9.2 Characteristics of Effective Groups

Social Loafing

Before we discuss characteristics of effective groups, we are going to discuss a well-known effect of group work called social loafing.

Social loafing refers to the tendency of individuals to put in less effort when working in a group context. This phenomenon, also known as the Ringelmann effect, was first noted by French agricultural engineer Max Ringelmann in 1913. In one study, he had people pull on a rope individually and in groups. He found that as the number of people pulling increased, the group’s total pulling force was less than the individual efforts had been when measured alone (Karau & Williams, 1993).

Why do people work less hard when they are working with other people? Observations show that as the size of the group grows, this effect becomes larger as well (Karau & Williams, 1993). The social loafing tendency is less a matter of being lazy and more a matter of perceiving that one will receive neither one’s fair share of rewards if the group is successful nor blame if the group fails. Rationales for this behaviour include, “My own effort will have little effect on the outcome,” “Others aren’t pulling their weight, so why should I?” or “I don’t have much to contribute, but no one will notice anyway.” This is a consistent effect across a great number of group tasks and countries (Gabrenya et al., 1983; Harkins & Petty, 1982; Taylor & Faust, 1952; Ziller, 1957). Research also shows that perceptions of fairness are related to less social loafing (Price et al., 2006). Therefore, teams that are deemed as more fair should also see less social loafing.

Let’s Focus

Let’s Focus

Social Loafing in Groups

Tips for Preventing Social Loafing in Your Group

When designing a group project, here are some considerations to keep in mind:

- Carefully choose the number of individuals you need to get the task done. The likelihood of social loafing increases as group size increases (especially if the group consists of 10 or more people), because it is easier for people to feel unneeded or inadequate, and it is easier for them to “hide” in a larger group.

- Clearly define each member’s tasks in front of the entire group. If you assign a task to the entire group, social loafing is more likely. For example, instead of stating, “By Monday, let’s find several articles on the topic of stress,” you can set the goal of “By Monday, each of us will be responsible for finding five articles on the topic of stress.” When individuals have specific goals, they become more accountable for their performance.

- Design and communicate to the entire group a system for evaluating each person’s contribution. You may have a midterm feedback session in which each member gives feedback to every other member. This would increase the sense of accountability individuals have. You may even want to discuss the principle of social loafing in order to discourage it.

- Build a cohesive group. When group members develop strong relational bonds, they are more committed to each other and the success of the group, and they are therefore more likely to pull their own weight.

- Assign tasks that are highly engaging and inherently rewarding. Design challenging, unique, and varied activities that will have a significant impact on the individuals themselves, the organization, or the external environment. For example, one group member may be responsible for crafting a new incentive-pay system through which employees can direct some of their bonus to their favourite nonprofits.

- Make sure individuals feel that they are needed. If the group ignores a member’s contributions because these contributions do not meet the group’s performance standards, members will feel discouraged and are unlikely to contribute in the future. Make sure that everyone feels included and needed by the group.

In this Section:

Now that we’ve learned about the phenomenon of social loafing, let’s turn our attention towards effective teams. We will discuss characteristics of effective groups and teams based on a number of factors, including:

Team Norms

Norms are shared expectations about how things operate within a group or team. Just as new employees learn to understand and share the assumptions, norms, and values that are part of an organization’s culture, they also must learn the norms of their immediate team. This understanding helps teams be more cohesive and perform better. Norms are a powerful way of ensuring coordination within a team. For example, is it acceptable to be late to meetings? How prepared are you supposed to be at the meetings? Is it acceptable to criticize someone else’s work? These norms are shaped early during the life of a team and affect whether the team is productive, cohesive, and successful.

Let’s Focus

Let’s Focus

Establishing Norms Using Team Contracts

Scientific research, as well as experience working with thousands of teams, shows that teams that are able to articulate and agree on established ground rules, goals, and roles and develop a team contract around these standards are better equipped to face challenges that may arise within the team (Katzenback & Smith, 1993; Porter & Lilly, 1996). Having a team contract does not necessarily mean that the team will be successful, but it can serve as a road map when the team veers off course.

