9.3 Group Life Cycle

Groups are dynamic systems in constant change. Groups grow together and eventually come apart. People join groups and others leave. This dynamic changes and transforms the very nature of the group. Group socialization involves how the group members interact with one another and form relationships. Just as you were once born and changed the caregivers that raised you, they changed you. You came to know a language and culture, a value system, and set of beliefs that influence you to this day. You came to be socialized, to experience the process of learning to associate, communicate, or interact within a group. A group you belong to this year—perhaps a soccer team or the cast of a play—may not be part of your life next year. And those who are in leadership positions may ascend or descend the leadership hierarchy as the needs of the group, and other circumstances, change over time.

Group Life Cycle Patterns

Your life cycle is characterized with several steps, and while it doesn’t follow a prescribed path, there are universal stages we can all recognize. You were born. You didn’t choose your birth, your parents, your language, or your culture, but you came to know them through communication. You came to know yourself, learned skills, discovered talents, and met other people. You learned, worked, lived, and loved, and as you aged, minor injuries took longer to heal. You competed in ever-increasing age groups in your favorite sport, and while your time for each performance may have increased as you aged, your experience allowed you to excel in other ways. Where you were once a novice, you have now learned something to share. You lived to see some of your friends pass before you, and the moment will arrive when you too must confront death.

In the same way, groups experience similar steps and stages and take on many of the characteristics we associate with life (Moreland & Levine, 1982). They grow, overcome illness and dysfunction, and transform across time. No group, just as no individual, lives forever.

Your first day on the job may be comparable to the first day you went to school. At home, you may have learned some of the basics, like how to write with a pencil, but knowledge of that skill and its application are two different things. In school, people spoke and acted in different ways than at home. Gradually, you came to understand the meaning of recess, the importance of raising your hand to get the teacher’s attention, and how to follow other school rules. At work, you may have had academic training for your profession, but the knowledge you learned in school only serves as your foundation—much as your socialization at home served to guide you at school. On the job they use jargon terms, have schedules that may include coffee breaks (recess), have a supervisor (teacher), and have rules, explicit and understood. On the first day, it was all new, even if many of the elements were familiar.

In order to better understand group development and its life cycle, many researchers have described the universal stages and phases of groups. While there are modern interpretations of these stages, most draw from the model proposed by Bruce Tuckman specifies the usual order of the phases of group development and allows us to predict several stages we can anticipate as we join a new group.

Forming

Tuckman (1965) begins with the forming stage as the initiation of group formation. This stage is also called the orientation stage because individual group members come to know each other. Group members who are new to each other and can’t predict each other’s behavior can be expected to experience the stress of uncertainty. Uncertainty theory states that we choose to know more about others with whom we have interactions in order to reduce or resolve the anxiety associated with the unknown (Berger & Calabrese, 1975; Berger, 1986; Gudykunst, 1995). The more we know about others and become accustomed to how they communicate, the better we can predict how they will interact with us in future contexts. If you learn that Monday mornings are never a good time for your supervisor, you quickly learn to schedule meetings later in the week. Individuals are initially tentative and display caution as they begin to learn about the group and its members.

Storming

If you don’t know someone very well, it is easy to offend. Each group member brings to the group a set of experiences, combined with education and a self-concept. You won’t be able to read this information on a nametag, but instead you will only come to know it through time and interaction. Since the possibility of overlapping and competing viewpoints and perspectives exists, the group will experience a storming stage, a time of struggles as the members themselves sort out their differences. There may be more than one way to solve the problem or task at hand, and some group members may prefer one strategy over another. Some members of the group may be more senior to the organization than you, and members may treat them differently. Some group members may be as new as you are and just as uncertain about everyone’s talents, skills, roles, and self-perceptions. The wise business communicator will anticipate the storming stage and help facilitate opportunities for the members to resolve uncertainty before the work commences. There may be challenges for leadership, and there may be conflicting viewpoints. The sociology professor sees the world differently than the physics professor. The sales agent sees things differently than someone from accounting. A manager who understands and anticipates this normal challenge in the group’s life cycle can help the group become more productive.

A clear definition of the purpose and mission of the group can help the members focus their energies. Interaction prior to the first meeting can help reduce uncertainty. Coffee and calories can help bring a group together. Providing the group with what they need and opportunities to know each other prior to their task can increase efficiency.

Although little seems to get accomplished at this stage, group members are becoming more authentic as they express their deeper thoughts and feelings. What they are really exploring is “Can I truly be me, have power, and be accepted?” During this chaotic stage, a great deal of creative energy that was previously buried is released and available for use, but it takes skill to move the group from storming to norming. In many cases, the group gets stuck in the storming phase.

Let’s Focus

Let’s Focus

The Storming Phase

Avoid Getting Stuck in the Storming Phase!

