8.2 Meeting Needs Through Communication Climate

Needs and Communication Climate

One way that we can help ensure that safety, social and esteem needs are being consistently met in the workplace is by creating a positive communication climate in which people feel seen, heard and valued. In this section, we will talk more about the nature of communication climate and how to generate messages that help others meet their needs.

In this section:

Principles of Communication Climate

Communication climate is the “overall feeling or emotional mood between people” (Wood, 1999). If you dread going to visit your family during the holidays because of tension between you and your sister, or you look forward to dinner with a particular set of friends because they make you laugh, you are responding to the communication climate—the overall mood that is created because of the people involved and the type of communication they bring to the interaction.

In this section we will discuss the five principles of communication climate: messages contain relational subtexts that can be felt; climate is conveyed through words, action, and non-action; climate is perceived; climate is determined by social and relational needs; and relational messages are multi-leveled.

Messages Contain Relational Subtexts That Can Be Felt

In addition to generating and perceiving meaning in communicative interactions, we also subtly (and sometimes not so subtly) convey and perceive the way we feel about each other. Almost all messages operate on two levels: content and relational. As a reminder, the content is the substance of what’s being communicated (the what of the message). The relational dimension isn’t the actual thing being discussed and instead can reveal something about the relational dynamic existing between you and the other person (the who of the message). We can think of it as a kind of subtext, an underlying (or hidden) message that says something about how the parties feel toward one another. For example, when deciding on a topic for a group project at school, your group member might politely suggest, “I’d like to study agile project management, how about you?” The content of the message is about what they want to study. The relational subtext is subtle but suggests your group values your input and wants to share decision-making control. The climate of this interaction is likely to be neutral or warm. However, consider how the relational subtext changes if group member insists (with a raised voice and a glare): “We are RESEARCHING AGILE PROJECT MANAGEMENT!” The content is still about what they want to study. But what is the subtext now? In addition to the content, they seem to be sending a relational message of dominance, control, and potential disrespect for your needs and wants. You might be hearing an additional message of “I don’t care about you,” which is likely to feel cold, eliciting a negative emotional reaction such as defensiveness or sadness.

Climate is Conveyed through Words, Action, and Non-Action

Relational subtexts can be conveyed through direct words and actions. A student making a complaint to an instructor can be worded with respect, as in “Would you have a few minutes after class to discuss my grade?” or without, as in “I can’t believe you gave me such a terrible grade, and we need to talk about it right after class!” We can often find more of the relational meaning in the accompanying and more indirect nonverbals—in the way something is said or done. For example, two of your coworkers might use the exact same words to make a request of you, but the tone, emphasis, and facial expression will change the relational meaning, which influences the way you feel. The words “can you get this done by Friday” will convey different levels of respect and control depending upon the nonverbal emphasis, tone, and facial expressions paired with the verbal message. For example, the request can be made in a questioning tone versus a frustrated or condescending one. Additionally, a relational subtext might also be perceived by what is NOT said or done. For example, one coworker adds a “thanks” or a “please” and the other doesn’t. Or, one coworker shows up to your birthday coffee meetup and the other doesn’t. What do these non-actions suggest to you about the other person’s feelings or attitude towards you? Consider for a moment some past messages (and non-messages) that felt warm or cold to you.

Climate is Perceived

Relational meanings are not inherent in the messages themselves. They are not literal, and they are not facts. The subtext of any communicative message is in the eye of the beholder. The relational meaning can be received in ways that were unintentional. Additionally, like content messages, relational messages can be influenced by what we attend to and by our expectations. They also stand out more if they contrast with what you normally expect or prefer.

You might interpret your project partner’s insistence on researching a certain topic to mean they are bossy. However, your partner might have perceived you to be the bossy one and is attempting to regain the loss of decision control. Control could be exerted because doing so is the accepted relational dynamic between you, or it could be a frustrated reaction to a frequent loss of decision control, which they want to regain. Here, it needs to be noted that the relational message someone hears at any given time is a perception and doesn’t necessarily mean the message received was the message intended. Meanings will depend on who is delivering it and in what context. Cultural and co-cultural context will also impact the way a message is interpreted.

Climate is Determined by Social and Relational Needs

While relational messages can potentially show up in dozens of different communicative forms, they generally fall into categories that align with specific types of human social needs that vary from person to person and situation to situation. In addition to physical needs, such as food and water, human beings have social and relational needs that can have negative consequences if ignored. Negative consequences can range from frustrating work days to actual death (in cases of infants not getting human touch and attention and the elderly who suffer in isolation). Scholars categorize social needs in many different ways. We are more likely to develop relationships with people who meet one or more of three basic interpersonal needs: affection, control, and belonging. We want to be liked or loved. We want to be able to influence others and our own environments (at least somewhat). We want to feel included. Each need exists on a continuum from low to high, with some people needing only a little of one and more of another. The level of need also varies by context, with some situations calling for more affection (e.g., romantic relationships) and others calling for less (e.g., workplace).

