4.1 Power

In this section:

Power

We’ll look at the aspects and nuances of power in more detail in this chapter, but to begin, we will define power as follows:

In other words, power involves one person changing the behavior of another. It is important to note that in most organizational situations, we are talking about implied force to comply, not necessarily actual force. That is, person A has power over person B if person B believes that person A can, in fact, force person B to comply.

Power distribution is usually visible within organizations. For example, Salancik and Pfeffer (1989) gathered information from a company with 21 department managers and asked 10 of those department heads to rank all the managers according to the influence each person had in the organization. Although ranking 21 managers might seem like a difficult task, all the managers were immediately able to create that list. When Salancik and Pfeffer compared the rankings, they found virtually no disagreement in how the top 5 and bottom 5 managers were ranked. The only slight differences came from individuals ranking themselves higher than their colleagues ranked them. The same findings held true for factories, banks, and universities.

Power, Authority, and Leadership

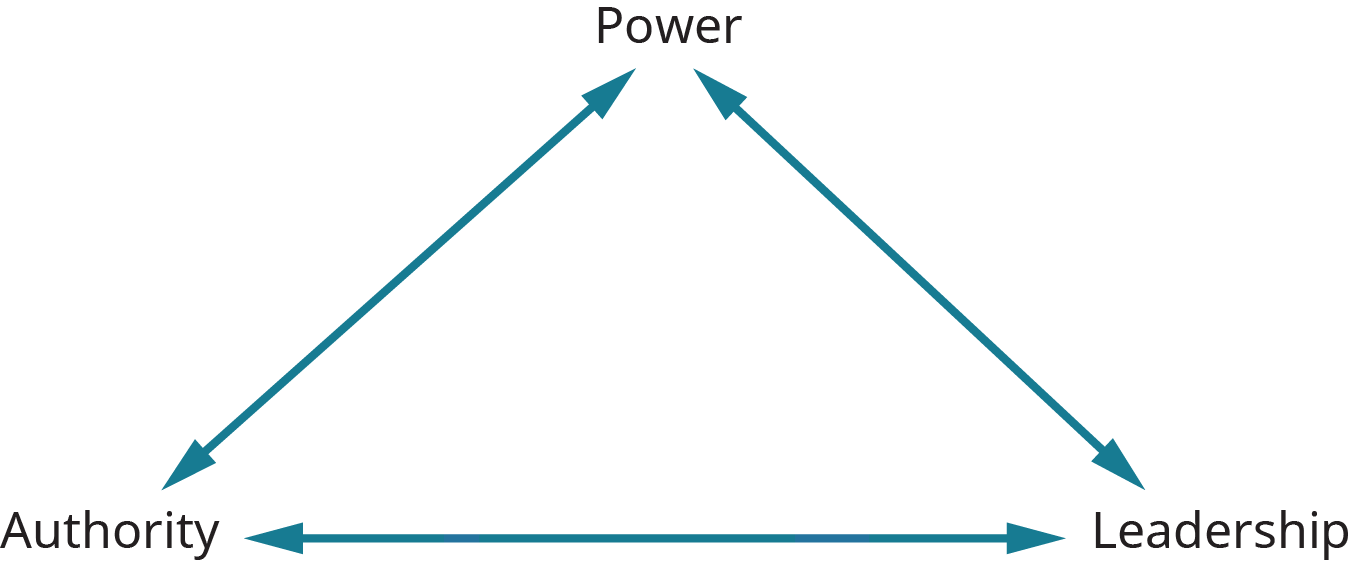

Clearly, the concept of power is closely related to the concepts of authority and leadership (see Figure 4.1 below). In fact, power has been referred to by some as “informal authority,” whereas authority has been called “legitimate power.” However, these three concepts are not the same, and important differences among the three should be noted (Mintzberg, 1983; House, 1988).

As stated previously, power represents the capacity of one person or group to secure compliance from another person or group. Nothing is said here about the right to secure compliance—only the ability. In contrast, authority represents the right to seek compliance by others; the exercise of authority is backed by legitimacy. If a manager instructs an employee to complete a task that is a part of their assigned duties, they presumably have the authority to make such a request. However, if the same manager asked the employee to run personal errands, this would be outside the bounds of the legitimate exercise of authority. Although the employee may still act on this request, this compliance would be based on power or influence considerations, not authority.

