8.1 Personality

Our personality differentiates us from other people, and understanding someone’s personality gives us clues about how that person is likely to act and feel in a variety of situations. In order to effectively manage organizational behaviour, an understanding of different employees’ personalities is helpful. Having this knowledge is also useful for placing people in jobs and organizations.

Our personality has a lot to do with how we relate to one another at work. How we think, what we feel, and our normal behavior characterize what our colleagues come to expect of us both in behavior and the expectation of their interactions with us. For example, let’s suppose at work you are known for being on time but suddenly start showing up late daily. This directly conflicts with your personality—that is, the fact that you are conscientious. As a result, coworkers might start to believe something is wrong. On the other hand, if you did not have this characteristic, it might not be as surprising or noteworthy. Likewise, if your normally even-tempered supervisor yells at you for something minor, you may believe there is something more to his or her anger since this isn’t a normal personality trait and also may have a more difficult time handling the situation since you didn’t expect it. When we come to expect someone to act a certain way, we learn to interact with them based on their personality. This goes both ways, and people learn to interact with us based on our personality. When we behave different than our normal personality traits, people may take time to adjust to the situation.

Personality also affects our ability to interact with others, which can impact our career success. For example, Sutin & Costa (2009) found that the personality characteristic of neuroticism (a tendency to experience negative emotional states) had more effect than any personality characteristic on determining future career success. In other words, those with positive and hopeful personalities tend to be rewarded through career success later in life.

While we will discuss the effects of personality for employee behaviour, keep in mind that the relationships we describe are modest correlations and other factors also impact workplace behaviour. For example, having a sociable and outgoing personality may encourage people to seek friends and prefer social situations. This does not mean that their personality will immediately affect their work behaviour. At work, we have a job to do and a role to perform. Therefore, our behaviour may be more strongly affected by what is expected of us, as opposed to how we want to behave. When people have a lot of freedom at work, their personality will become a stronger influence over their behaviour (Barrick & Mount, 1993).

Is it Nature or Nurture?

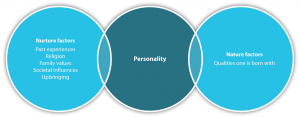

How much of our personality is in-born and biological, and how much is influenced by the environment and culture we are raised in? Psychologists who favor the biological approach believe that inherited predispositions as well as physiological processes can be used to explain differences in our personalities (Burger, 2008).

Evolutionary psychology relative to personality development looks at personality traits that are universal, as well as differences across individuals. In this view, adaptive differences have evolved and then provide a survival and reproductive advantage. Individual differences are important from an evolutionary viewpoint for several reasons. Certain individual differences, and the heritability of these characteristics, have been well documented. David Buss has identified several theories to explore this relationship between personality traits and evolution, such as life-history theory, which looks at how people expend their time and energy (such as on bodily growth and maintenance, reproduction, or parenting). Another example is costly signaling theory, which examines the honesty and deception in the signals people send one another about their quality as a mate or friend (Buss, 2009).

In the field of behavioral genetics, the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart—a well-known study of the genetic basis for personality—conducted research with twins from 1979 to 1999. In studying 350 pairs of twins, including pairs of identical and fraternal twins reared together and apart, researchers found that identical twins, whether raised together or apart, have very similar personalities (Bouchard, 1994; Bouchard et al., 1990; Segal, 2012). These findings suggest the heritability of some personality traits. Heritability refers to the proportion of difference among people that is attributed to genetics. Some of the traits that the study reported as having more than a 0.50 heritability ratio include leadership, obedience to authority, a sense of well-being, alienation, resistance to stress, and fearfulness. The implication is that some aspects of our personalities are largely controlled by genetics; however, it’s important to point out that traits are not determined by a single gene, but by a combination of many genes, as well as by epigenetic factors that control whether the genes are expressed.

Most contemporary psychologists believe temperament has a biological basis due to its appearance very early in our lives (Rothbart, 2011). As you learned when you studied lifespan development, Thomas and Chess (1977) found that babies could be categorized into one of three temperaments: easy, difficult, or slow to warm up. However, environmental factors (family interactions, for example) and maturation can affect the ways in which children’s personalities are expressed (Carter et al., 2008).

Research suggests that there are two dimensions of our temperament that are important parts of our adult personality—reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart et al., 2000). Reactivity refers to how we respond to new or challenging environmental stimuli; self-regulation refers to our ability to control that response (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981; Rothbart et al., 2011). For example, one person may immediately respond to new stimuli with a high level of anxiety, while another barely notices it.

