3.4 Organizational Codes and Discipline

In this section:

Organizational Codes

While culture can be a powerful mechanism of behavioural control within organizations, often these standards are often outlined in company codes. Formalization is the extent to which policies, procedures, job descriptions, and rules are written and explicitly articulated. In other words, formalized structures are those in which there are many written rules and regulations. These structures control employee behavior using written rules, and employees have little autonomy to make decisions on a case-by-case basis. Formalization makes employee behavior more predictable. Whenever a problem at work arises, employees know to turn to a handbook or a procedure guideline. Therefore, employees respond to problems in a similar way across the organization, which leads to consistency of behavior.

Part of managing conflict in the workplace is having clear expectations for employees’ behaviour and methods of recourse if these expectations are not being met. Having codes of conduct, policies and procedures can help all parties to navigate a variety of circumstances including interpersonal conflicts, ethical violations, and instances of workplace incivility like harassment, bullying or discrimination. These policies and procedures should adhere to principles of basic human rights (e.g., the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Ontario Human Rights Code), federal and provincial labour laws, and also conditions in the collective bargaining agreement if one is in place.

Types of Codes

Here are some examples of types of codes that you might encounter within an organization:

- Professional Codes of Ethics. Professions such as engineering and accounting have developed codes of ethics. These set forth the ideals of the profession as well as more mundane challenges faced by members. Engineering codes, for example, set forth service to humanity as an ideal of the profession. But they also provide detailed provisions to help members recognize conflicts of interest, issues of collegiality, and confidentiality responsibilities.

- Corporate Codes of Ethics. Corporate codes are adopted by many companies to provide guidelines on particularly sticky issues (When does a gift become a bribe?) They also set forth provisions that express the core values of the corporation. These lengthy codes with detailed provisions support a compliance approach to organizational discipline.

- Corporate Credos. Some companies have shortened their lengthy codes into a few general provisions that form a creed.

- Statements of Values. Some companies express their core value commitments in Statements of Values. These form the basis of values-based decision-making. While codes of ethics clearly establish minimum standards of acceptable conduct, Statements of Values outline the aspirations that can drive companies toward continuous improvement.

Functions of Codes

Codes and policies can serve a number of functions within the organization including the following:

- Discipline. This function gets all the attention. Most codes are set forth to establish clearly and forcefully an organization’s standards, especially its minimum standards of acceptable conduct. Having established the limits, organizations can then punish those who exceed them.

- Educate. This can range from disseminating standards to enlightening members. Company A’s employees learned that anything over $100 was a bribe and should not be accepted. But engineers learn that their fundamental responsibility is to hold paramount public safety, health, and welfare. Codes certainly teach minimum standards of conduct, but they can help a community to articulate and understand their highest shared values and aspirations.

- Inspirate. Codes can set forth ideals in a way that inspires a community’s members to strive for excellence. They can be written to set forth the aspirations and value commitments that express a community’s ideals. They can point a community toward moral excellence.

- Stimulate Dialogue. Engineering professional codes of ethics have changed greatly over the last 150 years. This has been brought about by a vigorous internal debate stimulated by these very codes. Members debate controversial claims and work to refine more basic statements.

- Empower and Protect. Codes empower and protect those who are committed to doing the right thing. If an employer orders an employee to do something that violates that employee’s ethical or professional standards, the code provides a basis for saying, “No!“. Since codes establish and disseminate moral standards, they can provide the structure to convert personal opinion into reasoned professional judgment. To reiterate, they provide support to those who would do the right thing, even under when there is considerable pressure to do the opposite.

- Codes capture or express a community’s identity. They provide the occasion to identify, foster commitment, and disseminate the values with which an organization wants to be identified publicly. These values enter into an organization’s core beliefs and commitments forming an identify-conferring system. By studying the values embedded in a company’s code of ethics, observing the values actually displayed in the company’s conduct, and looking for inconsistencies, the observer can gain insight into the core commitments of that company. Codes express values that, in turn, reveal a company’s core commitments, or (in the case of a hypocritical organization) those values that have fallen to the wayside as the company has turned to other value pursuits.

Difficulties with Codes

The following objections note some of the difficulties with codes:

- Codes can undermine moral autonomy by habituating us to act from motives like deference to external authority and fear of punishment. We get out of the habit of making decisions for ourselves and fall into the habit of deferring to outside authority.

