7.2 Multisensory Awareness and Design

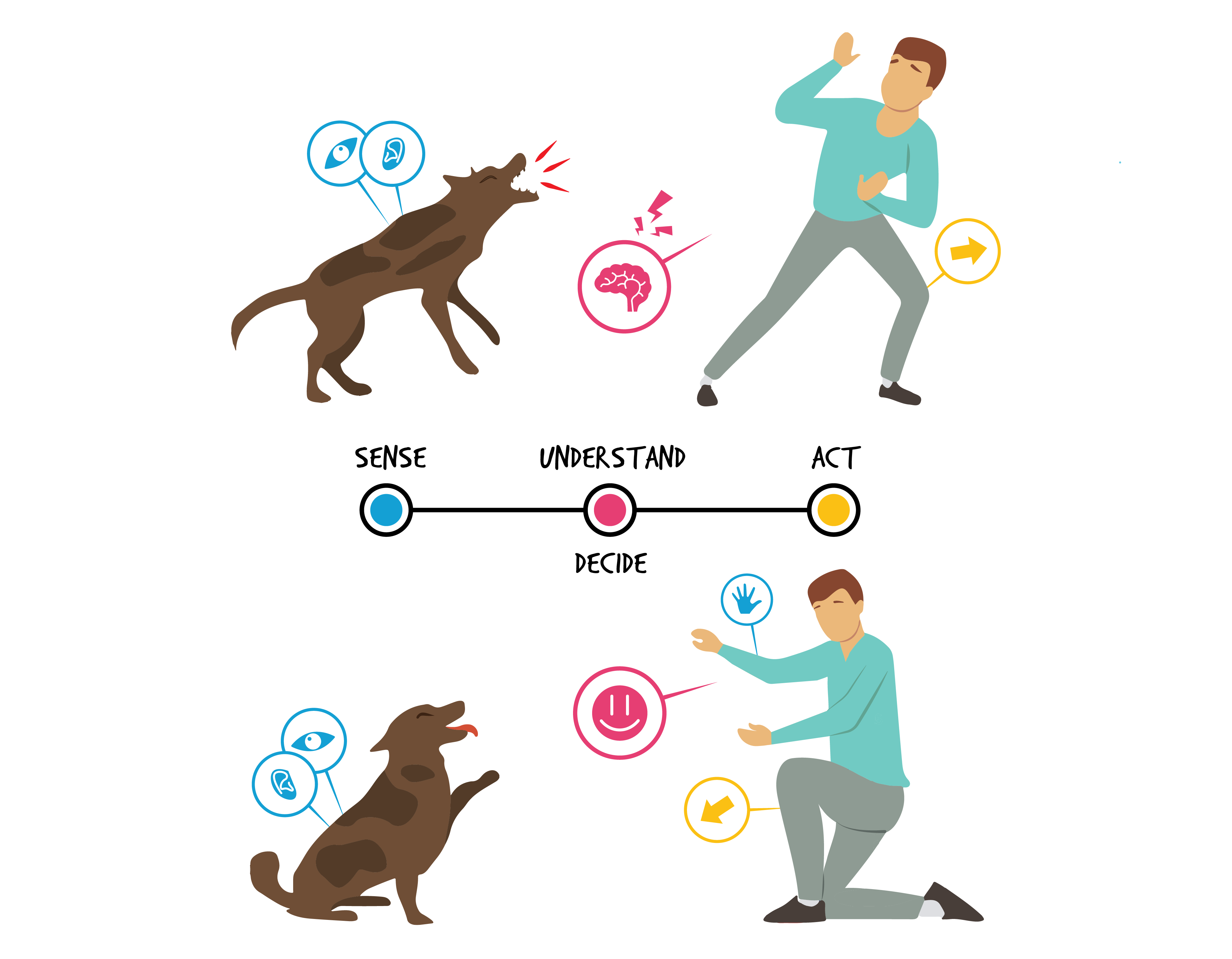

We go through our days, moment by moment responding to different stimuli that keep our brains and nervous systems up-to-date. With every incoming sensory event, we automatically process the stimuli by interpreting, understanding, and deciding how or if we should respond in a particular way (Park & Alderman, 2018). This step-by-step processing of incoming sensory stimuli is part of everyday life. Would you react differently to a barking dog charging at you than to a gentle dog snuggling against your leg? You may either jump out of the way of the barking dog or enjoy petting the gentle dog. In either case, the dog’s behaviour provides multisensory stimulation, as do most events in our surroundings, and each situation prompts a different response that requires us to assess it before taking action.