Hence, the exercise of authority is based on group acceptance of someone’s right to exercise legitimate control. As Grimes notes, “What legitimates authority is the promotion or pursuit of collective goals that are associated with group consensus. The polar opposite, power, is the pursuit of individual or particularistic goals associated with group compliance” (Grimes, 1978, p. 726)

Finally, leadership is the ability of one individual to elicit responses from another person that go beyond required or mechanical compliance. It is this voluntary aspect of leadership that sets it apart from power and authority. Hence, we often differentiate between headship and leadership. A department head may have the right to require certain actions, whereas a leader has the ability to inspire certain actions. Although both functions may be served by the same individual, such is clearly not always the case.

Krista’s Book Club Recommendation: Gentle Power

In her 2023 book Gentle Power: A Revolution in How We Think, Lead and Succeed Using the Finnish Art of Sisu, Dr. Emilia Elisabeth Lahti offers suggestions about how to balance power with compassion. Lahti describes her approach: “Sisu is a Finnish word for determination and inner fortitude in the face of extreme adversity. Gentle power is to apply sisu with wisdom and heart.”

In her 2023 book Gentle Power: A Revolution in How We Think, Lead and Succeed Using the Finnish Art of Sisu, Dr. Emilia Elisabeth Lahti offers suggestions about how to balance power with compassion. Lahti describes her approach: “Sisu is a Finnish word for determination and inner fortitude in the face of extreme adversity. Gentle power is to apply sisu with wisdom and heart.”

Lahti notes that this model of gentle power is helpful for everyone – not just high-power executives. This book also touches on the self and the importance of self-care. If you’ve struggled with discomfort around exercising power because the idea is integrally tied to toxic dominance and aggression, this book might be helpful in helping you think about your own power in a different way.

Students may also be interested in her TEDx Talk introducing the concept of Sisu.

References

Lahti, E. E. (2023). Home. https://www.sisulab.com/

Lahti, E. E. (2023). Gentle power is in the bookstores. https://www.sisulab.com/my-work

Lahti. E. E. (2014). Sisu – Transforming barriers into frontiers. TEDxTurku. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UTIizGyf5kU

Symbols of Managerial Power

How do we know when a manager has power in an organizational setting? Harvard professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter (2004) has identified several of the more common symbols of managerial power. For example, managers have power to the extent that they can intercede favorably on behalf of someone in trouble with the organization. Have you ever noticed that when several people commit the same mistake, some don’t get punished? Perhaps someone is watching over them.

Moreover, managers have power when they can get a desirable placement for a talented subordinate or get approval for expenditures beyond their budget. Other manifestations of power include the ability to secure above-average salary increases for subordinates and the ability to get items on the agenda at policy meetings.

And we can see the extent of managerial power when someone can gain quick access to top decision makers or can get early information about decisions and policy shifts. In other words, who can get through to the boss, and who cannot? Who is “connected,” and who is not?

Finally, power is evident when top decision makers seek out the opinions of a particular manager on important questions. Who gets invited to important meetings, and who does not? Who does the boss say “hello” to when they enter the room? Through such actions, the organization sends clear signals concerning who has power and who does not. In this way, the organization reinforces or at least condones the power structure in existence.