There are several steps you can take to avoid getting stuck in the storming phase of group development. Try the following if you feel the group process you are involved in is not progressing:

- Normalize conflict. Let members know this is a natural phase in the group-formation process.

- Be inclusive. Continue to make all members feel included and invite all views into the room. Mention how diverse ideas and opinions help foster creativity and innovation.

- Make sure everyone is heard. Facilitate heated discussions and help participants understand each other.

- Support all group members. This is especially important for those who feel more insecure.

- Remain positive. This is a key point to remember about the group’s ability to accomplish its goal.

- Don’t rush the group’s development. Remember that working through the storming stage can take several meetings.

Norming

Groups that make a successful transition from the storming stage will next experience the norming stage, where the group establishes norms, or informal rules, for behavior and interaction. Who speaks first? Who takes notes? Who is creative, who is visual, and who is detail-oriented? Sometimes our job titles and functions speak for themselves, but human beings are complex. We are not simply a list of job functions, and in the dynamic marketplace of today’s business environment you will often find that people have talents and skills well beyond their “official” role or task. Drawing on these strengths can make the group more effective.

The norming stage is marked by less division and more collaboration. The level of anxiety associated with interaction is generally reduced, making for a more positive work climate that promotes listening. When people feel less threatened and their needs are met, they are more likely to focus their complete attention on the purpose of the group. If they are still concerned with who does what and whether they will speak in error, the interaction framework will stay in the storming stage. Tensions are reduced when the normative expectations are known and the degree to which a manager can describe these at the outset can reduce the amount of time the group remains in uncertainty. Group members generally express more satisfaction with clear expectations and are more inclined to participate.

Performing

Ultimately, the purpose of a work group is performance, and the preceding stages lead us to the performing stage, in which the group accomplishes its mandate, fulfills its purpose, and reaches its goals. To facilitate performance, group members can’t skip the initiation of getting to know each other or the sorting out of roles and norms, but they can try to focus on performance with clear expectations from the moment the group is formed. Productivity is often how we measure success in business and industry, and the group has to produce. Outcome assessments may have been built into the system from the beginning to serve as a benchmark for success. Wise managers know how to celebrate success, as it brings more success, social cohesion, group participation, and a sense of job satisfaction. Incremental gains toward a benchmark may also be cause for celebration and support, and failure to reach a goal should be regarded as an opportunity for clarification.

It is generally wiser to focus on the performance of the group rather than individual contributions. Managers and group members will want to offer assistance to underperformers as well as congratulate members for their contributions. If the goal is to create a community where competition pushes each member to perform, individual highlights may serve your needs, but if you want a group to solve a problem or address a challenge as a group, you have to promote group cohesion. Members need to feel a sense of belonging, and praise (or the lack thereof) can be a sword with two edges: one stimulates and motivates while the other demoralizes and divides.

Groups should be designed to produce and perform in ways and at levels that individuals cannot, or else you should consider compartmentalizing the tasks. The performing stage is where the productivity occurs, and it is necessary to make sure the group has what it needs to perform. Missing pieces, parts, or information can stall the group and reset the cycle to storming all over again. Loss of performance is inefficiency, which carries a cost. Managers will be measured by the group’s productivity and performance. Make sure the performing stage is one that is productive and healthy for its members.

Adjourning

Now, as typically happens, all groups will eventually have to move on to new assignments. In the adjourning stage, members leave the group. The group may cease to exist or it may be transformed with new members and a new set of goals. Others will be reassigned to tasks that require their talents and skills, and you may or may not collaborate with them in the future.

You may miss the interactions with the members, even the more cantankerous ones, and will experience both relief and a sense of loss. Like life, the group process is normal, and mixed emotions are to be expected. A wise manager anticipates this stage and facilitates the separation with skill and ease. We often close this process with a ritual marking its passing, though the ritual may be as formal as an award or as informal as a “thank you” or a verbal acknowledgement of a job well done over coffee and calories. It is important not to forget that groups can reach the adjourning stage without having achieved success. Some businesses go bankrupt, some departments are closed, and some individuals lose their positions after a group fails to perform. Adjournment can come suddenly and unexpectedly or gradually and piece by piece. Either way, a skilled business communicator will be prepared and recognize it as part of the classic group life cycle.

