5.1 Interpersonal Relationships at Work

Although some careers require less interaction than others, all jobs require interpersonal communication skills. Televisions shows like The Office offer glimpses into the world of workplace relationships. These humorous examples often highlight the dysfunction that can occur within a workplace. Since many people spend as much time at work as they do with their family and friends, the workplace becomes a key site for relation development. In this section, we will discuss relationships between supervisors and subordinates and also among coworkers. We will also address consensual workplace romantic relationships between coworkers and sexual harassment.

In this section:

Supervisor-Subordinate Relationships

Given that most workplaces are based on hierarchy, it is not surprising that relationships between supervisors and their subordinates develop (Sias, 2009). The supervisor-subordinate relationships can be primarily based in mentoring, friendship, or romance and includes two people, one of whom has formal authority over the other. In any case, these relationships involve some communication challenges and rewards that are distinct from other workplace relationships.

Information exchange is an important part of any relationship, whether it is self-disclosure about personal issues or disclosing information about a workplace to a new employee. Supervisors are key providers of information, especially for newly hired employees who have to negotiate through much uncertainty as they are getting oriented. The role a supervisor plays in orienting a new employee is important, but it is not based on the same norm of reciprocity that many other relationships experience at their onset. On a first date, for example, people usually take turns communicating as they learn about each other. Supervisors, on the other hand, have information power because they possess information that the employees need to do their jobs. The imbalanced flow of communication in this instance is also evident in the supervisor’s role as evaluator.

Most supervisors are tasked with giving their employees formal and informal feedback on their job performance. In this role, positive feedback can motivate employees, but what happens when a supervisor has negative feedback? Research shows that supervisors are more likely to avoid giving negative feedback if possible, even though negative feedback has been shown to be more important than positive feedback for employee development. This can lead to strains in a relationship if behavior that is in need of correcting persists, potentially threatening the employer’s business and the employee’s job.

We’re all aware that some supervisors are better than others and may have even experienced working under good and bad bosses. So what do workers want in a supervisor? Research has shown that employees more positively evaluate supervisors when they are of the same gender and race (Sias, 2009). This isn’t surprising, given that we’ve already learned that attraction is often based on similarity. In terms of age, however, employees prefer their supervisors be older than them, which is likely explained by the notion that knowledge and wisdom come from experience built over time. Additionally, employees are more satisfied with supervisors who exhibit a more controlling personality than their own, likely because of the trust that develops when an employee can trust that their supervisor can handle his or her responsibilities. Obviously, if a supervisor becomes coercive or is an annoying micromanager, the controlling has gone too far. High-quality supervisor-subordinate relationships in a workplace reduce employee turnover and have an overall positive impact on the organizational climate (Sias, 2005). Another positive effect of high-quality supervisor-subordinate relationships is the possibility of mentoring.

The mentoring relationship can be influential in establishing or advancing a person’s career, and supervisors are often in a position to mentor select employees. In a mentoring relationship, one person functions as a guide, helping another navigate toward career goals (Sias, 2009). Through workplace programs or initiatives sponsored by professional organizations, some mentoring relationships are formalized. Informal mentoring relationships develop as shared interests or goals bring two people together. Unlike regular relationships between a supervisor and subordinate that focus on a specific job or tasks related to a job, the mentoring relationship is more extensive. In fact, if a mentoring relationship succeeds, it is likely that the two people will be separated as the mentee is promoted within the organization or accepts a more advanced job elsewhere—especially if the mentoring relationship was formalized. Mentoring relationships can continue in spite of geographic distance, as many mentoring tasks can be completed via electronic communication or through planned encounters at conferences or other professional gatherings. Supervisors aren’t the only source of mentors, however, as peer coworkers can also serve in this role.

Coworker Relationships

According to organizational workplace relationship expert Patricia Sias (2009), peer coworker relationships exist between individuals who exist at the same level within an organizational hierarchy and have no formal authority over each other. According to Sias, we engage in these coworker relationships because they provide us with mentoring, information, power, and support. Let’s look at all four of these reasons for workplace relationships further.

Sias’ Reasons for Coworker Relationships

Mentoring

First, our coworker relationships are a great source for mentoring within any organizational environment. It’s always good to have that person who is a peer that you can run to when you have a question or need advice. Because this person has no direct authority over you, you can informally interact with this person without fear of reproach if these relationships are healthy.

Sources of Information

Second, we use our peer coworker relationships as sources for information. One important caveat to all of this involves the quality of the information we are receiving. By information quality, Sias refers to the degree to which an individual perceives the information they are receiving as accurate, timely, and useful. Ever had that one friend who always has great news, that everyone else heard the previous week? Yeah, not all information sources provide you with quality information. As such, we need to establish a network of high-quality information sources if we are going to be successful within an organizational environment.

Issues of Power

Third, we engage in coworker relationships as an issue of power. Although two coworkers may exist in the same run within an organizational hierarchy, it’s important also to realize that there are informal sources of power as well. Recall from our previous chapter, power can be useful and helps us influence what goes on within our immediate environments. However, power can also be used to control and intimidate people, which is a huge problem in many organizations.

