6.6 Design and Taste

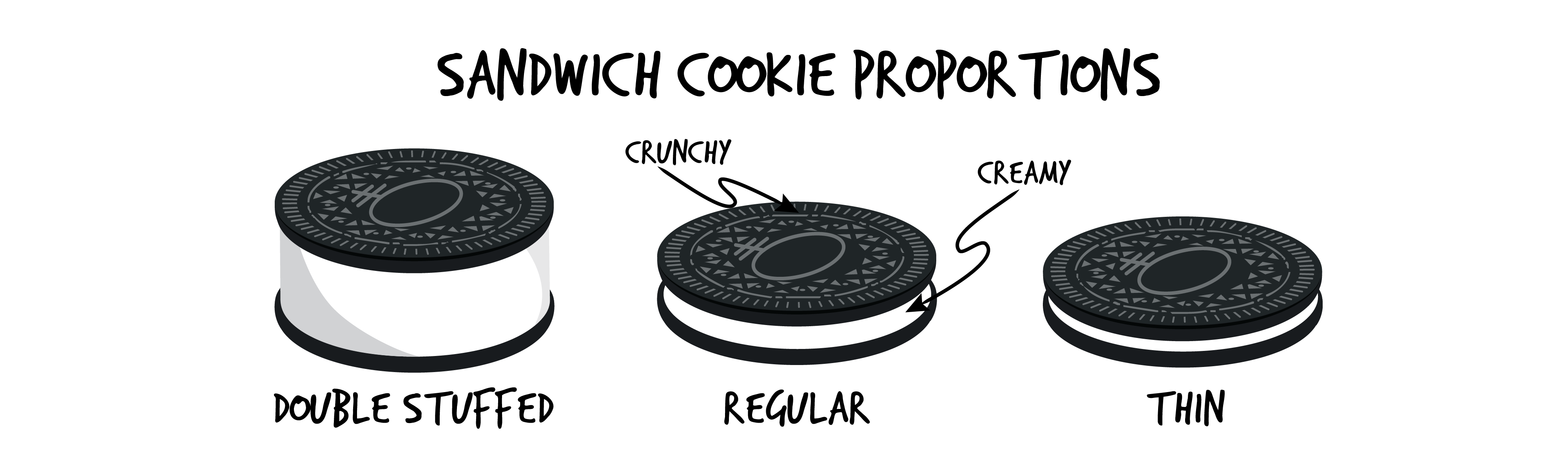

The food industry leverages the concept of providing sensory contrast in a product as another way to maximize multisensory product impact, as the experience of eating Oreo cookies demonstrates. Kessler (2009) dissects the appealing components of the ubiquitous Oreo cookie texture and mouthfeel, and the unique combination of bitter and sweet. He says that these cookies are designed to stimulate our cravings for more. First, we experience the crumbly texture and bitter taste of the chocolate wafer. Next, the smooth texture and sweet taste of the interior icing melts in our mouth and leaves us longing for another sensory stimulus. Even the proportions of one element to another are intentional.

Every detail of your oreo cookie has been designed to enhance its appeal

Contrasts of mouthfeel and flavour combinations are called dynamic novelty in the food industry. “High levels of fat generate easy mouth-melt, and surface variations add a level of interest… Heightened complexity is the key to modern food design” (Kessler, D., 2009).

