1.4 Benefits and Challenges of Conflict

Benefits and Challenges of Conflict

As we discussed with the traditional view of conflict, many people often assume that all conflict is necessarily bad and should be eliminated or avoided at all costs. On the contrary, there are some circumstances in which a moderate amount of conflict can be helpful a bring energy and focus to a task. For instance, conflict can lead to the search for new ideas and new mechanisms as solutions to organizational problems. It can also facilitate employee motivation in cases where employees feel a need to excel and, as a result, push themselves in order to meet performance objectives.

Conflict can at times help individuals and group members grow, develop self-identities, and to create change and stability (Coser, 1956). Conflict can stimulate the conversations of important issues and spur change. Within a group, productive conflict can lead to consensus and group cohesiveness.

Conflict can, on the other hand, have negative consequences for both individuals and organizations when people divert energies away from performance and goal attainment and direct them toward resolving the conflict. During conflict, it can be easy for judgement to get clouded and to lose sight of end-goals. Conflict in groups can lead to lack of motivation, social loafing, and other withdrawal behaviours. Continued conflict can make for a toxic work environment and take a heavy toll on our psychological well-being. As we learn in future chapters, conflict can be a stressor in the workplace and contribute to burnout. Finally, continued conflict can also affect the social climate of the group and inhibit group cohesiveness.

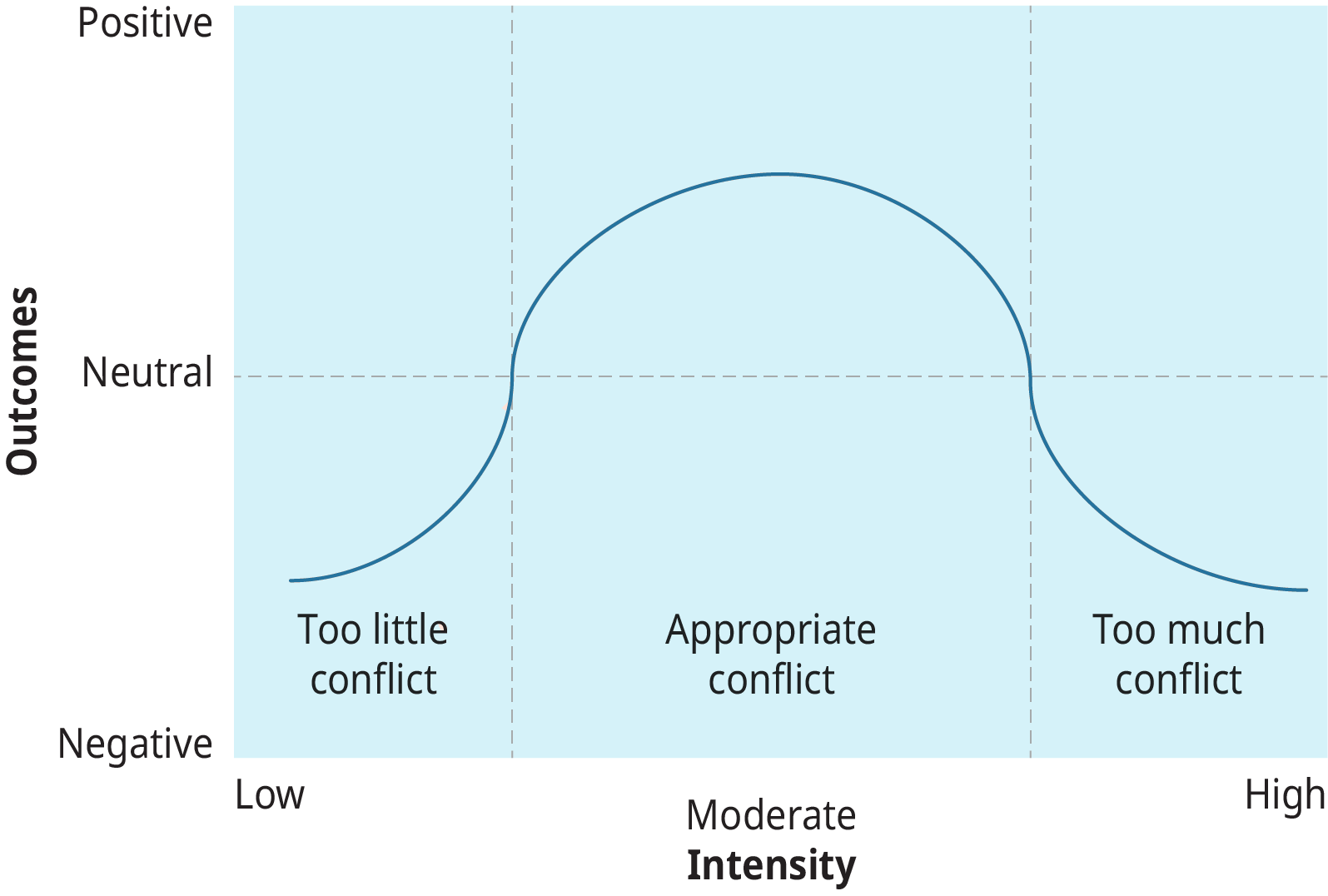

As we discussed earlier in the chapter with the interactionist view, conflict can be either functional or dysfunctional and a benefit or a detriment in work situations depending upon the nature of the conflict, its intensity, and its duration. Indeed, both too much and too little conflict can lead to a variety of negative outcomes, as discussed above. This is shown in figure 1.4 below. In such circumstances, a moderate amount of conflict may be the best course of action. The issue for management, therefore, is not how to eliminate conflict but rather how to manage and resolve it when it occurs.