Social Support

The fourth reason we engage in peer coworker relationships is social support. For our purposes, let’s define social support as the perception and actuality that an individual receives assistance, care, and help from those people within their life. Even the best organization in the world can be trying at times. The best manager in the world will eventually get under your skin about something. We’re humans; we’re flawed. As such, no organization is perfect, so it’s always important to have those peer coworkers we can go to who are there for us. Even if you love your job, sometimes you need to vent about something that has occurred. For the most part, we don’t want a coworker to solve a problem; just wants someone to listen.

Other Characteristics of Coworker Relationships

In addition to these four reasons for workplace relationships discussed by Sias, Jessica Methot (2010) argued that three other features are important to understand coworker relationships: trust, relational maintenance, and ability to focus. Let’s talk about each of these characteristics.

Trust

Methot (2010) defines trust as “the willingness to be vulnerable to another party with the expectation that the other party will behave with the best interest of the focal individual” (p. 45). In essence, in the workplace, we eventually learn how to make ourselves vulnerable to our coworkers believing that our coworkers will do what’s in our best interests. Now, trust is an interesting and problematic concept because it’s both a function of workplace relationships but also an outcome. For coworker relationships to work or operate as they should, we need to be able to trust our coworkers. However, the more we get to know our coworkers and know they have our best interests at heart, then the more we will ultimately trust our coworkers. Trust develops over time and is not something that is not just a bipolar concept of trust or doesn’t trust. Instead, there are various degrees of trust in the workplace. At first, you may trust your coworkers just enough to tell them surface level things about yourself (e.g., where you went to college, major, hometown, etc.), but over time, as we’ve discussed before in this book, we start to self-disclose as deeper levels as our trust increases. Now, most coworker relationships will never be intimate relationships or even actual friendships, but we can learn to trust our coworkers within the confines of our jobs.

Relational Maintenance

Kathryn Dindia and Daniel J. Canary (1993) wrote that definitions of the term “relational maintenance” could be broken down into four basic types:

- To keep a relationship in existence;

- To keep a relationship in a specified state or condition;

- To keep a relationship in a satisfactory condition; and

- To keep a relationship in repair.

Mithas argues that relational maintenance is difficult task in any context. Still, coworker relationships can have a range of negative outcomes if organizational members have difficulty maintaining their relationships with each other. For this reason, Mithas defines maintenance difficulty as “the degree of difficulty individuals experience in interpersonal relationships due to misunderstandings, incompatibility of goals, and the time and effort necessary to cope with disagreements” (Merthot, 2010, p. 49). Imagine you have two coworkers who tend to behave in an inappropriate fashion nonverbally. Maybe he sits there and rolls his eyes at everything his coworker says, or perhaps she uses exaggerated facial expressions to mock her coworker when he’s talking.

Having these types of coworkers will cause us (as a third party witnessing these problems) to spend more time trying to maintain relationships with both of them. On the flip side, the relationship between our two coworkers will take even more maintenance to get them to a point where they can just be collegial in the same room with each other. The more time we have to spend trying to decrease tension or resolve interpersonal conflicts in the workplace, the less time we will ultimately have on our actual jobs. Eventually, this can leave you feeling exhausted feeling and emotionally drained as though you just don’t have anything else to give. When this happens, we call this having inadequate resources to meet work demands.

All of us will eventually hit a wall when it comes to our psychological and emotional resources. When we do hit that wall, our ability to perform job tasks will decrease. As such, it’s essential that we strive to maintain healthy relationships with our coworkers ourselves, but foster an environment that encourages our coworkers to maintain healthy relationships with each other. However, it’s important to note that some people will simply never play well in the sandbox others. Some coworker relationships can become so toxic that minimizing contact and interaction can be the best solution to avoid draining your psychological and emotional resources.

Ability to Focus

Have you ever found your mind wandering while you are trying to work? One of the most important things when it comes to getting our work done is having the ability to focus. Within an organizational context, Methot (2010) defines ability to focus as “the ability to pay attention to value-producing activities without being concerned with extraneous issues such as off-task thoughts or distractions” (p. 47). When individuals have healthy relationships with their coworkers, they are more easily able to focus their attention on the work at hand. On the other hand, if your coworkers always play politics, stabbing each other in the back, gossiping, and engaging in numerous other counterproductive workplace (or deviant workplace) behaviors, then it’s going to be a lot harder for you to focus on your job.

Types of Coworker Relationships

Relationships with coworkers in a workplace can range from someone you say hello to almost daily without knowing their name, to an acquaintance in another department, to your best friend that you go on vacations with. We’ve already learned that proximity plays an important role in determining our relationships, and most of us will spend much of our time at work in proximity to and sharing tasks with particular people. However, we do not become friends with all our coworkers.

As with other relationships, perceived similarity and self-disclosure play important roles in workplace relationship formation. Most coworkers are already in close proximity, but they may break down into smaller subgroups based on department, age, or even whether or not they are partnered or have children (Sias, 2005). As individuals form relationships that extend beyond being acquaintances at work, they become peer coworkers. A peer coworker relationship refers to a workplace relationship between two people who have no formal authority over the other and are interdependent in some way. This is the most common type of interpersonal workplace relationship, given that most of us have many people we would consider peer coworkers and only one supervisor (Sias, 2005).

