6.3 Attributions

A major influence on how people behave is the way they interpret the events around them. People who feel they have control over what happens to them are more likely to accept responsibility for their actions than those who feel control of events is out of their hands. The cognitive process by which people interpret the reasons or causes for their behavior is described by attribution theory (Kelley, 1980; Fosterling, 1985; Weiner, 1980).

Specifically, “attribution theory concerns the process by which an individual interprets events as being caused by a particular part of a relatively stable environment” (Kelly, 1980, p. 193).

Attribution theory is based largely on the work of Fritz Heider. Heider argues that behavior is determined by a combination of internal forces (e.g., abilities or effort) and external forces (e.g., task difficulty or luck). Following the cognitive approach of Lewin and Tolman, he emphasizes that it is perceived determinants, rather than actual ones, that influence behavior. Hence, if employees perceive that their success is a function of their own abilities and efforts, they can be expected to behave differently than they would if they believed job success was due to chance.

The Attribution Process

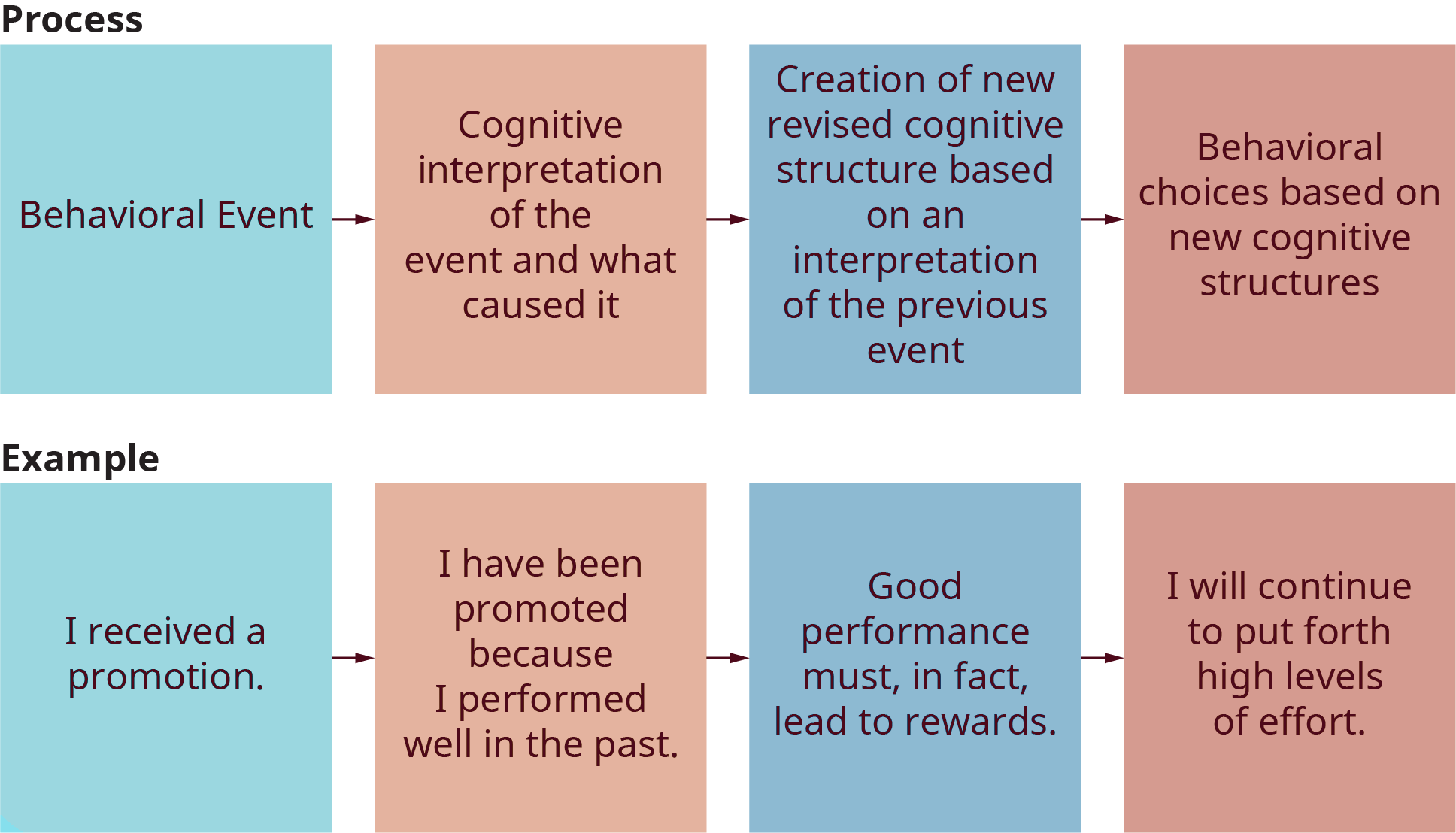

The underlying assumption of attribution theory is that people are motivated to understand their environment and the causes of particular events. If individuals can understand these causes, they will then be in a better position to influence or control the sequence of future events. This process is diagrammed in Figure 6.2. Specifically, attribution theory suggests that particular behavioral events (e.g., the receipt of a promotion) are analyzed by individuals to determine their causes. This process may lead to the conclusion that the promotion resulted from the individual’s own effort or, alternatively, from some other cause, such as luck.

Based on such cognitive interpretations of events, individuals revise their cognitive structures and rethink their assumptions about causal relationships. For instance, an individual may infer that performance does indeed lead to promotion. Based on this new structure, the individual makes choices about future behavior. In some cases, the individual may decide to continue exerting high levels of effort in the hope that it will lead to further promotions. On the other hand, if an individual concludes that the promotion resulted primarily from chance and was largely unrelated to performance, a different cognitive structure might be created, and there might be little reason to continue exerting high levels of effort. In other words, the way in which we perceive and interpret events around us significantly affects our future behaviors.

