relatively high self-esteem and others having lower self-esteem. But self-esteem is also a state that varies day to day and even hour to hour. When we have succeeded at an important task, when we have done something that we think is useful or important, or when we feel that we are accepted and valued by others, our self-concept will contain many positive thoughts and we will therefore have high self-esteem. When we have failed, done something harmful, or feel that we have been ignored or criticized, the negative aspects of the self-concept are more accessible and we experience low self-esteem.

Baumeister and colleagues (2003) conducted an extensive review of the research literature to determine whether having high self-esteem was as helpful as many people seem to think it is. They began by assessing which variables were correlated with high self-esteem and then considered the extent to which high self-esteem caused these outcomes. They found that high self-esteem does correlate with many positive outcomes. People with high self-esteem get better grades, are less depressed, feel less stress, and may even live longer than those who view themselves more negatively. The researchers also found that high self-esteem is correlated with greater initiative and activity; people with high self-esteem just do more things. They are also more more likely to defend victims against bullies compared with people with low self-esteem, and they are more likely to initiate relationships and to speak up in groups. High self-esteem people also work harder in response to initial failure and are more willing to switch to a new line of endeavor if the present one seems unpromising. Thus, having high self-esteem seems to be a valuable resource—people with high self-esteem are happier, more active, and in many ways better able to deal with their environment.

While a high self-esteem is generally healthy, Jennifer Crocker and Lora Park (2004) have identified a potential cost of our attempts to inflate our self-esteem: we may spend so much time trying to enhance our self-esteem in the eyes of others—by focusing on the clothes we are wearing, impressing others, and so forth—that we have little time left to really improve ourselves in more meaningful ways. In some extreme cases, people experience such strong needs to improve their self-esteem and social status that they act in assertive or dominant ways in order to gain it. As in many other domains, then, having positive self-esteem is a good thing, but we must be careful to temper it with a healthy realism and a concern for others. The real irony here is that those people who do show more other- than self-concern, those who engage in more prosocial behavior at personal costs to themselves, for example, often tend to have higher self-esteem anyway (Leak & Leak, 2003).

Narcissism

Ovid’s story of Narcissus and Echo has been passed down through the ages. The story starts with a Mountain Nymph named Echo who falls in love with a human named Narcissus. When Echo reveals herself to Narcissus, he rejects her. In true Roman fashion, this slight could not be left unpunished. Echo eventually leads Narcissus to a pool of water where he quickly falls in love with his reflection. He ultimately dies, staring at himself, because he realizes that his love will never be met.

In modern times, narcissism is defined a personality trait characterized by overly high self-esteem, self-admiration, and self-centeredness. Highly narcissistic individuals are completely self-focused and tend to ignore the communicative needs and emotions of others. In social situations, highly narcissistic individuals strive to be the center of attention. Narcissists tend to agree with statements such as the following:

“I know that I am good because everybody keeps telling me so.”

“I can usually talk my way out of anything.”

“I like to be the center of attention.”

“I have a natural talent for influencing people.”

Anita Vangelisti, Mark Knapp, and John Daly (1990) examined a purely communicative form of narcissism they deemed conversational narcissism. Conversational narcissism is an extreme focusing of one’s interests and desires during an interpersonal interaction while completely ignoring the interests and desires of another person. Vangelisti et al. found four general categories of conversationally narcissistic behavior. First, conversational narcissists inflate their self-importance while displaying an inflated self-image. Some behaviors include bragging, refusing to listen to criticism, praising one’s self, etc. Second, conversational narcissists exploit a conversation by attempting to focus the direction of the conversation on topics of interest to them. Some behaviors include talking so fast others cannot interject, shifting the topic to one’s self, interrupting others, etc. Third, conversational narcissists are exhibitionists, or they attempt to show-off or entertain others to turn the focus on themselves. Some behaviors include primping or preening, dressing to attract attention, being or laughing louder than others, positioning oneself in the center, etc. Lastly, conversational narcissists tend to have impersonal relationships. During their interactions with others, conversational narcissists show a lack of caring about another person and a lack of interest in another person. Some common behaviors include “glazing over” while someone else is speaking, looking impatient while someone is speaking, looking around the room while someone is speaking, etc. As you can imagine, people engaged in interpersonal encounters with conversational narcissists are generally highly unsatisfied with those interactions.