Another framework for categorizing needs comes from a nonviolent communication approach used by mediators, negotiators, therapists, and businesses across the world. This approach focuses on compassion and collaboration and categorizes human needs with more detail and scope. For example, categories include freedom, connection, community, play, integrity, honesty, peace, and the needs to matter and be understood. Some of these needs are summarized in the table below. When people from all cultures and all walks of life all over the world are asked “Do you need these to thrive?” the answer—with small nuances—is always “yes” (Sofer, 2018).

Table 8.1 Nonviolent Communication Approach

| Area | Need |

|---|---|

| Autonomy | to choose ones dreams, goals, values |

| to choose ones plan for fulfilling ones dreams, goals, values | |

| Celebration | to celebrate the creation of life and dreams fulfilled |

| to celebrate losses: loved ones, dreams, etc. (mourning) | |

| Play | fun |

| laughter | |

| Spiritual Communion | beauty |

| harmony | |

| inspiration | |

| order | |

| peace | |

| Physical Nurturance | air |

| food | |

| movement, exercise | |

| protection from life-threatening forms of life: viruses, bacteria, insects, predatory animals | |

| rest | |

| sexual expression | |

| shelter | |

| touch | |

| water | |

| Integrity | authenticity |

| creativity | |

| meaning | |

| self-worth | |

| Interdependence | acceptance |

| appreciation | |

| closeness | |

| community | |

| consideration | |

| contribution to the enrichment of life (to exercise ones power by giving that which contributes to life) | |

| emotional safety | |

| empathy | |

| honesty (the empowering honest that enables us to learn from our limitations) | |

| love | |

| reassurance | |

| respect | |

| support | |

| trust | |

| understanding | |

| warmth | |

| Source: Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life 2nd Ed by Dr. Marshall B. Rosenberg, 2003 published by PuddleDancer Press and Used with Permission. For more information visit www.CNVC.org and www.NonviolentCommunication.com. Reproduced from Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | |

During interactions, we detect on some level whether the person with whom we are communicating is meeting a particular need, such as the need for respect. We may not really be aware, on a conscious level, of why we feel cold toward a coworker. But, it is likely that the coworker’s jokes, eye rolls, and criticisms toward you feel like a relational message of inferiority or disrespect. In this case, your unmet need for dignity, competence, respect, or belonging may be contributing to your cold reaction toward this person. When other people’s messages don’t meet our needs in whole or in part, we tend to have an emotionally cold reaction. When messages do meet our needs, we tend to feel warm.

Consider how needs may be met (or not met) when you are in a disagreement of opinion with someone else. For example, needs may be met if we feel heard by the other and not met if we feel disrespected when we present our opinion. In a different example, consider all the different ways you could request that someone turn the music down. You could do both of these things with undertones (relational subtexts) of superiority, anger, dominance, ridicule, coldness, distance, etc. Or you could do them with warmth, equality, playfulness, shared control, respect, trust, etc.

Relational Messages are Multi-Leveled

On one level, we want to feel that our social needs are met and we hope that others in our lives will meet them through their communication, at least in part. On another level, though, we are concerned with how we are perceived; the self-image we convey to others is important to us. We want it to be apparent to others that we belong, matter, are respected, understood, competent, and in control of ourselves. Some messages carry relational subtexts that harm or threaten our self-image, while others confirm and validate it.

To help better understand this second level of relational subtexts, let’s discuss the concept of “face needs.” Face refers to our self-image when communicating with others (Ting-Toomey, 2005; Brown and Levinson, 1987; Lim and Bowers, 1991). It does not refer to our physical face, but more of an unsaid portrayal of the image that we want to project to others, and sometimes even to ourselves. Most of us are probably unaware of the fact that we are frequently negotiating this face as we interact with others. However, on some level, whether we are aware of it or not, many of our social needs relate to the way we want to be perceived by others. Specifically, we not only want to feel included in particular groups, we also want to be seen as someone who belongs. We want to feel capable and competent, but we also want others to think we are capable and competent. We want to experience a certain level of autonomy, but we also want to be seen as free from the imposition of others.

Communication subtexts such as disrespect tend to threaten our face needs, while other behaviors such as the right amount of recognition support them. Once again, we can apply the temperature analogy here. When we perceive our “face” to be threatened, we may feel cold. When our face needs are honored, we may feel warm. Effective communication sometimes requires a delicate dance that involves addressing, maintaining, and restoring our own face and that of others simultaneously.

