2.3 Conflict Resolution Strategies

In this Section:

Common Strategies that Seldom Work

We have discovered that conflict is pervasive throughout organizations and that some conflict can be good for organizations. People often grow and learn from conflict, as long as the conflict is not dysfunctional. The challenge is to select a resolution strategy appropriate to the situation and individuals involved. A review of past management practice in this regard reveals that managers often make poor strategy choices. At leave five conflict resolution techniques commonly found in organizations prove to be ineffective fairly consistently (Miles, 1980). Let’s review these strategies and why they are ineffective.

Nonaction

Perhaps the most common managerial response when conflict emerges is nonaction—doing nothing and ignoring the problem. This aligns with the avoidance strategy in the Thomas-Kilmann model discussed in the previous section. It may be felt that if the problem is ignored, it will go away. Unfortunately, that is not often the case. In fact, ignoring the problem may serve only to increase the frustration and anger of the parties involved.

Administrative Orbiting

In some cases, managers will acknowledge that a problem exists but then take little serious action. Instead, they continually report that a problem is “under study” or that “more information is needed.” Telling a person who is experiencing a serious conflict that “these things take time” hardly relieves anyone’s anxiety or solves any problems. This ineffective strategy for resolving conflict is aptly named administrative orbiting.

Due Process Nonaction

A third ineffective approach to resolving conflict is to set up a recognized procedure for redressing grievances but at the same time to ensure that the procedure is long, complicated, costly, and perhaps even risky. The due process nonaction strategy is to wear down the dissatisfied employee while at the same time claiming that resolution procedures are open and available. This technique has been used repeatedly in conflicts involving race and sex discrimination. When we discuss conflict policies, one key consideration will be to have clear and timely deadlines for addressing conflicts.

Secrecy

Oftentimes, managers will attempt to reduce conflict through secrecy. Some feel that by taking secretive actions, controversial decisions can be carried out with a minimum of resistance. One argument for pay secrecy (keeping employee salaries secret) is that such a policy makes it more difficult for employees to feel inequitably treated. Essentially, this is a “what they don’t know won’t hurt them” strategy. A major problem of this approach is that it leads to distrust of management. When managerial credibility is needed for other issues, it may be found lacking.

Character Assassination

The final ineffective resolution technique to be discussed here is character assassination. The person with a conflict, perhaps a person claiming sex discrimination, is labeled a “troublemaker.” Attempts are made to discredit the person and distance them from the others in the group. The implicit strategy here is that if the person can be isolated and stigmatized, they will either be silenced by negative group pressures or they will leave the organization. In either case, the problem is “solved.”

Strategies for Preventing and Reducing Conflict

On the more positive side, there are many things managers can do to reduce or actually solve dysfunctional conflict when it occurs. These fall into two categories: actions directed at conflict prevention and actions directed at conflict reduction.

Strategies for Preventing Conflict

We shall start by examining conflict prevention techniques, because preventing conflict is often easier than reducing it once it begins. These include:

- Emphasizing organization-wide goals and effectiveness

Focusing on organization-wide goals and objectives should prevent goal conflict. If larger goals are emphasized, employees are more likely to see the big picture and work together to achieve corporate goals. - Providing stable, well-structured tasks.

When work activities are clearly defined, understood, and accepted by employees, conflict should be less likely to occur. Conflict is most likely to occur when task uncertainty is high; specifying or structuring jobs minimizes ambiguity. - Facilitating intergroup communication.

Misperception of the abilities, goals, and motivations of others often leads to conflict, so efforts to increase the dialogue among groups and to share information should help eliminate conflict. As groups come to know more about one another, suspicions often diminish, and greater intergroup teamwork becomes possible. - Avoiding win-lose situations

If win-lose situations are avoided, less potential for conflict exists. When resources are scarce, management can seek some form of resource sharing to achieve organizational effectiveness. Moreover, rewards can be given for contributions to overall corporate objectives; this will foster a climate in which groups seek solutions acceptable to all.

