5.5 Learning at Work

Major Influences on Learning

It is possible by way of summary to identify several general factors that can enhance our learning processes. An individual’s desire to learn, background knowledge of a subject, and the length of the learning period are some of the components of a learning environment. Filley et al. (1975) identify five major influences on learning effectiveness.

Drawn largely from behavioral science and psychology literature, substantial research indicates that learning effectiveness is increased considerably when individuals have high motivation to learn. We sometimes encounter students who work day and night to complete a term paper that is of interest to them, whereas writing an uninteresting term paper may be postponed until the last possible minute. Maximum transfer of knowledge is achieved when a student or employee is motivated to learn by a high need to know.

Considerable evidence also demonstrates that we can facilitate learning by providing individuals with feedback on their performance. A knowledge of results serves a gyroscopic function, showing individuals where they are correct or incorrect and furnishing them with the perspective to improve. Feedback also serves as an important positive reinforcer that can enhance an individual’s willingness or desire to learn. Students who are told by their professor how they performed on an exam and what they could do to improve next time are likely to study harder.

In many cases, prior learning can increase the ability to learn new materials or tasks by providing needed background or foundation materials. In math, multiplication is easier to learn if addition has been mastered. These beneficial effects of prior learning on present learning tend to be greatest when the prior tasks and the present tasks exhibit similar stimulus-response connections. For instance, most of the astronauts selected for the space program have had years of previous experience flying airplanes. It is assumed that their prior experience and developed skill will facilitate learning to fly the highly technical, though somewhat similar, vehicles.

Another influence on learning concerns whether the materials to be learned are presented in their entirety or in parts—whole versus part learning (McCormick & Illgen, 1984). Available evidence suggests that when a task consists of several distinct and unrelated duties, part learning is more effective. Each task should be learned separately. However, when a task consists of several integrated and related parts (such as learning the components of a small machine), whole learning is more appropriate, because it ensures that major relationship among parts, as well as proper sequencing of parts, is not overlooked or underemphasized.

The final major influence on learning highlights the advantages and disadvantages of concentrated as opposed to distributed training sessions. Research suggests that distribution of practice—short learning periods at set intervals—is more effective for learning motor skills than for learning verbal or cognitive skills (Bass & Vaughn, 1966; Latham, 1966; Wexley & Latham, 2002). Distributed practice also seems to facilitate learning of very difficult, voluminous, or tedious material. It should be noted, however, that concentrated practice appears to work well where insight is required for task completion. Apparently, concentrated effort over short durations provides a move synergistic approach to problem-solving.

Although there is general agreement that these influences are important (and are under the control of management in many cases), they cannot substitute for the lack of an adequate reinforcement system. In fact, reinforcement is widely recognized as the key to effective learning. If managers are concerned with eliciting desired behaviors from their subordinates, a knowledge of reinforcement techniques is essential.

Applying Theory to the Workplace

When the above principles and techniques of learning are applied to the workplace, we generally see one of two approaches: behavior modification or behavioral self-management. Both approaches rest firmly on the principles of learning described above. Because both of these techniques have wide followings in corporations, we shall review them here. First, we look at the positive and negative sides of behavior modification.

Because of its emphasis on shaping behavior, it is more appropriate to think of behavior modification as a technique for motivating employees rather than as a theory of work motivation. It does not attempt to provide a comprehensive model of the various personal and job-related variables that contribute to motivation. Instead, its managerial thrust is how to motivate, and it is probably this emphasis that has led to its current popularity among some managers. Even so, we should be cautioned against the unquestioned acceptance of any technique until we understand the assumptions underlying the model. If the underlying assumptions of a model appear to be uncertain or inappropriate in a particular situation or organization, its use is clearly questionable.