Because both our own needs and the needs of others play an important role in communication climate, throughout the rest of this section we will utilize the following three general categories when we refer to social needs that can be addressed through communication:

- Need for Connection: belonging, inclusion, acceptance, warmth, kindness

- Need for Freedom: autonomy, control, freedom from imposition by others, space, privacy

- Need for Meaning: competence, capability, dignity, worthiness, respect, to matter, to be understood

Confirming and Disconfirming Messages

Positive and negative climates can be understood by looking at confirming and disconfirming messages. We experience positive climates when we receive messages that demonstrate our value and worth from those with whom we have a relationship. Conversely, we experience negative climates when we receive messages that suggest we are devalued and unimportant. Obviously, most of us like to be in positive climates because they foster emotional safety as well as personal and relational growth. However, it is likely that your relationships fall somewhere between the two extremes.

Confirming Messages

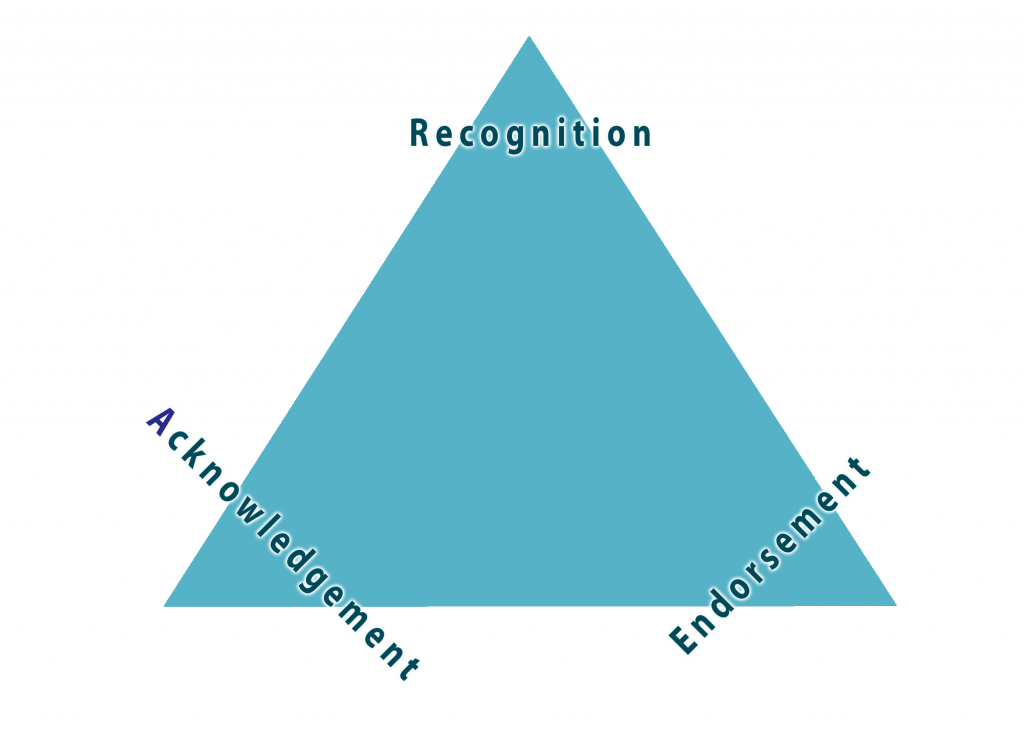

Let’s start by looking at three types of confirming messages:

- Recognition messages either confirm or deny another person’s existence. For example, if a friend enters your home and you smile, hug him, and say, “I’m so glad to see you” you are confirming his existence. On the other hand, if you say “good morning” to a colleague and they ignore you by walking out of the room without saying anything, they may create a disconfirming climate by not recognizing your greeting.

- Acknowledgement messages go beyond recognizing another’s existence by confirming what they say or how they feel. Nodding our head while listening, or laughing appropriately at a funny story, are nonverbal acknowledgment messages. When a friend tells you she had a really bad day at work and you respond with, “Yeah, that does sound hard, do you want to talk about it?”, you are acknowledging and responding to her feelings. In contrast, if you were to respond to your friend’s frustrations with a comment like, “That’s nothing. Listen to what happened to me today,” you would be ignoring her experience and presenting yours as more important.

- Endorsement messages go one step further by recognizing a person’s feelings as valid. Suppose a friend comes to you upset after a fight with his girlfriend. If you respond with, “Yeah, I can see why you would be upset” you are endorsing his right to feel upset. However, if you said, “Get over it. At least you have a girlfriend” you would be sending messages that deny his right to feel frustrated at that moment. While it is difficult to see people we care about in emotional pain, people are responsible for their own emotions. When we let people own their emotions and do not tell them how to feel, we are creating supportive climates that provide a safe environment for them to work through their problems.

Disconfirming Messages

Unfortunately, sometimes when we are interacting with others, disconfirming messages are used. These messages imply, “You don’t exist. You are not valued.” There are seven types of disconfirming messages:

- Impervious response fails to acknowledge another person’s communication attempt through either verbal or nonverbal channels. Failure to return phone calls, emails, and text messages are examples.

- In an interrupting response, one person starts to speak before the other person is finished.