Relationship Between Dependency and Power

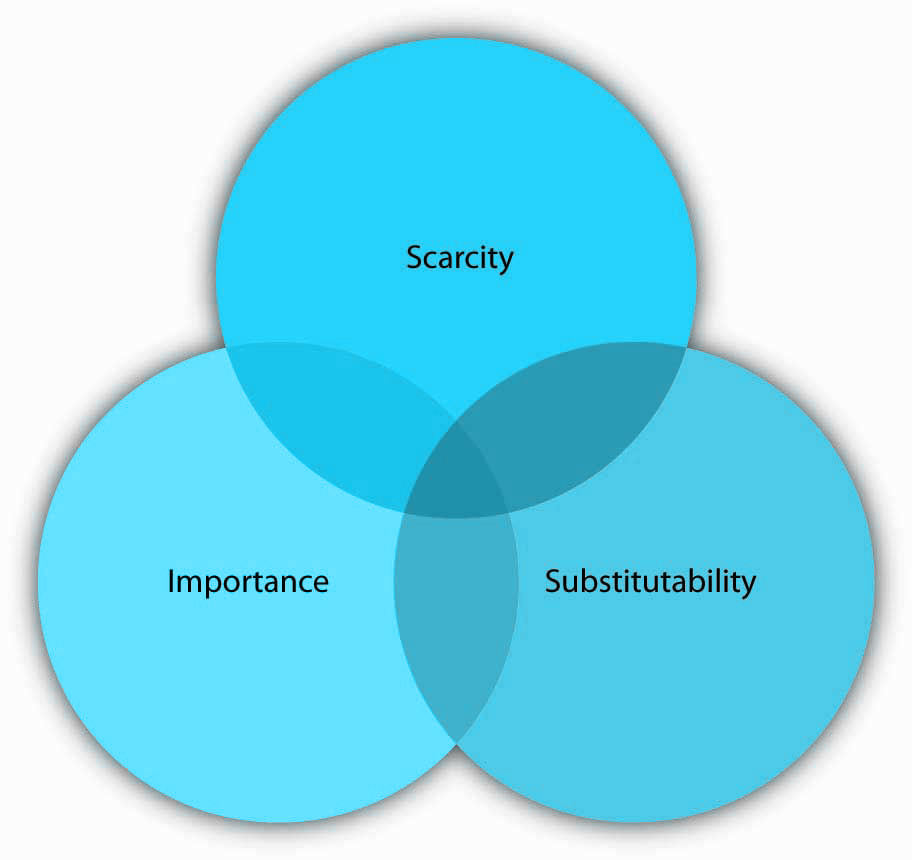

Dependency is directly related to power. The more that a person or unit is dependent on you, the more power you have. The strategic contingencies model provides a good description of how dependency works. According to the model, dependency is power that a person or unit gains from their ability to handle actual or potential problems facing the organization (Saunders, 1990). You know how dependent you are on someone when you answer three key questions surrounding scarcity, importance, and substitutability. Let’s learn more about each of these criteria.

Scarcity

Recall back to our definition of conflict in Chapter 1. Scarcity (actual or perceived) is often involved in conflict. In the context of dependency, scarcity refers to the uniqueness of a resource. The more difficult something is to obtain, the more valuable it tends to be. Effective persuaders exploit this reality by making an opportunity or offer seem more attractive because it is limited or exclusive. They might convince you to take on a project because “it’s rare to get a chance to work on a new project like this,” or “You have to sign on today because if you don’t, I have to offer it to someone else.”

Importance

Importance refers to the value of the resource. The key question here is “How important is this?” If the resources or skills you control are vital to the organization, you will gain some power. Think back to our discussion of negotiation. The more vital the resources that you control are, the more power you will have. For example, if Kecia is the only person who knows how to fill out reimbursement forms, it is beneficial that you are able to work with her, if you place importance on getting your personal expense reports processed in a timely fashion.

Substitutability

Finally, substitutability refers to one’s ability to find another option that works as well as the one offered. The question around whether something is substitutable is “How difficult would it be for me to find another way to this?” The harder it is to find a substitute, the more dependent the person becomes and the more power someone else has over them. If you are the only person who knows how to make a piece of equipment work, you will be very powerful in the organization. This is true unless another piece of equipment is brought in to serve the same function. At that point, your power would diminish. Similarly, countries with large supplies of crude oil have traditionally had power to the extent that other countries need oil to function.

Bases of Power

Having power and using power are two different things. What are the sources of one’s power over others? Researchers identified six sources of power, which include legitimate, reward, coercive, expert, information, and referent (French & Raven, 1960).

Legitimate Power

Legitimate power is power that comes from one’s organizational role or position. It is synonymous with authority. For example, a manager can assign projects, a police officer can arrest a citizen, and a teacher assigns grades. Others comply with the requests these individuals make because they accept the legitimacy of the position, whether they like or agree with the request or not.