- Codes often fail to guide us through complex situations. Inevitably, gaps arise between general rules and the specific situations to which they are applied; concrete situations often present new and unexpected challenges that rules, because of their generality, cannot anticipate. Arguing that codes should provide action recipes for all situations neglects the fact that effective moral action requires more than just blind obedience to rules.

- Codes of ethics can encourage a legalistic attitude that turns us away from the pursuit of moral excellence and toward just getting by or staying out of trouble. For example, compliance codes habituate us to striving only to maintain minimum standards of conduct. They fail to motivate and direct action toward aspirations. Relying exclusively on compliance codes conveys the idea that morality is nothing but staying above the moral minimum.

Want to learn more?

Want to learn more?

For best practices in creating and administering codes see this Employer’s Toolkit: Resources for Building an Inclusive Workplace.

Let’s Practice: Exercise On Mission, Vision and Values

Mission Impact on Business Practice and Employee Behavior

Mission Impact on Business Practice and Employee Behavior

In this exercise, you will have an opportunity to explore the way an organization’s mission, vision and values influence their business practices and employee behavior—or not!

Your Task:

- Select a business or organization that you’re familiar with and conduct research to determine their stated mission, vision and values.

- Reflect on your experience with the company/organization. Do the statements ring true or hollow? That is, do their business practices reflect the stated mission, vision and values?

- Next, investigate to see if you can find any codes or policies regarding conflict management, conflict resolution, bullying, harassment, etc.

- Write a brief reflection identifying your selected organization’s mission, vision and values and your opinion on the validity of the statements and policies. Support your position with a specific example based on your personal experience or research. As always, include links to sources cited.

Source: Nina Burokas, Mission Impact on Business Practice and Employee Behavior. Lumen Learning. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

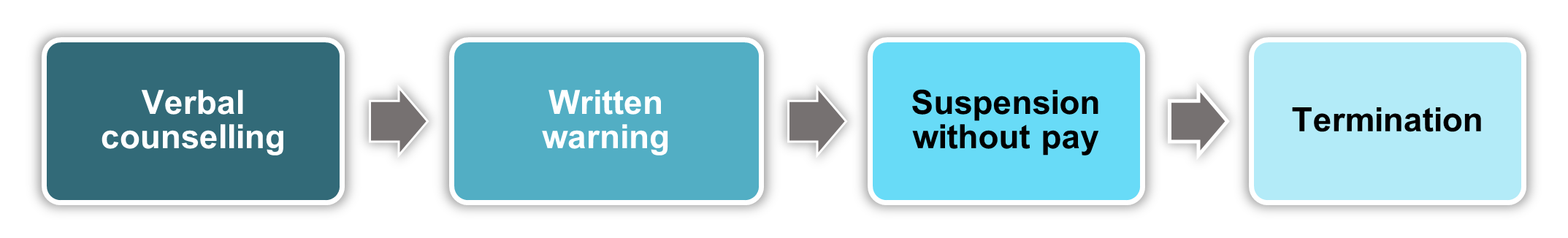

Progressive Discipline

According to Indiana University Organizational Development “Progressive discipline is the process of using increasingly severe steps or measures when an employee fails to correct a problem after being given a reasonable opportunity to do so. The underlying principle of sound progressive discipline is to use the least severe action that you believe is necessary to correct the undesirable situation” (Indiana University Human Resources, n.d.).

There are usually two reasons for disciplining employees: performance problems and misconduct. Misconduct is generally the more serious problem as it is often deliberate, exhibited by acts of defiance. In contrast, poor performance is more often the result of lack of training, skills, or motivation. Performance problems can often be solved through coaching and performance management, while misconduct normally calls for progressive discipline. Sometimes extreme cases of misconduct are grounds for immediate termination.

Consider This: Disciplinary Actions

Examples of Behaviours that May Require Disciplinary Action

Managers often cite the following behaviour when identifying what they perceive to be poor worker performance or misconduct:

- Lack of skills or knowledge

- Lack of motivation

- Poor attitude

- Lack of effort or misconduct (working at a reduced speed, poor quality, tardiness, sleeping on the job, wasting time)

- Poor co-worker relations (arguing on the job, lack of cooperation)

- Poor subordinate-supervisor relations (insubordination, lack of follow-through)

- Inappropriate supervisor-subordinate relations (favouritism, withholding of key information, mistreatment, abuse of power)

- Mishandling company property (misuse of tools, neglect)

- Harassment or workplace violence (verbal or physical abuse, threats, bullying)

- Dishonesty

- Disregard for safety practices (not wearing safety equipment, horseplay, carrying weapons on the job, working under the influence of alcohol or drugs)

Appropriate Level of Discipline

It is important to determine the proper level of discipline in each situation. In other words, “the punishment must fit the crime.” Company policies on discipline should strive for fairness by adhering to these criteria:

- Develop clear, fair rules and consequences.