Although there is debate between whether or not our personalities are inherent when we are born (nature) versus the way we grew up (nurture), most researchers agree that personality is usually a result of both nature and our environmental/education experiences. For example, you have probably heard someone say, “She acts just like her mother.” She likely behaves that way because she was born with some of her mother’s traits, as well as because she learned some of the behaviors her mother passed to her while growing up.

Can Our Personality Change?

If personality is stable, does this mean that it does not change? You probably remember how you have changed and evolved as a result of your own life experiences, attention you received in early childhood, the style of parenting you were exposed to, successes and failures you had in high school, and other life events. In fact, our personality changes over long periods of time. For example, we tend to become more socially dominant, more conscientious (organized and dependable), and more emotionally stable between the ages of 20 and 40, whereas openness to new experiences may begin to decline during this same time (Roberts et al., 2006). In other words, even though we treat personality as relatively stable, changes occur. Moreover, even in childhood, our personality shapes who we are and has lasting consequences for us. For example, studies show that part of our career success and job satisfaction later in life can be explained by our childhood personality (Judge & Higgins, 1999; Staw et al., 1986). This change in personality over time can be adaptive and essential to our personal growth and development, both personally and professionally.

Values

Values refer to stable life goals that people have, reflecting what is most important to them. Values are established throughout one’s life as a result of the accumulating life experiences and tend to be relatively stable (Lusk & Oliver, 1974; Rokeach, 1973). The values that are important to people tend to affect the types of decisions they make, how they perceive their environment, and their actual behaviours (Judge & Bretz, 1992; Ravlin & Meglino, 1987). Moreover, people are more likely to accept job offers when the company possesses the values people care about.Value attainment is one reason why people stay in a company, and when an organization does not help them attain their values, they are more likely to decide to leave if they are dissatisfied with the job itself (George & Jones, 1996).

What are the values people care about? There are many typologies of values. One of the most established surveys to assess individual values is the Rokeach Value Survey (Rokeach, 1974). This survey lists 18 terminal and 18 instrumental values in alphabetical order. Terminal values refer to end states people desire in life, such as leading a prosperous life and a world at peace. Instrumental values deal with views on acceptable modes of conduct, such as being honest and ethical, and being ambitious.

According to Rokeach, values are arranged in hierarchical fashion. In other words, an accurate way of assessing someone’s values is to ask them to rank the 36 values in order of importance. By comparing these values, people develop a sense of which value can be sacrificed to achieve the other, and the individual priority of each value emerges.

Table 8.1 Sample Items From Rokeach (1973) Value Survey

| Terminal Values | Instrumental Values |

|---|---|

| A world of beauty | Broad minded |

| An exciting life | Clean |

| Family security | Forgiving |

| Inner harmony | Imaginative |

| Self respect | Obedient |

| Source: Source | |

Where do values come from? Research indicates that they are shaped early in life and show stability over the course of a lifetime. Early family experiences are important influences over the dominant values. People who were raised in families with low socioeconomic status and those who experienced restrictive parenting often display conformity values when they are adults, while those who were raised by parents who were cold toward their children would likely value and desire security (Kasser et al., 2002)

Values of a generation also change and evolve in response to the historical context that the generation grows up in. Research comparing the values of different generations resulted in interesting findings. For example, Generation Xers (those born between the mid-1960s and 1980s) are more individualistic and are interested in working toward organizational goals so long as they coincide with their personal goals. This group, compared to the baby boomers (born between the 1940s and 1960s), is also less likely to see work as central to their life and more likely to desire a quick promotion (Smola & Sutton, 2002).

The values a person holds will affect his or her employment. For example, someone who has an orientation toward strong stimulation may pursue extreme sports and select an occupation that involves fast action and high risk, such as fire fighter, police officer, or emergency medical doctor. Someone who has a drive for achievement may more readily act as an entrepreneur. Moreover, whether individuals will be satisfied at a given job may depend on whether the job provides a way to satisfy their dominant values. Therefore, understanding employees at work requires understanding the value orientations of employees.

Our values also help determine our personality. Our values are those things we find most important to us. For example, if your value is calmness and peace, your personality would show this in many possible ways. You might prefer to have a few close friends and avoid going to a nightclub on Saturday nights. You might choose a less stressful career path, and you might find it challenging to work in a place where frequent conflict occurs.

We often find ourselves in situations where our values do not coincide with our coworkers or organization that employs us. For example, if Alison’s main value is connection, this may come out in a warm communication style with coworkers and an interest in their personal lives. Imagine Alison works with Tyler, whose core value is efficiency. Because of Tyler’s focus, he may find it a waste of time to make small talk with colleagues. When Alison approaches Tyler and asks about his weekend, she may feel offended or upset when he brushes her off to ask about the project they are working on together. She feels like a connection wasn’t made, and he feels like she isn’t efficient. Understanding our own values as well as the values of others can greatly help us become better communicators.

