8.3 Theories of Personality

In this Section:

Early Trait Theories

Trait theorists believe personality can be understood via the approach that all people have certain traits, or characteristic ways of behaving. Do you tend to be sociable or shy? Passive or aggressive? Optimistic or pessimistic? Moody or even-tempered? Early trait theorists tried to describe all human personality traits. For example, one trait theorist, Gordon Allport (Allport & Odbert, 1936), found 4,500 words in the English language that could describe people. He organized these personality traits into three categories: cardinal traits, central traits, and secondary traits. A cardinal trait is one that dominates your entire personality, and hence your life—such as Ebenezer Scrooge’s greed and Mother Theresa’s altruism. Cardinal traits are not very common: Few people have personalities dominated by a single trait. Instead, our personalities typically are composed of multiple traits. Central traits are those that make up our personalities (such as loyal, kind, agreeable, friendly, sneaky, wild, and grouchy). Secondary traits are those that are not quite as obvious or as consistent as central traits. They are present under specific circumstances and include preferences and attitudes. For example, one person gets angry when people try to tickle him; another can only sleep on the left side of the bed; and yet another always orders her salad dressing on the side. And you—although not normally an anxious person—feel nervous before making a speech in front of your English class.

In an effort to make the list of traits more manageable, Raymond Cattell (1946, 1957) narrowed down the list to about 171 traits. However, saying that a trait is either present or absent does not accurately reflect a person’s uniqueness, because all of our personalities are actually made up of the same traits; we differ only in the degree to which each trait is expressed. Cattell (1957) identified 16 factors or dimensions of personality: warmth, reasoning, emotional stability, dominance, liveliness, rule-consciousness, social boldness, sensitivity, vigilance, abstractedness, privateness, apprehension, openness to change, self-reliance, perfectionism, and tension (see Table 8.2.). He developed a personality assessment based on these 16 factors, called the 16PF. Instead of a trait being present or absent, each dimension is scored over a continuum, from high to low. For example, your level of warmth describes how warm, caring, and nice to others you are. If you score low on this index, you tend to be more distant and cold. A high score on this index signifies you are supportive and comforting.

Table 8.2 Personality Factors Measured by the 16PF Questionnaire

| Factor | Low Score | High Score |

|---|---|---|

| Warmth | Reserved, detached | Outgoing, supportive |

| Intellect | Concrete thinker | Analytical |

| Emotional stability | Moody, irritable | Stable, calm |

| Aggressiveness | Docile, submissive | Controlling, dominant |

| Liveliness | Somber, prudent | Adventurous, spontaneous |

| Dutifulness | Unreliable | Conscientious |

| Social assertiveness | Shy, restrained | Uninhibited, bold |

| Sensitivity | Tough-minded | Sensitive, caring |

| Paranoia | Trusting | Suspicious |

| Abstractness | Conventional | Imaginative |

| Introversion | Open, straightforward | Private, shrewd |

| Anxiety | Confident | Apprehensive |

| Openmindedness | Closeminded, traditional | Curious, experimental |

| Independence | Outgoing, social | Self-sufficient |

| Perfectionism | Disorganized, casual | Organized, precise |

| Tension | Relaxed | Stressed |

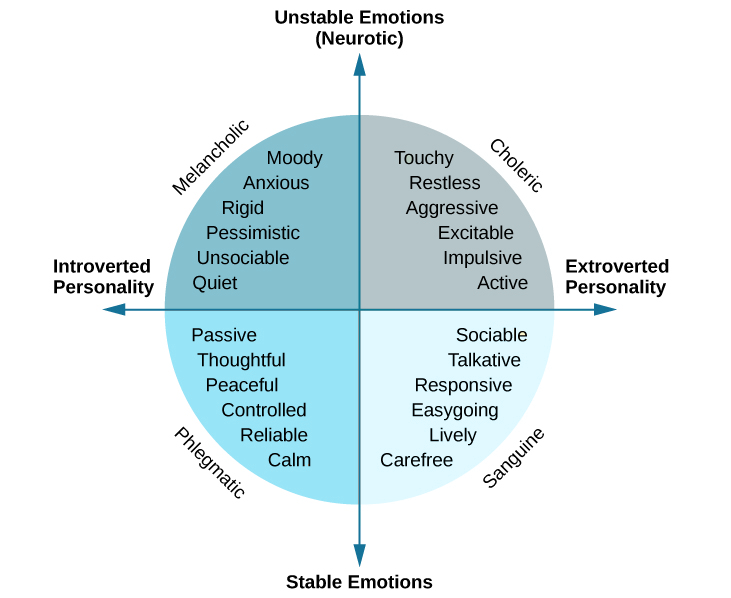

Psychologists Hans and Sybil Eysenck were personality theorists focused on temperament, the inborn, genetically based personality differences that you studied earlier in the chapter. They believed personality is largely governed by biology. The Eysencks (Eysenck, 1990, 1992; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1963) viewed people as having two specific personality dimensions: extroversion/introversion and neuroticism/stability.

