4.2 Politics and Influence

In this section:

Organizational Politics

Organizational politics are informal, unofficial, and sometimes behind-the-scenes efforts to sell ideas, influence an organization, increase power, or achieve other targeted objectives (Brandon & Seldman, 2004: Hochwarter et al., 2000). Politics has been around for millennia. Aristotle wrote that politics stems from a diversity of interests, and those competing interests must be resolved in some way. “Rational” decision making alone may not work when interests are fundamentally incongruent, so political behaviors and influence tactics arise.

Another definition of politics was offered by Lasswell (1936), who described it as who gets what, when, and how. Even from this simple definition, one can see that politics involves the resolution of differing preferences in conflicts over the allocation of scarce and valued resources. Politics represents one mechanism to solve allocation problems when other mechanisms, such as the introduction of new information or the use of a simple majority rule, fail to apply.

In comparing the concept of politics with the related concept of power, Pfeffer notes:

If power is a force, a store of potential influence through which events can be affected, politics involves those activities or behaviors through which power is developed and used in organizational settings. Power is a property of the system at rest; politics is the study of power in action. An individual, subunit or department may have power within an organizational context at some period of time; politics involves the exercise of power to get something accomplished, as well as those activities which are undertaken to expand the power already possessed or the scope over which it can be exercised.

In other words, from this definition it is clear that political behavior is activity that is initiated for the purpose of overcoming opposition or resistance. In the absence of opposition, there is no need for political activity. Moreover, it should be remembered that political activity need not necessarily be dysfunctional for organization-wide effectiveness. In fact, many managers often believe that their political actions on behalf of their own departments are actually in the best interests of the organization as a whole.

Finally, we should note that politics, like power, is not inherently bad. In many instances, the survival of the organization depends on the success of a department or coalition of departments challenging a traditional but outdated policy or objective. That is why an understanding of organizational politics, as well as power, is so essential for managers. As John Kotter (1985) wrote in Power and Influence, “Without political awareness and skill, we face the inevitable prospect of becoming immersed in bureaucratic infighting, parochial politics and destructive power struggles, which greatly retard organizational initiative, innovation, morale, and performance.”

In our discussion about power, we saw that power issues (and conflict) often arise around scarce resources. Organizations typically have limited resources that must be allocated in some way. Individuals and groups within the organization may disagree about how those resources should be allocated, so they may naturally seek to gain those resources for themselves or for their interest groups, which gives rise to organizational politics. Simply put, with organizational politics, individuals ally themselves with like-minded others in an attempt to win the scarce resources. They’ll engage in behavior typically seen in government organizations, such as bargaining, negotiating, alliance building, and resolving conflicting interests.

Politics are a part of organizational life, because organizations are made up of different interests that need to be aligned. In fact, 93% of managers surveyed reported that workplace politics exist in their organization, and 70% felt that in order to be successful, a person has to engage in politics (Gandaz & Murray, 1980). In the negative light, saying that someone is “political” generally stirs up images of backroom dealing, manipulation, or hidden agendas for personal gain. A person engaging in these types of political behaviors is said to be engaging in self-serving behavior that is not sanctioned by the organization (Ferris et al., 1996; Valle & Perrewe, 2000; Harris et al., 2005; Randall et al., 1999).

Examples of these self-serving behaviors include bypassing the chain of command to get approval for a special project, going through improper channels to obtain special favors, or lobbying high-level managers just before they make a promotion decision. These types of actions undermine fairness in the organization, because not everyone engages in politicking to meet their own objectives. Those who follow proper procedures often feel jealous and resentful because they perceive unfair distributions of the organization’s resources, including rewards and recognition (Parker et al., 1995).

Researchers have found that if employees think their organization is overly driven by politics, the employees are less committed to the organization (Maslyn & Fedor, 1998 Nye & Wit, 1993), have lower job satisfaction (Ferris et al., 1996; Hochwarter et al., 2010; Kacmar et al., 1999) perform worse on the job (Anderson, 1994), have higher levels of job anxiety (Ferris et al., 1996; Kacmar & Ferris, 1989), and have a higher incidence of depressed mood (Byrne et al., 2005).

The negative side of organizational politics is more likely to flare up in times of organizational change or when there are difficult decisions to be made and a scarcity of resources that breeds competition among organizational groups. To minimize overly political behavior, company leaders can provide equal access to information, model collaborative behavior, and demonstrate that political maneuvering will not be rewarded or tolerated. Furthermore, leaders should encourage managers throughout the organization to provide high levels of feedback to employees about their performance. High levels of feedback reduce the perception of organizational politics and improve employee morale and work performance (Rosen et al., 2006). Remember that politics can be a healthy way to get things done within organizations.