Even though we might not have a choice about whom we work with, we do choose who our friends at work will be. Coworker relationships move from strangers to friends much like other friendships. Perceived similarity may lead to more communication about workplace issues, which may lead to self-disclosure about non-work-related topics, moving a dyad from acquaintances to friends. Coworker friendships may then become closer as a result of personal or professional problems. For example, talking about family or romantic troubles with a coworker may lead to increased closeness as self-disclosure becomes deeper and more personal. Increased time together outside of work may also strengthen a workplace friendship (Sias & Cahill, 1998). Interestingly, research has shown that close friendships are more likely to develop among coworkers when they perceive their supervisor to be unfair or unsupportive. In short, a bad boss apparently leads people to establish closer friendships with coworkers, perhaps as a way to get the functional and relational support they are missing from their supervisor.

Friendships between peer coworkers have many benefits, including making a workplace more intrinsically rewarding, helping manage job-related stress, and reducing employee turnover. Peer friendships may also supplement or take the place of more formal mentoring relationships (Sias & Cahill, 1998). Coworker friendships also serve communicative functions, creating an information chain, as each person can convey information they know about what’s going on in different areas of an organization and let each other know about opportunities for promotion or who to avoid. Friendships across departmental boundaries in particular have been shown to help an organization adapt to changing contexts. Workplace friendships may also have negative effects. Obviously information chains can be used for workplace gossip, which can be unproductive. Additionally, if a close friendship at work leads someone to continue to stay in a job that they don’t like for the sake of the friendship, then the friendship is not serving the interests of either person or the organization. Although this section has focused on peer coworker friendships, some friendships have the potential to develop into workplace romances.

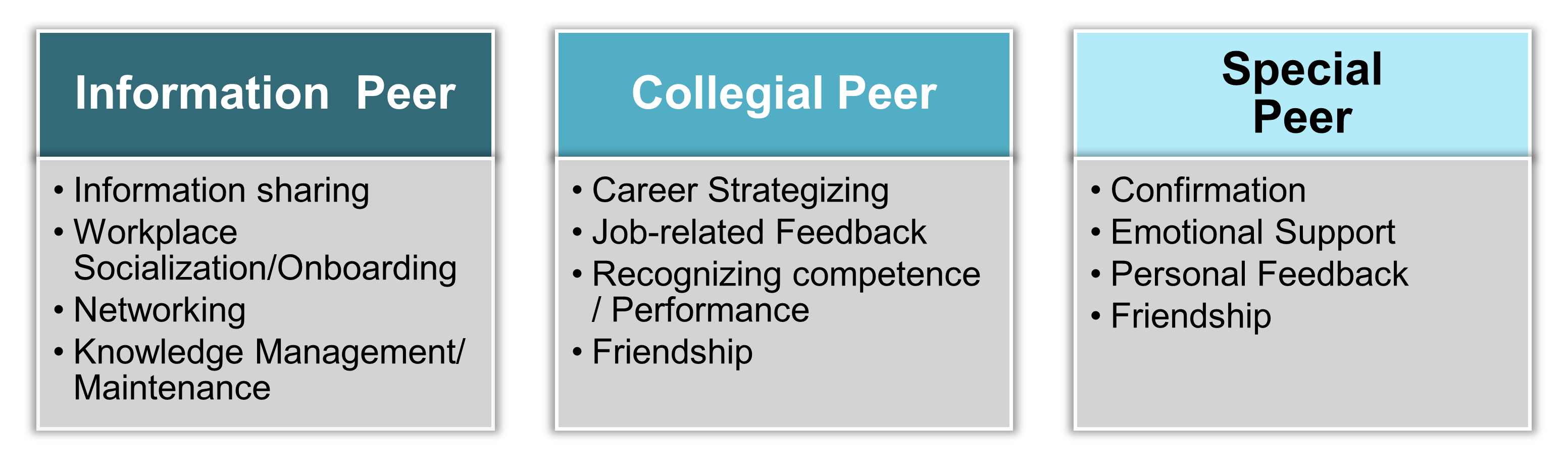

Now that we’ve looked at some of the characteristics of coworker relationships, let’s talk about the three different types of coworkers research has categorized. Kram and Isabelle (1985) found that there are essentially three different types of coworker relationships in the workplace: information peer, collegial peer, and special peer. Figure 5.1 illustrates the basic things we get from each of these different types of peer relationships.

Information Peers

Information peers are so-called because we rely on these individuals for information about job tasks and the organization itself. As you can see from Figure 5.1 there are four basic types of activities we engage information peers for information sharing, workplace socialization/onboarding, networking, and knowledge management/maintenance.

Information Sharing

First, we share information with our information peers. Of course, this information is task-focused, so the information is designed to help us complete our job better.

Workplace Socialization and Onboarding

Second, information peers are vital during workplace socialization or onboarding. Recall from our discussion on organizational culture, workplace socialization can be defined as the process by which new organizational members learn the rules (e.g., explicit policies, explicit procedures, etc.), norms (e.g., when you go on break, how to act at work, who to eat with, who not to eat with, etc.), and culture (e.g., innovation, risk-taking, team orientation, competitiveness, etc.) of an organization. Onboarding is the formal process of socialization when an organization helps new members get acquainted with the organization, its members, its customers, and its products/services.

