3.3 Frameworks for Assessing Organizational Culture

Which values characterize an organization’s culture? Even though culture may not be immediately observable, identifying a set of values that might be used to describe an organization’s culture helps us identify, measure, and manage culture more effectively. For this purpose, several researchers have proposed various culture typologies. We will discuss four of these frameworks in this section.

In this section:

Organizational Culture Profile (OCP)

One typology that has received a lot of research attention is the Organizational Culture Profile (OCP), in which culture is represented by seven distinct values (Chatman & Jehn, 1991; O’Reilly, Chatman, & Caldwell, 1991).

Dimensions of Organizational Culture Profile: Detail-oriented, innovative, aggressive, outcome-oriented, stable, people-oriented, and team-oriented

Innovative Cultures

According to the OCP framework, companies that have innovative cultures are flexible and adaptable, and experiment with new ideas. These companies are characterized by a flat hierarchy in which titles and other status distinctions tend to be downplayed. In this company culture, employees do not have bosses in the traditional sense, and risk taking is encouraged by celebrating failures as well as successes (Deutschman, 2004). Companies such as W. L. Gore, Genentech Inc., and Google encourage their employees to take risks by allowing engineers to devote 20% of their time to projects of their own choosing (Deutschman, 2004; Morris et al., 2006).

Aggressive Cultures

Companies with aggressive cultures value competitiveness and outperforming competitors: By emphasizing this, they may fall short in the area of corporate social responsibility. For example, Microsoft Corporation is often identified as a company with an aggressive culture. The company has faced a number of antitrust lawsuits and disputes with competitors over the years. In aggressive companies, people may use language such as “We will kill our competition.” In the past, Microsoft executives often made statements such as “We are going to cut off Netscape’s air supply.…Everything they are selling, we are going to give away.” Its aggressive culture is cited as a reason for getting into new legal troubles before old ones are resolved (Green et al., 2004; Schlender, 1998). While Microsoft founder, Bill Gates, is no longer taking an active part in leadership in the company and efforts have been made to reduce the aggressive nature of the culture, claims of bullying and harassing behaviour are still making national headlines in the past few years.

Outcome-Oriented Cultures

The OCP framework describes outcome-oriented cultures as those that emphasize achievement, results, and action as important values. Outcome-oriented cultures hold employees as well as managers accountable for success and utilize systems that reward employee and group output. In these companies, it is more common to see rewards tied to performance indicators as opposed to seniority or loyalty. Research indicates that organizations that have a performance-oriented culture tend to outperform companies that are lacking such a culture (Nohria et al., 2003). At the same time, some outcome-oriented companies may have such a high drive for outcomes and measurable performance objectives that they may suffer negative consequences. Companies over-rewarding employee performance such as Enron Corporation and WorldCom experienced well-publicized business and ethical failures. When performance pressures lead to a culture where unethical behaviors become the norm, individuals see their peers as rivals and short-term results are rewarded; the resulting unhealthy work environment serves as a liability (Probst & Raisch, 2005).

Stable Cultures

Stable cultures are predictable, rule-oriented, and bureaucratic. These organizations aim to coordinate and align individual effort for greatest levels of efficiency. When the environment is stable and certain, these cultures may help the organization be effective by providing stable and constant levels of output (Westrum, 2004). These cultures prevent quick action, and as a result may be a misfit to a changing and dynamic environment. Public sector institutions may be viewed as stable cultures.

People-Oriented Cultures

People-oriented cultures value fairness, supportiveness, and respect for individual rights. These organizations truly live the mantra that “people are their greatest asset.” In addition to having fair procedures and management styles, these companies create an atmosphere where work is fun and employees do not feel required to choose between work and other aspects of their lives. In these organizations, there is a greater emphasis on and expectation of treating people with respect and dignity (Erdogan et al., 2006). One study of new employees in accounting companies found that employees, on average, stayed 14 months longer in companies with people-oriented cultures (Sheridan, 1992). Starbucks Corporation is an example of a people-oriented culture. The company pays employees above minimum wage, offers health care and tuition reimbursement benefits to its part-time as well as full-time employees, and has creative perks such as weekly free coffee for all associates. As a result of these policies, the company benefits from a turnover rate lower than the industry average (Weber, 2005; Motivation secrets, 2003). The company is routinely ranked as one of the best places to work.