Intensity of Political Behavior

Contemporary organizations are highly political entities. Indeed, much of the goal-related effort produced by an organization is directly attributable to political processes. However, the intensity of political behavior varies, depending upon many factors. For example, in one study, managers were asked to rank several organizational decisions on the basis of the extent to which politics were involved (Ganz & Murray, 1980). Results showed that the most political decisions (in rank order) were those involving interdepartmental coordination, promotions and transfers, and the delegation of authority. Such decisions are typically characterized by an absence of established rules and procedures and a reliance on ambiguous and subjective criteria.

On the other hand, the managers in the study ranked as least political such decisions as personnel policies, hiring, and disciplinary procedures. These decisions are typically characterized by clearly established policies, procedures, and objective criteria.

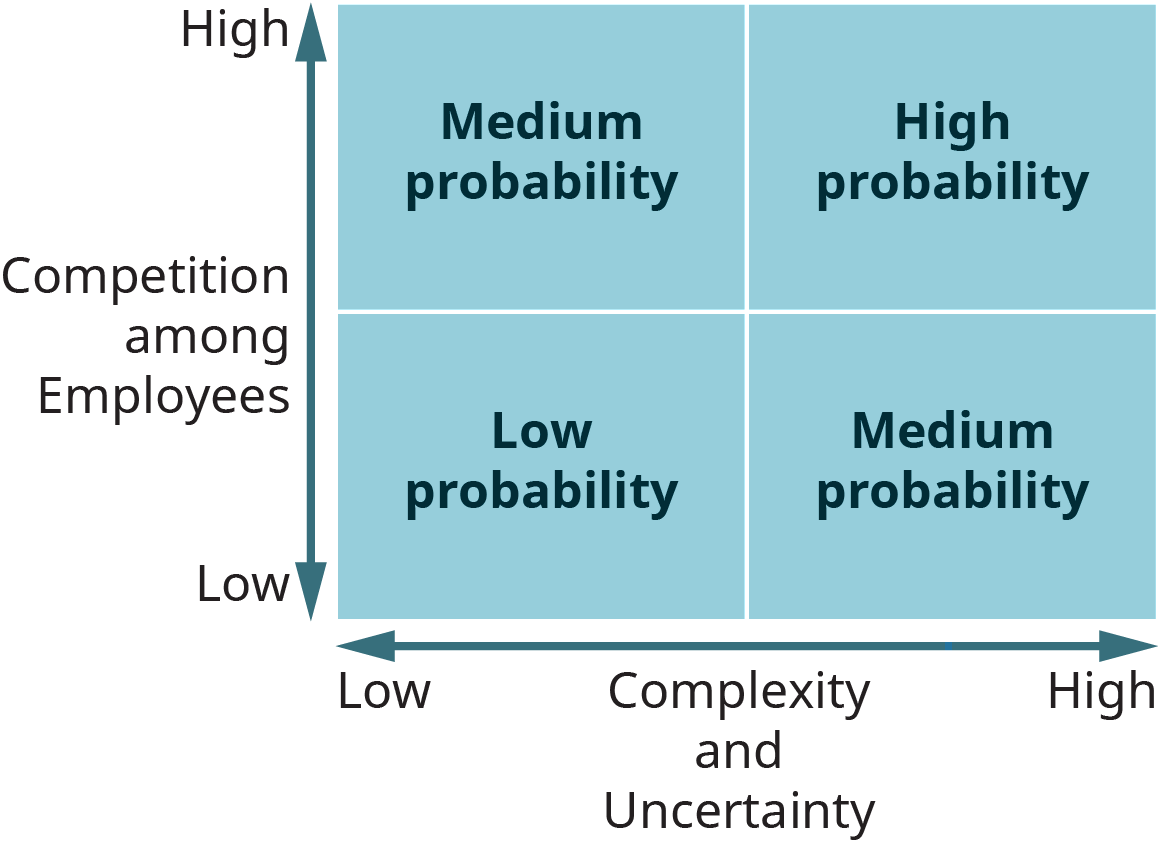

On the basis of findings such as these, it is possible to develop a typology of when political behavior would generally be greatest and least. This model is shown in Figure 4.3 below. As can be seen, we would expect the greatest amount of political activity in situations characterized by high uncertainty and complexity and high competition among employees or groups for scarce resources. The least politics would be expected under conditions of low uncertainty and complexity and little competition among employees over resources.