The following questions can help to create a meaningful team contract:

Team Values and Goals

- What are our shared team values?

- What is our team’s goal?

Team Roles and Leadership

- Who does what within this team? (Who takes notes at the meeting? Who sets

the agenda? Who assigns tasks? Who runs the meetings?) - Does the team have a formal leader? If so, what are the leaders’ roles?

Team Decision Making

- How are minor decisions made?

- How are major decisions made?

Team Communication

- Who do you contact if you cannot make a meeting?

- Who communicates with whom?

- How often will the team meet?

Team Performance

- What constitutes good team performance?

- What if a team member tries hard but does not seem to be producing quality work

- How will poor attendance/work quality be dealt with?

Group Roles

In order to accomplish its goals and maintain its norms, a group must differentiate the work activities of its members. One or more members assume leadership positions, others carry out the major work of the group, and still others serve in support roles. This specialization of activities is commonly referred to as role differentiation. More specifically, a work role is an expected behaviour pattern assigned or attributed to a particular position in the organization. It defines individual responsibilities on behalf of the group.

As we might expect, individual group members often perform several of these roles simultaneously. A group leader, for example, must focus group attention on task performance while at the same time preserving group harmony and cohesiveness. To see how this works, consider your own experience. You may be able to recognize the roles you have played in groups you have been a member of. In your experience, have you played multiple roles or single roles?