- Irrelevant responses are comments completely unrelated to what the other person was just talking about. They indicate that the listener wasn’t really listening at all, and therefore doesn’t value with the speaker had to say. In each of these three types of responses, the speaker is not acknowledged.

- In a tangential response, the speaker is acknowledged, but with a comment that is used to steer the conversation in a different direction.

- In an impersonal response, the speaker offers a monologue of impersonal, intellectualized, and generalized statements that trivializes the other’s comments (e.g., what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger).

- Ambiguous responses are messages with multiple meanings, and these meanings are highly abstract, or are a private joke to the speaker alone.

- Incongruous responses communicate two messages that seem to conflict along the verbal and nonverbal channels. The verbal channel demonstrates support, while the nonverbal channel is disconfirming. An example might be complimenting someone’s cooking, while nonverbally indicating you are choking.

Consider This

In a study published in the journal Science, researchers reported that the sickening feeling we get when we are socially rejected (being ignored at a party or passed over when picking teams) is real. When researchers measured brain responses to social stress they found a pattern similar to what occurs in the brain when our body experiences physical pain.

In a study published in the journal Science, researchers reported that the sickening feeling we get when we are socially rejected (being ignored at a party or passed over when picking teams) is real. When researchers measured brain responses to social stress they found a pattern similar to what occurs in the brain when our body experiences physical pain.

Specifically, “the area affected is the anterior cingulate cortex, a part of the brain known to be involved in the emotional response to pain” (Fox). The doctor who conducted the study, Matt Lieberman, a social psychologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, said, “It makes sense for humans to be programmed this way. Social interaction is important to survival.” (Nishina et al., 2005).

Supportive and Defensive Climates

Communication is key to developing positive climates. This requires people to attend to the supportive and defensive communication behaviors taking place in their interpersonal relationships and groups. Defensive communication is defined as that communication behavior that occurs when an individual perceives threat or anticipates threat in the group. Those who behave defensively, even though they also give some attention to the common task, devote an appreciable portion of energy to defending themselves. Besides talking about the topic, they think about how they appear to others, how they may be seen more favorably, how they may win, dominate, impress or escape punishment, and/or how they may avoid or mitigate a perceived attack.

Such inner feelings and outward acts tend to create similarly defensive postures in others; and, if unchecked, the ensuing circular response becomes increasingly destructive. Defensive communication behavior, in short, engenders defensive listening, and this, in turn, produces postural, facial, and verbal cues which raise the defense level of the original communicator. Defense arousal prevents the listener from concentrating upon the message. Not only do defensive communicators send off multiple value, motive, and affect cues, but also defensive recipients distort what they receive. As a person becomes more and more defensive, he or she becomes less and less able to perceive accurately the motives, values, and emotions of the sender. Defensive behaviors have been correlated positively with losses in efficiency in communication.

The converse, moreover, also is true. The more “supportive” or defense-reductive the climate, the less the receiver reads into the communication distorted loadings that arise from projections of their own anxieties, motives, and concerns. As defenses are reduced, the receivers become better able to concentrate upon the structure, the content, and the cognitive meanings of the message.

Jack Gibb (1961) developed six pairs of defensive and supportive communication categories presented below. Behavior which a listener perceives as possessing any of the characteristics listed in the left-hand column arouses defensiveness, whereas that which he interprets as having any of the qualities designated as supportive reduces defensive feelings. The degree to which these reactions occur depends upon the person’s level of defensiveness and the general climate in the group at the time.

Table 8.2 Communication in Defensive vs. Supportive Climates.

| Defensive Climates | Supportive Climates |

|---|---|

| 1. Evaluation | 1. Description |

| 2. Control | 2. Collaboration/Problem Orientation |

| 3. Strategy | 3. Spontaneity |

| 4. Neutrality | 4. Empathy |

| 5. Superiority | 5. Equality |

| 6. Certainty | 6. Provisionalism |

| Source: Problem Solving in Teams and Groups by Cameron W. Piercy, CC BY 4.0. | |

Evaluation and Description

Speech or other behavior which appears evaluative increases defensiveness. If by expression, manner of speech, tone of voice, or verbal content the sender seems to be evaluating or judging the listener, the receiver goes on guard. Of course, other factors may inhibit the reaction. If the listener thought that the speaker regarded them as an equal and was being open and spontaneous, for example, the evaluativeness in a message would be neutralized and perhaps not even perceived. This same principle applies equally to the other five categories of potentially defense-producing climates. These six sets are interactive.

Because our attitudes toward other persons are frequently, and often necessarily, evaluative, expressions that the defensive person will regard as nonjudgmental are hard to frame. Even the simplest question usually conveys the answer that the sender wishes or implies the response that would fit into their value system.

Anyone who has attempted to train professionals to use information-seeking speech with neutral affect appreciates how difficult it is to teach a person to say even the simple “who did that?” without being seen as accusing. Speech is so frequently judgmental that there is a reality base for the defensive interpretations which are so common.