Narcissists can be perceived as charming at first, but often alienate others in the long run (Baumeister et al., 2003). They can also make bad romantic partners as they often behave selfishly and are always ready to look for someone else who they think will be a better mate, and they are more likely to be unfaithful than non-narcissists (Campbell & Foster, 2002; Campbell et al., 2002). Narcissists are also more likely to bully others, and they may respond very negatively to criticism (Baumeister et al., 2003). People who have narcissistic tendencies more often pursue self-serving behaviors, to the detriment of the people and communities surrounding them (Campbell et al., 2005). Perhaps surprisingly, narcissists seem to understand these things about themselves, although they engage in the behaviors anyway (Carlson et al., 2011).

Interestingly, scores on measures of narcissistic personality traits have been creeping steadily upward in recent decades in some cultures (Twenge et al., 2008). Given the social costs of these traits, this is troubling news. What reasons might there be for these trends? Twenge and Campbell (2009) argue that several interlocking factors are at work here, namely increasingly child-centered parenting styles, the cult of celebrity, the role of social media in promoting self-enhancement, and the wider availability of easy credit, which, they argue, has lead to more people being able to acquire status-related goods, in turn further fueling a sense of entitlement. As narcissism is partly about having an excess of self-esteem, it should by now come as no surprise that narcissistic traits are higher, on average, in people from individualistic versus collectivistic cultures (Twenge et al., 2008).

Machiavellianism

In 1513, Nicolo Machiavelli wrote a text called The Prince. Although Machiavelli dedicated the book to Lorenzo di Piero de’ Medici, who was a member of the ruling Florentine Medici family, the book was originally scribed for Lorenzo’s uncle. In The Prince, Nicolo Machiavelli unabashedly describes how he believes leaders should keep power. First, he notes that traditional leadership virtues like decency, honor, and trust should be discarded for a more calculating approach to leadership. Most specifically, Machiavelli believed that humans were easily manipulated, so ultimately, leaders can either be the ones influencing their followers or wait for someone else to wield that influence in a different direction.

In 1970, two social psychologists named Richard Christie and Florence Geis decided to see if Machiavelli’s ideas were still in practice in the 20th Century. The basic model that Christie and Geis proposed consisted of four basic Machiavellian characteristics:

- Lack of affect in interpersonal relationships (relationships are a means to an end);

- Lack of concern with conventional morality (people are tools to be used in the best way possible);

- Rational view of others not based on psychopathology (people who actively manipulate others must be logical and rational); and

- Focused on short-term tasks rather than long-range ramifications of behavior (these individuals have little ideological/organizational commitment).

Interpersonally, highly Machiavellian people tend to see people as stepping stones to get what they want. If talking to someone in a particular manner makes that other people feel good about themself, the Machiavellian has no problem doing this if it helps the Machiavellian get what they wants. Ultimately, Machiavellian behavior is very problematic. In interpersonal interactions where the receiver of a Machiavellian’s attempt of manipulation is aware of the manipulation, the receiver tends to be highly unsatisfied with these communicative interactions. However, someone who is truly adept at the art of manipulation may be harder to recognize than most people realize.

Empathy

As we have previously learned, empathy is the ability to recognize and mutually experience another person’s attitudes, emotions, experiences, and thoughts. Highly empathic individuals have the unique ability to connect with others interpersonally, because they can truly see how the other person is viewing life. Individuals who are unempathetic generally have a hard time taking or seeing another person’s perspective, so their interpersonal interactions tend to be more rigid and less emotionally driven. Generally speaking, people who have high levels of empathy tend to have more successful and rewarding interactions with others when compared to unempathetic individuals. Furthermore, people who are interacting with a highly empathetic person tend to find those interactions more satisfying than when interacting with someone who is unempathetic. The ability to take perspective and show genuine concern and connection to others is a highly valuable skill in interpersonal interactions, especially during the conflict process.

