10.2 Self-Esteem, Communication and Relationship Dispositions

In this section:

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is an individual’s subjective evaluation of their abilities and limitations. You may be wondering the importance of self-esteem in interpersonal communication. Self-esteem and communication have a reciprocal relationship (as depicted in Figure 10.3). Our communication with others impacts our self-esteem, and our self-esteem impacts our communication with others. As such, our self-esteem and communication are constantly being transformed by each other.

Interpersonal communication and self-esteem cannot be separated. Now, our interpersonal communication is not the only factor that impacts self-esteem, but interpersonal interactions are one of the most important tools we have in developing our selves.

Self-Compassion

Some researchers have argued that self–esteem as the primary measure of someone’s psychological health may not be wise because it stems from comparisons with others and judgments. As such, Kristy Neff (2003) has argued for the use of the term self-compassion.

Self-Compassion stems out of the larger discussion of compassion. Compassion then is about the sympathetic consciousness for someone who is suffering or unfortunate. Self-compassion “involves being touched by and open to one’s own suffering, not avoiding or disconnecting from it, generating the desire to alleviate one’s suffering and to heal oneself with kindness. Self-compassion also involves offering nonjudgmental understanding to one’s pain, inadequacies and failures, so that one’s experience is seen as part of the larger human experience” (Neff, 2003, p. 86-87). Neff argues that self-compassion can be broken down into three distinct categories: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness (see Figure 10.4)

Self-Kindness

Humans have a really bad habit of beating ourselves up. As the saying goes, we are often our own worst enemies. Self-kindness is simply extending the same level of care and understanding to ourselves as we would to others. Instead of being harsh and judgmental, we are encouraging and supportive. Instead of being critical, we are empathic towards ourselves. Now, this doesn’t mean that we just ignore our faults and become narcissistic (excessive interest in oneself), but rather we realistically evaluate ourselves.

Common Humanity

The second factor of self-compassion is common humanity, or “seeing one’s experiences as part of the larger human experience rather than seeing them as separating and isolating” (Neff, 2003, p. 89). As Kristen Neff and Christopher Germer (2018) realize, we’re all flawed works in progress. No one is perfect. No one is ever going to be perfect. We all make mistakes (some big, some small). We’re also all going to experience pain and suffering in our lives. Being self-compassionate is approaching this pain and suffering and seeing it for what it is, a natural part of being human. “The pain I feel in difficult times is the same pain you feel in difficult times. The circumstances are different, the degree of pain is different, but the basic experience of human suffering is the same” (Neff & Germer, 2018, p. 11).

Mindfulness

The final factor of self-compassion is mindfulness. Although Neff (2003) defines mindfulness in the same terms we’ve been discussing in this text, she specifically addresses mindfulness as a factor of pain, so she defines mindfulness, with regards to self-compassion, as “holding one’s painful thoughts and feelings in balanced awareness rather than over-identifying with them” (p. 89). Essentially, Neff argues that mindfulness is an essential part of self-compassion, because we need to be able to recognize and acknowledge when we’re suffering so we can respond with compassion to ourselves.

Let’s Practice: Mindfulness Activity

One of the beautiful things about mindfulness is that it positively impacts someone’s self-esteem (Pepping et al., 2013). It’s possible that people who are higher in mindfulness report higher self-esteem because of the central tenant of non-judgment. People with lower self-esteems often report highly negative views of themselves and their past experiences in life. These negative judgments can start to wear someone down.

One of the beautiful things about mindfulness is that it positively impacts someone’s self-esteem (Pepping et al., 2013). It’s possible that people who are higher in mindfulness report higher self-esteem because of the central tenant of non-judgment. People with lower self-esteems often report highly negative views of themselves and their past experiences in life. These negative judgments can start to wear someone down.

Christopher Pepping, Analise O’Donovan, and Penelope J. Davis (2013) believe that mindfulness practice can help improve one’s self-esteem for four reasons:

- Labeling internal experiences with words, which might prevent people from getting consumed by self-critical thoughts and emotions;

- Bringing a non-judgmental attitude toward thoughts and emotions, which could help individuals have a neutral, accepting attitude toward the self;

- Sustaining attention on the present moment, which could help people avoid becoming caught up in self-critical thoughts that relate to events from the past or future;\

- Letting thoughts and emotions enter and leave awareness without reacting to them (Nauman, 2014).