According to their theory, people high on the trait of extroversion are sociable and outgoing, and readily connect with others, whereas people high on the trait of introversion have a higher need to be alone, engage in solitary behaviors, and limit their interactions with others. In the neuroticism/stability dimension, people high on neuroticism tend to be anxious; they tend to have an overactive sympathetic nervous system and, even with low stress, their bodies and emotional state tend to go into a flight-or-fight reaction. In contrast, people high on stability tend to need more stimulation to activate their flight-or-fight reaction and are considered more emotionally stable. Based on these two dimensions, the Eysencks’ theory divides people into four quadrants. These quadrants are sometimes compared with the four temperaments described by the Greeks: melancholic, choleric, phlegmatic, and sanguine (see Figure 8.5).

Trait Theory: Big 5 Personality

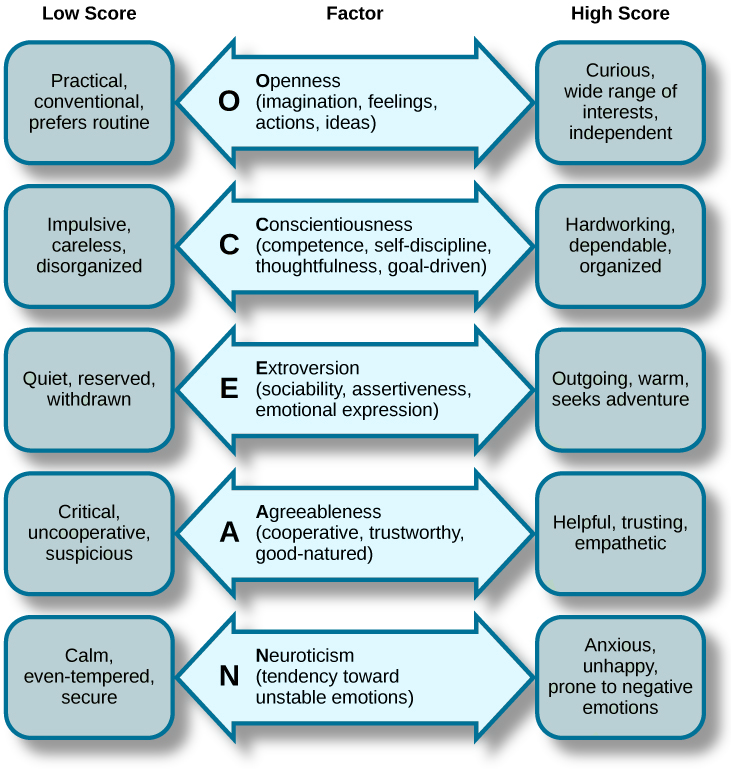

While Cattell’s 16 factors may be too broad, the Eysenck’s two-factor system has been criticized for being too narrow. Another personality theory, called the Five Factor Model, effectively hits a middle ground, with its five factors referred to as the Big Five personality factors. It is the most popular theory in personality psychology today and the most accurate approximation of the basic personality dimensions (Funder, 2001). The five factors are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (see Figure 8.6) A helpful way to remember the factors is by using the mnemonic OCEAN.

The Big Five personality factors each represent a range between two extremes. In reality, most of us tend to lie somewhere midway along the continuum of each factor, rather than at polar ends. It’s important to note that the Big Five factors are relatively stable over our lifespan, with some tendency for the factors to increase or decrease slightly. Researchers have found that conscientiousness increases through young adulthood into middle age, as we become better able to manage our personal relationships and careers (Donnellan & Lucas, 2008). Agreeableness also increases with age, peaking between 50 to 70 years (Terracciano et al., 2005). Neuroticism and extroversion tend to decline slightly with age (Donnellan & Lucas; Terracciano et al.). Additionally, The Big Five factors have been shown to exist across ethnicities, cultures, and ages, and may have substantial biological and genetic components (Jang et al., 1996; Jang et al., 2006; McCrae & Costa, 1997; Schmitt et al., 2007).