- Clearly communicate policies.

- Conduct a fair investigation.

- Balance consistency with flexibility.

- Use corrective action, not punishment.

Consistency in discipline is important. How others have been treated for similar infractions should provide the primary basis for determining appropriate action, but there are several factors that may justify increasing or decreasing the level of discipline:

- The employee’s length of service

- Previous record of performance and conduct

- Whether the employee was provoked

- Whether the misconduct was premeditated or a spur-of-the-moment lack of judgment (i.e., was it with or without intent?)

- Whether the employee knew the rules and those rules have been consistently enforced on others

- Whether the employee acknowledges the mistake and shows remorse

After considering all of these factors, there still may be times when you believe it is best for the business to terminate an employee, particularly if you determine that a particular person or situation is likely to be a chronic problem. Paying the required severance, or termination pay, is a small cost compared to the damage a problem employee can cause.

Steps of Progressive Discipline

After each step before termination, the employee should be given an opportunity to correct the problem or behaviour. If he or she fails to do so, the final step is taken: termination.

Step 1: Verbal Counselling

Verbal counselling is usually the initial step. Verbal counselling sessions are used to bring a problem to the attention of the employee before it becomes so serious that it has to become part of a written warning and placed in the employee’s file.

The purpose of the initial discussion is to alleviate misunderstandings and clarify the direction for necessary and successful correction. Most discipline problems can be solved at this stage if the matter is approached constructively and if the employee can be engaged in seeking solutions. This is usually effective because most people don’t want the disciplinary process to escalate.

Consider This: Counselling Session Tips

Below are some tips for conducting a verbal counselling session:

Below are some tips for conducting a verbal counselling session:

- Conduct the counselling session in private. Keep the tone low-key, friendly yet firm.

- Tell the employee the purpose for the discussion. Identify the problems specifically and ensure the employee understands expectations.

- Have documentation available to serve as a basis for the discussion, but try not to read from a list as this might lead the employee to feel defensive.

- Seek input from the employee about his or her perceptions of causes of problems.

- Where possible, identify solutions together. If this is not possible, clearly state your desired solution.

- Be sure the employee understands your expectations; ask them to describe the standard involved and how he or she will behave to correct the problem.

- Let the employee know that possible disciplinary action may follow if the problem is not corrected.

- Ask for a commitment from the employee to resolve the problem.

It isn’t necessary to complete a formal document of the counselling session as it is considered an informal step in progressive discipline. However, you may want to write a brief statement confirming the subject matter discussed and the agreed-upon course of action to correct the problem. This can be a useful reference later if further discipline is needed.

After an appropriate period, be sure to schedule a follow-up meeting with the employee. Provide opportunities for two-way feedback and discussion. Let the employee know how he or she is progressing and ask how the new procedures or behaviours are working.

Step 2: Written Warning

If the problem is not resolved, you will need to prepare the written warning. Include in the warning information, responses, and commitments already made in the verbal counselling session.

The written warning has three parts:

- A statement that the verbal discussion has occurred, which reviewed the employee’s history with respect to the problem. Be sure to include the date the verbal discussion took place.

- A statement about the present, including a description of the current situation and including the employee’s explanation or response. Use the “who, what, when” model to be sure you include all necessary details.

- A statement of the future, describing your expectations and the consequences of continued failure to correct the problem. This step may be repeated in the future with stronger consequence statements, so be clear on what the next step is. For example, this statement might state that the situation “may lead to further disciplinary action” or, in a later warning, “this is a final warning and failure to correct the problem will lead to discharge.”

Consider This: Written Warning

Tips for Creating a Written Warning

Tips for Creating a Written Warning

By documenting these conversations, you cover yourself in legal disputes that may arise from terminations. Here are some guidelines for documenting written warnings:

- Clearly identify the performance issue that needs to be resolved.