Reasons for Political Behaviour

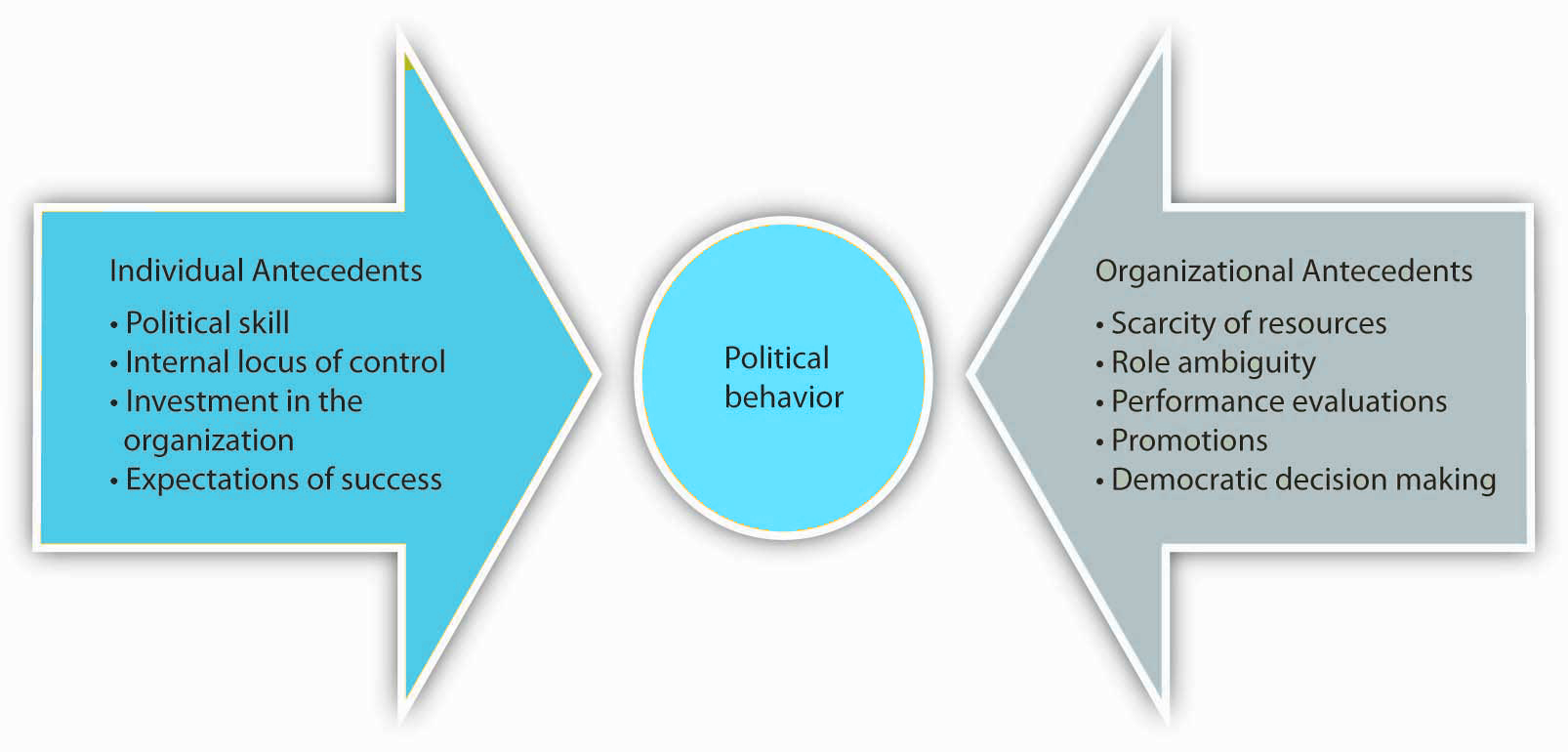

We can trace the source of political behaviour back to a number of ancedents. We will broadly define these as individual factors and organizational factors.

Individual Antecedents of Political Behaviour

Individual antecedents of political behaviour include political skills, locus of control, investment in the organization and expectation of success. Let’s talk about each.

Political Skill

Political skill refers to peoples’ interpersonal style, including their ability to relate well to others, self-monitor, alter their reactions depending upon the situation they are in, and inspire confidence and trust (Ferris et al., 2000). Researchers have found that individuals who are high on political skill are more effective at their jobs or at least in influencing their supervisors’ performance ratings of them (Ferris et al., 1994: Kilduff & Day, 1994).

Internal Locus of Control

Individuals who are high in internal locus of control believe that they can make a difference in organizational outcomes. They do not leave things to fate. Therefore, we would expect those high in internal locus of control to engage in more political behavior. Research shows that these individuals perceive politics around them to a greater degree (Valle & Perrewe, 2000).

Investment in the Organization

Investment in the organization is also related to political behavior. If a person is highly invested in an organization either financially or emotionally, they will be more likely to engage in political behavior because they care deeply about the fate of the organization.