For this exercise, think about a recent situation where you engaged in self-critical thoughts.

- What types of phrases ran through your head? Would you have said these to a friend? If not, why do you say them to yourself?

- What does the negative voice in your head sound like? Is this voice someone you want to listen to? Why?

- Did you try temporarily distracting yourself to see if the critical thoughts would go away (e.g., mindfulness meditation, coloring, exercise, etc.)? If yes, how did that help? If not, why?

- Did you examine the evidence? What proof did you have that the self-critical thought was true?

- Was this a case of a desire to improve yourself or a case of non-compassion towards yourself?

Sources: Nauman, E. (2014, March 10). Feeling self-critical? Try mindfulness. Greater Good Magazine. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/feeling_self_critical_try_mindfulness; Pepping, C. A., O’Donovan, A., & Davis, P. J. (2013). The positive effects of mindfulness on self-esteem. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(5), 376-386. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.807353

Communication Dispositions

In our chapter on personality, we examined cognitive and personal-social dispositions. In addition, there are several intrapersonal dispositions studied specifically by communication scholars. Communication dispositions are general patterns of communicative behavior. In this section, we will explore the nature of introversion/extraversion, approach and avoidance traits, argumentativeness /verbal aggressiveness, and lastly, sociocommunicative orientation (Daly, 2011).

Introversion/Extraversion

The concept of introversion/extraversion is one that has been widely studied by both psychologists and communication researchers. The idea is that people exist on a continuum that exists from highly extraverted (an individual’s likelihood to be talkative, dynamic, and outgoing) to highly introverted (an individual’s likelihood to be quiet, shy, and more reserved).There is a considerable amount of research that has found an individual’s tendency toward extraversion or introversion is biologically based (Beatty et al., 2001). As such, where you score on the Introversion Scale may largely be a factor of your genetic makeup and not something you can alter greatly. When it comes to interpersonal relationships, individuals who score highly on extraversion tended to be perceived by others as intelligent, friendly, and attractive. As such, extraverts tend to have more opportunities for interpersonal communication; it’s not surprising that they tend to have better communicative skills when compared to their more introverted counterparts.

Let’s Practice

Want to know how you score on the introversion/extroversion continuum Consider completing the Introversion Scale created by James C. McCroskey. It’s available on his website:

Want to know how you score on the introversion/extroversion continuum Consider completing the Introversion Scale created by James C. McCroskey. It’s available on his website:

Approach and Avoidance Traits

The second set of communication dispositions are categorized as approach and avoidance traits. According to Virginia Richmond, Jason Wrench, and James McCroskey (2018), approach and avoidance traits depict the tendency an individual has to either willingly approach or avoid situations where they will have to communicate with others. To help us understand the approach and avoidance traits, we’ll examine three specific traits commonly discussed by communication scholars: shyness, communication apprehension, and willingness to communicate.

Shyness

In a classic study conducted by Philip Zimbardo (1977), he asked two questions to over 5,000 participants: Do you presently consider yourself to be a shy person? If “No,” was there ever a period in your life during which you considered yourself to be a shy person? The results of these two questions were quite surprising. Over 40% said that they considered themselves to be currently shy. Over 80% said that they had been shy at one point in their lifetimes. Another, more revealing measure of shyness, was created by James C. McCroskey and Virginia Richmond (1982).

According to Arnold Buss (2009), shyness involves discomfort when an individual is interacting with another person(s) in a social situation. Buss further clarifies the concept by differentiating between anxious shyness and self-conscious shyness. Anxious shyness involves the fear associated with dealing with others face-to-face. Anxious shyness is initially caused by a combination of strangers, novel settings, novel social roles, fear of evaluation, or fear of self-presentation. However, long-term anxious shyness is generally caused by chronic fear, low sociability, low self-esteem, loneliness, and avoidance conditioning. Self-conscious shyness, on the other hand, involves feeling conspicuous or socially exposed when dealing with others face-to-face. Self-conscious shyness is generally initially caused by feelings of conspicuousness, breaches of one’s privacy, teasing/ridicule/bullying, overpraise, or one’s foolish actions. However, long-term self-conscious shyness can be a result of socialization, public self-consciousness, history of teasing/ridicule/bullying, low self-esteem, negative appearance, and poor social skills.