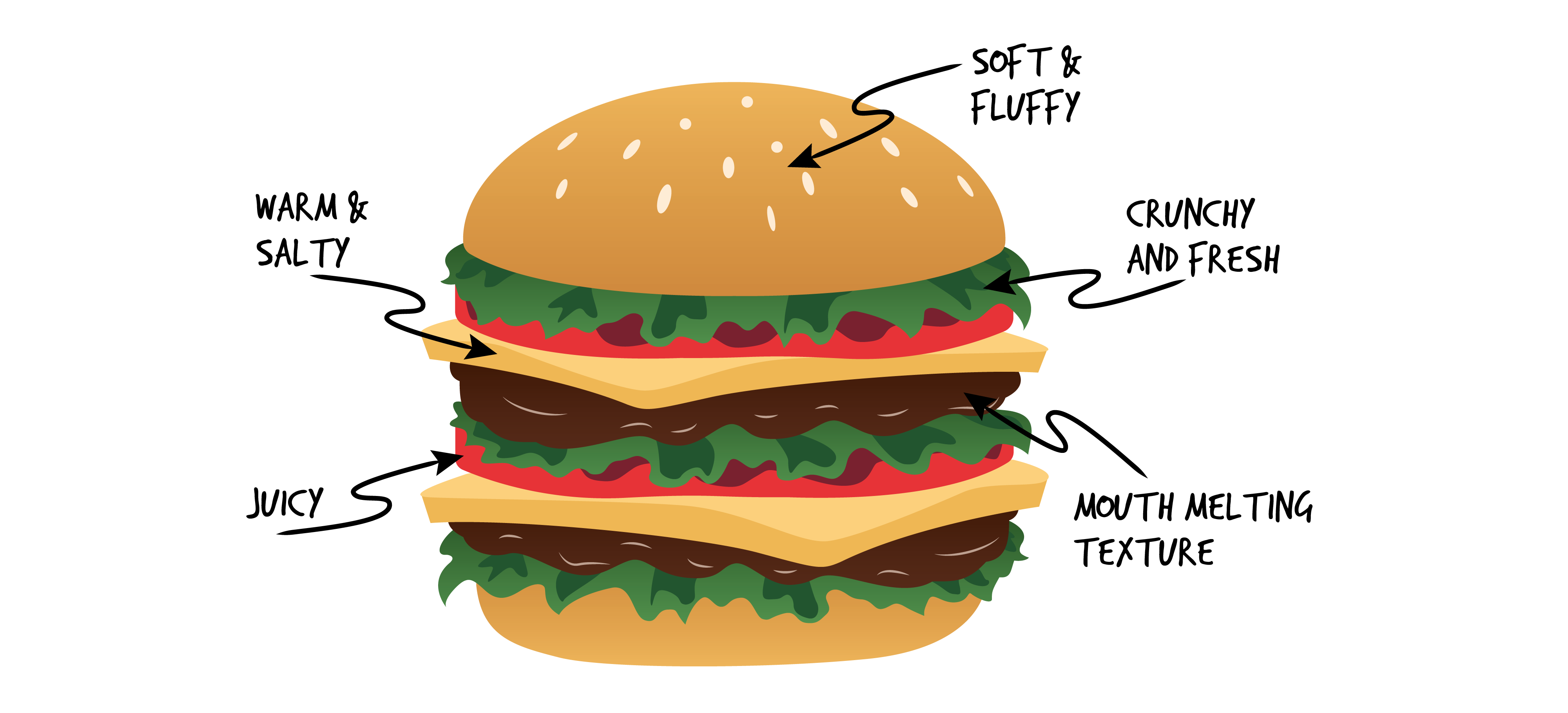

Your commercial hamburger ingredients are designed to provide stimulating dynamic novelty

For Kessler, the hedonic (pleasure-oriented) experience of modern food design should include the following factors:

- an emotional aspect that stimulates anticipation of the taste experience.

- a visually appealing appearance.

- a pleasing aroma.

- an interesting taste and flavour composition.

- a range of oral textures and mouthfeel.

As you may see food design is related to product design and can draw upon many industrial design skill sets such as determining form and colour properties, selecting materials, providing auditory feedback, and designing tactile features. Schifferstein (2021) is interested in how designers can enhance the aesthetic experience of consuming food by systematically engaging multimodal sensations. His description of a food experience journey compliments Kessler’s above. The stages of interaction with food products starts with conjuring up thoughts or memories about a food’s taste, engaging with it at a distance by seeing or smelling it, having closer interactions by touching it, and eventually eating the food. He believes that designers can support the quality of these experiences at each stage along the way.