- Give the employee the opportunity to propose a solution to the issue with you.

- Agree on the solution, and document what is going to change. Include a section on how the employer will help the employee change the behaviour.

- If appropriate, agree on a date when you will review the situation together, and ensure that the performance issue has changed for the better.

- Ensure that the employee understands the repercussions if the behaviour does not change. This must also be documented on the progressive discipline form.

- Both the employee and the employer should sign this written record of the conversation that outlines the issue, the solution, and the timeline for the change.

- Give the employee a copy of the written documentation for his or her own records.

- Follow-up on the agreed-upon date.

Step 3: Suspension without Pay

Depending on the situation there are times when it is appropriate to suspend an employee and times when it is not.

The rules on suspending employees without pay may depend on the specific situation, and, therefore, it is advised that employers review the provincial employment standards (Ontario Employment Standards, BC Employment Standards Act, or other provincial employment standards legislation) before carrying out a suspension without pay.

The rules on suspending employees without pay may depend on the specific situation, and, therefore, it is advised that employers review the provincial employment standards (Ontario Employment Standards, BC Employment Standards Act, or other provincial employment standards legislation) before carrying out a suspension without pay.Step 4: Termination

If a problem is not resolved after appropriate warning, you may have to terminate an employee. As well, there may be cases when you want to terminate an employee immediately before going through steps 1 to 3.

Employment standards legislation in most provinces establishes a three-month probationary period during which an employee can be terminated for any reason, without notice. The only exceptions to termination within the probation period are any reason deemed discriminatory under human rights legislation, such as religious beliefs or nationality.

After the probationary period, the employer must have just cause for termination or otherwise provide sufficient notice or severance. It is recommended that you consult with your provincial labour regulations to confirm what is deemed “just cause.” Poor work performance is not normally considered just cause unless the progressive discipline process has been followed and the employee has been given sufficient time to improve.

Just cause normally includes any of the following as grounds for immediate dismissal:

- Theft, fraud, or embezzlement

- Fighting

- Working while under the influence of drugs or alcohol

- Any conduct that threatens the safety of others*

- Gross insubordination

*To learn more about warning signs of violence and best practices in designing and implementing anti-violence workplace strategies see Workplace Violence: Preventing and Minimizing Tragedy.

Termination

If you are going to terminate an employee, you must have all the pertinent documentation in order and follow all the rules. If you do not, you risk legal repercussions for wrongful termination.If you have a human resources department, it is advisable to discuss the termination process with them beforehand. If your business is small and there is no formal human resources function, be sure you follow the employment standards regulations for your jurisdiction. If you feel unsure about any rule, you may want to contact a similar business that has a human resource department or the provincial Employment Standards Branch for advice. In all termination cases, aim to preserve the dignity of the employee and to have them leave with the feeling of being treated fairly and with respect. See the suggestions below for additional guidelines for best practices when terminating an employee.

Let’s Focus: Steps When Terminating an Employee

Regardless of the specific rules for your jurisdiction, you should follow these general steps when terminating an employee:

Regardless of the specific rules for your jurisdiction, you should follow these general steps when terminating an employee:

- A discussion with the employee must occur before a final determination is reached. Inform the employee about the nature of the problem.

- The employee must be given an opportunity to explain his or her action and to provide information.

- If the employee provides pertinent information, you must investigate where appropriate.

- A written notice of termination must be prepared after the discussion and consideration of all available information.

- When you meet with the employee for the final termination meeting, hold it in a private location where the employee will not have to walk past co-workers afterwards.

- Have a witness or backup present in case the conversation gets heated.

- Explain how the employee has continued to perform below expectations. Refer to warnings given earlier.

- Announce the termination.

- Collect all property of the company, such as keys and uniforms.

- Ensure that the employee’s hours of work are sent to the payroll department, and final cheques and vacation pay are paid out according to the provincial regulations.

- Inform the employee of any information they need to know, such as when the final pay cheque will be ready if not already available, where to hand in keys and uniform, and if and when there will be an exit interview.

Adapted Works

“Organizational Structure and Change” in Organizational Behaviour by Saylor Academy is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

Developing Codes of Ethics and Statements of Values by William Frey and Jose A. Cruz-Cruz is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Progressive Discipline and Termination Processes” in Human Resources in the Food Service and Hospitality Industry by The BC Cook Articulation Committee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.