6.3 Putting it All Together: Improving Your Memory

Putting It All Together: Improving Your Memory

A central theme of this chapter has been the importance of the encoding and retrieval processes, and their interaction. To recap: to improve learning and memory, we need to encode information in conjunction with excellent cues that will bring back the remembered events when we need them. But how do we do this? Keep in mind the two critical principles we have discussed: to maximize retrieval, we should construct meaningful cues that remind us of the original experience, and those cues should be distinctive and not associated with other memories. These two conditions are critical in maximizing cue effectiveness (Nairne, 2002).

So, how can these principles be adapted for use in many situations? Let’s go back to how we started the module, with Simon Reinhard’s ability to memorize huge numbers of digits. Although it was not obvious, he applied these same general memory principles, but in a more deliberate way. In fact, all mnemonic devices, or memory aids/tricks, rely on these fundamental principles. In a typical case, the person learns a set of cues and then applies these cues to learn and remember information.

Consider the set of 20 items below that are easy to learn and remember (Bower & Reitman, 1972).

Consider the set of 20 items below that are easy to learn and remember (Bower & Reitman, 1972).

- is a gun. 11 is penny-one, hot dog bun.

- is a shoe. 12 is penny-two, airplane glue.

- is a tree. 13 is penny-three, bumble bee.

- is a door. 14 is penny-four, grocery store.

- is knives. 15 is penny-five, big beehive.

- is sticks. 16 is penny-six, magic tricks.

- is oven. 17 is penny-seven, go to heaven.

- is plate. 18 is penny-eight, golden gate.

- is wine. 19 is penny-nine, ball of twine.

- is hen. 20 is penny-ten, ballpoint pen.

It would probably take you less than 10 minutes to learn this list and practice recalling it several times (remember to use retrieval practice!). If you were to do so, you would have a set of peg words on which you could “hang” memories.

In fact, this mnemonic device is called the peg word technique. If you then needed to remember some discrete items—say a grocery list, or points you wanted to make in a speech—this method would let you do so in a very precise yet flexible way. Suppose you had to remember bread, peanut butter, bananas, lettuce, and so on. The way to use the method is to form a vivid image of what you want to remember and imagine it interacting with your peg words (as many as you need). For example, for these items, you might imagine a large gun (the first peg word) shooting a loaf of bread, then a jar of peanut butter inside a shoe, then large bunches of bananas hanging from a tree, then a door slamming on a head of lettuce with leaves flying everywhere. The idea is to provide good, distinctive cues (the weirder the better!) for the information you need to remember while you are learning it. If you do this, then retrieving it later is relatively easy. You know your cues perfectly (one is gun, etc.), so you simply go through your cue word list and “look” in your mind’s eye at the image stored there (bread, in this case).