Openness is the degree to which a person is curious, original, intellectual, creative, and open to new ideas. People high in openness seem to thrive in situations that require being flexible and learning new things. They are highly motivated to learn new skills, and they do well in training settings (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Lievens et al., 2003). They also have an advantage when they enter into a new organization. Their open-mindedness leads them to seek a lot of information and feedback about how they are doing and to build relationships, which leads to quicker adjustment to the new job (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). When supported, they tend to be creative (Baer & Oldham, 2006). Open people are highly adaptable to change, and teams that experience unforeseen changes in their tasks do well if they are populated with people high in openness (LePine, 2003). Compared to people low in openness, they are also more likely to start their own business (Zhao & Seibert, 2006).

Conscientiousness refers to the degree to which a person is organized, systematic, punctual, achievement oriented, and dependable. Conscientiousness is the one personality trait that uniformly predicts how high a person’s performance will be, across a variety of occupations and jobs (Barrick & Mount, 1991). In fact, conscientiousness is the trait most desired by recruiters and results in the most success in interviews (Dunn et al., 1995; Tay et al. 2006).This is not a surprise, because in addition to their high performance, conscientious people have higher levels of motivation to perform, lower levels of turnover, lower levels of absenteeism, and higher levels of safety performance at work (Judge & Ilies, 2002; Judge et al., 1997; Wallace & Chen, 2006; Zimmerman, 2008). One’s conscientiousness is related to career success and being satisfied with one’s career over time (Judge & Higgins, 1999). Finally, it seems that conscientiousness is a good trait to have for entrepreneurs. Highly conscientious people are more likely to start their own business compared to those who are not conscientious, and their firms have longer survival rates (Certo & Certo, 2005; Zhao & Seibert, 2006).

Extraversion is the degree to which a person is outgoing, talkative, and sociable, and enjoys being in social situations. One of the established findings is that they tend to be effective in jobs involving sales (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Vinchur et al., 1998). Moreover, they tend to be effective as managers and they demonstrate inspirational leadership behaviours (Bauer & Oldham, 2006; Bono & Judge, 2004). Extraverts do well in social situations, and as a result they tend to be effective in job interviews. Part of their success comes from how they prepare for the job interview, as they are likely to use their social network (Caldwell & Burger, 1998; Tay et al., 2006). Extraverts have an easier time than introverts when adjusting to a new job. They actively seek information and feedback, and build effective relationships, which helps with their adjustment (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000).Interestingly, extraverts are also found to be happier at work, which may be because of the relationships they build with the people around them and their relative ease in adjusting to a new job (Judge et al., 2002). However, they do not necessarily perform well in all jobs, and jobs depriving them of social interaction may be a poor fit. Moreover, they are not necessarily model employees. For example, they tend to have higher levels of absenteeism at work, potentially because they may miss work to hang out with or attend to the needs of their friends (Judge et al., 1997).

Agreeableness is the degree to which a person is nice, tolerant, sensitive, trusting, kind, and warm. In other words, people who are high in agreeableness are likeable people who get along with others. Not surprisingly, agreeable people help others at work consistently, and this helping behaviour is not dependent on being in a good mood (Ilies et al., 2006). They are also less likely to retaliate when other people treat them unfairly (Skarlicki et al., 1999). This may reflect their ability to show empathy and give people the benefit of the doubt. Agreeable people may be a valuable addition to their teams and may be effective leaders because they create a fair environment when they are in leadership positions (Mayer et al., 2007). At the other end of the spectrum, people low in agreeableness are less likely to show these positive behaviours. Moreover, people who are not agreeable are shown to quit their jobs unexpectedly, perhaps in response to a conflict they engage with a boss or a peer (Zimmerman, 2008). If agreeable people are so nice, does this mean that we should only look for agreeable people when hiring? Some jobs may actually be a better fit for someone with a low level of agreeableness. Think about it: When hiring a lawyer, would you prefer a kind and gentle person, or a pit bull? Also, high agreeableness has a downside: Agreeable people are less likely to engage in constructive and change-oriented communication (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001). Disagreeing with the status quo may create conflict and agreeable people will likely avoid creating such conflict, missing an opportunity for constructive change.

Neuroticism refers to the degree to which a person is anxious, irritable, aggressive, temperamental, and moody. These people have a tendency to have emotional adjustment problems and experience stress and depression on a habitual basis. People very high in neuroticism experience a number of problems at work. For example, they are less likely to be someone people go to for advice and friendship (Klein et al., 2004). In other words, they may experience relationship difficulties. They tend to be habitually unhappy in their jobs and report high intentions to leave, but they do not necessarily actually leave their jobs (Judge et al., 2002; Zimmerman, 2008). Being high in neuroticism seems to be harmful to one’s career, as they have lower levels of career success (measured with income and occupational status achieved in one’s career). Finally, if they achieve managerial jobs, they tend to create an unfair climate at work (Mayer et al., 2007).