Whether one suffers from anxious or self-conscious shyness, the general outcome is a detriment to an individual’s interpersonal interactions with others. Generally speaking, shy individuals have few opportunities to engage in interpersonal interactions with others, so their communicative skills are not as developed as their less-shy counterparts. This lack of skill practice tends to place a shy individual in a never-ending spiral where they always feels just outside the crowd.

Let’s Practice

Learn about your own level of shyness by completing the Shyness Scale.

Learn about your own level of shyness by completing the Shyness Scale.

- It’s available at http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/measures/shyness.htm

Communication Apprehension

James C. McCroskey started examining the notion of anxiety in communicative situations during the late 1960s. Since that time, research on communication apprehension has been one of the most commonly studied variables in the field. McCroskey (1977) defined communication apprehension as the fear or anxiety “associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons” (p. 28). Although many different measures have been created over the years examining communication apprehension, the most prominent one has been James C. McCroskey’s (1982) Personal Report of Communication Apprehension-24 (PRCA-24).

The PRCA-24 evaluates four distinct types of communication apprehension (CA): interpersonal CA, group CA, meeting CA, and public CA. Interpersonal CA examines the extent to which individuals experience fear or anxiety when thinking about or actually interacting with another person (For more on the topic of CA as a general area of study, read Richmond, Wrench, and McCroskey’s (2018) book, Communication Apprehension, Avoidance, and Effectiveness). Interpersonal CA impacts people’s relationship development almost immediately. In one experimental study by Colby et al. (1993), researchers paired people and had them converse for 15 minutes. At the end of the 15-minute conversation, the researchers had both parties rate the other individual. The results indicated that high-CAs (highly communicative apprehensive people) were perceived as less attractive, less trustworthy, and less satisfied than low-CAs (people with low levels of communication apprehension). Generally speaking, high-CAs don’t tend to fare well in most of the research in interpersonal communication.

Let’s Practice

You can complete James C. McCroskey’s Personal Report of Communication Apprehension to learn about your own profile of communication apprehension.

You can complete James C. McCroskey’s Personal Report of Communication Apprehension to learn about your own profile of communication apprehension.

Willingness to Communicate

The final of our approach and avoidance traits is the willingness to communicate (WTC). James McCroskey and Virginia Richmond (1987)originally coined the WTC concept as an individual’s predisposition to initiate communication with others. Willingness to communicate examines an individual’s tendency to initiate communicative interactions with other people.

People who have high WTC levels are going to be more likely to initiate interpersonal interactions than those with low WTC levels. However, just because someone is not likely to initiate conversations doesn’t mean that he or she is unable to actively and successfully engage in interpersonal interactions. For this reason, we refer to WTC as an approach trait because it describes an individual’s likelihood of approaching interactions with other people. As noted by Richmond et al. (2013), “People with a high WTC attempt to communicate more often and work harder to make that communication effective than people with a low WTC, who make far fewer attempts and often aren’t as effective at communicating” (p. 18).

Let’s Practice

You can take the Willingness To Communicate (WTC) scale at James C. McCroskey’s website

You can take the Willingness To Communicate (WTC) scale at James C. McCroskey’s website

Argumentativeness and Verbal Aggressiveness

Starting in the mid-1980s, Dominic Infante and Charles Wigley (1986) defined verbal aggression as “the tendency to attack the self-concept of individuals instead of, or in addition to, their positions on topics of communication” (p. 61). Notice that this definition specifically is focused on the attacking of someone’s self-concept or an individual’s attitudes, opinions, and cognitions about one’s competence, character, strengths, and weaknesses. For example, if someone perceives themselves as a good worker, then a verbally aggressive attack would demean that person’s quality of work or their ability to do future quality work. In a study conducted by Terry Kinney (1994), he found that self-concept attacks happen on three basic fronts: group membership (e.g., “Your whole division is a bunch of idiots!”), personal failings (e.g., “No wonder you keep getting passed up for a promotion!”), and relational failings (e.g., “No wonder your spouse left you!”).

