4.1 Motivation

What inspires employees to provide excellent service, market a company’s products effectively, or achieve the goals set for them? Answering this question is of utmost importance if we are to understand and manage the work behaviour of our peers, subordinates, and even supervisors. Put a different way, if someone is not performing well, what could be the reason?

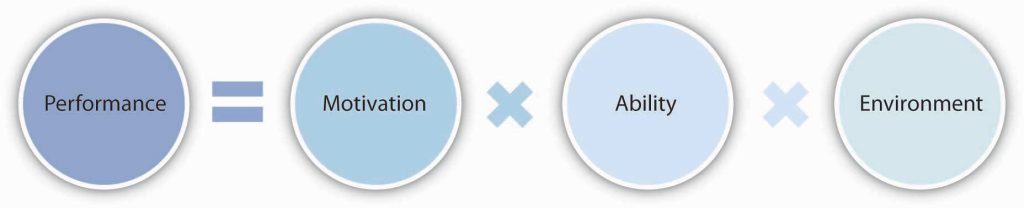

Job performance is viewed as a function of three factors and is expressed with the equation above (Mitchell, 1982; Porter & Lawler, 1968). According to this equation, motivation, ability, and environment are the major influences over employee performance.

Motivation is defined as the desire to achieve a goal or a certain performance level, leading to goal-directed behaviour. Motivation is one of the forces that lead to performance. When we refer to someone as being motivated, we mean that the person is trying hard to accomplish a certain task. Motivation is clearly important if someone is to perform well; however, it is not sufficient.

Ability—or having the skills and knowledge required to perform the job—is also important and is sometimes the key determinant of effectiveness.

Finally, environmental factors such as having the resources, information, and support one needs to perform well are critical to determine performance.

At different times, one of these three factors may be the key to high performance. For example, for an employee sweeping the floor, motivation may be the most important factor that determines performance. In contrast, even the most motivated individual would not be able to successfully design a house without the necessary talent involved in building quality homes. Being motivated is not the same as being a high performer and is not the sole reason why people perform well, but it is nevertheless a key influence over our performance level.

So what motivates people? Why do some employees try to reach their targets and pursue excellence while others merely show up at work and count the hours? As with many questions involving human beings, the answer is anything but simple. Instead, there are several theories explaining the concept of motivation. We will discuss motivation theories under two categories: need-based theories and process theories.

Simply stated, work motivation is the amount of effort a person exerts to achieve a certain level of job performance. Some people try very hard to perform their jobs well. They work long hours, even if it interferes with their family life. Highly motivated people go the “extra mile.” High scorers on an exam make sure they know the examination material to the best of their ability, no matter how much midnight oil they have to burn. Other students who don’t do as well may just want to get by—football games and parties are a lot more fun, after all.

Motivation is of great interest to employers: All employers want their people to perform to the best of their abilities. They take great pains to screen applicants to make sure they have the necessary abilities and motivation to perform well. They endeavor to supply all the necessary resources and a good work environment. Yet motivation remains a difficult factor to manage. As a result, it receives the most attention from organizations and researchers alike, who ask the perennial question “What motivates people to perform well?”

Motivation has two major components: direction and intensity. Direction is what a person wants to achieve, what they intend to do. It implies a target that motivated people try to “hit.” That target may be to do well on a test. Or it may be to perform better than anyone else in a work group. Intensity is how hard people try to achieve their targets. Intensity is what we think of as effort. It represents the energy we expend to accomplish something. If our efforts are getting nowhere, will we try different strategies to succeed? (High-intensity-motivated people are persistent!)

It is important to distinguish the direction and intensity aspects of motivation. If either is lacking, performance will suffer. A person who knows what they want to accomplish (direction) but doesn’t exert much effort (intensity) will not succeed. (Scoring 100 percent on an exam—your target—won’t happen unless you study!) Conversely, people who don’t have a direction (what they want to accomplish) probably won’t succeed either. (At some point, you have to decide on a major if you want to graduate, even if you do have straight As.)

Employees’ targets are sometimes contrary to their employers’, sometimes due to different motivations. Other times because employers do not ensure that employees understand what the employer wants. Employees can have great intensity but poor direction. It is management’s job to provide direction: Should we stress quality as well as quantity? Work independently or as a team? Meet deadlines at the expense of costs? Employees flounder without direction. Clarifying direction results in accurate role perceptions, the behaviours employees think they are expected to perform as members of an organization. Employees with accurate role perceptions understand their purpose in the organization and how the performance of their job duties contributes to organizational objectives. Some motivation theorists assume that employees know the correct direction for their jobs. Others do not. These differences are highlighted in the discussion of motivation theories discussed later in this chapter

At this point, as we begin our discussion of the various motivation theories, it is reasonable to ask, “Why isn’t there just one motivation theory?” The answer is that the different theories are driven by different philosophies of motivation. Some theorists assume that humans are propelled more by needs and instincts than by reasoned actions. These needs-based motivation theories focus on what motivates people. Other theorists focus on the process by which people are motivated. Process motivation theories address how people become motivated—that is, how people perceive and think about a situation. Needs and process theories endeavour to predict motivation in a variety of situations. However, none of these theories can predict what will motivate an individual in a given situation 100 percent of the time. Given the complexity of human behaviour, a “grand theory” of motivation will probably never be developed.

A second reasonable question at this point is “Which theory is best?” If that question could be easily answered, this chapter would be quite short. The simple answer is that there is no “one best theory.” All have been supported by organizational behavior research. All have strengths and weaknesses. However, understanding something about each theory is a major step toward effective management practices.

References

This section is adapted from:

NSCC Organizational Behaviour by NSCC is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

7.1 Motivation: Direction and Intensity in Organizational Behaviour by Rice University OpenStax and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Mitchell, T. R. (1982). Motivation: New directions for theory, research, and practice. Academy of Management Review, 7, 80–88.

Porter, L. W., & Lawler, E. E. (1968). Managerial attitudes and performance. Dorsey Press.