When insecure, group members are particularly likely to place blame, to see others as fitting into categories of good or bad, to make moral judgments of their colleagues, and to question the value, motive, and affect loadings of the speech which they hear. Since value loadings imply a judgment of others, a belief that the standards of the speaker differ from their own causes the listener to become defensive.

Descriptive speech, in contrast to that which is evaluative, tends to arouse a minimum of uneasiness. Speech acts which the listener perceives as genuine requests for information or as material with neutral loadings are descriptive. Specifically, the presentation of feelings, events, perceptions, or processes which do not ask or imply that the receiver change behavior or attitude is minimally defense producing.

Table 8.3 Evaluation and Description Examples

| Defensive | Supportive |

|---|---|

| Evaluation | Description |

| Vague, abstract, blaming, inflammatory, and judgmental language that indicates lack of regard for other. "You" statements. | Neutral, factual, concrete, precise, descriptions of what something looks or sounds like, and of your own reactions to it. Ownership of thoughts, feelings, and observations. "I" language. No. Judgment(s) |

| Examples of Messages and Behaviors | |

| "You're such a slob! sheesh!" [eye role] | "I get frustrated when I see your socks on the floor" |

| Recipient's Potential Perception | |

| Recipient may feel attacked, judged, disrespected, and/or defensive in addition to possible confusion over what the complaint is specifically addressing. | Recipient has clarity about what's specifically bothering the other and why. They may not like something negative being pointed out, but they may not feel as judged, attacked, or put down as with the opposing example. |

| Source: "Frameworks for Identifying Types of Climate Messages" in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook by Pamela J. Gerber and Heidi Murphy, CC BY-SA 3.0. | |

Control and Problem Orientation

Speech that is used to control the listener evokes resistance. In most of our social interactions, someone is trying to do something to someone else—to change an attitude, to influence behavior, or to restrict the field of activity. The degree to which attempts to control produce defensiveness depends upon the openness of the effort, for a suspicion that hidden motives exist heightens resistance. For this reason, attempts of non-directive therapists and progressive educators to refrain from imposing a set of values, a point of view, or a problem solution upon the receivers meet with many barriers. Since the norm is control, non-controllers must earn the perception that their efforts have no hidden motives. A bombardment of persuasive “messages” in the fields of politics, education, special causes, advertising, religion, medicine, industrial relations, and guidance has bred cynical and paranoid responses in listeners.

Implicit in all attempts to alter another person is the assumption by the change agent that the person to be altered is inadequate. That the speaker secretly views the listener as ignorant, unable to make their own decisions, uninformed, immature, unwise, or possessed of wrong or inadequate attitudes is a subconscious perception that gives the latter a valid base for defensive reactions. A problem orientation looks to work collaboratively with the other party and find a solution that works for everyone.

Table 8.4 Control and Problem Orientation Examples

| Defensive | Supportive |

|---|---|

| Control | Problem Orientation |

| Speaker forces solutions with little regard for receiver's needs or interests. Messages seems to suggest that speakers knows better than listener, and/or that listener is not capable of finding solution. | Focus is on finding a win-win solution that meets the needs of all parties involved. Conveys respect for the other person. Makes decisions "with" rather than "for." Asks rather than tells. |

| Examples of Messages and Behaviors | |

| "No! You do it this way!" | "Since you actually work the floor, what are your thoughts about the best way to set this up?" |

| Recipient's Potential Perception | |

| Recipient may feel controlled, disrespected, or that their expertise/effort isnt acknowledged or respected. They may feel hostile towards the speaker and competitive rather than collaborative. | Recipient feels needs and wants are seen, respected, and honored. They will likely want to work collaboratively with the other person. |

| Source: "Frameworks for Identifying Types of Climate Messages" in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook by Pamela J. Gerber and Heidi Murphy, CC BY-SA 3.0. | |

Strategy and Spontaneity

When the sender is perceived as engaged in a stratagem involving ambiguous and multiple motivations, the receiver becomes defensive. No one wishes to be a guinea pig, a role player, or an impressed actor, and no one likes to be the victim of some hidden motivation. That which is concealed, also, may appear larger than it really is with the degree of defensiveness of the listener determining the perceived size of the element. Group members who are seen as “taking a role,” as feigning emotion, as toying with their colleagues, as withholding information, or as having special sources of data are especially resented.

A large part of the adverse reaction to much of the so-called human relations training is a feeling against what are perceived as gimmicks and tricks to fool or to “involve” people, to make a person think they are making their own decision, or to make the listener feel that the sender is genuinely interested in them as a person. Particularly violent reactions occur when it appears that someone is trying to make a stratagem appear spontaneous. One person reported a group member who incurred resentment by habitually using the gimmick of “spontaneously” looking at his watch and saying “my gosh, look at the time—I must run to an appointment.” The belief was that this person would create less irritation by honestly asking to be excused.