Table 8.3 Summary of MBTI Types

| Dimension | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|

| EI | Extraversion: Those who derive their energy from other people and objects. | Introversion: Those who derive their energy from inside. |

| SN | Sensing: Those who rely on their five senses to perceive the external environment. | Intuition: Those who rely on their intuition and huches to perceive the external environment. |

| TF | Thinking: Those who use their logic to arrive at solutions. | Feeling: Those who use their values and ideas about what is right an wrong to arrive at solutions. |

| JP | Judgment: Those who are organized, systematic, and would like to have clarity and closure. | Perception: Those who are curious, open minded, and prefer to have some ambiguit |

| Source: NSCC Organizational Behaviour by NSCC | ||

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

Aside from the Big Five personality traits, perhaps the most well-known and most often used personality assessment is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Unlike the Big Five, which assesses traits, MBTI measures types. Assessments of the Big Five do not classify people as neurotic or extravert: It is all a matter of degrees. MBTI on the other hand, classifies people as one of 16 types (Carlyn, 1977; Myers, 1962).

In MBTI, people are grouped using four dimensions. Based on how a person is classified on these four dimensions, it is possible to talk about 16 unique personality types, such as ESTJ and ISTP.

MBTI was developed in 1943 by a mother–daughter team, Isabel Myers and Katherine Cook Briggs. Its objective at the time was to aid World War II veterans in identifying the occupation that would suit their personalities. Since that time, MBTI has become immensely popular, and according to one estimate, around 2.5 million people take the test annually. The survey is criticized because it relies on types as opposed to traits, but organizations who use the survey find it very useful for training and team-building purposes. More than 80 of the Fortune 100 companies used Myers-Briggs tests in some form. One distinguishing characteristic of this test is that it is explicitly designed for learning, not for employee selection purposes. In fact, the Myers & Briggs Foundation has strict guidelines against the use of the test for employee selection. Instead, the test is used to provide mutual understanding within the team and to gain a better understanding of the working styles of team members (Leonard & Straus, 1997; Shuit, 2003)

Positive and Negative Affectivity

You may have noticed that behaviour is also a function of moods. When people are in a good mood, they may be more cooperative, smile more, and act friendly. When these same people are in a bad mood, they may have a tendency to be picky, irritable, and less tolerant of different opinions. Yet, some people seem to be in a good mood most of the time, and others seem to be in a bad mood most of the time regardless of what is actually going on in their lives. This distinction is manifested by positive and negative affectivity traits. Positive affective people experience positive moods more frequently, whereas negative affective people experience negative moods with greater frequency. Negative affective people focus on the “glass half empty” and experience more anxiety and nervousness (Watson & Clark, 1984). Positive affective people tend to be happier at work (Ilies & Judge, 2003), and their happiness spreads to the rest of the work environment. As may be expected, this personality trait sets the tone in the work atmosphere. When a team comprises mostly negative affective people, there tend to be fewer instances of helping and cooperation. Teams dominated by positive affective people experience lower levels of absenteeism (George, 1989). When people with a lot of power are also high in positive affectivity, the work environment is affected in a positive manner and can lead to greater levels of cooperation and finding mutually agreeable solutions to problems (Anderson & Thompson, 2004).

Let’s Focus

Let’s Focus

Help, I Work With a Negative Person!

Employees who have high levels of neuroticism or high levels of negative affectivity may act overly negative at work, criticize others, complain about trivial things, or create an overall negative work environment. Here are some tips for how to work with them effectively.

- Understand that you are unlikely to change someone else’s personality. Personality is relatively stable and criticizing someone’s personality will not bring about change. If the behaviour is truly disruptive, focus on behaviour, not personality.

- Keep an open mind. Just because a person is constantly negative does not mean that they are not sometimes right. Listen to the feedback they are giving you.

- Set a time limit. If you are dealing with someone who constantly complains about things, you may want to limit these conversations to prevent them from consuming your time at work.

- You may also empower them to act on the negatives they mention. The next time an overly negative individual complains about something, ask that person to think of ways to change the situation and get back to you.

- Ask for specifics. If someone has a negative tone in general, you may want to ask for specific examples for what the problem is.

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Ferguson, J. (2006, October 31); Karcher, C. (2003, September); Mudore, C. F. (2001, February/March).

Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring refers to the extent to which a person is capable of monitoring his or her actions and appearance in social situations. In other words, people who are social monitors are social chameleons who understand what the situation demands and act accordingly, while low social monitors tend to act the way they feel (Snyder, 1974; Snyder, 1987). High social monitors are sensitive to the types of behaviours the social environment expects from them. Their greater ability to modify their behaviour according to the demands of the situation and to manage their impressions effectively is a great advantage for them (Turnley & Bolino, 2001). In general, they tend to be more successful in their careers. They are more likely to get cross-company promotions, and even when they stay with one company, they are more likely to advance (Day & Schleicher; Kilduff & Day, 1994). Social monitors also become the “go to” person in their company and they enjoy central positions in their social networks (Mehra et al., 2001). They are rated as higher performers, and emerge as leaders (Day et al., 2002). While they are effective in influencing other people and get things done by managing their impressions, this personality trait has some challenges that need to be addressed. First, when evaluating the performance of other employees, they tend to be less accurate. It seems that while trying to manage their impressions, they may avoid giving accurate feedback to their subordinates to avoid confrontations (Jawahar, 2001). This tendency may create problems for them if they are managers. Second, high social monitors tend to experience higher levels of stress, probably caused by behaving in ways that conflict with their true feelings. In situations that demand positive emotions, they may act happy although they are not feeling happy, which puts an emotional burden on them. Finally, high social monitors tend to be less committed to their companies. They may see their jobs as a stepping-stone for greater things, which may prevent them from forming strong attachments and loyalty to their current employer (Day et al., 2002).

Proactive Personality

Proactive personality refers to a person’s inclination to fix what is perceived as wrong, change the status quo, and use initiative to solve problems. Instead of waiting to be told what to do, proactive people take action to initiate meaningful change and remove the obstacles they face along the way. In general, having a proactive personality has a number of advantages for these people. For example, they tend to be more successful in their job searches (Brown et al., 2006). They are also more successful over the course of their careers, because they use initiative and acquire greater understanding of the politics within the organization (Seibert, 1999; Seibert et al., 2001). Proactive people are valuable assets to their companies because they may have higher levels of performance (Crant, 1995). They adjust to their new jobs quickly because they understand the political environment better and often make friends more quickly (Kammeyer-Mueller & Wanberg, 2003; Thompson, 2005). Proactive people are eager to learn and engage in many developmental activities to improve their skills (Major et al., 2006). Despite all their potential, under some circumstances a proactive personality may be a liability for an individual or an organization. Imagine a person who is proactive but is perceived as being too pushy, trying to change things other people are not willing to let go, or using their initiative to make decisions that do not serve a company’s best interests. Research shows that the success of proactive people depends on their understanding of a company’s core values, their ability and skills to perform their jobs, and their ability to assess situational demands correctly (Chan, 2006; Erdogan & Bauer, 2005).

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is a belief that one can perform a specific task successfully. Research shows that the belief that we can do something is a good predictor of whether we can actually do it. Self-efficacy is different from other personality traits in that it is job specific. You may have high self-efficacy in being successful academically, but low self-efficacy in relation to your ability to fix your car. At the same time, people have a certain level of generalized self-efficacy and they have the belief that whatever task or hobby they tackle, they are likely to be successful in it.

Research shows that self-efficacy at work is related to job performance (Bauer et al., 2007; Judge et al., 2007; Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). This relationship is probably a result of people with high self-efficacy setting higher goals for themselves and being more committed to these goals, whereas people with low self-efficacy tend to procrastinate (Phillips & Gully, 1997; Steel, 2007; Wofford et al., 1992). Academic self-efficacy is a good predictor of your GPA, whether you persist in your studies, or drop out of college (Robbins et al., 2004).

Is there a way of increasing employees’ self-efficacy? Hiring people who are capable of performing their tasks and training people to increase their self-efficacy may be effective. Some people may also respond well to verbal encouragement. By showing that you believe they can be successful and effectively playing the role of a cheerleader, you may be able to increase self-efficacy. Giving people opportunities to test their skills so that they can see what they are capable of doing (or empowering them) is also a good way of increasing self-efficacy (Ahearne et al., 2005).

Consider This

Consider This

Ways to Build Your Self-Confidence

Having high self-efficacy and self-esteem are boons to your career. People who have an overall positive view of themselves and those who have positive attitudes toward their abilities project an aura of confidence. How do you achieve higher self-confidence?

- Take a self-inventory. What are the areas in which you lack confidence? Then consciously tackle these areas. Take part in training programs; seek opportunities to practice these skills. Confront your fears head-on.

