12.2 Ethics

Ethics

Every year there are lapses in ethical judgment by organizations and organizational members. Sadly, these ethical lapses are still frequent in corporate Canada, and they often come with huge lawsuit settlements and/or jail time.

Examples of Ethical Situations

Have you found yourself having to make any of these ethical choices within the last few weeks?

- Cheating on exams

- Downloading music and movies from share sites

- Plagiarizing

- Breaking trust

- Exaggerating experience on a resume

- Using personal websites during company or class time

- Taking office supplies home

- Taking credit for another’s work

- Gossiping

- Lying on time cards

- Conflicts of interest

- Knowingly accepting too much change

- Calling in sick when you aren’t really sick

- Discriminating against people

- Taking care of personal business on company or class time

- Stretching the truth about a product’s capabilities to make the sale

- Divulging private company information

The word “ethics” actually is derived from the Greek word ethos, which means the nature or disposition of a culture (OED, 1963). From this perspective, ethics then involves the moral center of a culture that governs behavior. Without getting too deep, let’s just say that philosophers debate the very nature of ethics, and they have described a wide range of different philosophical perspectives on what constitutes ethics. For our purposes, ethics is the judgmental attachment to whether something is good, right, or just.

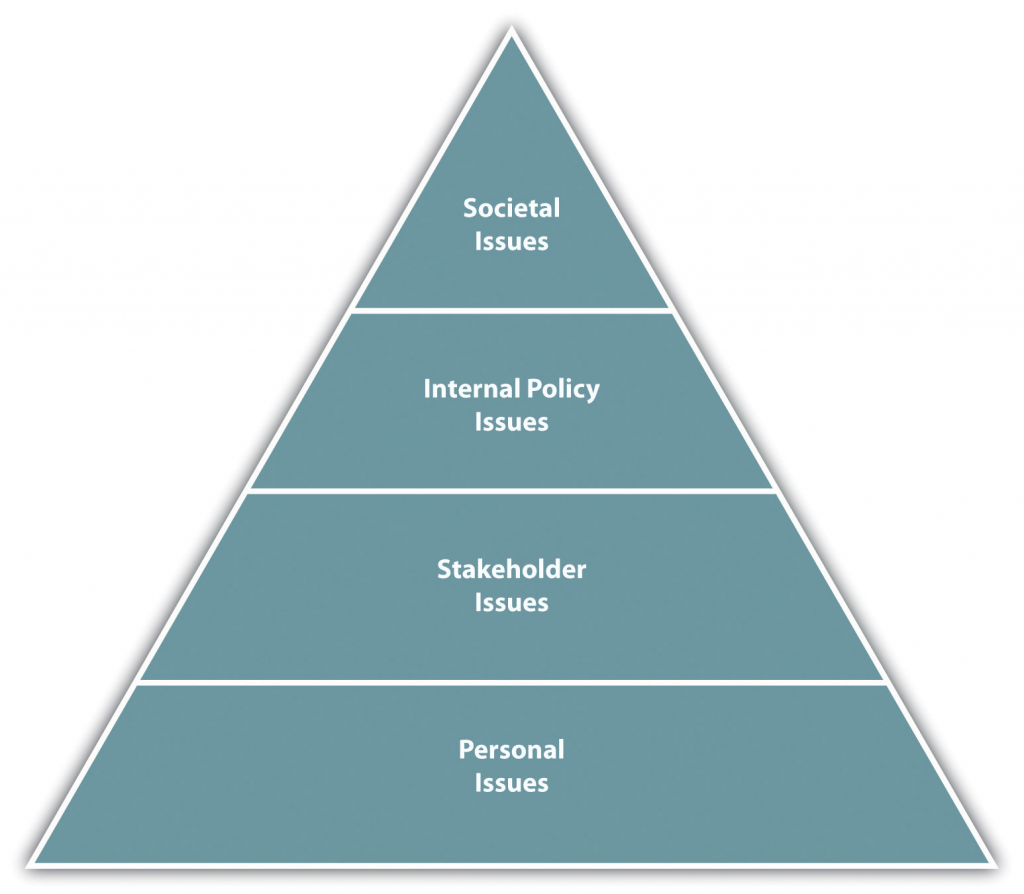

Levels of Ethics

While there may appear to be a difference in ethics between individuals and the organization, often individuals’ ethics are shown through the ethics of an organization, since individuals are the ones who set the ethics to begin with (Brown, 2010). In other words, while we can discuss organizational ethics, remember that individuals are the ones who determine organizational ethics, which ties the conversation of organizational ethics into personal ethics as well. If an organization can create an ethically oriented culture, it is more likely to hire people who behave ethically (Sims, 1991).

There are four main levels of ethical levels within organizations (Roa Rama, 2009). The first level is societal issues. These are the top-level issues relating to the world as a whole, which deal with questions such as the morality of child labor worldwide. Deeper-level societal issues might include the role (if any) of capitalism in poverty, for example. Most companies do not operate at this level of ethics, although some companies, such as Tom’s Shoes, feel it is their responsibility to ensure everyone has shoes to wear. As a result, their “one for one” program gives one pair of shoes to someone in need for every pair of shoes purchased. Concern for the environment, for example, would be another way a company can focus on societal-level issues. Many companies take a stand on societal ethics in part for marketing, but also in part because of the ethics the organization creates due to the care and concern for individuals.

Our second level of ethics is stakeholder’s issues. A stakeholder is anyone affected by a company’s actions. In this level, businesses must deal with policies that affect their customers, employees, suppliers, and people within the community. For example, this level might deal with fairness in wages for employees or notification of the potential dangers of a company’s product.