The aversion to deceit may account for one’s resistance to politicians who are suspected of behind-the-scenes planning to get one’s vote, to psychologists whose listening apparently is motivated by more than the manifest or content-level interest in one’s behavior, or the sophisticated, smooth, or clever person whose one-upmanship is marked with guile. In training groups, the role-flexible person frequently is resented because their changes in behavior are perceived as strategic maneuvers.

In contrast, behavior that appears to be spontaneous and free of deception is defense reductive. If the communicator is seen as having a clean id, as having uncomplicated motivations, as being straightforward and honest, as behaving spontaneously in response to the situation, he or she is likely to arouse minimal defensiveness.

Table 8.5 Strategy and Spontaneity Examples

| Defensive | Supportive |

|---|---|

| Strategy | Spontaneity |

| Dishonesty, manipulation, hidden agendas, passive-aggressiveness, guilt-making, score-keeping, tit-for-tat. | Honesty, respect, directness, openness. |

| Examples of Messages and Behaviors | |

| &$#@! Can't you EVER do what you promised?! I've been watching you do this all week and I'm fed up! [after observing from a silent pedestal and keeping score all week.] | "Honey, please wake up and let the dogs out." |

| Recipient's Potential Perception | |

| Recipient may feel attacked, judged, and controlled. They may feel distrustful or confused as to why the message was held back so long and not addressed. | Recipient may feel annoyed but appreciative that no judgment, extraneous complaints, or appeals to guilt were thrown in with the main point. |

| Source: "Frameworks for Identifying Types of Climate Messages" in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook by Pamela J. Gerber and Heidi Murphy, CC BY-SA 3.0. | |

Superiority and Equality

When a person communicates to another that he or she feels superior in position, power, wealth, intellectual ability, physical characteristics, or other ways, she or he arouses defensiveness. Here, as with other sources of disturbance, whatever arouses feelings of inadequacy causes the listener to center upon the affect loading of the statement rather than upon the cognitive elements. The receiver then reacts by not hearing the message, by forgetting it, by competing with the sender, or by becoming jealous of him or her.

The person who is perceived as feeling superior communicates that he or she is not willing to enter into a shared problem-solving relationship, that he or she probably does not desire feedback, that he or she does not require help, and/or that he or she will be likely to try to reduce the power, the status, or the worth of the receiver.

Many ways exist for creating the atmosphere that the sender feels himself or herself equal to the listener. Defenses are reduced when one perceives the sender as being willing to enter into participative planning with mutual trust and respect. Differences in talent, ability, worth, appearance, status, and power often exist, but the low defense communicator seems to attach little importance to these distinctions.

Table 8.6 Superiority and Equality Examples

| Defensive | Supportive |

|---|---|

| Superiority | Equality |

| Condescending and superior attitude, ridicule, eye-rolls, huffs and puffs, patronizing, one-up approach, conveys perceived "greater-than-you" status. | Sees equal worth in all human beings, recognizes that all people have strengths and weaknesses, respectful, honors and valuables people as capable beings. |

| Examples of Messages and Behaviors | |

| "Move over! I'll fix this! Sheesh!" [eye rolls] | "Hey, no worries. I struggled with this too when I first learned. I'll show you some strategies and you'll get it soon." |

| Recipient's Potential Perception | |

| Recipient may feel defensive, angry, or hurt. | Recipient may feel respected and thought of as capable. |

| Source: "Frameworks for Identifying Types of Climate Messages" in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook by Pamela J. Gerber and Heidi Murphy, CC BY-SA 3.0. | |

Certainty and Provisionalism

The effects of dogmatism in producing defensiveness are well known. Those who seem to know the answers, to require no additional data, and to regard themselves as teachers rather than as co-workers tend to put others on guard. Moreover, listeners often perceive manifest expressions of certainty as connoting inward feelings of inferiority. They see the dogmatic individual as needing to be right, as wanting to win an argument rather than solve a problem, and as seeing their ideas as truths to be defended. This kind of behavior often is associated with acts that others regarded as attempts to exercise control. People who are right seem to have a low tolerance for members who are “wrong”—i.e., who do not agree with the sender.

One reduces the defensiveness of the listener when one communicates that one is willing to experiment with one’s own behavior, attitudes, and ideas. The person who appears to be taking provisional attitudes, to be investigating issues rather than taking sides on them, to be problem-solving rather than doubting, and to be willing to experiment and explore tends to communicate that the listener may have some control over the shared quest or the investigation of the ideas. If a person is genuinely searching for information and data, he or she does not resent help or company along the way.