Now that we’ve discussed what verbal aggression is, we should delineate verbal aggression from another closely related term, argumentativeness. According to Dominic Infante and Andrew Rancer (1982), argumentativeness is a communication trait that “predisposes the individual in communication situations to advocate positions on controversial issues, and to attacking verbally the positions which other people take on these issues” (p. 72). You’ll notice that argumentativeness occurs when an individual attacks another’s positions on various issues; whereas, verbal aggression occurs when an individual attacks someone’s self-concept instead of attack another’s positions. Argumentativeness is seen as a constructive communication trait, while verbal aggression is a destructive communication trait.

Individuals who are highly verbally aggressive are not liked by those around them (Myers & Johnson, 2003). Researchers have seen this pattern of results across different relationship types. Highly verbally aggressive individuals tend to justify their verbal aggression in interpersonal relationships regardless of the relational stage (new vs. long-term relationship) (Martin et al., 1996). In an interesting study conducted by Beth Semic and Daniel Canary (1996), the two set out to watch interpersonal interactions and the types of arguments formed during those interactions based on individuals’ verbal aggressiveness and argumentativeness. The researchers had friendship-dyads come into the lab and were asked to talk about two different topics. The researchers found that highly argumentative individuals did not differ in the number of arguments they made when compared to their low argumentative counterparts. However, highly verbally aggressive individuals provided far fewer arguments when compared to their less verbally aggressive counterparts. Although this study did not find that highly argumentative people provided more (or better) arguments, highly verbally aggressive people provided fewer actual arguments when they disagreed with another person. Overall, verbal aggression and argumentativeness have been shown to impact several different interpersonal relationships.

Sociocommunicative Orientation

In the mid to late 1970s, Sandra Bem began examining psychological gender orientation. In her theorizing of psychological gender, Bem (1974) measured two constructs, masculinity and femininity, using a scale she created called the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI). Her measure was designed to evaluate an individual’s femininity or masculinity. Bem defined masculinity as individuals exhibiting perceptions and traits typically associated with males, and femininity as individuals exhibiting perceptions and traits usually associated with females. Individuals who adhered to both their biological sex and their corresponding psychological gender (masculine males, feminine females) were considered sex-typed. Individuals who differed between their biological sex and their corresponding psychological gender (feminine males, masculine females) were labeled cross-sex typed. Lastly, some individuals exhibited both feminine and masculine traits, and these individuals were called androgynous.

Virginia Richmond and James McCroskey (1985) opted to discard the biological sex-biased language of “masculine” and “feminine” for the more neutral language of “assertiveness” and “responsiveness.” The combination of assertiveness and responsiveness was called someone’s sociocommunicative orientation, which emphasizes that Bem’s notions of gender are truly representative of communicator traits and not one’s biological sex (Richmond & McCroskey, 1990).

Responsiveness

Responsiveness refers to an individual who “considers other’s feelings, listens to what others have to say, and recognizes the needs of others” (Richmond & McCroskey, 1990, p. 449-450). If you filled out the Sociocommunicative Orientation Scale, you would find that the words associated with responsiveness include the following: helpful, responsive to others, sympathetic, compassionate, sensitive to the needs of others, sincere, gentle, warm, tender, and friendly.

Assertiveness

Assertiveness refers to individuals who “can initiate, maintain, and terminate conversations, according to their interpersonal goals” (Richmond & Martin, 1998, p. 136). If you filled out the Sociocommunicative Orientation Scale, you would find that the words associated with assertiveness include the following: defends own beliefs, independent, forceful, has a strong personality, assertive, dominant, willing to take a stand, acts as a leader, aggressive, and competitive.

Versatility

Communication always exists within specific contexts, so picking a single best style to communicate in every context simply can’t be done because not all patterns of communication are appropriate or effective in all situations. As such, McCroskey and Richmond added a third dimension to the mix that they called versatility(McCroskey&Richmond,1996).In essence, individuals who are competent communicators know when it is both appropriate and effective to use both responsiveness and assertiveness. The notion of pairing the two terms against each other did not make sense to McCroskey and Richmond because both were so important. Other terms scholars have associated with versatility include “adaptability, flexibility, rhetorical sensitivity, and style flexing” (Richomond & Martin, 1998, p. 138). The opposite of versatility was also noted by McCroskey and Richmond, who saw such terms as dogmatic, rigid, uncompromising, and unyielding as demonstrating the lack of versatility.