Legitimate power derives from three sources. First, prevailing cultural value, accepted social structures, and designation are all ways that power can be assigned to a group. Whatever the reason, people exercise legitimate power because others assume they have a right to exercise it.

Reward Power

Reward power is the ability to grant a reward, such as an increase in pay, a perk, or an attractive job assignment. Reward power tends to accompany legitimate power and is highest when the reward is scarce. Anyone can wield reward power, however, in the form of public praise or giving someone something in exchange for their compliance.

Coercive Power

Coercive power is the ability to take something away or punish someone for noncompliance. Coercive power often works through fear, and it forces people to do something that ordinarily they would not choose to do. The most extreme example of coercion is government dictators who threaten physical harm for noncompliance.

As Kipnis (1976) points out, coercive power does not have to rest on the threat of violence. “Individuals exercise coercive power through a reliance upon physical strength, verbal facility, or the ability to grant or withhold emotional support from others. These bases provide the individual with the means to physically harm, bully, humiliate, or deny love to others.” (p. 77) Examples of coercive power in organizations include the ability (actual or implied) to fire or demote people, transfer them to undesirable jobs or locations, or strip them of valued perquisites. Indeed, it has been suggested that a good deal of organizational behavior (such as prompt attendance, looking busy, avoiding whistle-blowing) can be attributed to coercive power.

Expert Power

Expert power comes from knowledge and skill. In an organization include long-time employees, such as a steelworker who knows the temperature combinations and length of time to get the best yields have expert power. Examples of expert power can be seen in staff specialists in organizations (e.g., accountants, labor relations managers, management consultants, and corporate attorneys). In each case, the individual has credibility in a particular—and narrow—area as a result of experience and expertise, and this gives the individual power in that domain.

Information Power

Information power is similar to expert power but differs in its source. Experts tend to have a vast amount of knowledge or skill, whereas information power is distinguished by access to specific information. For example, knowing price information gives a person information power during negotiations. Within organizations, a person’s social network can either isolate them from information power or serve to create it. Individuals who are able to span boundaries and serve to connect different parts of the organizations often have a great deal of information power.

Consider This: Authority & Knowledge Hierarchies

When discussing power, authority, and status, and who holds it in organizational and other contexts, it is worthwhile considering knowledge hierarchies or epistemological status, or, in other words, the ways we ascribe credibility/authority to certain knowledge claims above others (do Mar Pereira, 2017).

When discussing power, authority, and status, and who holds it in organizational and other contexts, it is worthwhile considering knowledge hierarchies or epistemological status, or, in other words, the ways we ascribe credibility/authority to certain knowledge claims above others (do Mar Pereira, 2017).

For example, consider the ways knowledge is created and privileged in academic spaces. Positivist approaches, such as what is often seen in the ‘hard sciences’ (using quantitative methods, deduction, and experimentation), are generally positioned as objective (Park et al., 2020; Rehman & Alharthi, 2016) compared with interpretivist approaches, which use tend to rely on more inductive approaches and acknowledge and value subjectivities (Rechberg, 2018; Rehman & Alharthi, 2016). Moreover, in many academic/institutional spaces, Western scientific/positivist approaches are often valued and prioritized above interpretivist or other approaches (e.g. see Althaus, 2020); this can be evident in subtle and overt ways, such as in relative funding opportunities, prestige, and other outcomes attached to the respective paradigms (e.g. see Anderson, 1995). These domains or approaches represent distinct ways of viewing and doing things based around certain sets of assumptions. Moreover, knowledge hierarchies can also occur along disciplinary, gendered (e.g. see Anderson, 1995), and cultural boundaries (e.g. see Althaus, 2020).

Likewise, in many contexts, Western (and colonial) paradigms often shape the way many institutions run (i.e. policies, administration, etc.) (Althaus, 2020). Because of the implicit assumptions and biases within such knowledge claims, this can be a barrier to engagement, equity, and inclusion, as well as a precipitating factor for conflict situations across various levels of conflict. However, more recently, with greater attention given to equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) initiatives, knowledge systems and approaches (e.g. Indigenous ways of knowing) that extend beyond the Western models are being valued for their unique and important contributions (Althaus, 2020; see also Bowers, 2012). Increased collaboration and honouring of holistic and relational approaches and other Indigenous models could have notable implications for a broad array of organizational spaces, systems, and skills, including in the areas of intercultural competence, communication, and conflict management/resolution (Althaus, 2020; Duggan et al., 2013; see also Bowers, 2012) and can support some of the 94 Calls to Action in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (TRCC, 2015).