Expectations of Success

Finally, expectations of success also matter. When a person expects that they will be successful in changing an outcome, they are more likely to engage in political behavior. Think about it: If you know there is no chance that you can influence an outcome, why would you spend your valuable time and resources working to effect change? You wouldn’t. Over time you’d learn to live with the outcomes rather than trying to change them (Bandura, 1996).

Organizational Antecedents

In additional to characteristics of an individual, we can also observe political behaviour that is rooted in the nature of the organization and its culture. Relevant factors include scarcity of resources, role ambiguity, performance evaluations, promotions, and democratic decision making.

Scarcity of Resources

Scarcity of resources breeds politics. When resources such as monetary incentives or promotions are limited, people see the organization as more political. When resources are are scarce and allocation decisions must be made. If resources were ample, there would be no need to use politics to claim one’s “share.”

Periods of organizational change also present opportunities and politics. Efforts to restructure a particular department, open a new division, introduce a new product line, and so forth, are invitations to all to join the political process as different factions and coalitions fight over territory and resources.

Ambiguity

Any type of ambiguity can relate to greater organizational politics. When the goals of a department or organization are ambiguous, more room is available for politics. As a result, members may pursue personal gain under the guise of pursuing organizational goals. For example, role ambiguity allows individuals to negotiate and redefine their roles. This freedom can become a political process. Research shows that when people do not feel clear about their job responsibilities, they perceive the organization as more political (Muhammad, 2007).

In general, political behavior is increased when the nature of the internal technology is nonroutine and when the external environment is dynamic and complex. Under these conditions, ambiguity and uncertainty are increased, thereby triggering political behavior by groups interested in pursuing certain courses of action.

Performance Evaluations

Ambiguity also exists around performance evaluations and promotions. These human resource practices can lead to greater political behavior, such as impression management, throughout the organization.

Democratic Decision-Making

As you might imagine, democratic decision-making leads to more political behavior. Since many people have a say in the process of making decisions, there are more people available to be influenced.

With respect to decision-making, non-programmed decisions can result in political behaviour. When decisions are not programmed, conditions surrounding the decision problem and the decision process are usually more ambiguous, which leaves room for political maneuvering. Programmed decisions, on the other hand, are typically specified in such detail that little room for maneuvering exists. Hence, we are likely to see more political behavior on major questions, such as long-range strategic planning decisions.