Internal and External Causes of Behavior

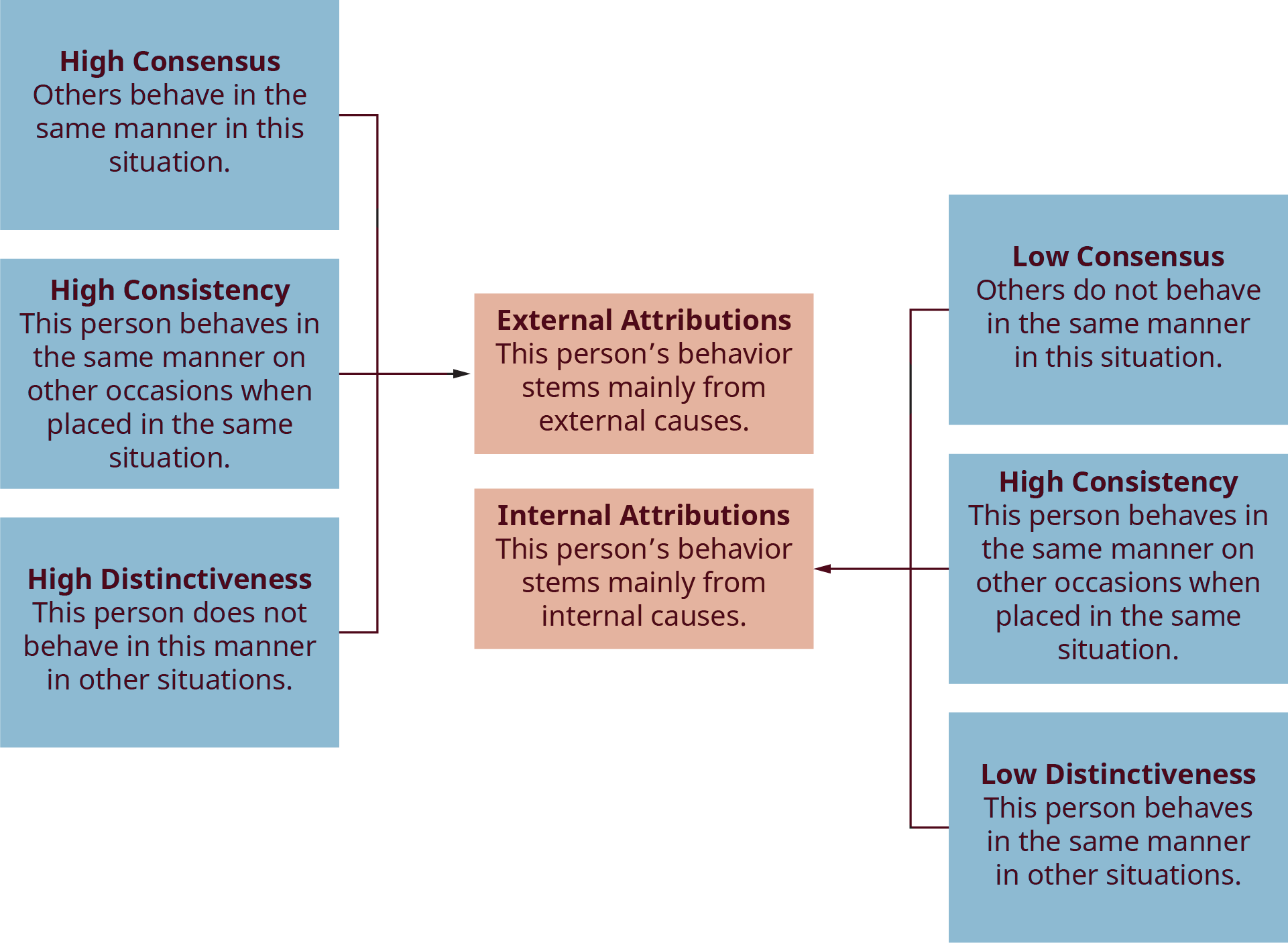

Building upon the work of Heider, Harold Kelley attempted to identify the major antecedents of internal and external attributions. He examined how people determine—or, rather, how they actually perceive—whether the behavior of another person results from internal or external causes. Internal causes include ability and effort, whereas external causes include luck and task ease or difficulty. Kelley’s conclusion, illustrated in Figure 6.6, is that people actually focus on three factors when making causal attributions:

Consensus

The first factor is consensus – the extent to which you believe that the person being observed is behaving in a manner that is consistent with the behavior of his or her peers. High consensus exists when the person’s actions reflect or are similar to the actions of the group; low consensus exists when the person’s actions do not.

Consistency

The second factor influencing whether attributions are internal or external is the consistency of the behaviour. That is to say, the extent to which you believe that the person being observed behaves consistently—in a similar fashion—when confronted on other occasions with the same or similar situations. High consistency exists when the person repeatedly acts in the same way when faced with similar stimuli.

Distinctiveness

Distinctiveness is the extent to which you believe that the person being observed would behave consistently when faced with different situations. Low distinctiveness exists when the person acts in a similar manner in response to different stimuli; high distinctiveness exists when the person varies their response to different situations.

How do these three factors interact to influence whether one’s attributions are internal or external? As seen in Figure 6.2, under conditions of high consensus, high consistency, and high distinctiveness, we would expect the observer to make external attributions about the causes of behavior. That is, the person would attribute the behavior of the observed (say, winning a hockey tournament) to good fortune or some other external event. On the other hand, when consensus is low, consistency is high, and distinctiveness is low, we would expect the observer to attribute the observed behavior (winning the hockey tournament) to internal causes (the winner’s skill).

In other words, we tend to attribute the reasons behind the success or failure of others to either internal or external causes according to how we interpret the underlying forces associated with the others’ behavior. Consider the example of the first female sales manager in a firm to be promoted to an executive rank. How do you explain her promotion—luck and connections or ability and performance? To find out, follow the model. If she, as a sales representative, had sold more than her (male) counterparts (low consensus in behavior), consistently sold the primary product line in different sales territories (high consistency), and was also able to sell different product lines (low distinctiveness), we would more than likely attribute her promotion to her own abilities.