- Set manageable goals. Success in challenging goals will breed self-confidence, but do not make your goals impossible to reach. If a task seems daunting, break it apart and set mini goals.

- Find a mentor. A mentor can point out areas in need of improvement, provide accurate feedback, and point to ways of improving yourself.

- Don’t judge yourself by your failures. Everyone fails, and the most successful people have more failures in life. Instead of assessing your self-worth by your failures, learn from mistakes and move on.

- Until you can feel confident, be sure to act confident. Acting confident will influence how others treat you, which will boost your confidence level. Pay attention to how you talk and behave, and act like someone who has high confidence.

- Know when to ignore negative advice. If you receive negative feedback from someone who is usually negative, try to ignore it. Surrounding yourself with naysayers is not good for your self-esteem. This does not mean that you should ignore all negative feedback, but be sure to look at a person’s overall attitude before making serious judgments based on that feedback.

Sources: Adapted from information in Beagrie, S. (2006, September 26); Beste, F. J., III. (2007, November–December); Goldsmith, B. (2006, October). Kennett, M. (2006, October); Parachin, V. M. (March 2003, October).

Type A/B Personality

Type A Personality

Research has focused on what is perhaps the single most dangerous personal influence on experienced stress and subsequent physical harm. This characteristic was first introduced by Friedman and Rosenman and is called Type A personality(Friedman & Rosenman, 1974).

Type A and Type B personalities are felt to be relatively stable personal characteristics exhibited by individuals. Type A personality is characterized by impatience, restlessness, aggressiveness, competitiveness, polyphasic activities (having many “irons in the fire” at one time), and being under considerable time pressure. Work activities are particularly important to Type A individuals, and they tend to freely invest long hours on the job to meet pressing (and recurring) deadlines. Type B people, on the other hand, experience fewer pressing deadlines or conflicts, are relatively free of any sense of time urgency or hostility, and are generally less competitive on the job. These differences are summarized in table 8.4

Table 8.4 Profiles of Type A and Type B Personalities

| Type A | Type B | |

|---|---|---|

| Highly competitive | Lacks intense competitiveness | |

| Workaholic | Work only one of many interests | |

| Intense sense of urgency | More deliberate time orientation | |

| Polyphasic behaviour | Does one activity at a time | |

| Strong goal-directedness | More moderate goal-directedness | |

| Source: NSCC Organizational Behaviour by NSCC | ||

Type A personality is frequently found in managers. Indeed, one study found that 60 percent of managers were clearly identified as Type A, whereas only 12 percent were clearly identified as Type B (Howard et al., 1976).

It has been suggested that Type A personality is most useful in helping someone rise through the ranks of an organization. The role of Type A personality in producing stress is exemplified by the relationship between this behaviour and heart disease. Rosenman and Friedman studied 3,500 men over an 8 1/2-year period and found Type A individuals to be twice as prone to heart disease, five times as prone to a second heart attack, and twice as prone to fatal heart attacks when compared to Type B individuals. Similarly, Jenkins (1971) studied over 3,000 men and found that of 133 coronary heart disease sufferers, 94 were clearly identified as Type A in early test scores.

Type A behaviour very clearly leads to one of the most severe outcomes of experienced stress. One irony of Type A is that although this behaviour is helpful in securing rapid promotion to the top of an organization, it may be detrimental once the individual has arrived. That is, although Type A employees make successful managers (and salespeople), the most successful top executives tend to be Type B. They exhibit patience and a broad concern for the ramifications of decisions. The key is to know how to shift from Type A behaviour to Type B.

How does a manager accomplish this? The obvious answer is to slow down and relax. However, many Type A managers refuse to acknowledge either the problem or the need for change, because they feel it may be viewed as a sign of weakness. In these cases, several small steps can be taken, including scheduling specified times every day to exercise, delegating more significant work to subordinates, and eliminating optional activities from the daily calendar. Some companies have begun experimenting with interventions to help reduce job-related stress and its serious health implications.

Self-assessments

Self-assessments

See Appendix B – Assessment: Are you a Type A Personality?

References

This section is adapted from:

11.7 Trait Theories in Psychology, 2nd edition by Rice University, OpenStax and is is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

2.3 Individual Differences: Values and Personality in NSCC Organizational Behaviour by NSCC is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

2.5 Type A/B Personality by Stewart Black; Donald G. Gardner; Jon L. Pierce; and Richard Steers is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Ahearne, M., Mathieu, J., & Rapp, A. (2005). To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 945–955.

Allport, G. W. & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait-names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47(1), i–171. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093360

Anderson, C., & Thompson, L. L. (2004). Affect from the top down: How powerful individuals’ positive affect shapes negotiations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 95, 125–139.