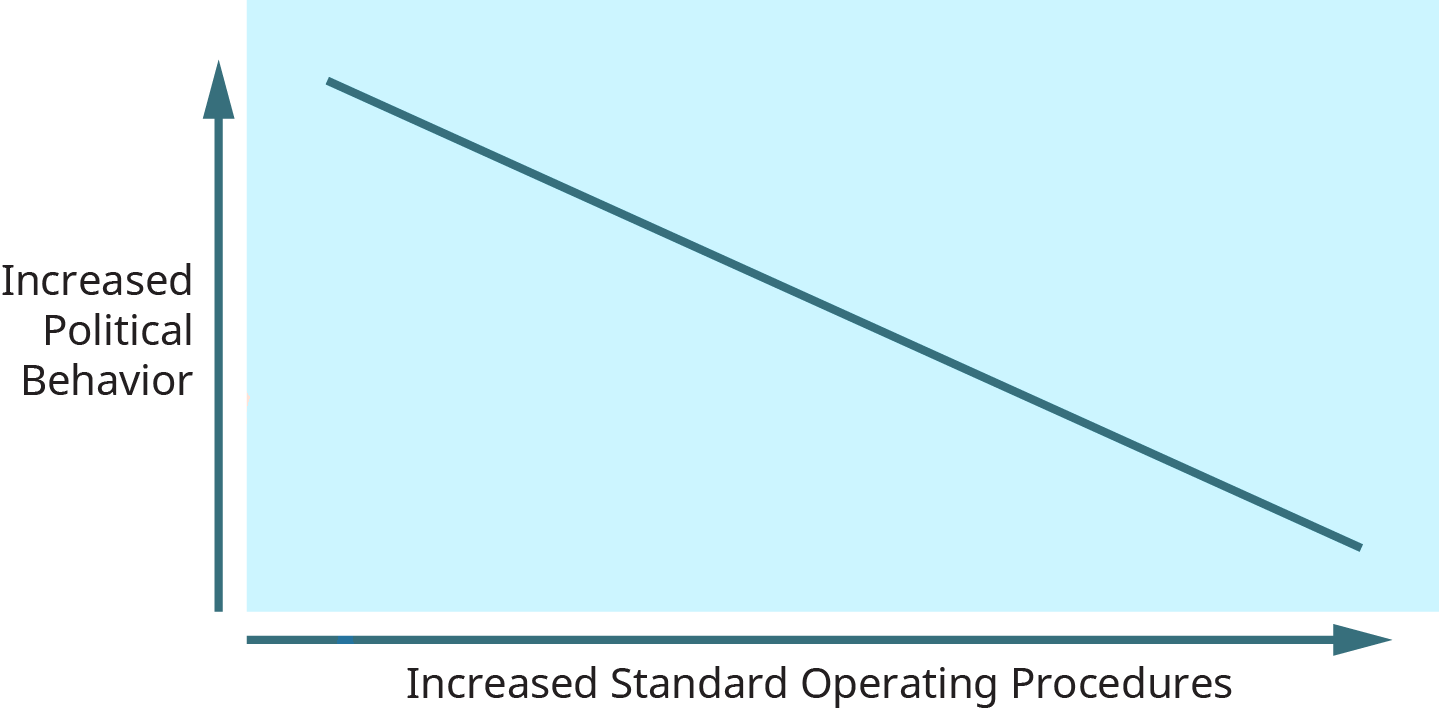

Because most organizations today have scarce resources, ambiguous goals, complex technologies, and sophisticated and unstable external environments, organizations often have policies and standard operating procedures (SOPs) in organizations. These policies are frequently aimed at reducing the extent to which politics influence a particular decision. This effort to encourage more “rational” decisions in organizations was a primary reason behind Max Weber’s development of the bureaucratic model. That is, increases in the specification of policy statements often are inversely related to political efforts, as shown in the table below. This is true primarily because such actions reduce the uncertainties surrounding a decision and hence the opportunity for political efforts.

Table 4.1 Examples of Conditions Conducive to Political Behavior

| Prevailing Conditions | Resulting Political Behaviors |

|---|---|

| Ambiguous goals | Attempts to define goals to ones advantage |

| Scarcity of resources | Fight to maximize ones share of resources |

| Ambiguity | Attempts to exploit uncertainty for personal gain |

| Democratic and non-programmed decisions | Attempts to make suboptimal decisions that favour personal ends |

| Performance evaluations and promotions | Attempts to use impression management to be viewed favourably |

| Source: Rice University, Organizational Behavior, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 | |

Influence

Starting at infancy, we all try to get others to do what we want. We learn early what works in getting us to our goals. Instead of crying and throwing a tantrum, we may figure out that smiling and using language causes everyone less stress and brings us the rewards we seek.

By the time you hit the workplace, you have had vast experience with influence techniques. You have probably picked out a few that you use most often. To be effective in a wide number of situations, however, it’s best to expand your repertoire of skills and become competent in several techniques, knowing how and when to use them as well as understanding when they are being used on you. If you watch someone who is good at influencing others, you will most probably observe that person switching tactics depending on the context. The more tactics you have at your disposal, the more likely it is that you will achieve your influence goals.

Self-Assessments

Commonly Used Influence Tactics

Researchers have identified distinct influence tactics and discovered that there are few differences between the way managers, subordinates, and peers use them, which we will discuss at greater depth later on in this chapter. We will focus on nine influence tactics. Recall our previous discussion of power and responses. Influence tactics can also produce responses of resistance, compliance, or commitment. Resistance occurs when the influence target does not wish to comply with the request and either passively or actively repels the influence attempt. Compliance occurs when the target does not necessarily want to obey, but they do. Commitment occurs when the target not only agrees to the request but also actively supports it as well. Within organizations, commitment helps to get things done, because others can help to keep initiatives alive long after compliant changes have been made or resistance has been overcome. Let’s talk about these influence tactics.

Rational Persuasion

Rational persuasion includes using facts, data, and logical arguments to try to convince others that your point of view is the best alternative. This is the most commonly applied influence tactic. One experiment illustrates the power of reason. People were lined up at a copy machine and another person, after joining the line asked, “May I go to the head of the line?” Amazingly, 63% of the people in the line agreed to let the requester jump ahead. When the line jumper makes a slight change in the request by asking, “May I go to the head of the line because I have copies to make?” the number of people who agreed jumped to over 90%. The word because was the only difference. Effective rational persuasion includes the presentation of information that is clear and specific, relevant, and timely. Across studies summarized in a meta-analysis, rationality was related to positive work outcomes (Higgens et al., 2003).

Inspirational Appeals

Inspirational appealsseek to tap into our values, emotions, and beliefs to gain support for a request or course of action. Effective inspirational appeals are authentic, personal, big-thinking, and enthusiastic.

Consultation

Consultation refers to the influence agent’s asking others for help in directly influencing or planning to influence another person or group. Consultation is most effective in organizations and cultures that value democratic decision making.