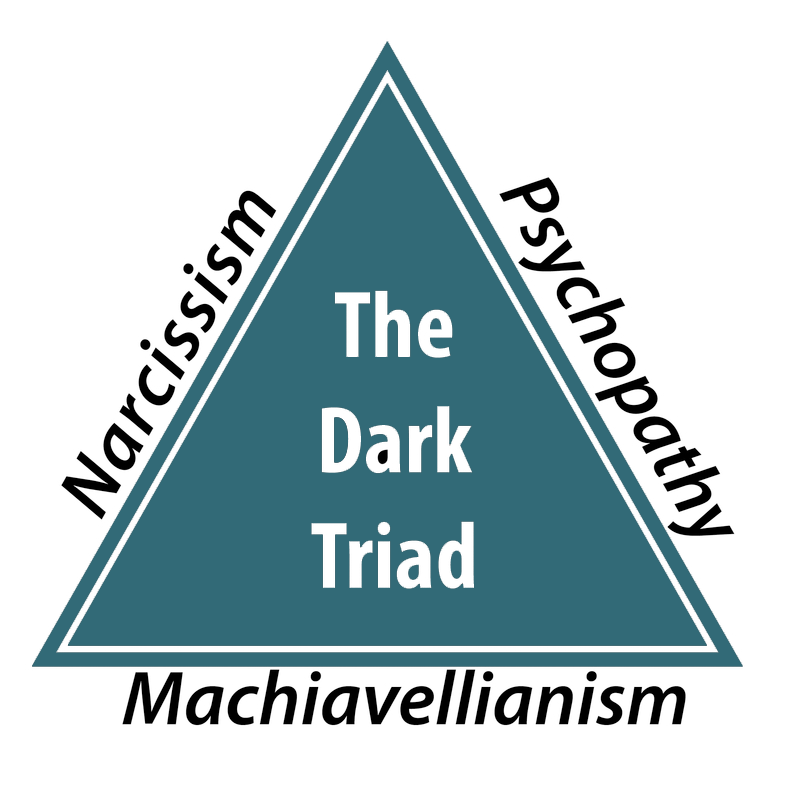

Individuals with low levels of empathy may exhibit patterns of psychopathy. Together psychopathy, Machiavellianism and narcissism comprise what social psychologists call the Dark Triad.

Consider This: Dealing with Someone with Narcissistic Tendencies

The Grey Rocking Technique

When a coworker is exhibiting signs of narcissism (e.g., creating unnecessary drama, demanding to be the center of attention, or constantly seeking approval), it can be exhausting to deal with daily. This individual may not have the capacity or the motivation to deal with conflict in a respectful manner. In some situations, reporting inappropriate behaviour to relevant managers or organizational structures may be necessary. Later in the book, we will talk about bullying and harassment. If the behaviour is more of an annoyance, Sword and Zimbardo (2022) suggest a strategy called “grey rocking”.

When a coworker is exhibiting signs of narcissism (e.g., creating unnecessary drama, demanding to be the center of attention, or constantly seeking approval), it can be exhausting to deal with daily. This individual may not have the capacity or the motivation to deal with conflict in a respectful manner. In some situations, reporting inappropriate behaviour to relevant managers or organizational structures may be necessary. Later in the book, we will talk about bullying and harassment. If the behaviour is more of an annoyance, Sword and Zimbardo (2022) suggest a strategy called “grey rocking”.

This technique encourages you to think about your own behaviour and to model the grey rock pictured above. It’s unmoving and dull. In much the same way, grey rocking in communication involves becoming uninteresting. Sword and Zimbardo suggest keeping conversations brief, not providing lot of elaboration when questions are asked, and using non-verbal behaviours (e.g., lack of eye contact) to show your disinterest or disengagement.

The individual will learn that their need for attention won’t be met by you and change unwanted behaviours or, at the very least, that you will feel less emotionally depleted by encounters with this person.

References

Sword, R. K. M., & Zimbardo, P. (2022, November 3). When dealing with a narcissist, the “gray rock” approach might help. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/the-time-cure/202211/when-dealing-narcissist-the-gray-rock-approach-might-help

Self-Monitoring

The last of the personal-social dispositions is referred to as self-monitoring. In 1974 Mark Snyder developed his basic theory of self-monitoring, which proposes that individuals differ in the degree to which they can control their behaviors following the appropriate social rules and norms involved in interpersonal interaction. In this theory, Snyder proposes that there are some individuals adept at selecting appropriate behavior in light of the context of a situation, which he deems high self-monitors. High self-monitors want others to view them in a precise manner (impression management), so they enact communicative behaviors that ensure suitable or favorable public appearances. On the other hand, some people are merely unconcerned with how others view them and will act consistently across differing communicative contexts despite the changes in cultural rules and norms. Snyder called these people low self-monitors.

Interpersonally, high self-monitors tend to have more meaningful and satisfying interpersonal interactions with others. Conversely, individuals who are low self-monitors tend to have more problematic and less satisfying interpersonal relationships with others. In romantic relationships, high self-monitors tend to develop relational intimacy much faster than individuals who are low self-monitors. Furthermore, high self-monitors tend to build lots of interpersonal friendships with a broad range of people. Low-self-monitors may only have a small handful of friends, but these friendships tend to have more depth. Furthermore, high self-monitors are also more likely to take on leadership positions and get promoted in an organization when compared to their low self-monitoring counterparts. Overall, self-monitoring is an important dispositional characteristic that impacts interpersonal relationships.