Let’s Practice: Sociocommunicative Orientation and Interpersonal Communication

orientation has been examined in several studies that relate to interpersonal communication. In a study conducted by Brian Patterson and Shawn Beckett (1995), the researchers sought to see the importance of sociocommunicative orientation and how people repair relationships. Highly assertive individuals were found to take control of repair situations. Highly responsive individuals, on the other hand, tended to differ in their approaches to relational repair, depending on whether the target was perceived as assertive or responsive.

orientation has been examined in several studies that relate to interpersonal communication. In a study conducted by Brian Patterson and Shawn Beckett (1995), the researchers sought to see the importance of sociocommunicative orientation and how people repair relationships. Highly assertive individuals were found to take control of repair situations. Highly responsive individuals, on the other hand, tended to differ in their approaches to relational repair, depending on whether the target was perceived as assertive or responsive.

When a target was perceived as highly assertive, the responsive individual tended to let the assertive person take control of the relational repair process. When a target was perceived as highly responsive, the responsive individual was more likely to encourage the other person to self-disclose and took on the role of the listener.

As a whole, highly assertive individuals were more likely to stress the optimism of the relationship, while highly responsive individuals were more likely to take on the role of a listener during the relational repair.

- You can take the Bem Sex-Role Inventory at http://garote.bdmonkeys.net/bsri.htmland

- You can take the Sociocommunicative Orientation Scale at http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/measures/sco.htm

Relational Dispositions

The final three dimensions proposed by John Daly (2011) were relational dispositions. Relational dispositions are general patterns of mental processes that impact how people view and organize themselves in relationships. For our purposes, we’ll examine two unique relational dispositions: attachment and rejection sensitivity.

Attachment

In a set of three different volumes, John Bowlby (1969, 1983, 1980) theorized that humans were born with a set of inherent behaviors designed to allow proximity with supportive others. These behaviors were called attachment behaviors, and the supportive others were called attachment figures. Inherent in Bowlby’s model of attachment is that humans have a biological drive to attach themselves with others. For example, a baby’s crying and searching help the baby find their attachment figure (typically a parent/guardian) who can provide care, protection, and support. Infants (and adults) view attachment as an issue of whether an attachment figure is nearby, accessible, and attentive? Bowlby believed that these interpersonal models, which were developed in infancy through thousands of interactions with an attachment figure, would influence an individual’s interpersonal relationships across their entire life span. According to Bowlby, the basic internal working model of affection consists of three components. Infants who bond with their attachment figure during the first two years develop a model that people are trustworthy, develop a model that informs the infant thatthey are valuable, and develop a model that informs the infant that they are effective during interpersonal interactions. As you can easily see, not developing this model during infancy leads to several problems.

If there is a breakdown in an individual’s relationship with their attachment figure (primarily one’s mother), then the infant would suffer long-term negative consequences. Bowlby called his ideas on the importance of mother-child attachment and the lack thereof as the Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis. Bowlby hypothesized that maternal deprivation occurred as a result of separation from or loss of one’s mother or a mother’s inability to develop an attachment with her infant. This attachment is crucial during the first two years of a child’s life. Bowlby predicted that children who were deprived of attachment (or had a sporadic attachment) would later exhibit delinquency, reduced intelligence, increased aggression, depression, and affectionless psychopathy – the inability to show affection or care about others.