High Performing Groups and The Punctuated-Equilibrium Model

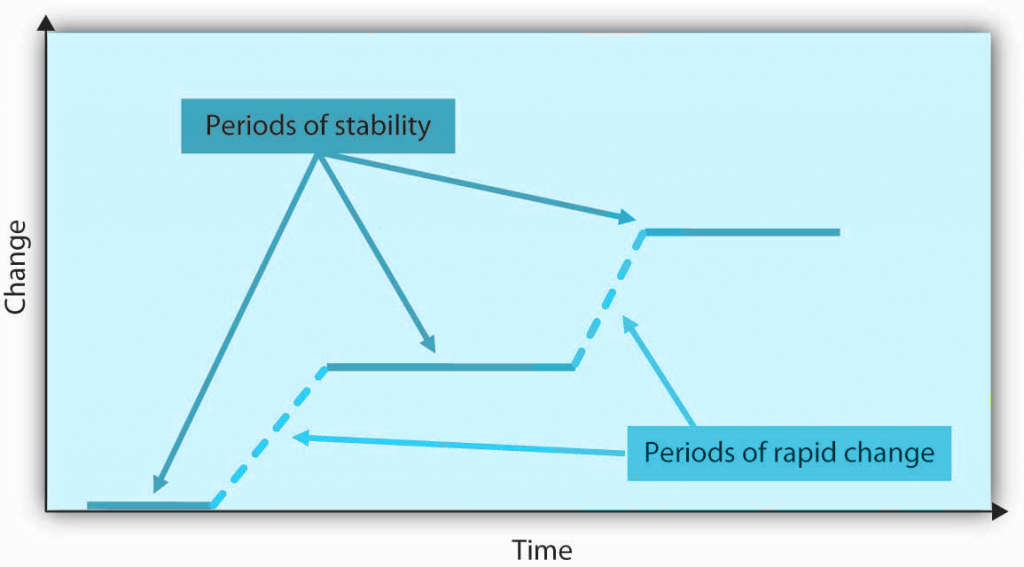

As you may have noted, the five-stage model we have just reviewed is a linear process. According to the model, a group progresses to the performing stage, at which point it finds itself in an ongoing, smooth-sailing situation until the group dissolves. In reality, subsequent researchers, most notably Joy H. Karriker, have found that the life of a group is much more dynamic and cyclical in nature (Karriker, 2005). For example, a group may operate in the performing stage for several months. Then, because of a disruption, such as a competing emerging technology that changes the rules of the game or the introduction of a new CEO, the group may move back into the storming phase before returning to performing. Think of your own experiences with project teams and the backslide that the group may have taken when another team member was introduced or when a leader or project sponsor changed a new project task. The team has to re-group and will likely re-storm and re-form before getting back to performing as a team. Ideally, any regression in the linear group progression will ultimately result in a higher level of functioning.

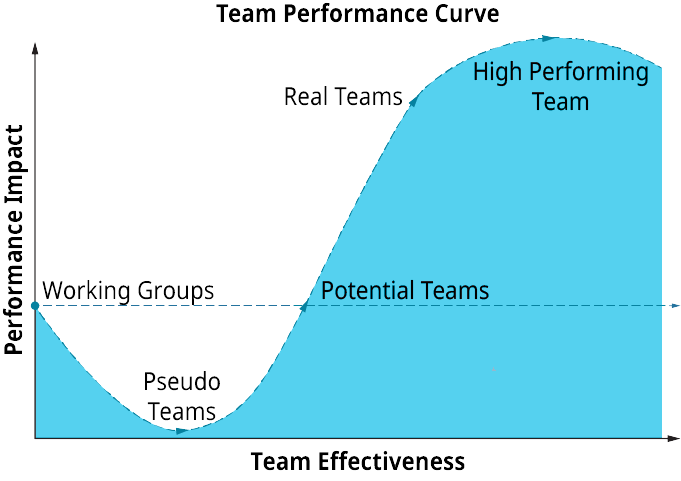

Katzenberg and Smith (2005), in their study of teams, have created a “team performance curve” that graphs the journey of a team from a working group to a high-performing team. The team performance curve is illustrated in Figure 9.3

Life Cycle of Member Roles

Just as groups go through a life cycle when they form and eventually adjourn, so do the group members fulfill different roles during this life cycle. These roles, proposed by Richard Moreland and John Levine are summarized in Table 9.4.

Table 9.4 Life Cycle of Member Roles

| 1. Potential member | Curiosity and interest |

|---|---|

| 2. New member | Joined the group but still an outsider, and unknown |

| 3. Full member | Knows the rules and is looked to for leadership |

| 4. Divergent member | Focuses on differences |

| 5. Marginal member | No longer involved |

| 6. Ex-Member | No longer considered a member |

| Source: Human Relations | |

Consider This

Consider This

Group Scenario

Suppose you are about to graduate from school and you are in the midst of an employment search. You’ve gathered extensive information on a couple of local businesses and are aware that they will be participating in the university job fair. You’ve explored their websites, talked to people currently employed at each company, and learned what you can from the public information available. At this stage, you are considered a potential member. You may have an electrical, chemical, or mechanical engineering degree soon, but you are not a member of an engineering team.

You show up at the job fair in professional attire and completely prepared. The representatives of each company are respectful, cordial, and give you contact information. One of them even calls a member of the organization on the spot and arranges an interview for you next week. You are excited at the prospect and want to learn more. You are still a potential member.