The third level is the internal policy issue level of ethics. In this level, the concern is internal relationships between a company and employees. Fairness in management, pay, and employee participation would all be considered ethical internal policy issues. If we work in management at some point in our careers, this is certainly an area we will have extensive control over. Creation of policies that relate to the treatment of employees relates to human relations—and retention of those employees through fair treatment. It is in the organization’s best interests to create policies around internal policies that benefit the company, as well as the individuals working for them.

The last level of ethical issues is personal issues. These deal with how we treat others within our organization. For example, gossiping at work or taking credit for another’s work would be considered personal issues. As an employee of an organization, we may not have as much control over societal and stakeholder issues, but certainly we have control over the personal issues level of ethics. This includes “doing the right thing.” Doing the right thing affects our human relations in that if we are shown to be trustworthy when making ethical decisions, it is more likely we can be promoted, or at the very least, earn respect from our colleagues. Without this respect, our human relations with coworkers can be impacted negatively.

One of the biggest ethical challenges in the workplace is when our company’s ethics do not meet our own personal ethics. For example, suppose you believe strongly that child labor should not be used to produce clothing. You find out, however, that your company uses child labour to produce 10 percent of your products. In this case, your personal values do not meet the societal and stakeholder values you find important. This kind of difference in values can create challenges working in a particular organization. When choosing the company or business we work for, it is important to make sure there is a match between our personal values and the values within the organization.

Sources of Personal Ethics

People are not born with a set of values. The values are developed during the aging process. Our values may be influenced by the following:

- Religion. Religion has an influence over what is considered right and wrong. Religion can be the guiding force for many people when creating their ethical framework.

- Culture. Every culture has a societal set of values. Our culture tells us what is good, right, and moral. In some cultures, bribery or “gifts” is the normal way of doing business.

- Media. Advertising shows us what our values “should” be.

- Models. Our parents, siblings, mentors, coaches, and others can affect our ethics today and later in life. The way we see them behave and the things they say affect our values.

- Attitudes. Our attitudes, similar to values, start developing at a young age. As a result, our impression, likes, and dislikes affect ethics, too. For example, someone who spends a lot of time outdoors may feel a connection to the environment and try to purchase environmentally friendly products.

- Experiences. Our values can change over time depending on the experiences we have. For example, if we are bullied by our boss at work, our opinion might change on the right way to treat people when we become managers.