Table 8.7 Certainty and Provisionalism Examples

| Defensive | Supportive |

|---|---|

| Certainty | Provisionalism |

| It's "my way or the highway," already certain of being right, needs no additional input, one-track mind, lack or regard and respect for others' idea. | Acknowledged others' views, willingness to hear input, open-door policy, no corner on truth, open-mindedness, willing to change stance if reasonable. |

| Examples of Messages and Behaviors | |

| "I don't want to hear it. It's NOT going to work" | "I'm not familiar with that idea. Can you tell me more about it?" |

| Recipient's Potential Perception | |

| Recipient may feel devalued, defensive, or hostile. May feel unworthy or unaccepted. | Recipient may feel valued, recognized, capable, and worthy. |

| Source: "Frameworks for Identifying Types of Climate Messages" in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook by Pamela J. Gerber and Heidi Murphy, CC BY-SA 3.0. | |

Neutrality and Empathy

When neutrality in speech appears to the listener to indicate a lack of concern for their welfare, they becomes defensive. Group members usually desire to be perceived as valued persons, as individuals with special worth, and as objects of concern and affection. The clinical, detached, person-is-an-object-study attitude on the part of many psychologist-trainers is resented by group members. Speech with low affect that communicates little warmth or caring is in such contrast with the affect-laden speech in social situations that it sometimes communicates rejection.

Communication that conveys empathy for the feelings and respect for the worth of the listener, however, is particularly supportive and defense reductive. Reassurance results when a message indicates that the speaker identifies themself with the listener’s problems, shares their feelings, and accepts their emotional reactions at face value. Abortive efforts to deny the legitimacy of the receiver’s emotions by assuring the receiver that she need not feel badly, that she should not feel rejected, or that she is overly anxious, although often intended as support giving, may impress the listener as lack of acceptance. The combination of understanding and empathizing with the other person’s emotions with no accompanying effort to change him or her is supportive at a high level. The importance of gestural behavior cues in communicating empathy should be mentioned. Apparently spontaneous facial and bodily evidence of concern is often interpreted as especially valid evidence of deep-level acceptance.

Table 8.8 Neutrality and Empathy Examples

| Defensive | Supportive |

|---|---|

| Neutrality | Empathy |

| Indifference to a person's plight, impersonal response, lack of lack of concern and care, indicating the person or person's issue has little value. | Attempting to put yourself in the other's shoes, see what is seen, feel what is felt, acceptance, support and care of a person, feelings and issues. |

| Examples of Messages and Behaviors | |

| "Um. Yeah. It doesnt really matter what the reason is. The policy is the policy. No late papers." | "I'm so sorry for what you are going through. That's a tough situation. Let's talk about specific ways you might be able to keep up." |

| Recipient's Potential Perception | |

| Recipient may feel unworthy and inferior, that their needs aren't important, or are being ignored. They may feel a lack of connection and belonging. | Recipient may feel acknowledged, respected, and/or worthy of compassion. |

| Source: "Frameworks for Identifying Types of Climate Messages" in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook by Pamela J. Gerber and Heidi Murphy, CC BY-SA 3.0. | |

Let’s Focus: A Spotlight on Empathy

You may have heard empathy defined as the ability to (metaphorically) “put yourself in someone else’s shoes,” to feel what another may be feeling. This description is technically accurate on one level, but empathy is actually more complex. Our human capacity for empathy has three levels: cognitive, affective, and compassionate.

You may have heard empathy defined as the ability to (metaphorically) “put yourself in someone else’s shoes,” to feel what another may be feeling. This description is technically accurate on one level, but empathy is actually more complex. Our human capacity for empathy has three levels: cognitive, affective, and compassionate.

The first is cognitive and involves more thinking than feeling. A more appropriate metaphor for this level is “putting on someone else’s perception glasses,” to attempt to view a situation in the way someone else might view it. It requires thinking about someone else’s thinking, considering factors that make up someone’s unique perceptual schema, and trying to view a situation through that lens. For example, employees don’t always view things the way managers do. A good manager can see through employee glasses and anticipate how workplace actions, decisions, and/or messages may be interpreted.

The second level is affective, or emotional, and involves attempting to feel the emotions of others. The “shoes” metaphor fits best for this level. Attempting to truly feel what other humans feel requires envisioning exactly what they might be going through in their lives. Doing so effectively might even require “taking off your own shoes.” For example, to empathize with a complaining customer, we can temporarily put our own needs aside, and really picture what it would feel like to be the customer experiencing the problem situation. Your own need might be to take care of the complaint quickly so you can go to lunch. Yet, if it were you in the problem situation, you would likely want someone to be warm, attentive, and supportive, and take the time needed to solve the problem.

This level of empathy is often confused with sympathy, something with which you are probably already very familiar. The two are related but are not the same. Feeling sympathy means feeling bad for or sorry about something another person might be going through, but understanding and feeling it from your own perspective, through your own perception glasses, and in your own shoes. We all recognize that losing a pet is likely to be devastating for someone. We therefore feel sympathy for our friend because their dog died. However, feeling empathy requires making an effort to see the situation through their glasses and shoes. What this means is that we consider how they may see and feel the situation differently from us. For instance, we may have experienced many pet losses and even human losses in your life, so yet another pet loss may not feel that significant to us. But, if this is your friend’s first significant loss, they may likely feel more devastation than we would. We can respond more appropriately and with more warmth by letting go of our own perspective and attempting to see and feel the situation as they might. Another way to distinguish between sympathy and empathy is by seeing sympathy as “feeling for…” (as in feeling sorry for or feeling compassion for another person) and empathy as “feeling with…” as in actually feeling the emotions of another person.