Baer, M., & Oldham, G. R. (2006). The curvilinear relation between experienced creative time pressure and creativity: Moderating effects of openness to experience and support for creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 963–970.

Bauer, T. N., Erdogan, B., Liden, R. C., & Wayne, S. J. (2006). A longitudinal study of the moderating role of extraversion: Leader-member exchange, performance, and turnover during new executive development. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 298–310.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1–26.

Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2004). Personality and transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 901–910.

Brown, D. J., Cober, R. T., Kane, K., Levy, P. E., & Shalhoop, J. (2006). Proactive personality and the successful job search: A field investigation with college graduates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 717–726.

Caldwell, D. F., & Burger, J. M. (1998). Personality characteristics of job applicants and success in screening interviews. Personnel Psychology, 51, 119–136.

Carlyn, M. (1977). An assessment of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Journal of Personality Assessment, 41, 461–473.

Cattell, R. B. (1946). The description and measurement of personality. Harcourt, Brace, & World.

Cattell, R. B. (1957). Personality and motivation structure and measurement. World Book.

Certo, S. T., & Certo, S. C. (2005). Spotlight on entrepreneurship. Business Horizons, 48, 271–274.

Chan, D. (2006). Interactive effects of situational judgment effectiveness and proactive personality on work perceptions and work outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 475–481.

Crant, M. J. (1995). The proactive personality scale and objective job performance among real estate agents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 532–537.

Howard, J.,Cunningham, D., & Rechnitzer, P. (1976). Health patterns associated with Type A behavior: A managerial population. Journal of Human Stress, 24-31.

Day, D. V., & Schleicher, D. J. (2006). Self-monitoring at work: A motive-based perspective. Journal of Personality, 74, 685-714.

Day, D. V., Schleicher, D. J., Unckless, A. L., & Hiller, N. J. (2002). Self-monitoring personality at work: A meta-analytic investigation of construct validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 390–401.

Donnellan, M. B., & Lucas, R. E. (2008). Age differences in the big five across the life span: Evidence from two national samples. Psychology and Aging, 23(3), 558–566.

Dunn, W. S., Mount, M. K., Barrick, M. R., & Ones, D. S. (1995). Relative importance of personality and general mental ability in managers’ judgments of applicant qualifications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 500–509.

Erdogan, B., & Bauer, T. N. (2005). Enhancing career benefits of employee proactive personality: The role of fit with jobs and organizations. Personnel Psychology, 58, 859–891.

Eysenck, H. J. (1990). An improvement on personality inventory. Current Contents: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 22(18), 20.

Eysenck, H. J. (1992). Four ways five factors are not basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13, 667–673.

Eysenck, S. B. G., & Eysenck, H. J. (1963). The validity of questionnaire and rating assessments of extroversion and neuroticism, and their factorial stability. British Journal of Psychology, 54, 51–62.

Friedman, M. & Rosenman, R. (1974). Type A behaviour and your heart. Knopf.

Funder, D. C. (2001). Personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 197–221.

George, J. M. (1989). Mood and absence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 317–324.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The big-five factor structure. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 59, 1216–1229.

Howard, J., Cunningham, D., & Rechnitzer, P. (1976). Health patterns associated with Type A behaviour: A managerial population. Journal of Human Stress, pp. 24–31

Ilies, R., & Judge, T. A. (2003). On the heritability of job satisfaction: The mediating role of personality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 750–759

Ilies, R., Scott, B. A., & Judge, T. A. (2006). The interactive effects of personal traits and experienced states on intraindividual patterns of citizenship behaviour. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 561–575.

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J., & Vernon, P. A. (1996). Heritability of the big five personality dimensions and their facts: A twin study. Journal of Personality, 64(3), 577–591.

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J., Ando, J., Yamagata, S., Suzuki, A., Angleitner, A., Ostendorf, F., Riemann, R., & Spinath, F. (2006). Behavioral genetics of the higher-order factors of the Big Five. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 261–272.

Jawahar, I. M. (2001). Attitudes, self-monitoring, and appraisal behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 875–883.

Jenkins, C. (1971). Psychologic disease and social prevention of coronary disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 284, 244–255.

Judge, T. A., & Higgins, C. A. (1999). The Big Five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel Psychology, 52, 621–652.

Judge, T. A., & Ilies, R. (2002). Relationship of personality to performance motivation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 797–807.

Judge, T. A., Jackson, C. L., Shaw, J. C., Scott, B. A., & Rich, B. L. (2007). Self-efficacy and work- related performance: The integral role of individual differences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 107–127.