Ingratiation

Ingratiation refers to different forms of making others feel good about themselves. Ingratiation includes any form of flattery done either before or during the influence attempt. Research shows that ingratiation can affect individuals. For example, in a study of résumés, those résumés that were accompanied with a cover letter containing ingratiating information were rated higher than résumés without this information. Other than the cover letter accompanying them, the résumés were identical (Varma et al., 2006). Effective ingratiation is honest, infrequent, and well intended.

Personal Appeals

Personal appeals refers to helping another person because you like them and they asked for your help. We enjoy saying yes to people we know and like. A famous psychological experiment showed that in dorms, the most well-liked people were those who lived by the stairwell—they were the most often seen by others who entered and left the hallway. The repeated contact brought a level of familiarity and comfort. Therefore, personal appeals are most effective with people who know and like you.

Exchange

Exchange refers to give-and-take in which someone does something for you, and you do something for them in return. The rule of reciprocation says that “we should try to repay, in kind, what another person has provided us”(Cialdini, 2000, p. 20). The application of the rule obliges us and makes us indebted to the giver. One experiment illustrates how a small initial gift can open people to a substantially larger request at a later time. One group of subjects was given a bottle of Coke. Later, all subjects were asked to buy raffle tickets. On the average, people who had been given the drink bought twice as many raffle tickets as those who had not been given the unsolicited drinks.

Coalition Tactics

Coalition tacticsrefer to a group of individuals working together toward a common goal to influence others. Common examples of coalitions within organizations are unions that may threaten to strike if their demands are not met. Coalitions also take advantage of peer pressure. The influencer tries to build a case by bringing in the unseen as allies to convince someone to think, feel, or do something. A well-known psychology experiment draws upon this tactic. The experimenters stare at the top of a building in the middle of a busy street. Within moments, people who were walking by in a hurry stop and also look at the top of the building, trying to figure out what the others are looking at. When the experimenters leave, the pattern continues, often for hours. This tactic is also extremely popular among advertisers and businesses that use client lists to promote their goods and services. The fact that a client bought from the company is a silent testimonial.

Pressure

Pressure refers to exerting undue influence on someone to do what you want or else something undesirable will occur. This often includes threats and frequent interactions until the target agrees. Research shows that managers with low referent power tend to use pressure tactics more frequently than those with higher referent power (Yukl et al., 1996). Pressure tactics are most effective when used in a crisis situation and when they come from someone who has the other’s best interests in mind, such as getting an employee to an employee assistance program to deal with a substance abuse problem.

Legitimating

Legitimating tactics occur when the appeal is based on legitimate or position power. This tactic relies upon compliance with rules, laws, and regulations. It is not intended to motivate people but to align them behind a direction. Obedience to authority is filled with both positive and negative images. Position, title, knowledge, experience, and demeanor grant authority, and it is easy to see how it can be abused. If someone hides behind people’s rightful authority to assert themselves, it can seem heavy-handed and without choice. You must come across as an authority figure by the way you act, speak, and look. Think about the number of commercials with doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who look and sound the part, even if they are actors. People want to be convinced that the person is an authority worth heeding. Authority is often used as a last resort. If it does not work, you will not have much else to draw from in your goal to persuade someone.

Each of these influence tactics vary with the degree to which they are used and the outcomes that they provide. View Table 4.2 below To learn more.

Table 4.2 Influence Tactics Use and Outcomes

Original Data Source: Kipnis, D., Schmidt, S. M., & Wilkinson, J. (1980). Interorganizational influence tactics: Explorations in getting one’s way. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 440–452; Schriescheim, C. A., & Hinkin, T. R. (1990). Influence tactics used by subordinates: A theoretical and empirical analysis and refinement of Kipnis, Schmidt, and Wilkinson subscales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 132–140; Yukl, G., & Falbe, C. M. (1991). The Importance of different power sources in downward and lateral relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 416–423.

| Frequency of Use | Resistance | Compliance | Commitment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rational Persuasion | 54% | 47% | 30% | 23% |

| Legitimating | 13% | 44% | 56% | 0% |

| Personal Appeals | 7% | 25% | 33% | 42% |

| Exchange | 7% | 24% | 41% | 35% |

| Ingratiation | 6% | 41% | 28% | 31% |

| Pressure | 6% | 56% | 41% | 3% |

| Coalitions | 3% | 53% | 44% | 3% |

| Inspirational Appeals | 2% | 0% | 10% | 90% |

| Consultation | 2% | 18% | 27% | 55% |

| Source: Adapted from information in Falbe, C. M., & Yukl, G. (1992). Consequences for managers of using single influence tactics and combinations of tactics. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 638652.: Reproduced from Saylor Academy, Organizational Behavior, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. Converted to a table from an image. | ||||

Consider This: Making OB Connections

“You can make more friends in two months by becoming interested in other people than you can in two years by trying to get other people interested in you. “- Dale Carnegie

How to Win Friends and Influence People was written by Dale Carnegie in 1936 and has sold millions of copies worldwide. While this book first appeared over 70 years ago, the recommendations still make a great deal of sense regarding power and influence in modern-day organizations. For example, he recommends that in order to get others to like you, you should remember six things:

- Become genuinely interested in other people.