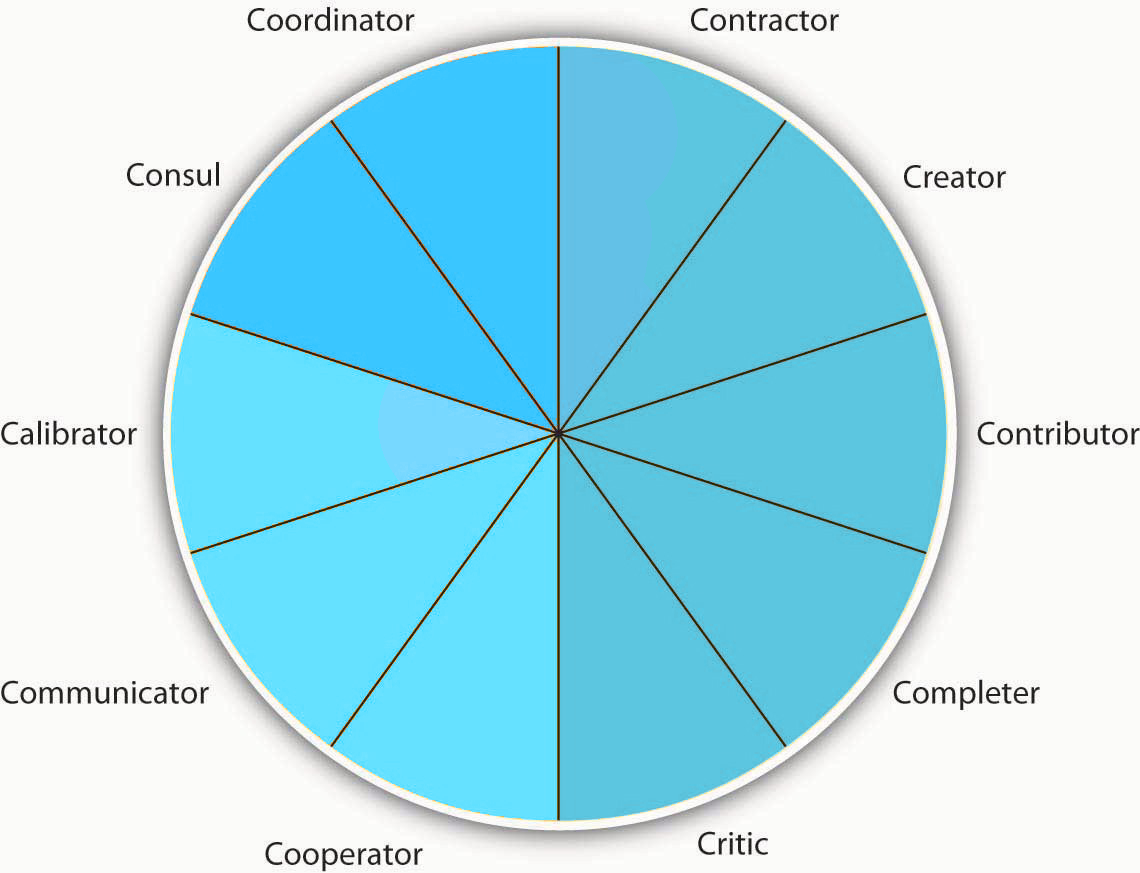

Studies show that individuals who are more aware of team roles and the behaviour required for each role perform better than individuals who do not. This fact remains true for both student project teams as well as work teams, even after accounting for personality and intelligence (Mumford et al., 2008). Early research found that the teams tend to have two categories of roles, consisting of those related to the tasks at hand and those related to the team’s functioning. For example, teams that focus only on production at all costs may be successful in the short run, but if they pay no attention to how team members feel about working 70 hours a week, they are likely to experience high turnover. Figure 9.1 lists the various roles in a team role typology chart.

Based on decades of research on teams, 10 key roles have been identified (Bales, 1950; Benne & Sheats, 1948; Belbin, 1993). Team leadership is effective when leaders are able to adapt the roles they are contributing or asking others to contribute to fit what the team needs, given its stage and the tasks at hand (Kozlowski et al., 1996; Kozlowski et al., 1996). Ineffective leaders might always engage in the same task role behaviours, when what they really need is to focus on social roles, put disagreements aside, and get back to work. While these behaviours can be effective from time to time, if the team doesn’t modify its role behaviours as things change, they most likely will not be effective.

Cohesion

Cohesion can be thought of as a kind of social glue. It refers to the degree of camaraderie within the group. Cohesive groups are those in which members are attached to each other and act as one unit. Generally speaking, the more cohesive a group is, the more productive it will be and the more rewarding the experience will be for the group’s members (Beal et al., 2003; Evans & Dion, 1991). Members of cohesive groups tend to have the following characteristics: They have a collective identity; they experience a moral bond and a desire to remain part of the group; they share a sense of purpose, working together on a meaningful task or cause; and they establish a structured pattern of communication.

The fundamental factors affecting group cohesion include the following:

The fundamental factors affecting group cohesion include the following:

- Similarity. The more similar group members are in terms of age, sex, education, skills, attitudes, values, and beliefs, the more likely the group will bond.

- Stability. The longer a group stays together, the more cohesive it becomes.

- Size. Smaller groups tend to have higher levels of cohesion.

- Support. When group members receive coaching and are encouraged to support their fellow team members, group identity strengthens.

- Satisfaction. Cohesion is correlated with how pleased group members are with each other’s performance, behaviour, and conformity to group norms.

As you might imagine, there are many benefits in creating a cohesive group. Members are generally more personally satisfied and feel greater self-confidence and self-esteem when in a group where they feel they belong. For many, membership in such a group can be a buffer against stress, which can improve mental and physical well-being. Because members are invested in the group and its work, they are more likely to regularly attend and actively participate in the group, taking more responsibility for the group’s functioning. In addition, members can draw on the strength of the group to persevere through challenging situations that might otherwise be too hard to tackle alone.

Let’s Focus

Let’s Focus

Cohesive Team Building

Steps to Creating and Maintaining a Cohesive Team

- Align the group with the greater organization. Establish common objectives in which members can get involved.

- Let members have choices in setting their own goals. Include them in decision-making at the organizational level.

- Define clear roles. Demonstrate how each person’s contribution furthers the group goal—everyone is responsible for a special piece of the puzzle.

- Situate group members in close proximity to each other. This builds familiarity.