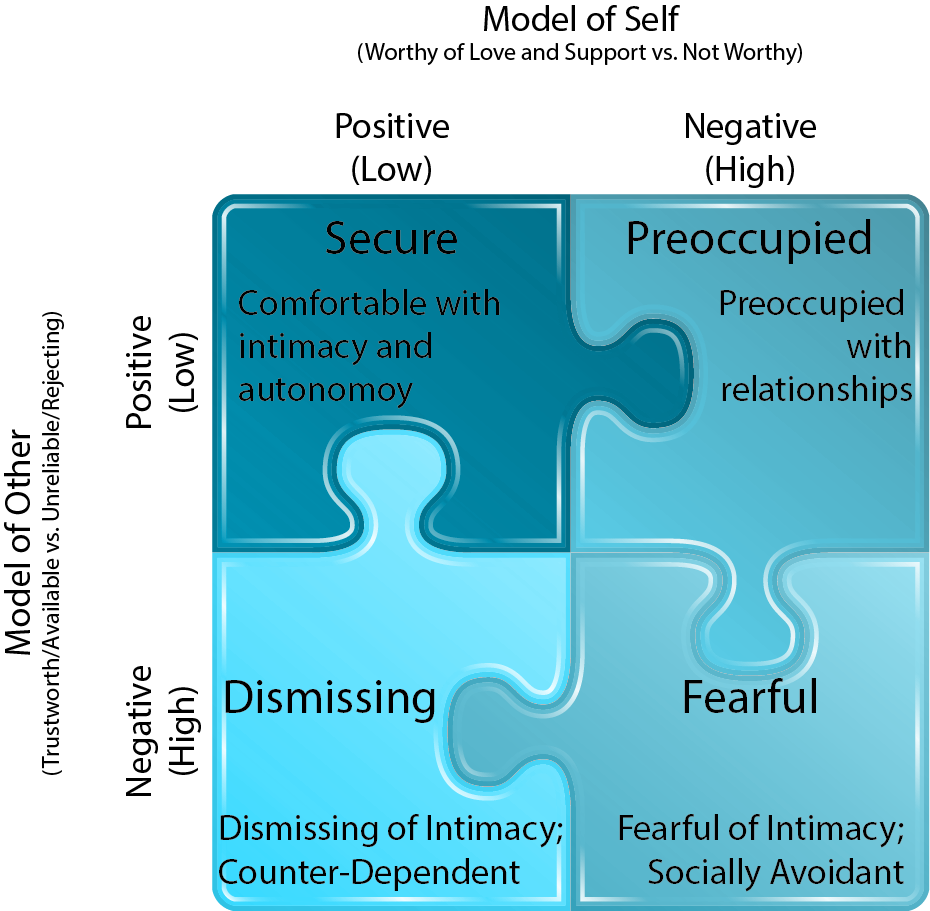

In 1991, Kim Bartholomew and Leonard Horowitz (1991) expanded on Bowlby’s work developing a scheme for understanding adult attachment. In this study, Bartholomew and Horowitz proposed a model for understanding adult attachment. On one end of the spectrum, you have an individual’s abstract image of themself as being either worthy of love and support or not. On the other end of the spectrum, you have an individual’s perception of whether or not another person will be trustworthy/available or another person is unreliable and rejecting. When you combine these dichotomies, you end up with four distinct attachment styles (as seen in Figure 10.5).

The first attachment style is labeled “secure,” because these individuals believe that they are loveable and expect that others will generally behave in accepting and responsive ways within interpersonal interactions. Not surprisingly, secure individuals tend to show the most satisfaction, commitment, and trust in their relationships.

The second attachment style, preoccupied, occurs when someone does not perceive themself as worthy of love but does generally see people as trustworthy and available for interpersonal relationships. These individuals would attempt to get others to accept them.

The third attachment style, fearful (sometimes referred to as fearful avoidants), represents individuals who see themselves as unworthy of love and generally believe that others will react negatively through either deception or rejection (Guerro & Brugoon, 1996). These individuals simply avoid interpersonal relationships to avoid being rejected by others. Even in communication, fearful people may avoid communication because they simply believe that others will not provide helpful information or others will simply reject their communicative attempts.

The final attachment style, dismissing, reflects those individuals who see themselves as worthy of love, but generally believes that others will be deceptive and reject them in interpersonal relationships. These people tend to avoid interpersonal relationships to protect themselves against disappointment that occurs from placing too much trust in another person or making one’s self vulnerable to rejection.

Rejection Sensitivity

Although no one likes to be rejected by other people in interpersonal interactions, most of us do differ from one another in how this rejection affects us as humans. We’ve all had our relational approaches (either by potential friends or dating partners) rejected at some point and know that it kind of sucks to be rejected. The idea that people differ in terms of degree in how sensitive they are to rejection was first discussed in the 1930s by a German psychoanalyst named Karen Horney (1937). Rejection sensitivity can be defined as the degree to which an individual expects to be rejected, readily perceives rejection when occurring, and experiences an intensely adverse reaction to that rejection.