Adapted Works

“Intrapersonal Communication” in Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“The Self” in Principles of Social Psychology – 1st International H5P Edition by Dr. Rajiv Jhangiani and Dr. Hammond Tarry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Psychopathy” by Chris Patrick is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

References

Altemeyer, B. (2006). The Authoritarians. www.theauthoritarians.org

Anderson, C. A., Miller, R. S., Riger, A. L., Dill, J. C., & Sedikides, C. (1994). Behavioral and chategorlogical attributional styles as predictors of depression and loneliness: Review, refinement, and test. Journal of Personality and Social Relationships, 66(3), 549-558.

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(1), 1–44.

Booth-Butterfield, M., & Booth-Butterfield, S. (1994). The affective orientation to communication: Conceptual and empirical distinctions. Communication Quarterly, 42(4), 331-344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379409369941

Booth-Butterfield, M., & Booth-Butterfield, S. (1996). Using your emotions: Improving the measurement of affective orientation. Communication Research Reports, 13(2), 157-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824099609362082

Booth-Butterfield, M., & Sidelinger, R. J. (1997). The relationship between parental traits and open family communication: Affective orientation and verbal aggression. Communication Research Reports, 14(4), 408-417. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824099709388684

Burleson, B. R., & Caplan, S. E. (1998). Cognitive complexity. In J. C. McCroskey, J. A. Daly, M. M. Martin, & M. J. Beatty (Eds.), Communication and personality: Trait perspectives (pp. 233-286). Hampton Press.

Campbell, W., Bush, C., Brunell, A. B., & Shelton, J. (2005). Understanding the social costs of narcissism: The case of the tragedy of the commons. Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(10), 1358-1368. doi:10.1177/0146167205274855

Campbell, W. K., & Foster, C. A. (2002). Narcissism and commitment in romantic relationships: An investment model analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 484–495.

Campbell, W. K., Rudich, E., & Sedikides, C. (2002). Narcissism, self-esteem, and the positivity of self-views: Two portraits of self-love. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 358–368.

Carlson, E. N., Vazire, S., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2011). You probably think this paper’s about you: Narcissists’ perceptions of their personality and reputation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 185–201.

Christie, R., & Geis, F. L. (1970). Studies in Machiavellianism. Academic Press.

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2004). The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 392–414.

Daly, J. A. (2002). Personality and interpersonal communication. In M. L. Knapp & J. A. Daly (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interpersonal communication (3rd ed., pp. 133-180). Sage.

Daly, J. A. (2011). Personality and interpersonal communication. In M. L. Knapp & J. A. Daly (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interpersonal communication (4th ed., pp. 131-167). Sage.

, A. (2011) Reducing conflict-related employee strain: The benefits of an internal locus of control and a problem-solving conflict management strategy, Work & Stress, 25(2), 167-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2011.593344

Goleman, D. P. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ for character, health and lifelong achievement. Bantam Books.

Leak, G. K., & Leak, K. C. (2003). Adlerian Social Interest and Positive Psychology: A Conceptual and Empirical Integration. The Journal of Individual Psychology, 62(3), 207-223.

Manuel, L. (2006). Relationship of personal authoritarianism with parenting styles. Psychological Reports, 98(1), 193-198. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.98.1.193-198

Patrick, C. (2022). Psychopathy. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. DEF publishers. http://noba.to/ysg8mu9w

Snyder, M. (1974). Self-monitoring of expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30(4), 526-537. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037039

Tafarodi, R. W., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (1995). Self-liking and self-competence as dimensions of global self-esteem: Initial validation of a measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65(2), 322–342.

Twenge, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2009). The narcissism epidemic. Free Press.

Twenge, J. M., Konrath, S., Foster, J. D., Campbell, W., & Bushman, B. J. (2008). Egos inflating over time: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal Of Personality, 76(4), 875-902. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00507.x

Vangelisti, A. L., Knapp, M. L., & Daly, J. A. (1990). Conversational narcissism. Communication Monographs, 57(4), 251-274. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759009376202

Walker, W. D., Rowe, R. C., & Quinsey, V. L. (1993). Authoritarianism and sexual aggression. Journal Of Personality & Social Psychology, 65(5), 1036-1045.

Wrench, J. S., McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (2008). Human communication in everyday life: Explanations and applications. Allyn & Bacon.