Strategies for Reducing Conflict

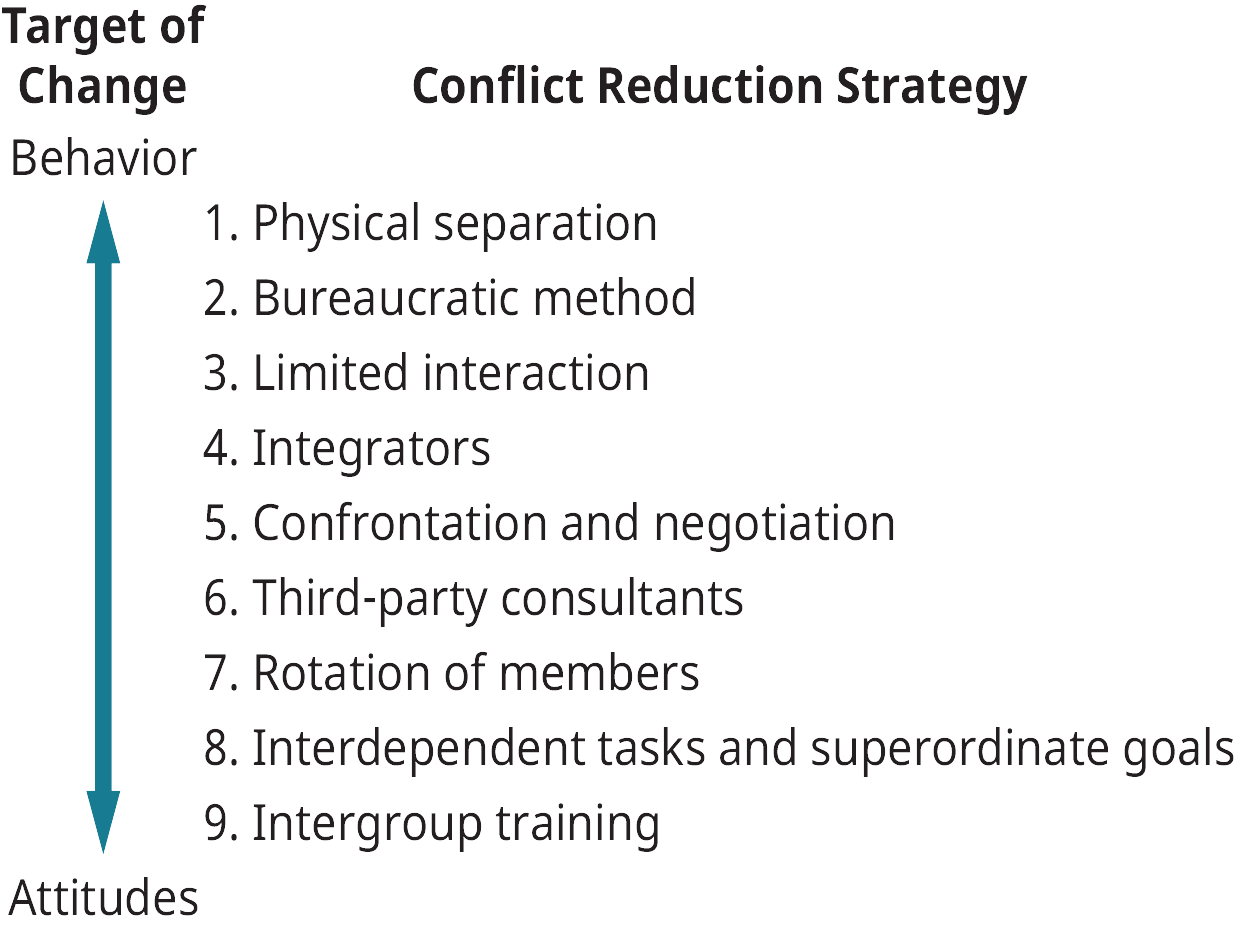

Where dysfunctional conflict already exists, something must be done, and managers may pursue one of at least two general approaches: they can try to change employee attitudes, or they can try to change employee behaviors. If they change behavior, open conflict is often reduced, but groups may still dislike one another; the conflict simply becomes less visible as the groups are separated from one another. Changing attitudes, on the other hand, often leads to fundamental changes in the ways that groups get along. However, it also takes considerably longer to accomplish than behavior change because it requires a fundamental change in social perceptions.

Nine conflict reduction strategies are shown in Figure 2.4. The techniques should be viewed as a continuum, ranging from strategies that focus on changing behaviors near the top of the scale to strategies that focus on changing attitudes near the bottom of the scale.

Let’s Focus: Reduction Strategies

Nine Conflict Reduction Strategies

- Physical separation: The quickest and easiest solution to conflict is physical separation. Separation is useful when conflicting groups are not working on a joint task or do not need a high degree of interaction. Though this approach does not encourage members to change their attitudes, it does provide time to seek a better accommodation.

- Use of rules and regulations: Conflict can also be reduced through the increasing specification of rules, regulations, and procedures. This approach, also known as the bureaucratic method, imposes solutions on groups from above. Again, however, basic attitudes are not modified.

- Limiting intergroup interaction: Another approach to reducing conflict is to limit intergroup interaction to issues involving common goals. Where groups agree on a goal, cooperation becomes easier.

- Use of integrators: Integrators are individuals who are assigned a boundary-spanning role between two groups or departments. To be trusted, integrators must be perceived by both groups as legitimate and knowledgeable. The integrator often takes the “shuttle diplomacy” approach, moving from one group to another, identifying areas of agreement, and attempting to find areas of future cooperation.

- Confrontation and negotiation: In this approach, competing parties are brought together face-to-face to discuss their basic areas of disagreement. The hope is that through open discussion and negotiation, means can be found to work out problems. Contract negotiations between union and management represent one such example. If a “win-win” solution can be identified through these negotiations, the chances of an acceptable resolution of the conflict increase. (More will be said about this in upcoming sections of this chapter.)

- Third-party consultation: In some cases, it is helpful to bring in outside consultants for third-party consultation who understand human behavior and can facilitate a resolution. A third-party consultant not only serves as a go-between but can speak more directly to the issues, because she is not a member of either group. We will talk more about third party consultants later in this chapter.

- Rotation of members: By rotating from one group to another, individuals come to understand the frames of reference, values, and attitudes of other members; communication is thus increased. When those rotated are accepted by the receiving groups, change in attitudes as well as behavior becomes possible. This is clearly a long-term technique, as it takes time to develop good interpersonal relations and understanding among group members.

- Identification of interdependent tasks and superordinate goals: A further strategy for management is to establish goals that require groups to work together to achieve overall success—for example, when company survival is threatened. The threat of a shutdown often causes long-standing opponents to come together to achieve the common objective of keeping the company going.

- Use of intergroup training: The final technique on the continuum is intergroup training. Outside training experts are retained on a long-term basis to help groups develop relatively permanent mechanisms for working together. Structured workshops and training programs can help forge more favorable intergroup attitudes and, as a result, more constructive intergroup behavior.

Works Adapted

“Conflict and Negotiations” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

Miles, R. (1980). Macro organizational behavior. Scott Foresman.