Responding to sensory stimulation

According to Park & Alderman (2018), the way we perceive all sensory stimulation can be organized into three categories:

- Electromagnetic stimulation that requires physiological reactions, such as pulling our hands out of the way when we see and feel heated electrical elements (relating to vision and touch).

- Mechanical stimulation that involves tensile, compressive, or shearing interactions between physical things that require us to react, such as when we exert pressure to remain upright while windsurfing (relating to sound and touch).

- Chemical stimulation that involves interactions among chemicals, such as when we use toothpaste to clean our teeth (relating to smell and taste).

Categories of sensory stimulation

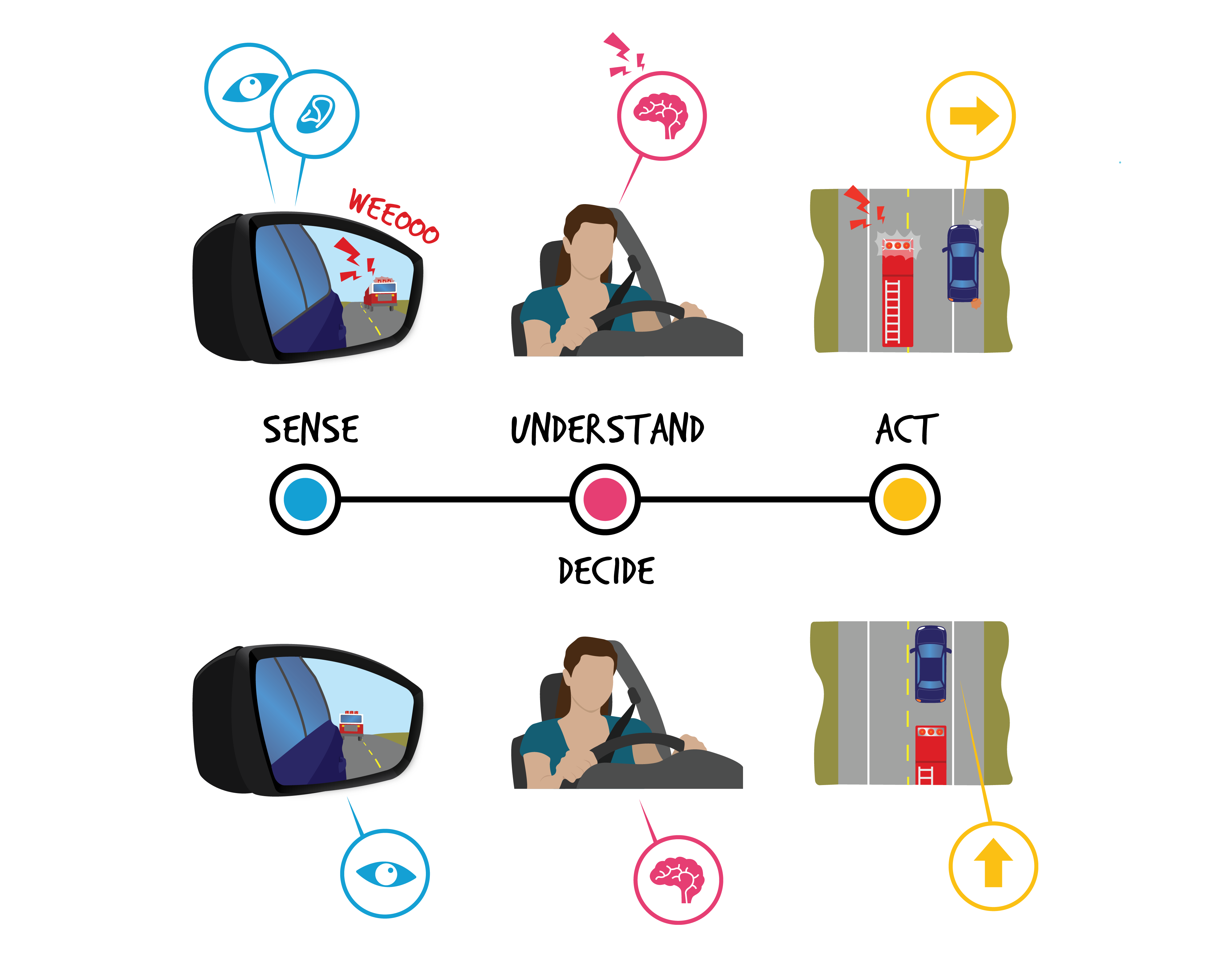

With this awareness, designers can integrate layers of multisensory design features into products, services, or environments that support our abilities to process and react to different kinds of stimuli (Schifferstein & Spence, 2009, Park & Alderman, 2018). For example, think about what happens when you are driving and hear a siren. While driving, you receive concurrent multisensory stimuli providing important information about your surroundings. Perhaps you look at the side and rear-view mirrors and see a fire engine approaching with lights flashing. Usually, this triggers your responsive processes into action. You may quickly pull over or stop to let the fire engine pass. The flashing lights on the firetruck and in the mirrors, the noisy siren, the positioning of the car windows, the rotating steering wheel, the moveable turn signals, the gas pedal, and the brake all support your ability to act appropriately and notify other drivers of your immediate intentions. These sensory electromagnetic (sirens, flashing lights) and mechanical (steering wheel and gas pedal resistance) stimuli are holistically designed to provide you with the opportunity to react appropriately to the context of the situation, as seen below.