- Give frequent praise. Both individuals and groups benefit from praise. Also, encourage them to praise each other. This builds individual self-confidence, reaffirms positive behaviour, and creates an overall positive atmosphere.

- Treat all members with dignity and respect. This demonstrates that there are no favourites and everyone is valued.

- Celebrate differences. This highlights each individual’s contribution while also making diversity a norm.

- Establish common rituals. Thursday morning coffee, monthly potlucks—these reaffirm group identity and create shared experiences.

Can a Group Have Too Much Cohesion?

Keep in mind that groups can have too much cohesion. Because members can come to value belonging over all else, an internal pressure to conform may arise, causing some members to modify their behaviour to adhere to group norms. Members may become conflict-avoidant, focusing more on trying to please each other so as not to be ostracized. In some cases, members might censor themselves to maintain the party line. As such, there is a superficial sense of harmony and less diversity of thought. Having less tolerance for deviants, who threaten the group’s static identity, cohesive groups will often excommunicate members who dare to disagree.

Members attempting to make a change may even be criticized or undermined by other members, who perceive this as a threat to the status quo. The painful possibility of being marginalized can keep many members in line with the majority.The more strongly members identify with the group, the easier it is to see outsiders as inferior, or enemies in extreme cases, which can lead to increased insularity. This form of prejudice can have a downward spiral effect. Not only is the group not getting corrective feedback from within its own confines, it is also closing itself off from input and a cross-fertilization of ideas from the outside. In such an environment, groups can easily adopt extreme ideas that will not be challenged. Denial increases as problems are ignored and failures are blamed on external factors. With limited, often biased, information and no internal or external opposition, groups like these can make disastrous decisions. Groupthink is a group pressure phenomenon that increases the risk of the group making flawed decisions by allowing reductions in mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment. Groupthink is most common in highly cohesive groups (Janis, 1972). You’ll read more about groupthink later in this chapter.

Cohesive groups can go awry in much milder ways. For example, group members can value their social interactions so much that they have fun together but spend little time on accomplishing their assigned task. Or a group’s goal may begin to diverge from the larger organization’s goal, and those trying to uphold the organization’s goal may be ostracized (e.g., teasing the class “brain” for doing well in school).

In addition, research shows that cohesion leads to acceptance of group norms (Goodman et al., 1987). Groups with high task commitment do well, but imagine a group where the norms are to work as little as possible? As you might imagine, these groups get little accomplished and can actually work together against the organization’s goals.

Collective Efficacy

Collective efficacy refers to a group’s perception of its ability to perform successfully (Bandura, 1997). Collective efficacy is influenced by a number of factors, including watching others (“that group did it and we’re better than them”), verbal persuasion (“we can do this”), and how a person feels (“this is a good group”). Research shows that a group’s collective efficacy is related to its performance (Gully et al., 2002; Porter, 2005; Tasa et al., 2007). In addition, this relationship is higher when task interdependence (the degree an individual’s task is linked to someone else’s work) is high rather than low.

Emotional Intelligence

Without a doubt, most, if not all of us, will work in groups in our workplace. Even if we seem to have a somewhat isolated job, part of what we do will impact others. Developing skills that can help us work better in these groups relates to the social awareness and relationship management aspects of emotional intelligence. These two skills—the ability to understand social cues that can affect others and our ability to communicate and maintain good relationships—are the cornerstones in any group situation.

For example, in the group development process, we depend greatly on our social awareness skills in order to make successful first impressions during the forming stage. We use our ability to resolve conflict during the storming and norming phase. Having the skills to handle these different phases is key to successful and productive group work. Have you ever worked with a dysfunctional group, perhaps on a class project? These types of groups are lacking in communication and possibly emotional intelligence skills, which can make the group more cohesive. Group cohesiveness is the goal in any type of group setting. This makes the performing stage more productive, less stressful, and maybe even enjoyable!

In a study by Jordan and Troth (2004), there was a significant correlation between higher team performance and the emotional intelligence skills of the team members. Being able to understand your own emotions (self-awareness), manage them (self-management), and establish positive relationships built on trust is what makes groups work most effectively.