First, people that are highly sensitive to rejection expect that others will reject them. This expectation of rejection is generally based on a multitude of previous experiences where the individual has faced real rejection. Hence, they just assume that others will reject them.

Second, people highly sensitive to rejection are more adept at noting when they are being rejected; however, it’s not uncommon for these individuals to see rejection when it does not exist. Horney explains perceptions of rejection in this fashion:

It is difficult to describe the degree of their sensitivity to rejection. Change in an appointment, having to wait, failure to receive an immediate response, disagreement with their opinions, any noncompliance with their wishes, in short, any failure to fulfill their demands on their terms, is felt as a rebuff. And a rebuff not only throws them back on their basic anxiety, but it is also considered equivalent to humiliation (Horney, 1937, p. 135).

As we can see from this short description from Horney, rejection sensitivity can occur from even the slightest perceptions of being rejected.

Lastly, individuals who are highly sensitive to rejection tend to react negatively when they feel they are being rejected. This negative reaction can be as simple as just not bothering to engage in future interactions or even physical or verbal aggression. The link between the rejection and the negative reaction may not even be completely understandable to the individual. Horney (1937) explains, “More often the connection between feeling rebuffed and feeling irritated remains unconscious. This happens all the more easily since the rebuff may have been so slight as to escape conscious awareness. Then a person will feel irritable, or become spiteful and vindictive or feel fatigued or depressed or have a headache, without the remotest suspicion why” (p. 136). Ultimately, individuals with high sensitivity to rejection can develop a “why bother” approach to initiating new relationships with others. This fear of rejection eventually becomes a self-induced handicap that prevents these individuals from receiving the affection they desire.

As with most psychological phenomena, this process tends to proceed through a series of stages. Horney explains that individuals suffering from rejection sensitivity tend to undergo an eight-step cycle:

- Fear of being rejected.

- Excessive need for affection (e.g., demands for exclusive and unconditional love).

- When the need is not met, they feel rejected.

- The individual reacts negatively (e.g., with hostility) to the rejection.

- Repressed hostility for fear of losing the affection.

- Unexpressed rage builds up inside.

- Increased fear of rejection.

- Increased need for relational reassurance from a partner.

Of course, as an individual’s need for relational reassurance increases, so does their fear of being rejected, and the perceptions of rejection spiral out of control. Research by Towler and Stuhamker (2012) suggests that attachment styles can also impact the quality of relationships between individuals in the workplace.

As you may have guessed, there is a strong connection between John Bowlby’s (1969, 1973, 1980) attachment theory and Karen Horney’s (1937) theory of rejection sensitivity. As you can imagine, rejection sensitivity has several implications for interpersonal communication. In a study conducted by Downey et al. (1998), the researchers wanted to track high versus low rejection sensitive individuals in relationships and how long those relationships lasted. The researchers also had the participants complete the Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire created by Geraldine Downey and Scott Feldman (1996). The study started by having couples keep diaries for four weeks, which helped the researchers develop a baseline perception of an individual’s sensitivity to rejection during the conflict. After the initial four-week period, the researchers revisited the participants one year later to see what had happened. Not surprisingly, high rejection sensitive individuals were more likely to break up during the study than their low rejection sensitivity counterparts. More recently Dorfman et al. (2020) found that high rejection sensitivity impacted reasoning ability during conflict at work.

Adapted Works

“Intrapersonal Communication” in Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 61(2), 226-244. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226

Beatty, M. J., & McCroskey, J. C., & Valencic, K. M. (2001). The biology of communication: A communibiological perspective. Hampton Press.

Bem, S. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036215

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss (Vol. 1: Attachment). Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss (Vol. 2: Separation). Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (I980). Attachment and loss (Vol. 3: Loss, sadness and depression). Basic Books.

Buss, A. (2009). Anxious and self-conscious shyness. In J. A. Daly, J. C. McCroskey, J. Ayers, T. Hopf, D. M. Ayres Sonandre, & T. K. Wongprasert (Eds.), Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication apprehension (3rd ed., pp. 129-148). Hampton Press.