Networking

>Third, information peers help us network within our organization or a larger field. Half of being successful in any organization involves getting to know the key players within the organization. Our information peers will already have existing relationships with these key players, so they can help make introductions. Furthermore, some of our peers may connect with others in the field (outside the organization), so they could help you meet other professionals as well.

Knowledge Management/Maintenance

Lastly, information peers help us manage and maintain knowledge. During the early parts of workplace socialization, our information peers will help us weed through all of the noise and focus on the knowledge that is important for us to do our jobs. As we become more involved in an organization, we can still use these information peers to help us acquire new knowledge or update existing knowledge. When we talk about knowledge, we generally talk about two different types: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge is information that is kept in some retrievable format. For example, you’ll need to find previously written reports or a list of customers’ names and addresses. These are examples of the types of information that physically (or electronically) may exist within the organization. Tacit knowledge, on the other hand, is the knowledge that’s difficult to capture permanently (e.g., write down, visualize, or permanently transfer from one person to another) because it’s garnered from personal experience and contexts. Informational peers who have been in an organization for a long time will have a lot of tacit knowledge. They may have an unwritten history of why policies and procedures are the way they are now, or they may know how to “read” certain clients because they’ve spent decades building relationships. For obvious reasons, it’s much easier to pass on explicit knowledge than implicit knowledge.

Collegial Peers

The second class of relationships we’ll have in the workplace are collegial peers or relationships that have moderate levels of trust and self-disclosure and is different from information peers because of the more openness that is shared between two individuals. Collegial peers may not be your best friends, but they are people that you enjoy working with. Some of the hallmarks of collegial peers include career strategizing, job-related feedback, recognizing competence/performance, friendship.

Career Strategizing

First, collegial peers help us with career strategizing. Career strategizing is the process of creating a plan of action for one’s career path and trajectory. First, notice that career strategizing is a process, so it’s marked by gradual changes that help you lead to your ultimate result. Career strategizing isn’t something that happens once, and we stay on that path for the rest of our lives. Often or intended career paths take twists and turns we never expected nor predicted. However, our collegial peers are often great resources for helping us think through this process either within a specific organization or a larger field.

Job-Related Feedback

Second, collegial peers also provide us with job-related feedback. We often turn to those who are around us the most often to see how we are doing within an organization. Our collegial peers can provide us this necessary feedback to ensure we are doing our jobs to the utmost of our abilities and the expectations of the organization. Under this category, the focus is purely on how we are doing our jobs and how we can do our jobs better. We will talk more about giving and receiving feedback in future chapters of this book.

Recognizing Competence/Performance

Third, collegial peers are usually the first to recognize our competence in the workplace and recognize us for excellent performance. Generally speaking, our peers have more interactions with us on the day-to-day job than does middle or upper management, so they are often in the best position to recognize our competence in the workplace. Our competence in the workplace can involve having valued attitudes (e.g., liking hard work, having a positive attitude, working in a team, etc.), cognitive abilities (e.g., information about a field, technical knowledge, industry-specific knowledge, etc.), and skills (e.g., writing, speaking, computer, etc.) necessary to complete critical work-related tasks. Not only do our peers recognize our attitudes, cognitive abilities, and skills, they are also there to pat us on the backs and tell us we’ve done a great job when a task is complete.

Friendship

Lastly, collegial peers provide us a type of friendship in the workplace. They offer us a sense of camaraderie in the workplace. They also offer us someone we can both like and trust in the workplace. Now, it’s important to distinguish this level of friendships from other types of friendships we have in our lives. Collegial peers are not going to be your “best friends,” but they will offer you friendships within the workplace that make work more bearable and enjoyable. At the collegial level, you may not associate with these friends outside of work beyond workplace functions (e.g., sitting next to each other at meetings, having lunch together, finding projects to work on together, etc.). It’s also possible that a group of collegial peers will go to events outside the workplace as a group (e.g., going to happy hour, throwing a holiday party, attending a baseball game, etc.).

Special Peers

The final group of peers we work with are called special peers. Kram and Isabella (1985)note that special peer relationships “involves revealing central ambivalences and personal dilemmas in work and family realms. Pretense and formal roles are replaced by greater self-disclosure and self-expression” (p. 121) Special peer relationships are marked by confirmation, emotional support, personal feedback, and friendship.

Confirmation

First, special peers provide us with confirmation. When we are having one of our darkest days at work and are not sure we’re doing our jobs well, our special peers are there to let us know that we’re doing a good job. They approve of who we are and what we do. These are also the first people we go to when we do something well at work.