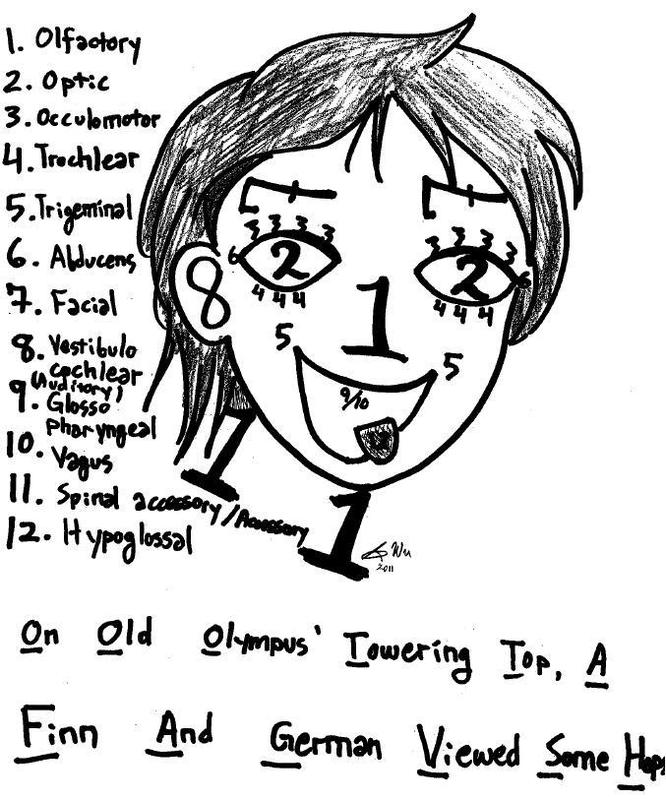

Image Description

Hand-drawn black-and-white cartoon of a smiling head used as a study aid for the 12 cranial nerves. On the left side of the page is a numbered list: 1. Olfactory, 2. Optic, 3. Oculomotor, 4. Trochlear, 5. Trigeminal, 6. Abducens, 7. Facial, 8. Vestibulocochlear (auditory), 9. Glossopharyngeal, 10. Vagus, 11. Spinal accessory/accessory, 12. Hypoglossal. The same numbers are drawn on different parts of the face—nose, eyes and eye muscles, cheeks, ear, mouth, tongue, and neck muscles—to show where each nerve acts. Along the bottom of the page, a handwritten mnemonic phrase reads, “On Old Olympus’ Towering Top, A Finn And German Viewed Some Hops,” with several of the words underlined to cue the order of the cranial nerves.

This peg word method may sound strange at first, but it works quite well, even with little training (Roediger, 1980). One word of warning, though, is that the items to be remembered need to be presented relatively slowly at first, until you have practice associating each with its cue word. People get faster with time. Another interesting aspect of this technique is that it’s just as easy to recall the items in backwards order as forward. This is because the peg words provide direct access to the memorized items, regardless of order.

How did Simon Reinhard remember those digits? Essentially, he has a much more complex system based on these same principles. In his case, he uses “memory palaces” (elaborate scenes with discrete places) combined with huge sets of images for digits. For example, imagine mentally walking through the home where you grew up and identifying as many distinct areas and objects as possible. Simon has hundreds of such memory palaces that he uses. Next, for remembering digits, he has memorized a set of 10,000 images. Every four-digit number for him immediately brings forth a mental image. So, for example, 6187 might recall Michael Jackson. When Simon hears all the numbers coming at him, he places an image for every four digits into locations in his memory palace. He can do this at an incredibly rapid rate, faster than 4 digits per 4 seconds when they are flashed visually, as in the demonstration at the beginning of the module. As noted, his record is 240 digits, recalled in exact order. Simon also holds the world record in an event called “speed cards,” which involves memorizing the precise order of a shuffled deck of cards. Simon was able to do this in 21.19 seconds! Again, he uses his memory palaces, and he encodes groups of cards as single images.

Many books exist on how to improve memory using mnemonic devices, but all involve forming distinctive encoding operations and then having an infallible set of memory cues. We should add that to develop and use these memory systems beyond the basic peg system outlined above takes a great amount of time and concentration. The World Memory Championships are held every year, and the records keep improving. However, for most common purposes, just keep in mind that to remember well you need to encode information in a distinctive way and to have good cues for retrieval. You can adapt a system that will meet most any purpose.

Exercises

Exercises

- Mnemonists like Simon Reinhard develop mental “journeys,” which enable them to use the method of loci. Develop your own journey, which contains 20 places, in order, that you know well. One example might be: the front walkway to your parents’ apartment; their doorbell; the couch in their living room; etc. Be sure to use a set of places that you know well and that have a natural order to them (e.g., the walkway comes before the doorbell). Now you are more than halfway toward being able to memorize a set of 20 nouns, in order, rather quickly. As an optional second step, have a friend make a list of 20 such nouns and read them to you, slowly (e.g., one every 5 seconds). Use the method to attempt to remember the 20 items.

- Recall a recent argument or misunderstanding you have had about memory (e.g., a debate over whether your girlfriend/boyfriend had agreed to something). In light of what you have just learned about memory, how do you think about it? Is it possible that the disagreement can be understood by one of you making a pragmatic inference?

- Think about what you’ve learned in this module and about how you study for tests. On the basis of what you have learned, is there something you want to try that might help your study habits?

References

This chapter was adopted from::

Memory (Encoding, Storage, Retrieval) by Kathleen B. McDermott and Henry L. Roediger III is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Bower, G. H., & Reitman, J. S. (1972). Mnemonic elaboration in multilist learning. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, 478–485.

Nairne, J. S. (2002). The myth of the encoding-retrieval match. Memory, 10, 389–395.

Roediger, H. L. (1980). The effectiveness of four mnemonics in ordering recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 6, 558.