Cognitive and MultiSensory Responses to Layers of Stimuli while driving

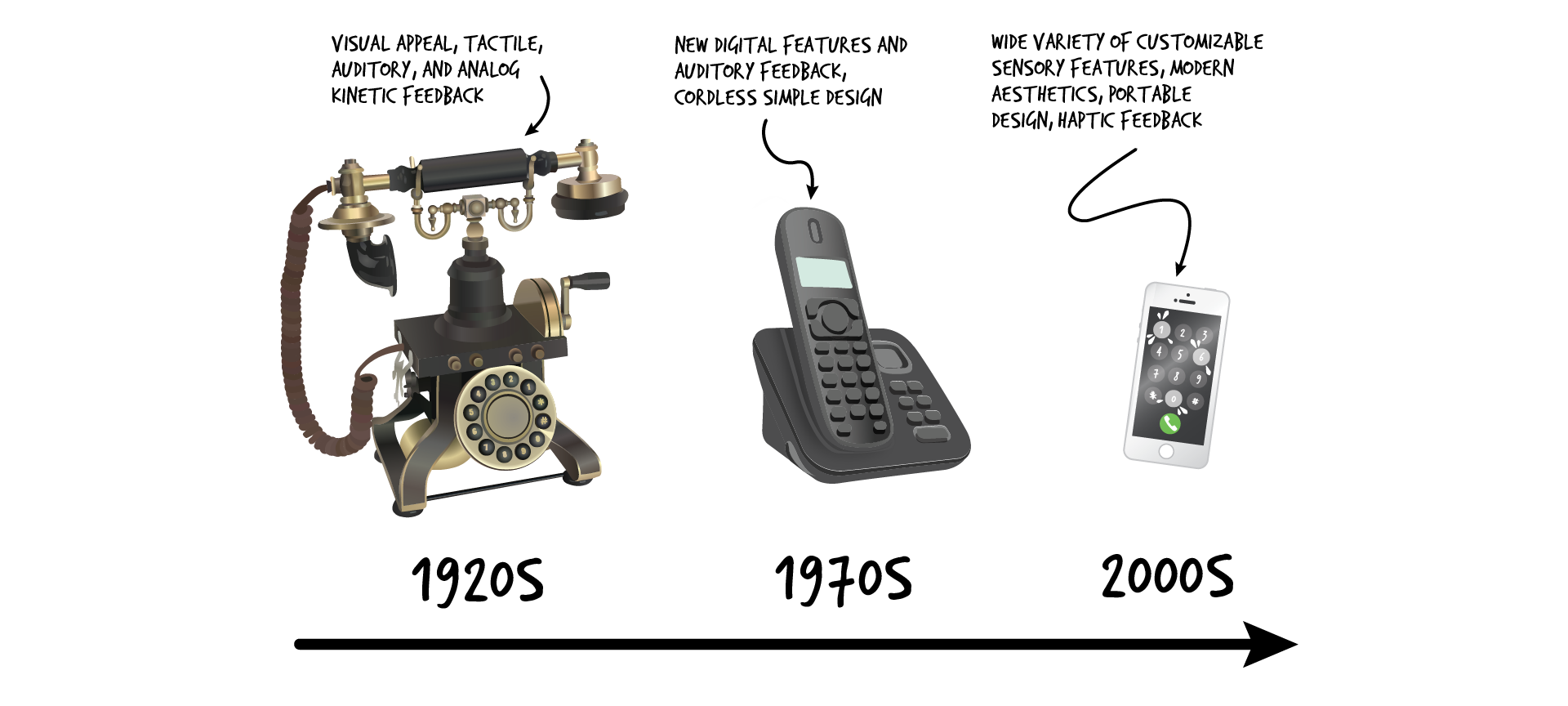

We are learning how to modify design properties to influence the perceived sensory messages that stimulate memories, sensory and motor skills, reflexes, and attention (Schifferstein & Hekkert, 2009, Schifferstein & Spence, 2009; Park & Alderman, 2018). As a result, our devices are changing quickly, with new or more suitable features to improve our quality of life. For example, phone designs continue to evolve by incorporating multisensory modifications into how the devices look, feel, sound, and function. Each upgraded version affects how you listen, hold, and carry the device, physically engage with its interactive features, and even where you can most comfortably use it (in the sun or shade, in noisy or quiet surroundings). All the sensory information we receive when interacting with our products affects our perception, cognition, experience, and behaviour. For example, today many persons with disabilities are experiencing newfound independence through a variety of multisensory and accessible features that were only a dream a decade ago!

Evolution of the phone

Did you know that phones also have a significant cultural impact on us? That they have changed how we live? As you know, our phones are no longer solely communication devices. They organize details about friends, family, and events that effectively replace our need to remember information – by capturing and storing text, images, music, and videos. Each of us can customize our phones to our personal sensory preferences, like ring tones or vibrations when a call or message arrives. Most of us, to various degrees, depend on these features. Indeed, we are even attached to our phones in multisensory ways that often define our personalities, by leveraging design and emotion concepts like ideo- and socio-pleasure, as discussed in Chapter 1.

Changing cultural impacts: Capturing our experiences with our phones

Park & Alderman (2018) believe that people, places, and things become a part of our unique everyday worldview because of our sensory experiences with them – for many of us, seeing, touching, and interacting with something makes it real. In other words, physical evidence builds trust in products, brands, and relationships. That is why rich, multisensory experiences provide more opportunities for engagement.

From lipstick to bicycles, designers incorporate layers of sensory features that go well beyond how a product looks and feels. Consider how the auditory click of a deodorant stick opening and closing provides assuring feedback that the deodorant will remain inside a cleverly designed and easy-to-use container – rich in colour, form, and function. In the design of bicycles, design teams optimize materials and mechanical actions to maximize the gentle swishing sounds of smooth bicycle movements in the kinetic performance of the brakes, wheels, and gears, the tactile comfort of the seat, and the colourful surface finishes and to minimize the tactile vibrations through the handlebars (steel vibrates less than aluminum). All of these features contribute to a product’s multisensory aesthetics.

Layers of multisensory features across products