Costs of Conflict in Canadian Workplaces

Conflict in organizations represents an important topic for managers. Across decades of research, it has been consistently found that managers spend 15-20% of their time dealing with some form of conflict (Thomas & Schmidt, 1978; Rahim, 1983; Half, 2017). In another study, Graves (1983) found that managerial skill in handling conflict was a major predictor of managerial success and effectiveness. Many professionals do not receive training in conflict management even though they are expected to do it as part of their job. A lack of training and a lack of competence could be a recipe for disaster. Being able to manage conflict situations can make life more productive and less stressful.

A study of Canadian workplaces conducted by Psychometrics (2015) stated that conflict was reported in virtually all workplaces and were often associated with negative outcomes such as increased levels of sickness, bullying, termination of employment and turnover. Their study reported that in the Canadian workplaces surveyed, “the most common causes of conflict are warring egos and personality clashes (86%), poor leadership (73%), lack of honesty (67%), stress (64%), and clashing values (59%)” (p. 7). The HR consultants from Morneau Shepell estimate that workplace conflict costs business in Canada at least two billion dollars each year (Consulting.ca, 2021). Conflict between coworkers and between staff and management, as well as aggressive or abusive behaviour by various parties can negatively impact a workplaces’ productivity. It can also lead to expensive legal fees and time in court if conflict moves into formal legal proceedings. Prolonged stress due to conflict and toxic workplaces can contribute to burnout and mental health disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression), which are leading causes of disability in Canada and significant contributors to loss of productivity in the Canadian workplace each year (CAMH, 2020).

Let’s Focus: Why Should I Care About Conflict?

What if you are thinking to yourself: I’m not a manager, I’m just a student. Why should I care about conflict management?

What if you are thinking to yourself: I’m not a manager, I’m just a student. Why should I care about conflict management?

Conflict is an inevitable part of work and can take a negative emotional toll. It takes effort to ignore someone or be passive aggressive, and the anger or guilt we may feel after blowing up at someone are valid negative feelings. However, conflict isn’t always negative or unproductive. In fact, numerous research studies have shown that quantity of conflict in a relationship is not as important as how the conflict is handled (Markman et al., 1993). Additionally, when conflict is well managed, it has the potential to lead to more rewarding and satisfactory relationships (Canary & Messman, 2000).

Since conflict is present in our personal and professional lives, the ability to manage conflict and negotiate desirable outcomes can help us be more successful at both. You don’t have to wait until you are a manager to need or benefit from these skills. Improving your competence in dealing with conflict can yield positive effects on your personal and professional relationships right now. Additionally, conflict management strategies can be used to learn more about yourself and others, and to deepen your relationships and connections with the people in your life. The negative effects of poorly handled conflict, which can range from an awkward last few weeks of the semester with a college roommate to anger, divorce, illness, or violence, can be minimized by improving our ability and capacity to manage the normal and naturally occurring conflict in our lives. The ideas, tools, and strategies we explore in this book will seem simple, but they won’t always be easy to implement.

In this book, you will be putting language and frameworks to the conflict experiences you have had in your life. We will be approaching the concepts and frameworks from three angles:

- Theory – Examining existing psychological theories, as they relate to conflict management in the workplace.

- Mindset – Examining our beliefs and ideas about conflict, communication, and people. Developing our awareness and understanding of how our mindset impacts our approach to conflict.

- Skillset – Examining what skills you currently have and what skills you need to improve in order to more effectively manage conflict.

By the end of this book, I hope that you have a new understanding about the nature of conflict, an open mindset towards embracing conflict, and a skillset that supports you in managing the conflicts you encounter in your life.

Adapted Works

“What Is Conflict?” by Freedom Learning Group, Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Conflict and Negotiations” in Organizational Behaviour by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

Canary, D. J., & Messman, S. J. (2000). Relationship conflict. In C. Hendrick & S. S. Hendrick (Eds.), Close relationships: A sourcebook (pp. 261-270). Sage.

CAMH. (2020, January 26). Workplace mental health – A review and recommendations. https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/workplace-mental-health/workplacementalhealth-a-review-and-recommendations-pdf.pdf

Consulting.ca (2021, April 21). Workplace conflict consultancy: The Pacificus Group launches in Toronto. https://www.consulting.ca/news/2231/workplace-conflict-consultancy-the-pacificus-group-launches-in-toronto

Coser, L. (1956). The functions of social conflict. Free Press.

Graves, J. (1978). Successful management and organizational mugging. In J. Papp (Ed.). New directions in human resources management (pp. XX). Prentice-Hall.

Markman, H. J., Renick, M. J., Floyd, F. J., Stanley, S. M., & Clements, M. (1993). Preventing marital distress through communication and conflict management training: A 4- and 5-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(1), 70–77.

Psychometrics. (2015). Warring egos, toxic individuals, feeble leadership: A study of conflict in the Canadian workplace. https://www.psychometrics.com/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/conflictstudy_09.pdf

Rahim, M. (1983). A measure of styles of handing interpersonal conflict. Academy of Management Journal, 368-376.

Half, R. (2017, March 9). Clash of the coworkers: CFOs spend nearly one day a week resolving staff conflicts. Robert Half Talent Soultions. https://rh-us.mediaroom.com/2017-03-09-Clash-Of-The-Coworkers

Thomas, K., & Schmidt, W. (1976). A survey of managerial interests with respect to conflict. Academy of Management Journal, 19, 315-318. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/255781