Organizational Behaviour Management

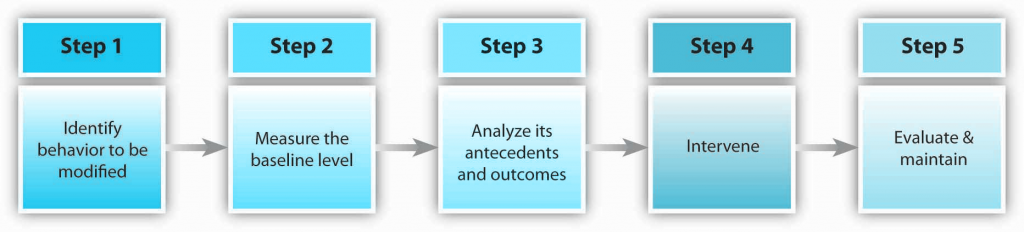

A systematic way in which reinforcement theory principles are applied is called Organizational Behaviour Modification (or OB Mod) (Luthans & Stajkovic, 1999). This is a systematic application of reinforcement theory to modify employee behaviours in the workplace. The model consists of five stages. The process starts with identifying the behaviour that will be modified. Let’s assume that we are interested in reducing absenteeism among employees. In step 2, we need to measure the baseline level of absenteeism. How many times a month is a particular employee absent? In step 3, the behaviour’s antecedents and consequences are determined. Why is this employee absent? More importantly, what is happening when the employee is absent? If the behaviour is being unintentionally rewarded (e.g., the person is still getting paid or is able to avoid unpleasant assignments because someone else is doing them), we may expect these positive consequences to reinforce the absenteeism. Instead, to reduce the frequency of absenteeism, it will be necessary to think of financial or social incentives to follow positive behaviour and negative consequences to follow negative behaviour. In step 4, an intervention is implemented. Removing the positive consequences of negative behaviour may be an effective way of dealing with the situation, or, in persistent situations, punishments may be used. Finally, in step 5 the behaviour is measured periodically and maintained.

Studies examining the effectiveness of OB Mod have been supportive of the model in general. A review of the literature found that OB Mod interventions resulted in 17% improvement in performance (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1997). Particularly in manufacturing settings, OB Mod was an effective way of increasing performance, although positive effects were observed in service organizations as well.

The second managerial technique for shaping learned behavior in the workplace is behavioral self-management (or BSM). Behavioral self-management is the process of modifying one’s own behavior by systematically managing cues, cognitive processes, and contingent consequences (Luthans & Davis, 1979; Luthans & Kreitner, 1985).

BSM is an approach to learning and behavioral change that relies on the individual to take the initiative in controlling the change process. The emphasis here is on “behavior” (because our focus is on changing behaviors), not attitudes, values, or personality. Although similar to behavior modification, BSM differs in one important respect: there is a heavy emphasis on cognitive processes, reflecting the influence of Bandura’s social learning theory.

The Self-Regulation Process

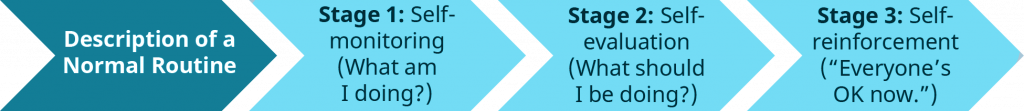

Underlying BSM is a firm belief that individuals are capable of self-control; if they want to change their behavior (whether it is to come to work on time, quit smoking, lose weight, etc.), it is possible through a process called self-regulation, as depicted in Figure 5.7 According to the model, people tend to go about their day’s activities fairly routinely until something unusual or unexpected occurs. At this point, the individual initiates the self-regulation process by entering into self-monitoring (Stage 1). In this stage, the individual tries to identify the problem. For example, if your supervisor told you that your choice of clothing was unsuitable for the office, you would more than likely focus your attention on your clothes.