Food and Design

In view of the stages of a food experience, we get an idea of the part design can play in this multisensory experience. From Schifferstein’s perspective (2021, p. 115), “the physical food may function as the centrepiece, [and] … several supporting elements may be recruited in shaping the intended consumer experience, involving considerations of how the food is prepared and presented (e.g., cooking utensils, packaging, spatial arrangement, tableware) and the context in which it is consumed (e.g., on the street, at a particular occasion, in a restaurant)”.

Designers are already involved in the design of utensils, tools, containers, and cooking ware in which food is kept or processed. Even if these things do not have any intentional flavours, their materials, shapes, and temperature resistance may affect the taste of the foods they interact with. In addition, some utensils, containers and tableware may be designed to influence people’s behaviours. For example, Canadian designer, Diane LeClair Bisson (2020) explored how tableware design could influence behaviour change for children in hospitals who experience a loss of appetite due to their illness. She found that by designing a set of playful mix-and-match bowls, the children’s senses of taste were affected positively and they were more likely to eat.

As another example, lunch boxes can be designed to support Canada’s Food Guide as a way to teach children the proper proportions of foods in a healthy diet. Lunch box size and materials also influence the ability to separate flavours and contain foods with different consistencies. This illustrates the value of design in influencing good eating behaviours, such as eating more healthy foods, reducing food waste, and supporting good food hygiene practices (Bordewijk & Schifferstein, 2020).