Team-Oriented Cultures

Companies with team-oriented cultures are collaborative and emphasize cooperation among employees. For example, Southwest Airlines Company facilitates a team-oriented culture by cross-training its employees so that they are capable of helping each other when needed. The company also places emphasis on training intact work teams (Bolino & Turnley, 2003). In team-oriented organizations, members tend to have more positive relationships with their coworkers and particularly with their managers (Erdogan et al., 2006).

Detail-Oriented Cultures

Organizations with detail-oriented cultures are characterized in the OCP framework as emphasizing precision and paying attention to details. Such a culture gives a competitive advantage to companies in the hospitality industry by helping them differentiate themselves from others. McDonald’s Corporation specifies in detail how employees should perform their jobs by including photos of exactly how French fries and hamburgers should look when prepared properly (Fitch, 2004; Ford & Heaton, 2001; Kolesnikov-Jessop, 2005; Markels, 2007).

Service Culture

Service culture is not one of the dimensions of the CVF or the OCP, but given the importance of the retail industry in the overall economy, having a service culture can make or break an organization. Some of the organizations we have illustrated in this section, such as Nordstrom, Southwest Airlines, Ritz-Carlton, and Four Seasons are also famous for their service culture. In these organizations, employees are trained to serve the customer well, and cross-training is the norm. Employees are empowered to resolve customer problems in ways they see fit. Because employees with direct customer contact are in the best position to resolve any issues, employee empowerment is truly valued in these companies.

What differentiates companies with service culture from those without such a culture may be the desire to solve customer-related problems proactively. In other words, in these cultures employees are engaged in their jobs and personally invested in improving customer experience such that they identify issues and come up with solutions without necessarily being told what to do. For example, a British Airways baggage handler noticed that first-class passengers were waiting a long time for their baggage, whereas stand-by passengers often received their luggage first. Noticing this tendency, a baggage handler notified his superiors about this problem, along with the suggestion to load first-class passenger luggage last (Ford & Heaton, 2001). This solution was successful in cutting down the wait time by half. Such proactive behavior on the part of employees who share company values is likely to emerge frequently in companies with a service culture.

Safety Culture

Some jobs are safety sensitive. For example, logger, aircraft pilot, fishing worker, steel worker, and roofer are among the top 10 most dangerous jobs in the United States (Christie, 2005). In organizations where safety-sensitive jobs are performed, creating and maintaining a safety culture provides a competitive advantage, because the organization can reduce accidents, maintain high levels of morale and employee retention, and increase profitability by cutting workers’ compensation insurance costs. Some companies suffer severe consequences when they are unable to develop such a culture. For example, British Petroleum experienced an explosion in their Texas City, Texas, refinery in 2005, which led to the death of 15 workers while injuring 170. In December 2007, the company announced that it had already depleted the $1.6-billion fund to be used in claims for this explosion (Tennissen, 2007). A safety review panel concluded that the development of a safety culture was essential to avoid such occurrences in the future (Hofmann, 2007). In companies that have a safety culture, there is a strong commitment to safety starting at management level and trickling down to lower levels. Managers play a key role in increasing the level of safe behaviors in the workplace, because they can motivate employees day-to-day to demonstrate safe behaviors and act as safety role models. A recent study has shown that in organizations with a safety culture, leaders encourage employees to demonstrate behaviors such as volunteering for safety committees, making recommendations to increase safety, protecting coworkers from hazards, whistleblowing, and in general trying to make their jobs safer (Hofman et al., 2003; Smith, 2007).