Questions to Consider

- What knowledge claims are prioritized in the spaces you inhabit?

- How do you know?

- Who benefits from this? Who doesn’t?

Further, understanding knowledge hierarchies and epistemological status also 1) enables critical thinking, 2) cultivates self-awareness of the self and others within broader systems, 3) challenges assumptions and norms within institutional/organizational practices, and 4) creates space for us to move beyond the traditional levels to consider greater complexity and understandings of power and status, particularly within organizational/institutional spaces.

References:

Althaus, C. (2020). Different paradigms of evidence and knowledge: recognizing, honouring, and celebrating indigenous ways of knowing and being. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 79(2), 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12400

Anderson, E. (1995). Feminist epistemology: An interpretation and a defence. Hypatia, 10(3), 50–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3810237

Bowers, K. S. P. R. (2012). From little things, big things grow, from big things little things manifest: an indigenous human ecology discussing issues of conflict, peace and relational sustainability. Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 8(3), 290–304.

do Mar Pereira, M. (2017). Power, knowledge and feminist scholarship. Routledge. Taylor and Francis Group.

Duggan, G. L., Green, L. J. F., Rogerson, J. J. M., & Jarre, A. (2014). Opening dialogue and fostering collaboration: different ways of knowing in fisheries research: research article. South African Journal of Science, 110(7), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2014/20130128

Park, Y., Konge, L., & Artino, A. R. (2020). The positivism paradigm of research. Academic medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 95(5). http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ ACM.0000000000003093

Rechberg, I. D. W. (2018). Knowledge management paradigms, philosophical assumptions: An outlook on future research. American Journal of Management, 8(3), 61-74.

Rehman, A. A. & Alharthi, K. (2016). An introduction to research paradigms. International Journal of Educational Investigations, 3(8), 51-59. http://www.ijeionline.com/attachments/article/57/IJEI.Vol.3.No.8.05.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/2091412-trc-calls-to-action.html

Referent Power

Referent power stems from the personal characteristics of the person such as the degree to which we like, respect, and want to be like them. Referent power is often called charisma—the ability to attract others, win their admiration, and hold them spellbound. In work environments, junior managers often emulate senior managers and assume unnecessarily subservient roles more because of personal admiration than because of respect for authority.