Emotional Support

Second, special peers provide us with emotional support in the workplace. Emotional support from special peers comes from their willingness to listen and offer helpful advice and encouragement. Kelly Zellars and Pamela Perrewé (2001) have noted there are four types of emotional social support we get from peers: positive, negative, non-job-related, and empathic communication. Positive emotional support is when you and a special peer talk about the positive sides to work. For example, you and a special peer could talk about the joys of working on a specific project. Negative emotional support, on the other hand, is when you and a special peer talk about the downsides to work. For example, maybe both of you talk about the problems working with a specific manager or coworker. The third form of emotional social support is non-job-related or talking about things that are happening in your personal lives outside of the workplace itself. These could be conversations about friends, family members, hobbies, etc. A good deal of the emotional social support we get from special peers has nothing to do with the workplace at all. The final type of emotional social support is empathic communication or conversations about one’s emotions or emotional state in the workplace. If you’re having a bad day, you can go to your special peer, and they will reassure you about the feelings you are experiencing. Another example is talking to your special peer after having a bad interaction with a customer that ended with the customer yelling at you for no reason. After the interaction, you seek out your special peer, and they will confirm your feelings and thoughts about the interaction.

Personal Feedback

Third, special peers will provide both reliable and candid feedback about you and your work performance. One of the nice things about building an intimate special peer relationship is that both of you will be honest with one another. There are times we need confirmation, but then there are times we need someone to be bluntly honest with us. We are more likely to feel criticized and hurt when blunt honesty comes from someone when we do not have a special peer relationship. Special peer relationships provide a safe space where we can openly listen to feedback even if we’re not thrilled to receive that feedback.

Friendship

Lastly, special peers also offer us a sense of deeper friendship in the workplace. You can almost think of special peers as your best friend(s) within the workplace. Most people will only have one or maybe two people they consider a special peer in the workplace. You may be friendly with a lot of your peers (i.g., collegial peers), but having that special peer relationship is deeper and more meaningful.

A Further Look at Workplace Friendships

At some point, a peer coworker relationship may, or may not, evolve into a workplace friendship. According to Patricia Sias, there are two key hallmarks of a workplace friendship: voluntariness and personalistic focus. First, workplace friendships are voluntary. Someone can assign you a mentor or a mentee, but that person cannot make you form a friendship with that person. Most of the people you work with will not be your friends. You can have amazing working relationships with your coworkers, but you may only develop a small handful of workplace friendships. Second, workplace friendships have a personalistic focus. Instead of just viewing this individual as a coworker, we see this person as someone who is a whole individual who is a friend. According to research, workplace friendships are marked by higher levels of intimacy, frankness, and depth than those who are peer coworkers (Sias, & Cahill, 1998).

Friendship Development in the Workplace

According to Patricia Sias and Daniel Cahill (1998), workplace friendships are developed by a series of influencing factors: individual/personal factors, contextual factors, and communication changes. First, some friendships develop because we are drawn to the other person. Maybe you’re drawn to a person in a meeting because she has a sense of humor that is similar to yours, or maybe you find that another coworker’s attitude towards the organization is exactly like yours. Whatever the reason we have, we are often drawn to people that are like us. For this reason, we are often drawn to people who resemble ourselves demographically (e.g., age, sex, race, religion, etc.).

A second reason we develop relationships in the workplace is because of a variety of different contextual factors. Maybe your office is right next to someone else’s office, so you develop a friendship because you’re next to each other all the time. Perhaps you develop friendships because you’re on the same committee or put on the same work project with another person. In large organizations, we often end up making friends with people simply because we get to meet them. Depending on the size of your organization, you may end up meeting and interact with a tiny percentage of people, so you’re not likely to become friends with everyone in the organization equally. Other organizations provide a culture where friendships are approved of and valued. In the realm of workplace friendship research, two important factors have been noticed concerning contextual factors controlled by the organization: opportunity and prevalence (Nielsen et al., 2000). Friendship opportunity refers to the degree to which an organization promotes and enables workers to develop friendships within the organization. Does your organization have regular social gatherings for employees? Does your organization promote informal interaction among employees, or does it clamp down on coworker communication? Not surprisingly, individuals who work in organizations that allow for and help friendships tend to be satisfied, more motivated, and generally more committed to the organization itself.

Friendship prevalence, on the other hand, is less of an organizational culture and more the degree to which an individual feels that they have developed or can develop workplace friendships. You may have an organization that attempts to create an environment where people can make friends, but if you don’t think you can trust your coworkers, you’re not very likely to make workplace friends. Although the opportunity is important when seeing how an individual responds to the organization, friendship prevalence is probably the more important factor of the two. If I’m a highly communicative apprehensive employee, I may not end up making any friends at work, so I may see my workplace place as just a job without any commitment at all. When an individual isn’t committed to the workplace, they will probably start looking for another job (Nielsen et al., 2000).

Lastly, as friendships develop, our communication patterns within those relationships change. For example, when we move from being just an acquaintance to being a friend with a coworker, we are more likely to increase the amount of communication about non-work and personal topics. When we transition from friend to close friend, Sias and Cahill note that this change is marked by decreased caution and increased intimacy. Furthermore, this transition in friendship is characterized by an increase in discussing work-related problems. The final transition from a close friend to “almost best” friend. According to Sias and Cahill, “Because of the increasing amount of trust developed between the coworkers, they felt freer to share opinions and feelings, particularly their feelings about work frustrations. Their discussion about both work and personal issues became increasingly more detailed and intimate” (Sias & Cahill, 1998, p. 288).