The Competing Values Framework

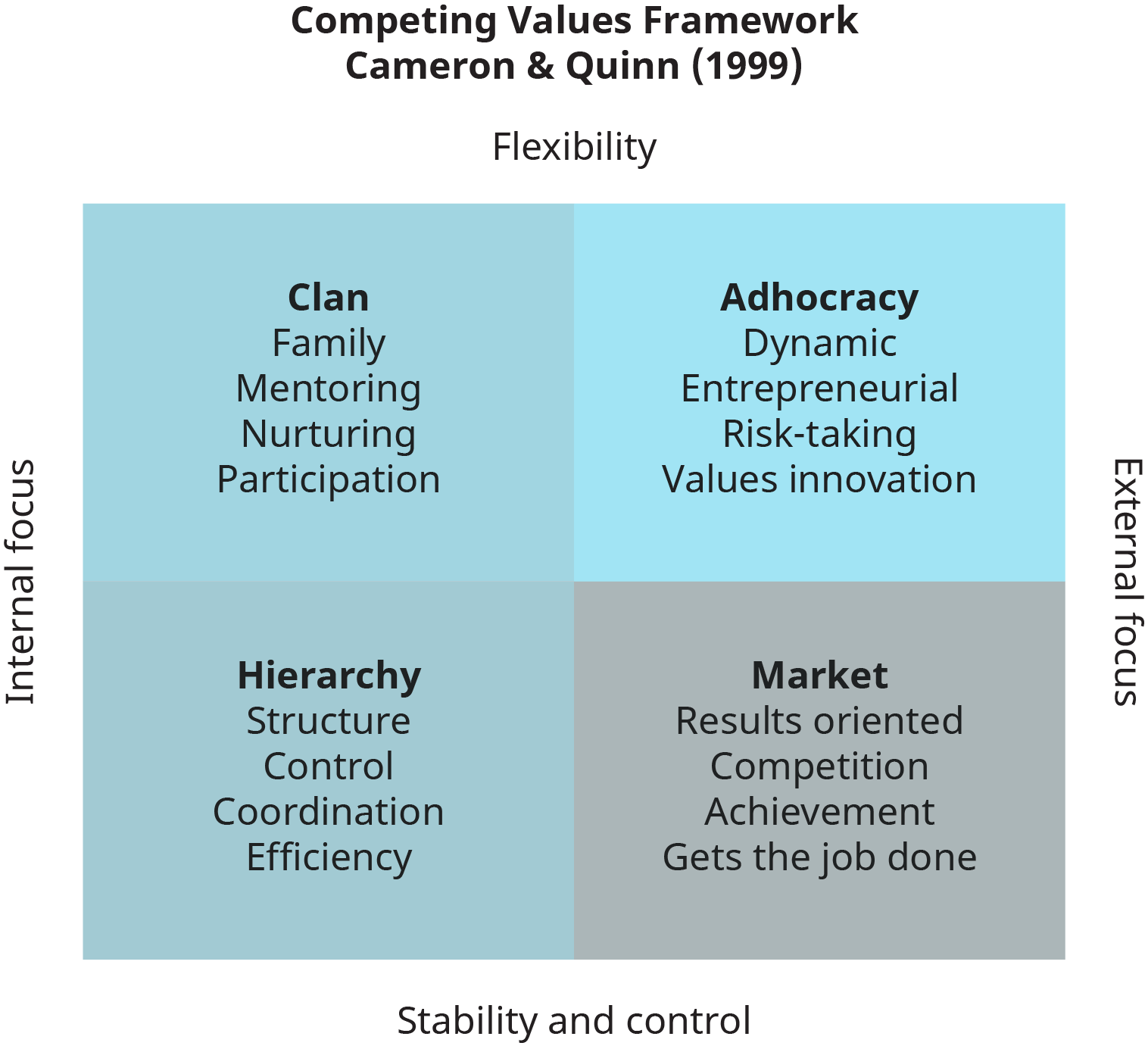

The Competing Values Framework (CVF) is one of the most cited and tested models for diagnosing an organization’s cultural effectiveness and examining its fit with its environment. The CVF, shown in Figure 3.7 has been tested for over 30 years; the effectiveness criteria offered in the framework were discovered to have made a difference in identifying organizational cultures that fit with particular characteristics of external environments (Cameron et al., 2014; Cameron & Quinn, 2006).

The two axes in the framework, external focus versus internal focus, indicate whether or not the organization’s culture is externally or internally oriented. The other two axes, flexibility versus stability and control, determine whether a culture functions better in a stable, controlled environment or a flexible, fast-paced environment. Combining the axes offers four cultural types: (1) the dynamic, entrepreneurial Adhocracy Culture—an external focus with a flexibility orientation; (2) the people-oriented, friendly Clan Culture—an internal focus with a flexibility orientation; (3) the process-oriented, structured Hierarchy Culture—an internal focus with a stability/control orientation; and (4) the results-oriented, competitive Market Culture—an external focus with a stability/control orientation.