Exercise 1

Exercise 1

What Are Your Values?

What are your top five values? How do you think these values affect your personality?

| Accomplishment, success | Ease of use | Meaning | Results-oriented |

| Accountability | Efficiency | Justice | Rule of law |

| Accuracy | Enjoyment | Kindness | Safety |

| Adventure | Equality | Knowledge | Satisfying others |

| All for one & one for all | Excellence | Leadership | Security |

| Beauty | Fairness | Love, romance | Self-givingness |

| Calm, quietude, peace | Faith | Loyalty | Self-reliance |

| Challenge | Faithfulness | Maximum utilization | Self-thinking |

| Change | Family | Intensity (of time, resources) | Sensitivity |

| Charity | Family feeling | Merit | Service (to others, society) |

| Cleanliness, orderliness | Flair | Money | Simplicity |

| Collaboration | Freedom, liberty | Oneness | Skill |

| Commitment | Friendship | Openness | Solving problems |

| Communication | Fun | Other's point of view, inputs | Speed |

| Community | Generosity | Patriotism | Spirit, spirituality in life |

| Competence | Gentleness | Peace, nonviolence | Stability |

| Competition | Global view | Perfection | Standardization |

| Concern for others | Goodwill | Personal growth | Status |

| Connection | Goodness | Perseverance | Strength |

| Content over form | Gratitude | Pleasure | A will to perform |

| Continuous improvement | Hard work | Power | Success, achievement |

| Cooperation | Happiness | Practicality | Systemization |

| Coordination | Harmony | Preservation | Teamwork |

| Creativity | Health | Privacy | Timeliness |

| Customer satisfaction | Honor | Progress | Tolerance |

| Decisiveness | Human-centered | Prosperity, wealth | Tradition |

| Determination | Improvement | Punctuality | Tranquility |

| Delight of being, joy | Independence | Quality of work | Trust |

| Democracy | Individuality | Regularity | Truth |

| Discipline | Inner peace, calm, quietude | Reliability | Unity |

| Discovery | Innovation | Resourcefulness | Variety |

| Diversity | Integrity | Respect for others | Well-being |

| Dynamism | Intelligence | Responsiveness | Wisdom |

| Source | |||

Attitudes

Our attitudes are favorable or unfavorable opinions toward people, things, or situations. Many things affect our attitudes, including the environment we were brought up in and our individual experiences. Our personalities and values play a large role in our attitudes as well. For example, many people may have attitudes toward politics that are similar to their parents, but their attitudes may change as they gain more experiences. If someone has a bad experience around the ocean, they may develop a negative attitude around beach activities. However, assume that person has a memorable experience seeing sea lions at the beach, for example, then he or she may change their opinion about the ocean. Likewise, someone may have loved the ocean, but if they have a scary experience, such as nearly drowning, they may change their attitude.

The important thing to remember about attitudes is that they can change over time, but usually some sort of positive experience needs to occur for our attitudes to change dramatically for the better. We also have control of our attitude in our thoughts. If we constantly stream negative thoughts, it is likely we may become a negative person.

In a workplace environment, you can see where attitude is important. Someone’s personality may be cheerful and upbeat. These are the prized employees because they help bring positive perspective to the workplace. Likewise, someone with a negative attitude is usually someone that most people prefer not to work with. The problem with a negative attitude is that it has a devastating effect on everyone else. Have you ever felt really happy after a great day and when you got home, your roommate was in a terrible mood because of her bad day? In this situation, you can almost feel yourself deflating! This is why having a positive attitude is a key component to having good human relations at work and in our personal lives.

But how do we change a negative attitude? Because a negative attitude can come from many sources, there are also many sources that can help us improve our attitude.

Exercise 2

Exercise 2

Changing Your Attitude

Our attitude is ultimately about how we set our expectations; how we handle the situation when our expectations are not met; and finally, how we sum up an experience, person, or situation. When we focus on improving our attitude on a daily basis, we get used to thinking positively and our entire personality can change. It goes without saying that employers prefer to hire and promote someone with a positive attitude as opposed to a negative one. Other tips for improving attitude include

- When you wake up in the morning, decide you are going to have an excellent day. By having this attitude, it is less likely you may feel disappointed when small things do not go your way.

- Be conscious of your negative thoughts. Keep a journal of negative thoughts. Upon reviewing them, analyze why you had a negative thought about a specific situation.

- Try to avoid negative thinking. Think of a stop sign in your mind that stops you when you have negative thoughts. Try to turn those thoughts into positive ones. For example, instead of saying, “I am terrible in math,” say, “I didn’t do well on that test. It just means I will study harder next time.”