The interview goes well the following week. The day after the meeting, you receive a call for a follow-up interview that leads to a committee interview. A few weeks later, the company calls you with a job offer. However, in the meantime, you have also been interviewing with other potential employers, and you are waiting to hear back from two of them. You are still a potential member

As a member of a new group, you may learn new customs, traditions, and group norms. After careful consideration, you decide to take the job offer and start the next week. The projects look interesting, you’ll be gaining valuable experience, and the commute to work is reasonable. Your first day on the job is positive, and they’ve assigned you a mentor. The conversations are positive, but you feel lost at times, as if they are speaking a language you can’t quite grasp. As a new group member, your level of acceptance will increase as you begin learning the groups’ rules, spoken and unspoken (Fisher, 1970). You will gradually move from the potential member role to the role of new group member as you learn to fit into the group.

Over time and projects, you gradually increase your responsibilities. You are no longer looked at as the new person, and you can follow almost every conversation. You can’t quite say, “I remember when,” because your tenure hasn’t been that long, but you are a known quantity and know your way around. You are a full member of the group. Full members enjoy knowing the rules and customs and can even create new rules. New group members look to full members for leadership and guidance. Full group members can control the agenda and have considerable influence on the agenda and activities.

Full members of a group, however, can and do come into conflict. When you were a new member, you may have remained silent when you felt you had something to say, but now you state your case. There is more than one way to get the job done. You may suggest new ways that emphasize efficiency over existing methods. Coworkers who have been working in the department for several years may be unwilling to adapt and change, resulting in tension. Expressing different views can cause conflict and may even interfere with communication.

When this type of tension arises, divergent group members pull back, contribute less, and start to see themselves as separate from the group. Divergent group members have less eye contact, seek out each other’s opinion less frequently, and listen defensively. In the beginning of the process, you felt a sense of belonging, but now you don’t. Marginal group members start to look outside the group for their interpersonal needs.

After several months of trying to cope with these adjustments, you decide that you never really investigated the other two companies, that your job search process was incomplete. Perhaps you should take a second look at the options. You will report to work on Monday but will start the process of becoming an ex-member, one who no longer belongs. You may experience a sense of relief upon making this decision, given that you haven’t felt like you belonged to the group for a while. When you line up your next job and submit your resignation, you make it official.

This process has no set timetable. Some people overcome differences and stay in the group for years; others get promoted and leave the group only when they get transferred to regional headquarters. As a skilled business communicator, you will recognize the signs of divergence, just as you have anticipated the storming stage and do your best to facilitate success.

Let’s Review

Let’s Review

- Groups and their individual members come together and grow apart in predictable patterns.

- Group lifecycle patterns refer to the process or stages of group development.

- There are five stages to the group development process, which include forming, norming, storming, performing, and adjourning.

- Within each of the stages, group members have a variety of roles, which include potential member, new member, full member, divergent member, marginal member, and an ex-member.

Exercises

Exercises

- Is it possible for an outsider (a nongroup member) to help a group move from the storming stage to the norming stage? Explain your answer and present it to the class.

- Think of a group of which you are a member and identify some roles played by group members, including yourself. Have your roles, and those of others, changed over time? Are some roles more positive than others? Discuss your answers with your classmates.

- In the course where you are using this book, think of yourself and your classmates as a group. At what stage of group formation are you currently? What stage will you be at when the school year ends?

- Think of a group you no longer belong to. At what point did you become an ex-member? Were you ever a marginal group member or a full member? Write a two- to three-paragraph description of the group, how and why you became a member, and how and why you left.

References

This section is adapted from:

7.2 Group Life Cycles and Member Roles in Human Relations by Saylor Academy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

9.2 Group Dynamics in NCC Organizational Behaviour which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Berger, C. (1986). Response uncertain outcome values in predicted relationships: Uncertainty reduction theory then and now. Human Communication Research, 13, 34–38.

Berger, C., & Calabrese, R. (1975). Some explorations in initial interactions and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research, 1, 99–112.

Fisher, B. A. (1970). Decision emergence: Phases in group decision making. Speech Monographs, 37, 56–66.

Gersick, C. J. G. (1991). Revolutionary change theories: A multilevel exploration of the punctuated equilibrium paradigm. Academy of Management Review, 16, 10–36.

Gudykunst, W. (1995). Anxiety/uncertainty management theory. In R. W. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 8–58). Sage.

Karriker, J. H. (2005). Cyclical group development and interaction-based leadership emergence in autonomous teams: An integrated model. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 11, 54–64.

Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (2005). The wisdom of teams: Creating the high-performance organization. Harvard Business Review Press.

Moreland, R., & Levine, J. (1982). Socialization in small groups: Temporal changes in individual group relations. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Volume 15, pp. 137-192). Academic Press.

Tuckman, B. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384–99.