The Adhocracy Culture

The adhocracy culture profile of an organization emphasizes creating, innovating, visioning the future, managing change, risk-taking, rule-breaking, experimentation, entrepreneurship, and uncertainty. This profile culture is often found in such fast-paced industries as filming, consulting, space flight, and software development. Facebook and Google’s cultures also match these characteristics (Yu & Wu, 2009). It should be noted, however, that larger organizations may have different cultures for different groupings of professionals, even though the larger culture is still dominant. For example, a different subculture may evolve for hourly workers as compared to PhD research scientists in an organization.

The Clan Culture

The Clan Culture type focuses on relationships, team building, commitment, empowering human development, engagement, mentoring, and coaching. Organizations that focus on human development, human resources, team building, and mentoring would fit this profile. This type of culture fits Tom’s of Maine, which has strived to form respectful relationships with employees, customers, suppliers, and the physical environment.

The Hierarchy Culture

The Hierarchy Culture emphasizes efficiency, process and cost control, organizational improvement, technical expertise, precision, problem solving, elimination of errors, logical, cautious and conservative, management and operational analysis, and careful decision-making. This profile would suit a company that is bureaucratic and structured, such government agencies.

The Market Culture

The Market Culture focuses on delivering value, competing, delivering shareholder value, goal achievement, driving and delivering results, speedy decisions, hard driving through barriers, directive, commanding, and getting things done. This profile suits a marketing-and-sales-oriented company that works on planning and forecasting but also getting products and services to market and sold. Oracle under the dominating, hard-charging executive chairman Larry Ellison characterized this cultural fit.

Adapted Works

“Characteristics of Organizational Culture” in Organizational Behavior by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Corporate Cultures” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2003). Going the extra mile: Cultivating and managing employee citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Executive, 17, 60–71.

Cameron, K., & Quinn, R. (2006). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework. Jossey-Bass.

Cameron, K., Quinn, R., Degraff, J., & Thakor, A. (2014). Competing values leadership (2nd ed.). New Horizons in Management.

Christie, L. (2005). America’s most dangerous jobs. Survey: Loggers and fisherman still take the most risk; roofers record sharp increase in fatalities. CNN/Money. http://money.cnn.com/2005/08/26/pf/jobs_jeopardy/

Deutschman, A. (2004, December). The fabric of creativity. Fast Company, 89, 54–62.

Erdogan, B., Liden, R. C., & Kraimer, M. L. (2006). Justice and leader-member exchange: The moderating role of organizational culture. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 395–406.

Fitch, S. (2004, May 10). Soft pillows and sharp elbows. Forbes, 173, 66–78.

Ford, R. C., & Heaton, C. P. (2001). Lessons from hospitality that can serve anyone. Organizational Dynamics, 30, 30–47.

Hofmann, M. A. (2007, January 22). BP slammed for poor leadership on safety. Business Insurance, 41, 3–26.

Kolesnikov-Jessop, S. (2005, November). Four Seasons Singapore: Tops in Asia. Institutional Investor, 39, 103–104.

Markels, A. (2007, April 23). Dishing it out in style. U.S. News & World Report, 142, 52–55.

Morris, B., Burke, D., & Neering, P. (2006, January 23). The best place to work now. Fortune, 153, 78–86.

Motivation secrets of the 100 best employers. (2003, October). HR Focus, 80, 1–15.

Nohria, N., Joyce, W., & Roberson, B. (2003, July). What really works. Harvard Business Review, 81, 42–52.

Probst, G., & Raisch, S. (2005). Organizational crisis: The logic of failure. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 90–105.

Schlender, B. (1998, June 22). Gates’ crusade. Fortune, 137, 30–32.

Sheridan, J. (1992). Organizational culture and employee retention. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 1036–1056.

Smith, S. (2007, November). Safety is electric at M. B. Herzog. Occupational Hazards, 69, 42.

Tennissen, M. (2007, December 19). Second BP trial ends early with settlement. Southeast Texas Record.

Weber, G. (2005, February). Preserving the counter culture. Workforce Management, 84, 28–34.

Westrum, R. (2004, August). Increasing the number of guards at nuclear power plants. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 24, 959–961.

Yu, T, & Wu, N. (2009). A review of study on the Competing Values Framework. International Journal of Business Management, 4(7), 47–42.