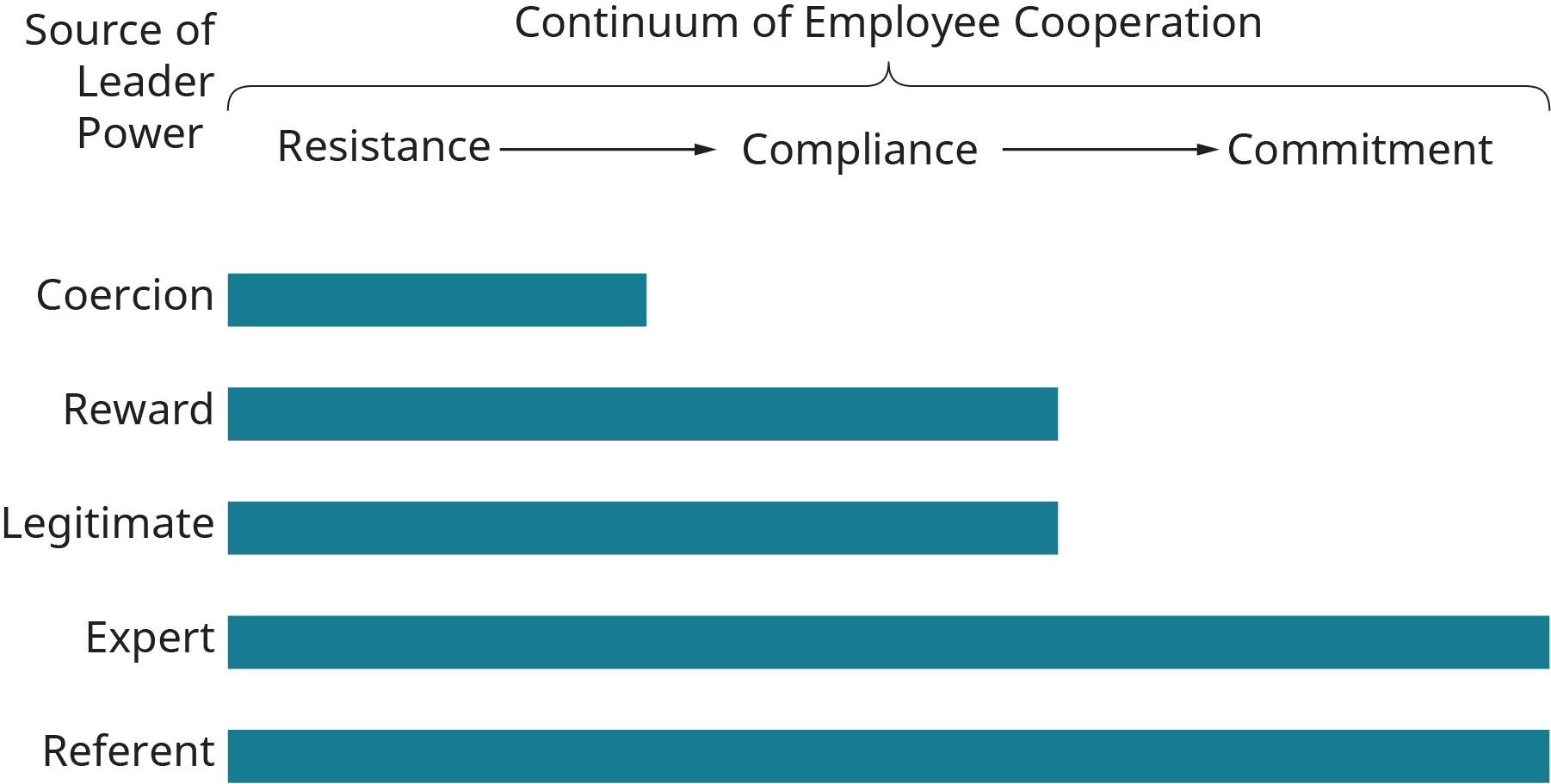

Consequences of Power

We have seen, then, that at least six bases of power can be identified. In each case, the power of the individual rests on a particular attribute of the power holder, the follower, or their relationship. In some cases (e.g., reward power), power rests in the superior; in others (e.g., referent power), power is given to the superior by the subordinate. In all cases, the exercise of power involves subtle and sometimes threatening interpersonal consequences for the parties involved. In fact, when power is exercised, employees have several ways in which to respond. These are shown in Figure 4.3.

If the subordinate accepts and identifies with the leader, his behavioral response will probably be one of commitment. That is, the subordinate will be motivated to follow the wishes of the leader. This is most likely to happen when the person in charge uses referent or expert power. Under these circumstances, the follower believes in the leader’s cause and will exert considerable energies to help the leader succeed.

A second possible response is compliance. This occurs most frequently when the subordinate feels the leader has either legitimate power or reward power. Under such circumstances, the follower will comply, either because it is perceived as a duty or because a reward is expected; but commitment or enthusiasm for the project is lacking.

Finally, under conditions of coercive power, subordinates will more than likely use resistance. Here, the subordinate sees little reason—either altruistic or material—for cooperating and will often engage in a series of tactics to defeat the leader’s efforts.

Positive and Negative Consequences of Power

Power has both positive and negative consequences. On one hand, powerful CEOs can align an entire organization to move together to achieve goals. Amazing philanthropists such as Paul Farmer, a doctor who brought hospitals, medicine, and doctors to remote Haiti, and Greg Mortenson, a mountaineer who founded the Central Asia Institute and built schools across Pakistan, draw on their own power to organize others toward lofty goals; they have changed the lives of thousands of individuals in countries around the world for the better (Kidder, 2004: Mortenson & Relin, 2006). On the other hand, autocracy can destroy companies and countries alike. The phrase, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” was first said by English historian John Emerich Edward Dalberg, who warned that power was inherently evil and its holders were not to be trusted. History shows that power can be intoxicating and can be devastating when abused. One reason that power can be so easily abused is because individuals are often quick to conform.