On the other hand, if her male counterparts were also good sales representatives (high consensus) and her sales record on secondary products was inconsistent (high distinctiveness), people would probably attribute her promotion to luck or connections, regardless of her sales performance on the primary product line (high consistency).

Attributional Bias

One final point should be made with respect to the attributional process. In making attributions concerning the causes of behavior, people tend to make certain errors of interpretation. Two such errors, or attribution biases, are the fundamental attribution error and self-serving bias.

The Fundamental Attribution Error

In most interactions, we are constantly running an attribution script in our minds, which essentially tries to come up with explanations for what is happening. Why did my neighbor slam the door when she saw me walking down the hall? Why is my partner being extra nice to me today? Why did my officemate miss our project team meeting this morning? In general, we seek to attribute the cause of others’ behaviors to internal or external factors. Attributions are important to consider in conflict situations because our reactions to others’ behaviors are strongly influenced by the explanations we reach about the causes of behaviours. One of the most common perceptual errors is the fundamental attribution error, which refers to our tendency to explain others’ behaviors using internal rather than external attributions (Sillars, 1980).

Imagine two coworkers, Gurpreet and Aria. One day, Aria gets frustrated and raises her voice to Gurpreet. Gurpreet may find that behavior more offensive if she attributes the cause of the blow up to Aria’s personality, since personality traits are usually fairly stable and difficult to control or change. Conversely, Gurpreet may be more forgiving if she attributes the cause of Aria’s behavior to situational factors beyond her control, since external factors are usually temporary. If she makes an internal attribution, Gurpreet may think, “Wow, this person is really aggressive?” If she makes an external attribution, she may think, “Aria has been under a lot of pressure to meet deadlines at work and hasn’t been getting much sleep. Once this project is over, I’m sure she’ll be more relaxed.” This process of attribution is ongoing, and, as with many aspects of perception, we are sometimes aware of the attributions we make, and sometimes they are automatic and/or unconscious. Attribution has received much scholarly attention because it is in this part of the perception process that some of the most common perceptual errors or biases occur.

Self-Serving Bias

Perceptual errors can also be biased, and in the case of the self-serving bias, the error works out in our favor. Just as we tend to attribute others’ behaviors to internal rather than external causes, we do the same for ourselves, especially when our behaviors have led to something successful or positive. When our behaviors lead to failure or something negative, we tend to attribute the cause to external factors. Thus the self-serving bias is a perceptual error through which we attribute the cause of our successes to internal personal factors while attributing our failures to external factors beyond our control. When we look at the fundamental attribution error and the self-serving bias together, we can see that we are likely to judge ourselves more favorably than another person, or at least less personally.

The professor-student relationship offers a good case example of how these concepts can play out. I have sometimes heard students who earned an unsatisfactory grade on an assignment attribute that grade to the strictness, unfairness, or incompetence of their professor. I have also heard professors attribute a poor grade to the student’s attitude or lack of effort. In both cases, the behavior is explained using an internal attribution and is an example of the fundamental attribution error. Students may further attribute their poor grade to their busy schedule or other external, situational factors rather than their lack of motivation, interest, or preparation (internal attributions). On the other hand, when students gets a good grade on a paper, they will likely attribute that cause to their intelligence or hard work rather than an easy assignment or an “easy grading” professor. Both of these examples illustrate the self-serving bias. These psychological processes have implications for our communication because when we attribute causality to another person’s personality, we tend to have a stronger emotional reaction and tend to assume that this personality characteristic is stable, which may lead us to avoid communication with the person or to react negatively. Now that you aware of these common errors, you can monitor them more and engage in perception checking, which we will learn more about later, to verify your attributions.

Adapted Works

“Communication and Perception” in a A Primer on Communication Studies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

“Interpreting the Causes of Behaviour” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

Forsterling, F. (1985). Attributional retraining: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 495–512.

Kelley, H. H. (1973). The process of causal attributions. American Psychologist, 107–128.

Sillars, A. L. (1980). Attributions and communication in roommate conflicts. Communication Monographs, 47(3), 183.

Weiner, B. (1980). Human motivation. Rinehart and Winston.