Judge, T. A., Livingston, B. A., & Hurst, C. (2012). Do nice guys-and gals- really finish last? The joint effects of sex and agreeableness on income. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(2), 390–407.

Judge, T. A., Martocchio, J. J., & Thoresen, C. J. (1997). Five-factor model of personality and employee absence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 745–755.

Klein, K. J., Beng-Chong, L., Saltz, J. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2004). How do they get there? An examination of the antecedents of centrality in team networks. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 952–963.

Kilduff, M., & Day, D. V. (1994). Do chameleons get ahead? The effects of self-monitoring on managerial careers. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1047–1060.

Leonard, D., & Straus, S. (1997). Identifying how we think: The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and the Hermann Brain Dominance Instrument. Harvard Business Review, 75(4), 114–115.

LePine, J. A. (2003). Team adaptation and postchange performance: Effects of team composition in terms of members’ cognitive ability and personality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 27–39.

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Voice and cooperative behaviour as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with Big Five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 326–336.

Lievens, F., Harris, M. M., Van Keer, E., & Bisqueret, C. (2003). Predicting cross-cultural training performance: The validity of personality, cognitive ability, and dimensions measured by an assessment center and a behaviour description interview. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 476–489.

Major, D. A., Turner, J. E., & Fletcher, T. D. (2006). Linking proactive personality and the Big Five to motivation to learn and development activity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 927–935.

Mayer, D., Nishii, L., Schneider, B., & Goldstein, H. (2007). The precursors and products of justice climates: Group leader antecedents and employee attitudinal consequences. Personnel Psychology, 60, 929–963.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52(5), 509–516.

Mehra, A., Kilduff, M., & Brass, D. J. (2001). The social networks of high and low self-monitors: Implications for workplace performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46, 121–146.

Myers, I. B. (1962). The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Princeton University Press.

Phillips, J. M., & Gully, S. M. (1997). Role of goal orientation, ability, need for achievement, and locus of control in the self-efficacy and goal setting process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 792–802.

Robbins, S. B., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 261–288.

Schmitt, D. P., Allik, J., McCrae, R. R., & Benet-Martinez, V. (2007). The geographic distribution of Big Five personality traits: Patterns and profiles of human self-description across 56 nations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38, 173–212.

Seibert, S. E. (1999). Proactive personality and career success. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 416–427.

Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., & Crant, M. J. (2001). What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Personnel Psychology, 54, 845–874.

Shuit, D. P. (2003). At 60, Myers-Briggs is still sorting out and identifying people’s types. Workforce Management, 82(13), 72–74.

Skarlicki, D. P., Folger, R., & Tesluk, P. (1999). Personality as a moderator in the relationship between fairness and retaliation. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 100–108.

Snyder, M. (1974). Self-monitoring of expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30, 526–537.

Snyder, M. (1987). Public appearances/public realities: The psychology of self-monitoring. Freeman.

Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 240–261.

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 65–94.

Tay, C., Ang, S., & Van Dyne, L. (2006). Personality, biographical characteristics, and job interview success: A longitudinal study of the mediating effects of interviewing self-efficacy and the moderating effects of internal locus of control. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 446–454.

Terracciano A., McCrae R. R., Brant L. J., Costa P. T., Jr. (2005). Hierarchical linear modeling analyses of the NEO-PI-R scales in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Psychology and Aging, 20, 493–506.

Thompson, J. A. (2005). Proactive personality and job performance: A social capital perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1011–1017.

Turnley, W. H., & Bolino, M. C. (2001). Achieving desired images while avoiding undesired images: Exploring the role of self-monitoring in impression management. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 351–360.

Vinchur, A. J., Schippmann, J. S., Switzer, F. S., & Roth, P. L. (1998). A meta-analytic review of predictors of job performance for salespeople. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 586–597.

Wallace, C., & Chen, G. (2006). A multilevel integration of personality, climate, self-regulation, and performance. Personnel Psychology, 59, 529–557.

Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 373–385.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 465–490.

Wofford, J. C., Goodwin, V. L., & Premack, S. (1992). Meta-analysis of the antecedents of personal goal level and of the antecedents and consequences of goal commitment. Journal of Management, 18, 595–615.

Zhao, H., & Seibert, S. E. (2006). The Big Five personality dimensions and entrepreneurial status: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 259–271.

Zimmerman, R. D. (2008). Understanding the impact of personality traits on individuals’ turnover decisions: A meta-analytic path model. Personnel Psychology, 61, 309–348.