Common Power Tactics in Organizations

Here, we look at some of the more commonly used power tactics found in both business and public organizations (Pfeffer, 2011).

Controlling Access to Information

Most decisions rest on the availability of relevant information, so persons controlling access to information play a major role in decisions made. A good example of this is the common corporate practice of pay secrecy. Only the personnel department and senior managers typically have salary information—and power—for personnel decisions.

Controlling Access to Persons

Another related power tactic is the practice of controlling access to persons. This can lead to isolation, especially of individuals in upper levels of organizational hierarchy.

Selective Use of Objective Criteria

Very few organizational questions have one correct answer; instead, decisions must be made concerning the most appropriate criteria for evaluating results. As such, significant power can be exercised by those who can practice selective use of objective criteria that will lead to a decision favorable to themselves. According to Herbert Simon, if an individual is permitted to select decision criteria, they needn’t care who actually makes the decision. Attempts to control objective decision criteria can be seen in faculty debates in a university or college over who gets hired or promoted. One group tends to emphasize teaching and will attempt to set criteria for employment dealing with teacher competence, subject area, interpersonal relations, and so on. Another group may emphasize research and will try to set criteria related to number of publications, reputation in the field, and so on.

Controlling the Agenda

One of the simplest ways to influence a decision is to ensure that it never comes up for consideration in the first place. There are a variety of strategies used for controlling the agenda. Efforts may be made to order the topics at a meeting in such a way that the undesired topic is last on the list. Failing this, opponents may raise a number of objections or points of information concerning the topic that cannot be easily answered, thereby tabling the topic until another day.

Using Outside Experts

Still another means to gain an advantage is using outside experts. The unit wishing to exercise power may take the initiative and bring in experts from the field or experts known to be in sympathy with their cause. Hence, when a dispute arises over spending more money on research versus actual production, we would expect differing answers from outside research consultants and outside production consultants. Most consultants have experienced situations in which their clients fed them information and biases they hoped the consultant would repeat in a meeting.

Bureaucratic Gamesmanship

In some situations, the organizations own policies and procedures provide ammunition for power plays, or bureaucratic gamesmanship. For instance, a group may drag its feet on making changes in the workplace by creating red tape, work slowdowns, or “work to rule.” (Working to rule occurs when employees diligently follow every work rule and policy statement to the letter; this typically results in the organization’s grinding to a halt as a result of the many and often conflicting rules and policy statements.) In this way, the group lets it be known that the workflow will continue to slow down until they get their way.

Coalitions and Alliances

The final power tactic to be discussed here is that of coalitions and alliances. One unit can effectively increase its power by forming an alliance with other groups that share similar interests. This technique is often used when multiple labor unions in the same corporation join forces to gain contract concessions for their workers. It can also be seen in the tendency of corporations within one industry to form trade associations to lobby for their position. Although the various members of a coalition need not agree on everything—indeed, they may be competitors—sufficient agreement on the problem under consideration is necessary as a basis for action.

Although other power tactics could be discussed, these examples serve to illustrate the diversity of techniques available to those interested in acquiring and exercising power in organizational situations.

Recourse for Conflict Within a Power Differential?

Various conflict prevention, reduction, management, and resolution strategies are discussed throughout the textbook, including many that may still be relevant despite the power differential. Still, power dynamics can pose additional challenges, for instance, when one party is disproportionately impacted by the conflict and they are disempowered because of a power hierarchy/differential. If the typical strategies prove ineffective and/or the situation is severe (i.e. includes bullying, harassment, or violence), there can be other options, including the following:

- relying on the organizations/institutions own texts, such as policies and procedures, job descriptions, and/or a Collective Agreement

- consulting with the organization’s human resources department, the employee union, or the EDI office (where relevant)

Sometimes, institutional policies and practices create and/or enable problematic hierarchies. In this case, it can be useful or sometimes even necessary to find support outside of the organization. For example, leaning on more authoritative texts might be helpful:

- Occupational Health and Safety Act

- Public Services Health & Safety Association

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety

- Ontario Human Rights Commission

Seeking legal counsel (independent of the organization) can be another option; nonetheless, as Ahmed (2021) states, “complaints have consequences” (p. 272). Sometimes the situation improves, sometimes it stays the same, and sometimes it gets worse (and sometimes it gets worse before it gets better). The outcomes can be complex and dependent on numerous factors. Ahmed also discusses the notion of collective complaints to share experiences and to increase the weight of the complaint.