Next, in Stage 2, or self-evaluation, you would consider what you should be wearing. Here, you would compare what you have on to acceptable standards that you learned from colleagues, other relevant role models, and advertising, for example. Finally, after evaluating the situation and taking corrective action if necessary, you would assure yourself that the disruptive influence had passed and everything was now fine. This phase (Stage 3) is called self-reinforcement. You are now able to return to your normal routine. This self-regulation process forms the foundation for BSM.

Self-Management in Practice

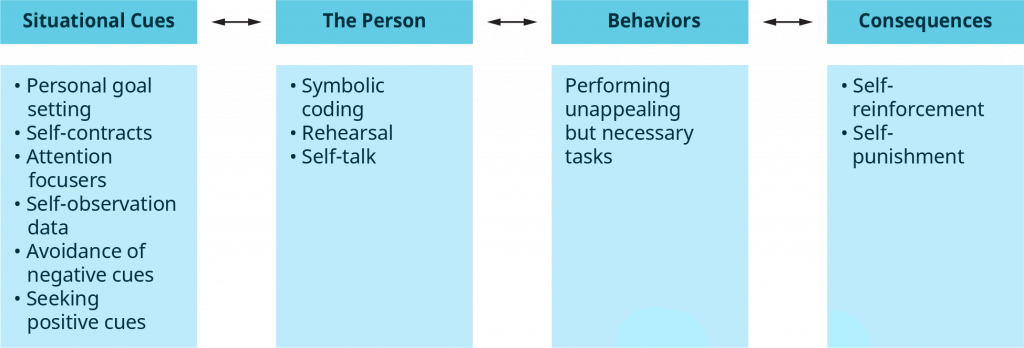

When we combine the above self-regulation model with social learning theory (discussed earlier), we can see how the self-management process works. As shown in Figure 5.7 four interactive factors must be considered. These are situational cues, the person, behaviors, and consequences (Neck & Manz, 2013). (Note that the arrows in this diagram go in both directions to reflect the two-way process among these four factors.)

Situational Cues. In attempting to change any behavior, people respond to the cues surrounding them. One reason it is so hard for some people to give up smoking is the constant barrage of triggers. There are too many cues reminding people to smoke. However, situational cues can be turned to our advantage when using BSM. That is, through the use of six kinds of cue (shown in Figure 5.8 column 1), people can set forth a series of positive reminders and goals concerning the desired behaviors. These reminders serve to focus our attention on what we are trying to accomplish. Hence, a person who is trying to quit smoking would (1) avoid any contact with smokers or other triggers, (2) seek information on the hazards of smoking, (3) set a personal goal of quitting, and (4) keep track of cigarette consumption. These activities are aimed at providing the right situational cues to guide behavior.

Cognitive Supports. Next, the person makes use of three types of cognitive support to assist with the self-management process. Cognitive supports represent psychological (as opposed to environmental) cues. Three such supports can be identified:

- Symbolic Coding. First, people may use symbolic coding, whereby they try to associate verbal or visual stimuli with the problem. For example, we may create a picture in our mind of a smoker who is coughing and obviously sick. Thus, every time we think of cigarettes, we would associate it with illness.

- Rehearsal. Second, people may mentally rehearse the solution to the problem. For example, we may imagine how we would behave in a social situation without cigarettes. By doing so, we develop a self-image of how it would be under the desired condition.

- Self-Talk. Finally, people can give themselves “pep talks” to continue their positive behavior. We know from behavioral research that people who take a negative view of things (“I can’t do this”) tend to fail more than people who take a more positive view (“Yes, I can do this”). Thus, through self-talk, we can help convince ourselves that the desired outcome is indeed possible.