- Smile.

- Remember that a person’s name is to that person the sweetest and most important sound in any language.

- Be a good listener. Encourage others to talk about themselves.

- Talk in terms of the other person’s interests.

- Make the other person feel important—and do it sincerely.

This book relates to power and politics in a number of important ways. Carnegie specifically deals with enhancing referent power. Referent power grows if others like, respect, and admire you. Referent power is more effective than formal power bases and is positively related to employees’ satisfaction with supervision, organizational commitment, and performance. One of the keys to these recommendations is to engage in them in a genuine manner. This can be the difference between being seen as political versus understanding politics.

Direction of Influence

The type of influence tactic used tends to vary based on the target. For example, you would probably use different influence tactics with your boss, with employees working under you, or with a peer.

Upward Influence

Upward influence, as its name implies, is the ability to influence your manager and others in positions higher than yours. Upward influence may include appealing to a higher authority or citing the firm’s goals as an overarching reason for others to follow your cause. Upward influence can also take the form of an alliance with a higher status person (or with the perception that there is such an alliance) (Farmer & Maslyn, 1999; Farmer et al., 1997). As complexity grows, the need for this upward influence grows as well—the ability of one person at the top to know enough to make all the decisions becomes less likely. Moreover, even if someone did know enough, the sheer ability to make all the needed decisions fast enough is no longer possible. This limitation means that individuals at all levels of the organization need to be able to make and influence decisions. By helping higher-ups be more effective, employees can gain more power for themselves and their unit as well. On the flip side, allowing yourself to be influenced by those reporting to you may build your credibility and power as a leader who listens. Then, during a time when you do need to take unilateral, decisive action, others will be more likely to give you the benefit of the doubt and follow. Research establishes that subordinates’ use of rationality, assertiveness, and reciprocal exchange was related to more favorable outcomes such as promotions and raises, while self-promotion led to more negative outcomes (Orpen, 1996; Wayne et al., 1997).

Downward Influence

Downward influence is the ability to influence employees lower than you in the institutional hierarchy. This is best achieved through an inspiring vision. By articulating a clear vision, you help people see the end goal and move toward it. You often don’t need to specify exactly what needs to be done to get there—people will be able to figure it out on their own. An inspiring vision builds buy-in and gets people moving in the same direction. Research conducted within large savings banks shows that managers can learn to be more effective at influence attempts. The experimental group of managers received a feedback report and went through a workshop to help them become more effective in their influence attempts. The control group of managers received no feedback on their prior influence attempts. When subordinates were asked 3 months later to evaluate potential changes in their managers’ behavior, the experimental group had much higher ratings of the appropriate use of influence (Seifer et al., 2003). Research also shows that the better the quality of the relationship between the subordinate and their supervisor, the more positively resistance to influence attempts are seen (Tepper et al., 2006). In other words, managers who like their employees are less likely to interpret resistance as a problem.

Peer Influence

Peer influence occurs all the time. But, to be effective within organizations, peers need to be willing to influence each other without being destructively competitive (Cohen & Bradford, 2002). Research shows that across all functional groups of executives, finance or human resources as an example, rational persuasion is the most frequently used influence tactic (Enns et al., 2003). There are times to support each other and times to challenge—the end goal is to create better decisions and results for the organization and to hold each other accountable.

Adapted Works

“Organizational Power and Politics” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

“Power and Politics” in Organizational Behaviour by Saylor Academy and is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

References

Anderson, T. P. (1994). Creating measures of dysfunctional office and organizational politics: The DOOP and short-form DOOP scales psychology. Journal of Human Behavior, 31, 24–34.

Bandura, A. (1996). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Worth Publishers.

Brandon, R., & Seldman, M. (2004). Survival of the savvy: High-integrity political tactics for career and company success. Free Press.

Byrne, Z. S., Kacmar, C., Stoner, J., & Hochwarter, W. A. (2005). The relationship between perceptions of politics and depressed mood at work: Unique moderators across three levels. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(4), 330–343.

Cialdini, R. (2000). Influence: Science and practice. Allyn & Bacon.

Cohen, A., & Bradford, D. (2002). Power and influence in the 21st century. In S. Chowdhurt (Ed.), Organizations of the 21st century. Financial Times-Prentice Hall.

Enns, H. G., & McFarlin, D. B. (2003). When executives influence peers: Does function matter? Human Resource Management, 42, 125–142.