- Spend time with positive people. All of us likely have a friend who always seems to be negative or a coworker who constantly complains. People like this can negatively affect our attitude, too, so steering clear when possible, or limiting the interaction time, is a great way to keep a positive attitude intact.

- Spend time in a comfortable physical environment. If your mattress isn’t comfortable and you aren’t getting enough sleep, it is more difficult to have a positive attitude! Or if the light in your office is too dark, it might be more difficult to feel positive about the day. Look around and examine your physical space. Does it match the mental frame of mind you want to be in?

Source: From Richard Whitaker, “Improving Your Attitude,” Biznick, September 2, 2008, accessed February 3, 2012.

When considering our personality, values, and attitudes, we can begin to get the bigger picture of who we are and how our experiences affect how we behave at work and in our personal lives. It is a good idea to reflect often on what aspects of our personality are working well and which we might like to change. With self-awareness, we can make changes that eventually result in more effective communication and stronger interpersonal relationships.

Let’s Review

Let’s Review

- Personality is defined as a set of traits that predict and explain a person’s behavior. Values are closely interwoven into personality, as our values often define our traits.

- Our personality can help define our attitudes toward specific things, situations, or people. Most people prefer to work with people who have a positive attitude.

- We can improve our attitude by waking up and believing that the day is going to be great. We can also keep awareness of our negative thoughts or those things that may prevent us from having a good day. Spending time with positive people can help improve our own attitude as well.

References

This section is adapted from:

1.2 Personality and Attitude Effects in Human Relations by Saylor Academy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License

2.3 Values and Personality in NSCC Organizational Behaviour by NSCC is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

11.6 Biological Approaches in Psychology 2nd Edition, Rice University OpenStax which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licenseunless otherwise noted.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1996). Effects of impression management and self-deception on the predictive validity of personality constructs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 261–272.

Bouchard, T. J., Lykken, D. T., McGue, M., Segal, N. L., & Tellegen, A. (1990). Sources of human psychological differences: The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart. Science, 250, 223–228.

Bouchard, T., Jr. (1994). Genes, environment, and personality. Science, 264, 1700–1701.

Burger, J. (2008). Personality (7th ed.). Thompson Higher Education.

Buss, D. M. (2009). How can evolutionary psychology successfully explain personality and individual differences? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(4), 359–366.

Carter, S., Champagne, F., Coates, S., Nercessian, E., Pfaff, D., Schecter, D., & Stern, N. B. (2008). Development of temperament symposium. Philoctetes Center, New York.

George, J. M., & Jones, G. R. (1996). The experience of work and turnover intentions: Interactive effects of value attainment, job satisfaction, and positive mood. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 318–325.

Judge, T. A., & Bretz, R. D. (1992). Effects of work values on job choice decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 261–271.

Judge, T. A., & Higgins, C. A. (1999). The Big Five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel Psychology, 52, 621–652.

Kasser, T., Koestner, R., & Lekes, N. (2002). Early family experiences and adult values: A 26-year prospective longitudinal study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 826–835.

Lusk, E. J., & Oliver, B. L. (1974). Research Notes. American manager’s personal value systems-revisited. Academy of Management Journal, 17(3), 549–554.

Ravlin, E. C., & Meglino, B. M. (1987). Effect of values on perception and decision making: A study of alternative work values measures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 666–673.

Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 1–25.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. Free Press.

Rothbart, M. K. (2011). Becoming who we are: Temperament and personality in development. Guilford Press.

Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., & Evans, D. E. (2000). Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(1), 122–135.

Rothbart, M. K., & Derryberry, D. (1981). Development of individual differences in temperament. In M. E. Lamb & A. L. Brown (Eds.), Advances in developmental psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 37–86). Erlbaum.

Rothbart, M. K., Sheese, B. E., Rueda, M. R., & Posner, M. I. (2011). Developing mechanisms of self-regulation in early life. Emotion Review, 3(2), 207–213.

Segal, N. L. (2012). Born together-reared apart: The landmark Minnesota Twin Study. Harvard University Press.

Smola, K. W., & Sutton, C. D. (2002). Generational differences: Revisiting generational work values for the new millennium. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 363–382.

Staw, B. M., Bell, N. E., & Clausen, J. A. (1986). The dispositional approach to job attitudes: A lifetime longitudinal test. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31, 56–77.

Sutin, A. R. & Costa, P. T. (2009). Personality and career success. European Journal of Personality, 23(2), 71–84.

Thomas, A., & Chess, S. (1977). Temperament and development. Brunner/Mazel.