Relationship Disengagement

Thus far, we’ve talked about workplace friendships as positive factors in the workplace, but any friendship can sour. Some friendships sour because one person moves into a position of authority of the other, so there is no longer perceived equality within the relationship. Some friendships devolve because of conflicting expectations of the relationship. Maybe one friend believes that giving him a heads up about insider information in the workplace is part of being a friend, and the other person sees it as a violation of trust given to her by her supervisors. When we have these conflicting ideas about what it means to “be a friend,” we can often see a schism that gets created. So, how does an individual get out of workplace friendships? Patricia Sias and Tarra Perry (2004) were the first researchers to discuss how colleagues disengage from relationships with their coworkers. Sias and Perry found three distinct tools that coworkers use: state-of-the-relationship talk, cost escalation, and depersonalization. Before explaining them, we should mention that people use all three and do not necessarily progress through the three in any order.

State-of-the-Relationship Talk

The first strategy people use when disengaging from workplace friendships involves state-of-the-relationship talk. State-of-the-relationship talk is exactly what it sounds like; you officially have a discussion that the friendship is ending. The goal of state-of-the-relationship talk is to engage the other person and inform them that ending the friendship is the best way to ensure that the two can continue a professional, functional relationship. Ideally, all workplace friendships could end in a situation where both parties agree that it’s in everyone’s best interest for the friendship to stop. Still, we all know this isn’t always the case, which is why the other two are often necessary.

Cost Escalation

The second strategy people use when ending a workplace friendship involves cost escalation. Cost escalation involves tactics that are designed to make the cost of maintaining the relationship higher than getting out of the relationship. For example, a coworker could start belittling a friend in public, making the friend the center of all jokes, or talking about the friend behind the friend’s back. All of these behaviors are designed to make the cost of the relationship too high for the other person.

Depersonalization

The final strategy involves depersonalization. Depersonalization can come in one of two basic forms. First, an individual can depersonalization a relationship by stopping all the interaction that is not task-focused. When you have to interact with the workplace friend, you keep the conversation purely business and do not allow for talk related to personal lives. The goal of this type of behavior is to alter the relationship from one of closeness to one of professional distance. The second way people can depersonalize a relationship is simply to avoid that person. If you know a workplace friend is going to be at a staff party, you purposefully don’t go. If you see the workplace friend coming down the hallway, you go in the opposite direction or duck inside a room before they can see you. Again, the purpose of this type of depersonalization is to put actual distance between you and the other person. According to Sias and Perry’s (2004) research, depersonalization tends to be the most commonly used tactic.

Romantic Relationships

Workplace romances involve two people who are emotionally and physically attracted to one another (Sias, 2009). We don’t have to look far to find evidence that this relationship type is the most controversial of all the workplace relationships (Boyd, 2010). So what makes these relationships so problematic?

Some research supports the claim that workplace romances are bad for business, while other research claims workplace romances enhance employee satisfaction and productivity. Despite this controversy, workplace romances are not rare or isolated, as research shows 75 to 85 percent of people are affected by a romantic relationship at work as a participant or observer (Sias, 2009). People who are opposed to workplace romances cite several common reasons. More so than friendships, workplace romances bring into the office emotions that have the potential to become intense. This doesn’t mesh well with a general belief that the workplace should not be an emotional space. Additionally, romance brings sexuality into workplaces that are supposed to be asexual, which also creates a gray area in which the line between sexual attraction and sexual harassment is blurred (Sias, 2009). People who support workplace relationships argue that companies shouldn’t have a say in the personal lives of their employees and cite research showing that workplace romances increase productivity. Obviously, this is not a debate that we can settle here. Instead, let’s examine some of the communicative elements that affect this relationship type.

Individuals may engage in workplace romances for many reasons, three of which are job motives, ego motives, and love motives (Sias, 2009). Job motives include gaining rewards such as power, money, or job security. Ego motives include the “thrill of the chase” and the self-esteem boost one may get. Love motives include the desire for genuine affection and companionship. Despite the motives, workplace romances impact coworkers, the individuals in the relationship, and workplace policies. Romances at work may fuel gossip, especially if the couple is trying to conceal their relationship. This could lead to hurt feelings, loss of trust, or even jealousy. If coworkers perceive the relationship is due to job motives, they may resent the appearance of favoritism and feel unfairly treated. The individuals in the relationship may experience positive effects such as increased satisfaction if they get to spend time together at work and may even be more productive. Romances between subordinates and supervisors are more likely to slow productivity. If a relationship begins to deteriorate, the individuals may experience more stress than other couples would, since they may be required to continue to work together daily.

Over the past couple decades, there has been a national discussion about whether or not organizations should have policies related to workplace relationships, and there are many different opinions. Company policies range from complete prohibition of romantic relationships, to policies that only specify supervisor-subordinate relationships as off-limits, to policies that don’t prohibit but discourage love affairs in the workplace (Sias, 2009). One trend that seeks to find middle ground is the “love contract” or “dating waiver” (Boyd, 2010). This requires individuals who are romantically involved to disclose their relationship to the company and sign a document saying that it is consensual and they will not engage in favoritism. Some businesses are taking another route and encouraging workplace romances. Southwest Airlines, for example, allows employees of any status to date each other and even allows their employees to ask passengers out on a date. Other companies like AT&T and Ben and Jerry’s have similar open policies (Boyd, 2010). Some organizations require a consensual romance agreement to be signed by two romantically–involved employees representing that their relationship is entirely consensual and acknowledging the employer’s anti-harassment policies and rules. Parties are also often reminded in these documents the standards for appropriate behavior (e.g., limiting displays of affection), conflict of interest, preferential treatment, etc that might arise as a result of the relationship. Finally, the document may also outline expectations for behaviour if the relationship ends.