Colby, N., Hopf, T., & Ayers, J. (1993). Nice to meet you? Inter/intrapersonal perceptions of communication apprehension in initial interactions. Communication Quarterly, 41(2), 221-230. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379309369881

Daly, J. A. (2011). Personality and interpersonal communication. In M. L. Knapp & J. A. Daly (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interpersonal communication (4th ed., pp. 131-167). Sage.

Dorfman, A., Oakes, H., & Grossmann, I. (2020). Rejection sensitivity hurts your open mind: Rejection sensitivity and wisdom in workplace conflicts. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2020, No. 1, p. 20479). Academy of Management.

Downey, G., & Feldman, S. I. (1996). Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1327-1343. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1327

Downey, G., Freitas, A. L., Michaelis, B., & Khouri, H. (1998). The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: Rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(2), 545-560. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.545

Horney, K. (1937). The neurotic personality of our time. W. W. Norton and Company.

Infante, D. A., & Rancer, A. S. (1982). A conceptualization and measure of argumentativeness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 46(1), 72-80. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4601_13

Infante, D. A., & Wigley, C. J. (1986). Verbal aggressiveness: An interpersonal model and measure. Communication Monographs, 53(1), 61-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758609376126

Kinney, T. A. (1994). An inductively derived typology of verbal aggression and its relationship to distress. Human Communication Research, 21(2), 183-222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1994.tb00345.x

Martin, M. M., Anderson, C. M., & Horvath, C. L. (1996). Feelings about verbal aggression: Justifications for sending and hurt from receiving verbally aggressive messages. Communication Research Reports, 13(1), 19-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824099609362066

McCroskey, J. C. (1977). Classroom consequences of communication apprehension. Communication Education, 26(1), 27-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634527709378196

McCroskey, J. C. (1982). An introduction to rhetorical communication (4th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1982). Communication apprehension and shyness: Conceptual and operational distinctions. Central States Speech Journal, 33, 458-468.

McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1987). Willingness to communicate. In J. C. McCroskey & J. A. Daly (Eds.), Personality and interpersonal communication (pp. 129-156). Sage.

McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1996). Fundamentals of human communication: An interpersonal perspective. Waveland Press.

Myers, S. A., & Johnson, A. D. (2003). Verbal aggression and liking in interpersonal relationships. Communication Research Reports, 20(1), 90-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090309388803

Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85-101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Neff, K., & Germer, C. (2018). The mindful self-compassion workbook: A proven way to accept yourself, build inner strength, and thrive. Guilford.

Patterson, B. R., & Beckett, C. (1995). A re-examination of relational repair and reconciliation: Impact of socio-communicative style on strategy selection. Communication Research Reports, 12(2), 235–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824099509362061

Richmond, V. P., & Martin, M. M. (1998). Sociocommunicative style and sociocommunicative orientation. In J. C. McCroskey, J. A. Daly, M. M. Martin, & M. J. Beatty (Eds.), Communication and personality: Trait perspectives (pp. 133-148). Hampton Press.

Richmond, V. P., & McCroskey, J. C. (1985). Communication apprehension, avoidance, and effectiveness. Gorsuch Scarisbrick.

Richmond, V. P., & McCroskey, J. C. (1990). Reliability and separation of factors on the assertiveness-responsiveness measure. Psychological Reports, 67(2), 449–450. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.67.6.449-450

Richmond, V. P., Wrench, J. S., & McCroskey, J. C. (2013). Communication apprehension, avoidance, and effectiveness (6th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Richmond, V. P., Wrench, J. S., & McCroskey, J. C. (2018). Scared speechless: Communication apprehension, avoidance, and effectiveness (7th ed.). Kendall-Hunt.

Semic, B. A., & Canary, D. J. (1997). Trait argumentativeness, verbal aggressiveness, and minimally rational argument: An observational analysis of friendship discussions. Communication Quarterly, 45(4), 354-378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379709370071

Towler, A. J., & Stuhlmacher, A. F. (2012). Attachment styles, relationship satisfaction, and well-being in working women. The Journal of Social Psychology, 153(3), p. 279-298.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1977). Shyness: What it is, what to do about it. Addison-Wesley.