Self-assessments

Self-assessments

Exercises

Exercises

- Think about the most cohesive group you have ever been in. How did it compare in terms of similarity, stability, size, support, and satisfaction?

- Why do you think social loafing occurs within groups?

- Have you seen instances of collective efficacy helping or hurting a team? Please explain your answer.

- What can be done to combat social loafing?

References

This section is adapted from:

Chapter 7: Working Effectively in Groups in Human Relations by Saylor Academy, which is under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

Chapter 9: Managing Groups and Teams in Organizational Behaviour for Seneca College, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

9.2 Work Group Structure in Organizational Behaviour by Rice University, OpenStax which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Bales, R. F. (1950). Interaction process analysis: A method for the study of small groups. Addison-Wesley.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Jossey-Bass.

Beal, D. J., Cohen, R. R., Burke, M. J., & McLendon, C. L. (2003). Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 989–1004.

Belbin, R. M. (1993). Management teams: Why they succeed or fail. Butterworth Heinemann.

Benne, K. D., & Sheats, P. (1948). Functional roles of group members. Journal of Social Issues, 4, 41–49.

Evans, C. R., & Dion, K. L. (1991). Group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis. Small Group Research, 22, 175–186.

Gabrenya, W. L., Latane, B., & Wang, Y. (1983). Social loafing in cross-cultural perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Perspective, 14, 368–384.

Goodman, P. S., Ravlin, E., & Schminke, M. (1987). Understanding groups in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 9, 121–173.

Gully, S. M., Incalcaterra, K. A., Joshi, A., & Beaubien, J. M. (2002). A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: Interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 819–832.

Harkins, S., & Petty, R. E. (1982). Effects of task difficulty and task uniqueness on social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 1214–1229.

Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink. Houghton Mifflin.

(2004). Managing emotions during team problem solving: Emotional Intelligence and conflict resolution, Human Performance, 17(2), 195-218, doi: 10.1207/s15327043hup1702_4

Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 681–706.

Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (1993). The rules for managing cross‐functional reengineering teams. Planning Review, 21(2), 12-13.

Kozlowski, S. W. J., Gully, S. M., McHugh, P. P., Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (1996). A dynamic theory of leadership and team effectiveness: Developmental and task contingent roles. In G. Ferris (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resource management (pp. 253–305). JAI Press.

Kozlowski, S. W. J., Gully, S. M., Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (1996). Team leadership and development: Theory, principles, and guidelines for training leaders and teams. In M. M. Beyerlein, D. Advances in interdisciplinary studies of work teams: Team leadership (Vol. 3, pp. 253–291). Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

Mumford, T. V., Campion, M. A., & Morgeson, F. P. (2006). Situational judgments in work teams: A team role typology. In J. A. Weekley and R. E. Ployhart (Eds.), Situational judgment tests: Theory, measurement, and application (pp. 319–344). Erlbaum.

Mumford, T. V., Van Iddekinge, C. H., Morgeson, F. P., & Campion, M. A. (2008). The team role test: Development and validation of a team role knowledge situational judgment test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 250–267.

Porter, C. O. L. H. (2005). Goal orientation: Effects on backing up behaviour, performance, efficacy, and commitment in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 811–818.

Porter, T. W., & Lilly, B. S. (1996). The effects of conflict, trust, and task commitment on project team performance. International Journal of Conflict Management, 7, 361–376.

Price, K. H., Harrison, D. A., & Gavin, J. H. (2006). Withholding inputs in team contexts: Member composition, interaction processes, evaluation structure, and social loafing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1375–1384.

Tasa, K., Taggar, S., & Seijts, G. H. (2007). The development of collective efficacy in teams: A multilevel and longitudinal perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 17–27.

Taylor, D. W., & Faust, W. L. (1952). Twenty questions: Efficiency of problem-solving as a function of the size of the group. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 44, 360–363.

Ziller, R. C. (1957). Four techniques of group decision-making under uncertainty. Journal of Applied Psychology, 41, 384–388.