Sexual Harassment

While we just discussed consensual romantic relationships in the workplace, it is also important to acknowledge the fact that many romantic advances that occur in the workplace are unsolicited and unwanted. It is important for everyone to be aware of what sexual harassment is, what types of behaviours that it entails, and what to do you if you are the subject of unwanted advances at work or if you witness an incidence of sexual harassment against another individual in your place of work.The Canada Labour Code’s definition of sexual harassment is quite broad, but oriented more toward the perception of the person offended than the intentions of the offender. Though there is nothing wrong with discrete flirtation between two consenting adults on break at work, a line is crossed as soon as one of them—or third-party observers—feels uncomfortable with actions or talk of sexual nature. According to Provision 241.1 of the Code,sexual harassment means any conduct, comment, gesture or contact of a sexual nature that is likely to cause offence or humiliation to any employee, or that might, on reasonable grounds, be perceived by that employee as placing a condition of a sexual nature on employment or on any opportunity for training or promotion. (Government of Canada, 1985, p. 214)The Code clarifies that all employees have a right to conduct their work without being harassed (241.2), but what does that look like in practice?

Let’s Focus: What Constitute Sexual harassments

For help with understanding what specific behaviours constitute sexual harassment, the City of Toronto’s Human Rights Office’s 2017 “Sexual Harassment in the Workplace” guide lists the following 21 examples of offenses that have had their day in court:

For help with understanding what specific behaviours constitute sexual harassment, the City of Toronto’s Human Rights Office’s 2017 “Sexual Harassment in the Workplace” guide lists the following 21 examples of offenses that have had their day in court:

-

Image: Fundamentals Of Business Communication by Venecia Williams and Jordan Smith. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0,. [Click to enlarge]. Making unnecessary physical contact, including unwanted touching (e.g., stroking hair, demanding hugs, or rubbing a person’s back)

- Invading personal space

- Using language that puts someone down because of their sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression

- Using sex-specific derogatory names, homophobic or transphobic epithets, slurs, or jokes

- Leering or inappropriate staring

- Gender related comments about a person’s physical characteristics or mannerisms, comments that police or reinforce traditional heterosexual gender norms

- Targeting someone for not following sex-role stereotypes (e.g., comments made to a female for being in a position of authority)

- Showing or sending pornography, sexual images, etc. (e.g., pinning up an image of a naked man in the bathroom)

- Making sexual jokes, including forwarding sexual jokes by email

- Rough or vulgar language related to gender (e.g., “locker-room talk”)

- Spreading sexual rumours, “outing” or threatening to out someone who is LGBTQ2S (e.g., sending an email to colleagues about an affair between a supervisor and another employee)

- Making suggestive or offensive comments about members of a specific gender

- Sexually propositioning a person

- Bragging about sexual prowess

- Asking questions about sexual preferences, fantasies, or activities

- Demanding dates or sexual favours

- Verbally abusing, threatening, or taunting someone based on gender

- Threatening to penalize or punish a person who refuses to comply with sexual advances

- Intrusive comments, questions or insults about a person’s body, physical characteristics, gender-related medical procedures, clothing, mannerisms, or other forms of gender expression

- Refusing to refer to a person by their self-identified name or proper personal pronoun, or requiring a person to prove their gender

- Circulating or posting of homophobic, transphobic, derogatory or offensive signs, caricatures, graffiti, pictures, or other materials

The guide explains that any such behaviours involving professional colleagues in the physical or online workspace, as well as offsite outside of normal hours (e.g., work parties or community events), should be reported without fear of reprisal (City of Toronto, 2017, pp. 2-3).

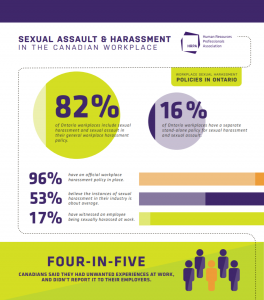

According to Doing Our Duty: Preventing Sexual Harassment in the Workplace by the Human Resources Professionals Association (HRPA, 2018), “sexual harassment in the workplace is an epidemic that has been allowed to persist” for too long (p. 5). In a survey of nearly a thousand HRPA members in Ontario, 43% of women said they’ve been sexually harassed in the workplace, and about four-fifths said they didn’t report it to their employers (p. 12). In a separate online survey of 2000 Canadians nationwide, 34% of women reported experiencing sexual harassment in the workplace and 12% of men, and nearly 40% of those say it involved someone who had a direct influence over their career success (Navigator, 2018, p. 5). These perceptions are completely out of step with what top executives believe, with 95% of 153 surveyed Canadian CEOs and CFOs confirming that sexual harassment is not a problem in their workplaces (Gandalf Group, 2017, p. 9). Clearly there are differences of opinion between those who experience sexual harassment on the floor and those in the executive suites who are responsible for the safety of their employees, and much of the confusion may have to do with how sexual harassment is defined.