Our personality affects our values, too. For example, we discussed type A personalities and their concern for time. Because of this personality trait, the type A person may value using their time wisely. Aspects of emotional intelligence, which relate to ethics, include self-management, social awareness, and empathy. Lacking social awareness and empathy when it comes to ethics can have disastrous effects.

Sources of Company Ethics

Since we know that everyone’s upbringing is different and may have had different models, religion, attitudes, and experiences, companies create policies and standards to ensure employees and managers understand the expected ethics. These sources of ethics can be based on the levels of ethics, which we discussed earlier. Understanding our own ethics and company ethics can apply to our emotional intelligence skills in the form of self-management and managing our relationships with others. Being ethical allows us to have a better relationship with our supervisors and organizations.

For example, companies create values statements, which explain their values and are tied to company ethics. A values statement is the organization’s guiding principles, those things that the company finds important. A company publicizes its values statements but often an internal code of conduct is put into place in order to ensure employees follow company values set forth and advertised to the public.

The code of conduct is a guideline for dealing with ethics in the organization. The code of conduct can outline many things, and often companies offer training in one or more of these areas:

The code of conduct is a guideline for dealing with ethics in the organization. The code of conduct can outline many things, and often companies offer training in one or more of these areas:

- Sexual harassment policy

- Workplace violence

- Employee privacy

- Misconduct off the job

- Conflicts of interest

- Insider trading

- Use of company equipment

- Company information nondisclosures

- Expectations for customer relationships and suppliers

- Policy on accepting or giving gifts to customers or clients

- Bribes

- Relationships with competition

Some companies have 1-800 numbers, run by outside vendors, that allow employees to anonymously inform about ethics violations within the company. Someone who informs law enforcement of ethical or illegal violations is called a whistleblower. Like a person, a company can have ethics and values that should be the cornerstone of any successful person. Understanding where our ethics come from is a good introduction into how we can make good personal and company ethical decisions. Ethical decision making ties into human relations through emotional intelligence skills, specifically, self-management and relationship management. The ability to manage our ethical decision-making processes can help us make better decisions, and better decisions result in higher productivity and improved human relations.

Ethical Decision-making

Now that we have working knowledge of ethics, it is important to discuss some of the models we can use to make ethical decisions. Understanding these models can assist us in developing our self-management skills and relationship management skills. These models will give you the tools to make good decisions, which will likely result in better human relations within your organization.

Note there are literally hundreds of models, but most are similar to the ones we will discuss. Most people use a combination of several models, which might be the best way to be thorough with ethical decision making. In addition, often we find ethical decisions to be quick. For example, if I am given too much change at the grocery store, I may have only a few seconds to correct the situation. In this case, our values and morals come into play to help us make this decision, since the decision making needs to happen fast.

Philosopher’s Approach

Philosophers and ethicists believe in a few ethical standards, which can guide ethical decision making. First, the utilitarian approach says that when choosing one ethical action over another, we should select the one that does the most good and least harm. For example, if the cashier at the grocery store gives me too much change, I may ask myself, if I keep the change, what harm is caused? If I keep it, is any good created? Perhaps the good created is that I am not able to pay back my friend whom I owe money to, but the harm would be that the cashier could lose his job. In other words, the utilitarian approach recognizes that some good and some harm can come out of every situation and looks at balancing the two.

In the rights approach, we look at how our actions will affect the rights of those around us. So rather than looking at good versus harm as in the utilitarian approach, we are looking at individuals and their rights to make our decision. For example, if I am given too much change at the grocery store, I might consider the rights of the corporation, the rights of the cashier to be paid for something I purchased, and the right of me personally to keep the change because it was their mistake.

The common good approach says that when making ethical decisions, we should try to benefit the community as a whole. For example, if we accepted the extra change in our last example but donated to a local park cleanup, this might be considered OK because we are focused on the good of the community, as opposed to the rights of just one or two people.

The virtue approach asks the question, “What kind of person will I be if I choose this action?” In other words, the virtue approach to ethics looks at desirable qualities and says we should act to obtain our highest potential. In our grocery store example, if given too much change, someone might think, “If I take this extra change, this might make me a dishonest person—which I don’t want to be.”