Whistleblowing can offer recourse in some situations. Whistleblowing is defined as “disclosure by organization members (former or current) of illegal, immoral or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to effect action” (Micelli & Near, 1984). Roberts et al. (2011) wrote a guide for public sector organizations to set up systems and procedures for dealing with public interest whistleblowing. Additionally, the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada (2016) commissioned a report discussing the very real fear of reprisal that can exist alongside whistleblowing, in addition to evidence-informed strategies that organizations can adopt to increase safety for those exposing wrongdoing. Still, good resources for individuals who are considering whistleblowing in ways that minimize personal risk are harder to come by.

Krista’s Book Club Recommendation: Complaint!

Ahmed’s (2021) Complaint! explores circumstances and outcomes of complaints against harassment, bullying, violence, and other uses and abuses of power in institutional contexts (particularly in post-secondary academic institutions). Ahmed shares lived experiences from students and faculty about the power imbalances that occur and the outcomes of complaints. This book highlights the costs of raising a complaint, the institutional processes that hide issues under a blanket of confidentiality, and how the policies and procedures within institutions can perpetuate structural violence.

Ahmed’s (2021) Complaint! explores circumstances and outcomes of complaints against harassment, bullying, violence, and other uses and abuses of power in institutional contexts (particularly in post-secondary academic institutions). Ahmed shares lived experiences from students and faculty about the power imbalances that occur and the outcomes of complaints. This book highlights the costs of raising a complaint, the institutional processes that hide issues under a blanket of confidentiality, and how the policies and procedures within institutions can perpetuate structural violence.

References

Ahmed, S. (2021). Complaint! Duke University Press.

Case Study

Adapted Works

Ahmed, S. (2021). Complaint!. Duke University Press.

“Organizational Power and Politics” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

“Power and Politics” in Organizational Behaviour by Saylor Academy is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

Reference

French, J. P. R., Jr., & Raven, B. (1960). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright & A. Zander (Eds.), Group dynamics (pp. 607–623). Harper and Row.

Grimes, A. (1978). Authority, power, influence, and social control: A theoretical synthesis. Academy of Management Review, 3(4), 724-735.

House, R. J. (1988). Power and personality in complex organizations. In B. M. Staw and L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 307-357). JAI Press.

Kanter, R. (2004). On the frontiers of management. Harvard Business Review Books.

Kidder, T. (2004). Mountains beyond mountains: The quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, a man who would cure the world. Random House.

Kipnis, D. (1976). The powerholders. University of Chicago Press.

Mintzberg, M. (1983). Power in and around organizations. Prentice Hall.

Mortenson, G., & Relin, D. O. (2006). Three cups of tea: One man’s mission to promote peace…One school at a time. Viking.

Near, J. P. & Miceli, M. P. (1985). Organizational dissidence: The case of whistle-blowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 4(1), 1-16.

Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada. (2016, December 22). The sound of silence: Whistleblowing and the fear of reprisal. https://psic-ispc.gc.ca/en/resources/corporate-publications/sound-silence#3

Pfeffer, J. (2011). Power: Why some people have it and others don’t. Harper Business.

Roberts, P., Brown, A. J., & Olsen, J. (2011). Introduction. In Whistling While They Work: A good-practice guide for managing internal reporting of wrongdoing in public sector organizations (pp. 8–16). ANU Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt24hcvb.5

Salancik, G., & Pfeffer, J. (1989). Who gets power. In M. Thushman, C. O’Reily, & D. Nadler (Eds.), Management of organizations. Harper & Row.

Saunders, C. (1990, January). The strategic contingencies theory of power: Multiple perspectives. Journal of Management Studies, 21(1), 1–18.