Lunchboxes can be designed as tools for learning about healthy eating

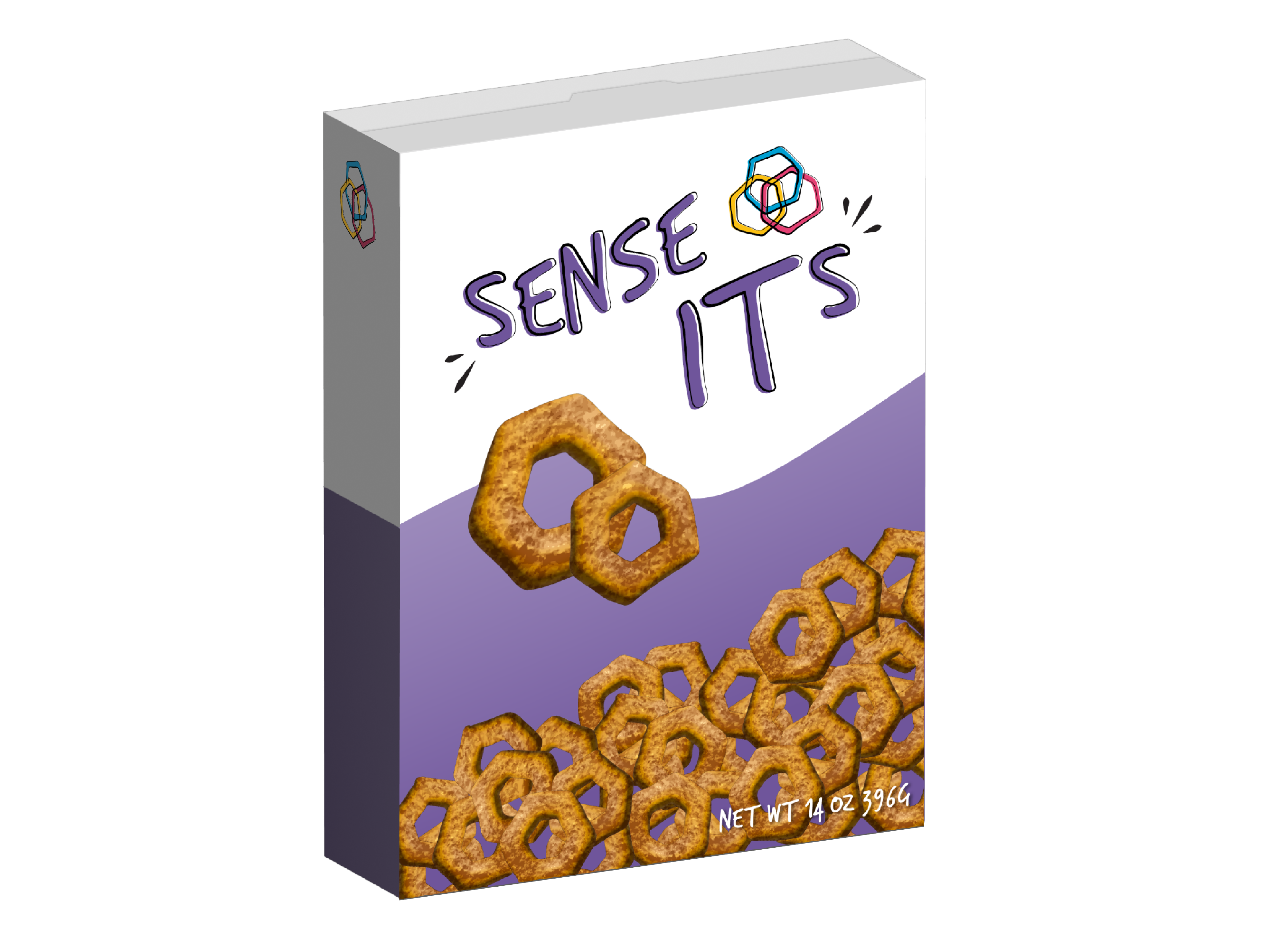

Food packaging designers have also been involved with the food industry for quite some time. Their task is to apply the visual design principles discussed in earlier chapters to communicate the sensory properties of the food inside. They do this through graphic design applications of form, colour, imagery, typography, and materials to attract or possibly even repel consumers (Maffei and Schifferstein, 2017, p. 143).

visual design principles are applied in food packaging design to communicate a message to consumers

Another area where design can contribute to an apparent change in perceived taste is in scented food packaging which is used to enhance the perceived flavour of the food. This is the process of referred olfaction, which means that the addition of a pleasant smell in the package can stimulate our olfactory sense in a way that increases our taste experiences. Referred olfaction played an unusual part in Jessie Thavonekham’s (2015) Master’s thesis in the School of Industrial Design at Carleton University. She invited participants to eat plain unflavoured yoghurt with fruit, from two different types of containers. One was a paper cup and the other was a gelatinous agar cup. In both cases, volunteers perceived a vanilla scent, although none was present. She concluded that the participants had assumed the yoghurt was vanilla-flavoured and due to referred olfaction transferred their expectations into perceptions of sweetness.

We know that many products that industrial designers develop are not meant to be eaten, such as vacuum cleaners, hairdryers, X-Ray Machines, car interiors, and portable drills. However, as we have already noted, designers have a wide range of skills that can be leveraged to enhance multimodal taste experiences. Thinking broadly, there are a number of products that people put into their mouths where taste can be affected by the choice of materials, textures, smells, and sounds. These include baby soothers and baby bottles, coffee cups, dental floss, flutes, snorkels, toothbrushes, and water bottles. Have you ever noticed if your water bottle always tastes the same? If not, how does your taste experience change over time and what features contribute to that change – temperature, texture, smell, or appearance? What part does the water play, or what you put into the water, or what you ate before drinking?

You may not have realized how much attention to your sensory perception goes into the design of your food experiences. For designers interested in food, there are many opportunities for different types of design activities: “design about food, design with food, design for food, food space design, food product design and eating design” (Zampollo, 2015, p. 111). Many of these food design areas are inherently multisensory; layers of sensory stimulation determine the flavour of a good user experience.