The imperfections in these approaches are threefold (Santa Clara University, n.d.):

- Not everyone will necessarily agree on what is harm versus good.

- Not everyone agrees on the same set of human rights.

- We may not agree on what a common good means.

Because of these imperfections, it is recommended to combine several approaches discussed in this section when making ethical decisions. We can also consider another, more concrete model of ethical decision-making such as the 12 Questions Model or the 8 steps by Corey et al. (1998). Let’s discuss both of these models in more detail.

The Twelve Questions Model

Laura Nash, an ethics researcher, created the Twelve Questions Model as a simple approach to ethical decision making (Nash, 1981). In her model, she suggests asking yourself questions to determine if you are making the right ethical decision. This model asks people to reframe their perspective on ethical decision making, which can be helpful in looking at ethical choices from all angles. Her model consists of the following questions: Have you defined the problem accurately?

- How would you define the problem if you stood on the other side of the fence?

- How did this situation occur in the first place?

- To whom and what do you give your loyalties as a person and as a member of the company?

- What is your intention in making this decision?

- How does this intention compare with the likely results?

- Whom could your decision or action injure?

- Can you engage the affected parties in a discussion of the problem before you make your decision?

- Are you confident that your position will be as valid over a long period of time as it seems now?

- Could you disclose without qualms your decision or action to your boss, your family, or society as a whole?

- What is the symbolic potential of your action if understood? If misunderstood?

- Under what conditions would you allow exceptions to your stand?

Consider the situation of Catha and her decision to take home a printer cartilage from work, despite the company policy against taking any office supplies home. She might go through the following process, using the Twelve Questions Model:

- My problem is that I cannot afford to buy printer ink, and I have the same printer at home. Since I do some work at home, it seems fair that I can take home the printer ink.

- If I am allowed to take this ink home, others may feel the same, and that means the company is spending a lot of money on printer ink for people’s home use.

- It has occurred due to the fact I have so much work that I need to take some of it home, and often I need to print at home.

- I am loyal to the company.

- My intention is to use the ink for work purposes only.

- If I take home this ink, my intention may show I am disloyal to the company and do not respect company policies.

- The decision could injure my company and myself, in that if I get caught, I may get in trouble. This could result in loss of respect for me at work.

- Yes, I could engage my boss and ask her to make an exception to the company policy, since I am doing so much work at home.

- No, I am not confident of this. For example, if I am promoted at work, I may have to enforce this rule at some point. It would be difficult to enforce if I personally have broken the rule before.

- I would not feel comfortable doing it and letting my company and boss know after the fact.

- The symbolic action could be questionable loyalty to the company and respect of company policies.

- An exception might be ok if I ask permission first. If I am not given permission, I can work with my supervisor to find a way to get my work done without having a printer cartridge at home.

As you can see from the process, Catha came to her own conclusion by answering the questions involved in this model. The purpose of the model is to think through the situation from all sides to make sure the right decision is being made.

As you can see in this model, first an analysis of the problem itself is important. Determining your true intention when making this decision is an important factor in making ethical decisions. In other words, what do you hope to accomplish and who can it hurt or harm? The ability to talk with affected parties upfront is telling. If you were unwilling to talk with the affected parties, there is a chance (because you want it kept secret) that it could be the wrong ethical decision. Also, looking at your actions from other people’s perspectives is a core of this model.

Consider This

Consider This

8 Steps to Ethical Decision Making

There are many models that provide several steps to the decision-making process. One such model was created in the late 1990s for the counseling profession but can apply to nearly every profession from health care to business (Corey et al., 1998). In this model, the authors propose eight steps to the decision-making process:

- Step 1: Identify the problem. Sometimes just realizing a particular situation is ethical can be the important first step. Occasionally in our organizations, we may feel that it’s just the “way of doing business” and not think to question the ethical nature.

- Step 2: Identify the potential issues involved. Who could get hurt? What are the issues that could negatively impact people and/or the company? What is the worst-case scenario if we choose to do nothing?