Farmer, S. M., & Maslyn, J. M. (1999). Why are styles of upward influence neglected? Making the case for a configurational approach to influences. Journal of Management, 25, 653–682.

Farmer, S. M., Maslyn, J. M., Fedor, D. B., & Goodman, J. S. (1997). Putting upward influence strategies in context. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 17–42.

Ferris, G. R., Fedor, D. B., & King, T. R. (1994). A political conceptualization of managerial behavior. Human Resource Management Review, 4, 1–34.

Ferris, G. R., Frink, D. D., Bhawuk, D. P., Zhou, J., & Gilmore, D. C. (1996). Reactions of diverse groups to politics in the workplace. Journal of Management, 22, 23–44.

Ferris, G. R., Frink, D. D., Galang, M. C., Zhou, J., Kacmar, K. M., & Howard, J. L. (1996). Perceptions of organizational politics: Prediction, stress-related implications, and outcomes, Human Relations, 49, 233–266.

Ferris, G. R., Perrewé, P. L., Anthony, W. P., & Gilmore, D. C. (2000). Political skill at work. Organizational Dynamics, 28, 25–37.

Harris, K. J., James, M., & Boonthanom, R. (2005). Perceptions of organizational politics and cooperation as moderators of the relationship between job strains and intent to turnover. Journal of Managerial Issues, 17, 26–42.

Hochwarter, W. A., Ferris, G. R., Laird, M. D., Treadway, D. C., & Gallagher, V. C. (2010). Nonlinear politics perceptions-work outcomes relationships: A three-study, five-sample investigation. Journal of Management, 36(3), 740–763. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308324065

Hochwarter, W. A., Witt, L. A., & Kacmar, K. M. (2000). Perceptions of organizational politics as a moderator of the relationship between conscientiousness and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 472–478.

Kacmar, K. L., Bozeman, D. P., Carlson, D. S., & Anthony, W. P. (1999). An examination of the perceptions of organizational politics model: Replication and extension. Human Relations, 52, 383–416.

Kacmar, K. M., & Ferris, G. R. (1989). Theoretical and methodological considerations in the age-job satisfaction relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 201–207.

Kilduff, M., & Day, D. (1994). Do chameleons get ahead? The effects of self-monitoring on managerial careers. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1047–1060.

Kotter, J. (1985). Power and influence. Free Press.

Lasswell, H. D. (1936). Politics: Who gets what, when, how. McGraw-Hill.

Maslyn, J. M., & Fedor, D. B. (1998). Perceptions of politics: Does measuring different loci matter? Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 645–653.

Muhammad, A. H. (2007, Fall). Antecedents of organizational politic perceptions in Kuwait business organizations. Competitiveness Review, 17(14), 234.

Nye, L. G., & Wit, L. A. (1993). Dimensionality and construct validity of the perceptions of politics scale (POPS). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53, 821–829.

Orpen, C. (1996). The effects of ingratiation and self promotion tactics on employee career success. Social Behavior and Personality, 24, 213–214.

Parker, C. P., Dipboye, R. L., & Jackson, S. L. (1995). Perceptions of organizational politics: An investigation of antecedents and consequences. Journal of Management, 21, 891–912.

Pfeffer, J. (2011). Power: Why some people have it and others don’t. Harper Business.

Randall, M. L., Cropanzano, R., Bormann, C. A., & Birjulin, A. (1999). Organizational politics and organizational support as predictors of work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 159–174.

Rosen, C., Levy, P., & Hall, R. (2006, January). Placing perceptions of politics in the context of the feedback environment, employee attitudes, and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(10), 21.

Seifer, C. F., Yukl, G., & McDonald, R. A. (2003). Effects of multisource feedback and a feedback facilitator on the influence behavior of managers toward subordinates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 561–569.

Tepper, B. J., Uhl-Bien, M., Kohut, G. F., Rogelberg, S. G., Lockhart, D. E., & Ensley, M. D. (2006). Subordinates’ resistance and managers’ evaluations of subordinates’ performance. Journal of Management, 32, 185–208.

Valle, M., & Perrewe, P. L. (2000). Do politics perceptions relate to political behaviors? Tests of an implicit assumption and expanded model. Human Relations, 53, 359–386.

Varma, A., Toh, S. M., & Pichler, S. (2006). Ingratiation in job applications: Impact on selection decisions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 200–210.

Wayne, S. J., Liden, R. C., Graf, I. K., & Ferris, G. R. (1997). The role of upward influence tactics in human resource decisions. Personnel Psychology, 50, 979–1006.

Yukl, G., Kim, H., & Falbe, C. M. (1996). Antecedents of influence outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 309–317.