The third level of empathy is the compassionate concern for the well-being of our fellow humans (Goleman, 2006). Feeling empathy at this level motivates us to act compassionately in the interest of others. Examples may include dropping off a casserole for a grieving friend, taking some of your coworker’s calls when they are especially busy or stressed, or organizing a neighborhood clean-up. With this level of empathy, we sense what people need and feel compelled to help. Most of us are usually able to empathize at this level with people who are important to us.

Strategies for Building Empathy

While empathy comes more naturally for some people than others, it is a skill that can be developed (Goleman, 2006) with a greater awareness of and attention to the perception process. Remember that perception is unique to each person. We all interpret and judge the world through our own set of perception glasses that are framed by factors such as upbringing, family background, ethnicity, age, attitude, knowledge of person and situation, past experiences, amount of exposure to others, social roles, etc.

Below addresses specific ways to build our empathy muscles. The strategies fall into two categories: adding information to the rims of our perception glasses and bringing attention to the perception process itself.

Add More Information to Our Perception Glasses

In order to add more information to our perception glasses, we need to find out what we can about a situation or person with whom we are seeking to understanding and empathize. We can do this by:

- Taking in information: When we observe, listen, question, perception check, paraphrase, pay attention to nonverbals and feelings, we take information in rather than putting information out (e.g., listening more and talking less).

- Broaden or narrow our perspective: Sometimes we feel stuck, allowing one interaction with one person to become all-consuming. If we remember how big the world is and how many people are dealing with similar situations right now, we gain perspective that helps us see the situation in a different way. On the other hand, sometimes we generalize too broadly, seeing an entire group of people in one way, or assuming all things are bad at our workplace. Focusing on one person or one situation a time is another way to helpfully shift perspectives.

- Imagine or seek stories and info (through books, films, articles, technology): We can learn and imagine what people’s lives are really like by reading, watching, or listening to the stories of others.

- Seek out actual experiences to help us understand what it’s like to be in others’ shoes: We can do something experiential like a ride-along with a police officer or spend a day on the streets to really try to feel what it’s like to be in a situation in which we are not familiar.

Bring Attention to the Perception Process.

Pull down our own perception glasses and try on a pair of someone else’s. Thinking about our thinking is a process called metacognition. By turning our attention toward the way we perceive information and how that perception makes us feel. What factors make up the rims of our glasses and how do these factors shape our perspectives, thoughts, feelings, and actions? Consider what makes another person unique, and what rim factors may influence the person’s perspectives and feelings. We should try to see the situation through those glasses, inferring how unique perceptual schemas might shape the others person’s emotions and actions too. Remember, though, we can never be certain how or why people do what they do. Only they know for sure. But communication can be more effective if we at least give some type of speculative forethought before we act or react. And when in doubt, we can always ask.

Adapted Works

The section Principles of Communication Climate is adapted from:

“Communication Climate” in Exploring Relationship Dynamics by Maricopa Community College District is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted, which is CC BY-SA 4.0.

The section Confirming and Disconfirming Messages is adapted from:

“Frameworks for Identifying Types of Climate Messages” in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook by Pamela J. Gerber and Heidi Murphy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, except where otherwise noted.

“Communication Climate” in Introduction to Public Communication (2nd edition) by Indiana State University and is is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The section Supportive and Defensive Communication Climates is adapted from:

“Culture, Climate, and Organizational Communication” in Organizational Communication by Julia Zink Ph.D is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The section Let’s Focus: A Spotlight on Empathy is adapted from:

“Empathy” in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook by Pamela J. Gerber and Heidi Murphy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, except where otherwise noted.

References

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press.

Gibb, J. R., (1961). Defensive communication. Journal of Communication, 11(3), 141–148.

Goleman, D. (2006). Social intelligence: The new science of human relationships. Bantam Books.

Lim, T.-S., & Bowers, J. W. (1991). Facework solidarity, approbation, and tact. Human Communication Research, 17(3), 415–450.

Nishina, A., Juvonen, J. & Witkow, M.R. (2005). Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will make me feel sick: The psychosocial, somatic, and scholastic consequences of peer harassment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 37-48.

Sofer, O. J. (2018). Say what you mean: A mindful approach to nonviolent communication. Shambhala Publications.

Ting-Toomey, S. (2005). Identity negotiation theory: Crossing cultural boundaries. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pp. 211-233). Sage Publications Ltd.

Wood, J. T. (1999). Interpersonal communication in everyday encounters (2nd ed.). Wadsworth.