How to Make Workplaces More Respectful

Though the Canada Labour Code places the responsibility of ensuring a harassment-free workplace squarely on the employer (Provision 247.3), all employees must do their part to uphold one another’s right to work free of harassment. At the very least, everyone should avoid any of the 21 specific examples of sexual harassment listed above, even in the context of lighthearted banter. Employees everywhere should be held to a higher standard, however, which the HRPA advocates in the following recommendations:

- All companies must have a stand-alone sexual harassment and assault policy, as required by the Labour Code.

- All employees must familiarize themselves with their company’s sexual harassment policy, which should include guidance on how to report instances of harassment.

- All companies must conduct training sessions on their sexual harassment policy, including instruction on what to do when harassed or witnessing harassment, and all employees must participate.

Of course, experiencing harassment places the victim in a difficult position with regard to their job security, as does witnessing it and the duty to report. The situation is even more complicated if the perpetrator has the power to promote, demote, or terminate the victim’s or witness’s employment. If you find yourself in such a situation, seeking the confidential advice of an ombudsperson or person in a similar counselling role should be your first recourse. Absent these internal protections, consider seeking legal counsel.

If you witness sexual or other types of harassment, what should you do? The following guide may help:

If you witness sexual or other types of harassment, what should you do? The following guide may help:

- If it’s safe for you to do so, try recording video the incident on your smartphone. The mere presence of the phone may act as a deterrent to further harassment. If not, however, a record of the incident will be valuable in the post-incident pursuit of justice.

- If you can play any additional role in stopping the harassment before it continues, try to get the attention of the person being harassed and ask them if they want support and what exactly you can do.

- If it’s welcome from the victim and safe for both you and them, try to place yourself between them and the attacker. If the victim is handling the attack in their own way, respect their choice.

- If the harassment continues, try to de-escalate the situation non-violently by explaining to the offender that the one being harassed has a right to work in peace. Only resort to violence if it’s defensive.

- After a safe resolution, follow up with the person being harassed about what you can do for them (American Friends Service Committee, 2016).

Of course, every harassment situation is different and requires quick-thinking action that maintains the safety of all involved. The important thing, however, is to be act as an ally to the person being harassed. The biggest takeaway from the development of the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements is that a workplace culture that permits sexual harassment will only end if we all do our part to ensure that offenses no longer go unreported and unpunished.

Case Study

Adapted Works

“Interpersonal Relationships at Work – Interpersonal Communication” in Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Relationships at Work” in Communication in the Real World by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Professionalism, Etiquette, and Ethical Behaviour” in Fundamentals of Business Education by Venecia Williams and Jordan Smith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Professionalism, Etiquette, and Ethical Behaviour” in Communication at Work by Jordan Smith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

American Friends Service Committee. (2016, December 2). Do’s and Don’ts for bystander intervention. https://www.afsc.org/resource/dos-and-donts-bystander-intervention

Boyd, C. (2010). The debate over the prohibition of romance in the workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 325.

City of Toronto. (2017, October). Sexual harassment in the workplace. https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/8eaa-workplace-sexual-harassment.pdf

Dindia, K., & Canary, D. J. (1993). Definitions and theoretical perspectives on maintaining relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10(2), 163-173. https://doi.org/10.1177/026540759301000201

Government of Canada. (1985). Canada labour code. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/L-2.pdf

HRPA. (2018). Sexual harassment infographic. https://www.hrpa.ca/Documents/Public/Thought-Leadership/Sexual-Assault-Harassment-Infographic.pdf

Kram, K. E., & Isabella, L. A. (1985). Mentoring alternatives: The role of peer relationships in career development. Academy of Management Journal, 28(1), 110–132. https://doi.org/10.5465/256064

Methot, J. R. (2010). The effects of instrumental, friendship, and multiplex network ties on job performance: A model of coworker relationships [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation]. University of Florida. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UFE0041583/00001

Navigator. (2018, March 7). Sexual harassment survey results. http://www.navltd.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Report-on-Publics-Perspective-of-Sexual-Harassment-in-the-Workplace.pdf

Nielsen, I. K., Jex, S. M., & Adams, G. A. (2000). Development and validation of scores on a two-dimensional workplace friendship scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60(4), 628-643. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131640021970655

Sias, P. M., & Cahill, D. J. (1998). From coworkers to friends: The development of peer friendships in the workplace. Western Journal of Communication, 62(3), 273–299.

Sias, P. M., (2005). Workplace relationship quality and employee information experiences. Communication Studies, 56(4), 377.

Sias, P. M. (2009). Organizing relationships: Traditional and emerging perspectives on workplace relationships. Sage.

Sias, P. M., & Perry, T. (2004). Disengaging from workplace relationships: A research note. Human Communication Research, 30(4), 589-602. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00746.x

Zellars, K. L., & Perrewé, P. L. (2001). Affective personality and the content of emotional social support: Coping in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.459