- Step 3: Review relevant ethical guidelines. Does the organization have policies and procedures in place to handle this situation? For example, if a client gives you a gift, there may be a rule in place as to whether you can accept gifts and if so, the value limit of the gift you can accept.

- Step 4: Know relevant laws and regulations. If the company doesn’t necessarily have a rule against it, could it be looked at as illegal?

- Step 5: Obtain consultation. Seek support from supervisors, coworkers, friends, and family, and especially seek advice from people who you feel are moral and ethical.

- Step 6: Consider possible and probable courses of action. What are all of the possible solutions for solving the problem? Brainstorm a list of solutions—all solutions are options during this phase.

- Step 7: List the consequences of the probable courses of action. What are both the positive and negative benefits of each proposed solution? Who can the decision affect?

- Step 8: Decide on what appears to be the best course of action. With the facts we have and the analysis done, choosing the best course of action is the final step. There may not always be a “perfect” solution, but the best solution is the one that seems to create the most good and the least harm.

Ethics and Communication at Work

From a communication perspective, there are also ethical issues that you should be aware of. W. Charles Redding (1996), the father of organizational communication, broke down unethical organizational communication into six specific categories.

Table 12.1 Redding’s Typology of Unethical Communication

| An organizational communication act is unethical if it is... | Such organizational communication unethically... |

|---|---|

| coercive | abuses power or authority |

| unjustifiably invades others autonomy | |

| stigmatizes dissents | |

| restricts freedom of speech | |

| refuses to listen | |

| uses rules to stifle discussion and complaints | |

| destructive | attacks others self-esteem, reputations, or feelings |

| disregards others values | |

| engages in insults, innuendoes, epithets, or derogatory jokes | |

| uses put-downs, backstabbing, and character assassination | |

| employs so-called truth as a weapon | |

| violates confidentiality and privacy to gain an advantage | |

| withholds constructive feedback | |

| deceptive | willfully perverts the truth to deceive, cheat, or defraud |

| sends evasive or deliberately misleading or ambiguous messages | |

| employs bureaucratic euphemisms to cover up the truth | |

| intrusive | uses hidden cameras |

| taps telephones | |

| employs computer technologies to monitor employee behavior | |

| disregards legitimate privacy rights | |

| secretive | uses silence and unresponsiveness |

| hoards information | |

| hides wrongdoing or ineptness | |

| manipulative/exploitative | uses demagoguery |

| gains compliance by exploiting fear, prejudice, or ignorance | |

| patronizes or is condescending toward others | |

| Reprinted with permission from Wrench, Punyanunt, and Ward’s (2014, Flat World Knowledge) book Organizational communication: Practice, Research, and Theory. Sourse: Interpersonal Communication |

|

Case Study

Case Study

See Appendix A – Being Ethical: Dealing with Conflicts of Interest

References

This section is adapted from:

Be Ethical at Work in Human Relations by Saylor Academy and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Brown, M. (2010). Ethics in organizations. Santa Clara University. http://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/iie/v2n1/

Corey, G., Corey, M . S., & Callanan, P. (1998). Issues and ethics in the helping professions. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

Nash, L. (1981). Ethics without the sermon. Howard Business Review, 59, 79–90, http://www.cs.bgsu.edu/maner/heuristics/1981Nash.htm

Rao Rama, V. S. (2009, April 17). Four levels of ethics. Citeman Network. http://www.citeman.com/5358-four-levels-of-ethical-questions-in-business.html

Redding, W. C. (1996). Ethics and the study of organizational communication: When will we wake up? In J. A. Jaksa & M. S. Pritchard (Eds.), Responsible communication: Ethical issues in business, industry, and the professions (pp.17-40). Hampton Press.

Santa Clara University. (n.d.). A framework for thinking ethically. http://www.scu.edu/ethics/practicing/decision/framework.html

Sims, R. R. (1991). The institutionalization of organizational ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(7), 493–506.

The Oxford English Dictionary. (1963). Ethics. Clarendon Press.