Behavioral Dilemmas. Obviously, self-management is used almost exclusively to get people to do things that may be unappealing; we need little incentive to do things that are fun. Hence, we use self-management to get individuals to stop procrastinating on a job, attend to a job that may lack challenge, assert themselves, and so forth. These are the “behavioral dilemmas” referred to in the model (Figure 5.8). In short, the challenge is to get people to substitute what have been called low-probability behaviors (e.g., adhering to a schedule or forgoing the immediate gratification from one cigarette) for high-probability behaviors (e.g., procrastinating or contracting lung cancer). In the long run, it is better for the individual—and her career—to shift behaviors, because failure to do so may lead to punishment or worse. As a result, people often use self-management to change their short-term dysfunctional behaviors into long-range beneficial ones. This short-term versus long-term conflict is referred to as a behavioral dilemma.

Self-Reinforcement. Finally, the individual can provide self-reinforcement. People can, in effect, pat themselves on the back and recognize that they accomplished what they set out to do. According to Bandura, self-reinforcement requires three conditions if it is to be effective: (1) clear performance standards must be set to establish both the quantity and quality of the targeted behavior, (2) the person must have control over the desired reinforcers, and (3) the reinforcers must be administered only on a conditional basis—that is, failure to meet the performance standard must lead to denial of the reward (Bandura, 1976). Thus, through a process of working to change one’s environment and taking charge of one’s own behavior, self-management techniques allow individuals to improve their behavior in a way that can help them and those around them.

Let’s Focus

Let’s Focus

Reducing Absenteeism through Self-Management

In a well-known study, efforts were made to reduce employee absenteeism using some of the techniques found in behavioral self-management. The employees were unionized state government workers with a history of absenteeism. Self-management training was given to these workers. Training was carried out over eight one-hour sessions for each group, along with eight 30-minute one-on-one sessions with each participant.

Included in these sessions were efforts to (1) teach the participants how to describe problem behaviors (e.g., disagreements with coworkers) that led to absences, (2) identify the causes creating and maintaining the behaviors, and (3) develop coping strategies. Participants set both short-term and long-term goals with respect to modifying their behaviors. In addition, they were shown how to record their own absences in reports including their frequency and the reasons for and consequences of them. Finally, participants identified potential reinforcers and punishments that could be self-administered contingent upon goal attainment or failure.

When, after nine months, the study was concluded, results showed that the self-management approach had led to a significant reduction in absences (compared to a control group). The researchers concluded that such an approach has important applications to a wide array of behavioral problems in the workplace (Lathan & Fayne, 1989).

Exercises

Exercises

- Your manager tells you that the best way of ensuring fairness in reward distribution is to keep the pay a secret. How would you respond to this assertion?

- When distributing bonuses or pay, how would you ensure perceptions of fairness?

- What are the differences between procedural, interactional, and distributive justice? List ways in which you could increase each of these justice perceptions.

- Using examples, explain the concepts of expectancy, instrumentality, and valence.

- Some practitioners and researchers consider OB Mod unethical because it may be viewed as a way of manipulation. What would be your reaction to such a criticism?

References

This section is adapted from:

Chapter 4: Learning and Reinforcement in Organizational Behaviour, Rice University, OpenStax which is licensed under a under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Theories of Motivation in Organizational Behaviour by Saylor Academy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

Bass, B. M. & Vaughn, J. (1966). Training in industry: The management of learning. Wadsworth.

Bandura, A. (1976). Self-reinforcement: theoretical and methodological considerations. Behaviorism, 4(2), 135–155

Filley, A., House, R. J. & Kerr, S. (1975). Managerial process and organizational behavior. Scott, Foresman.

Luthans, F. & Davis, R. (1979). Behavioral self-management—The missing link in managerial effectiveness. Organizational Dynamics, 8, 42-60.

Luthans, F. & Kreitner, R. (1985). Organizational behavior modification and beyond: An operant and social learning approach. Scott, Foresman.

McCormick, E. J. & Illgen, D. (1984). Industrial psychology (8th edition). Prentice-Hall.

Neck, C. C. & Manz, C. P. (2013). Mastering self leadership (6th edition). Pearson.

Wexley, G. & Latham, G. P. (2002). Developing and training human resources in organizations (Third Edition). Prentice Hall.