6.5 Experiencing Taste

The flavour of food, sometimes simply called the taste, includes the oral sensations of taste (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami) and the nasal sensations of smell. As you learned earlier, the sensation of orthonasal olfaction results from smells entering the front of your nostrils, and the sensation of retronasal olfaction occurs when food vapours rise up the back of your throat as you chew and swallow your food (Cardello & Wise, 2008; Christodulaki, 2020). These contribute to your experience of taste (Schifferstein et al, 2020), even though you may not be aware of the taste-smell interactions that affect your perception of taste (Burdach et al, 1984).

Retronasal Olfaction: food vapours rise up the back of your throat as you chew and swallow your food

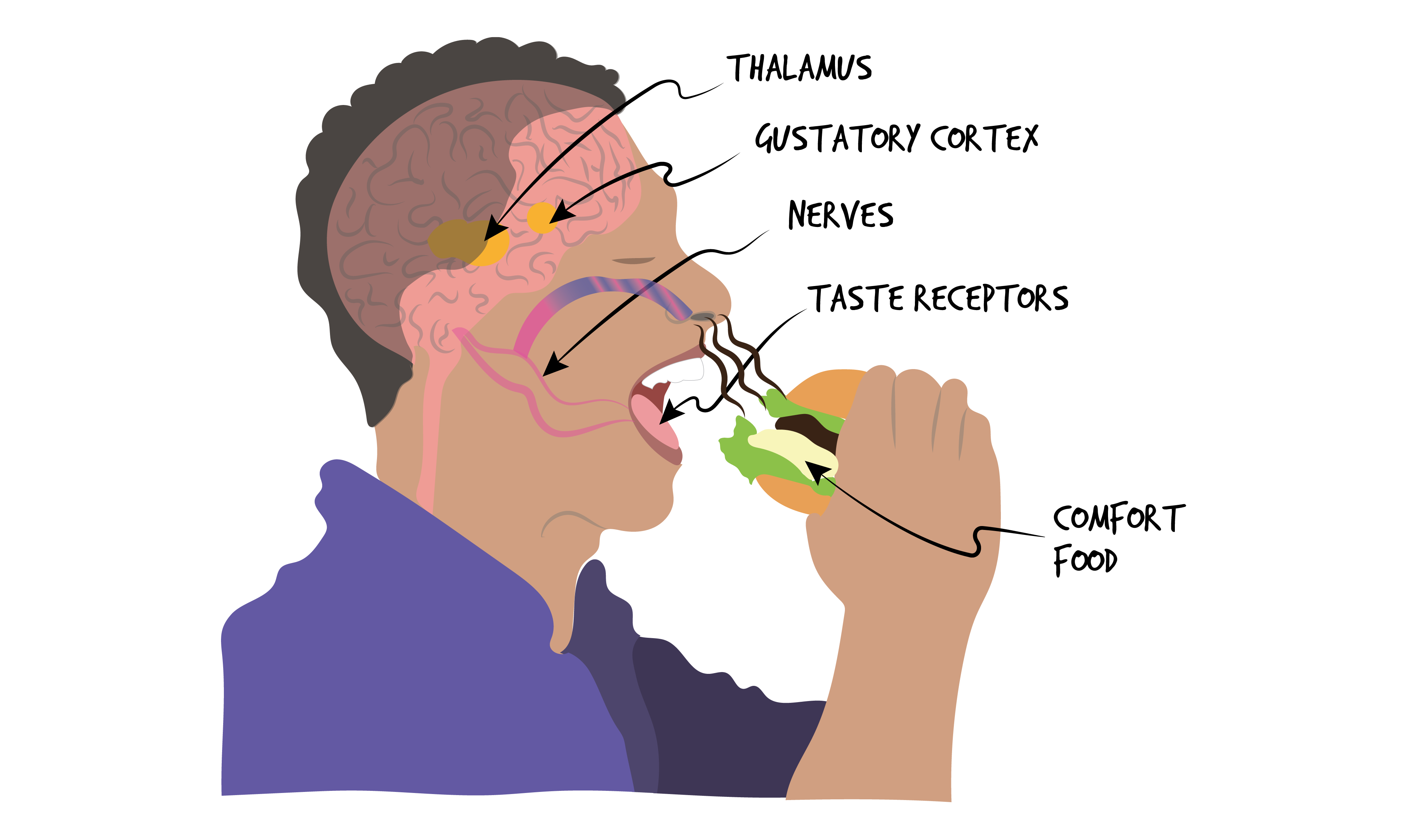

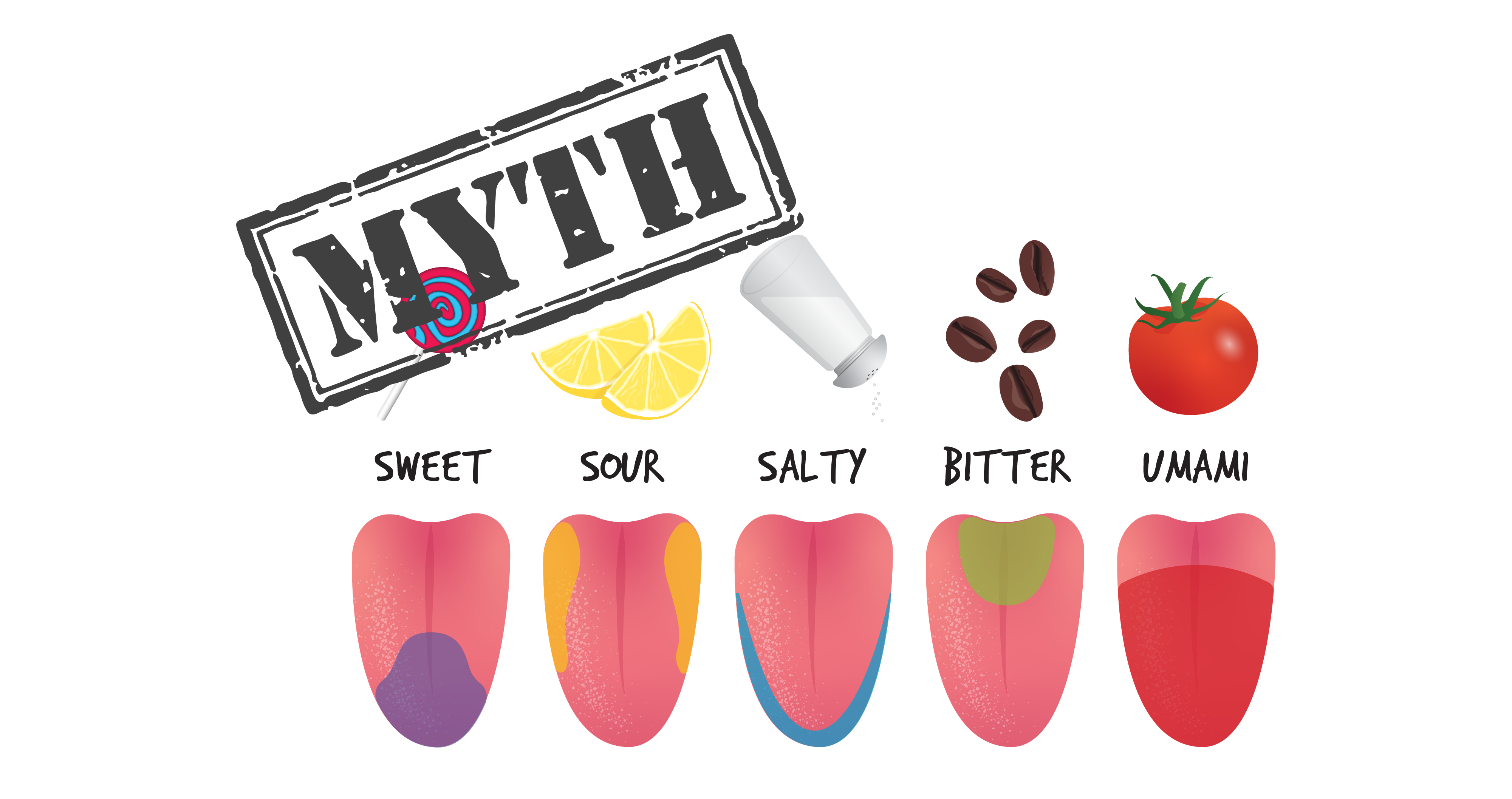

You have thousands of taste buds in your mouth (along your tongue, the roof of your mouth, and the lining of your throat) that respond to the chemicals in food and drink. They distinguish the five taste qualities (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami) that send separate signals to the brain, which identifies them as different tastes (Lupton 2018, National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders, 2022, Schifferstein et al, 2020). Umami may be the least familiar taste sensation; it is a satisfying savoury flavour, most often associated with Japanese food and enhanced by monosodium glutamate (japan-taste.com).

The five tastes are experienced all over the tongue and were once believed to be at specific locations as shown above (adapted from Christodoulaki, 2020)

You perceive the five tastes as flavours through a combination of three kinds of sensations in the brain: 1. the five taste qualities; 2. the chemical sensitivity of your skin and mucous membranes in the oronasal cavities that recognize cool and burning properties of chemicals (these properties, such as mint or chilli peppers are perceived as pungency, irritation, or burning); and 3. your perceptions of the tactile sensations of heat, cold, and texture. You then acknowledge these taste signals as the flavours of what you are eating – pizza, apple pie, or a grape (atlas of science.org, 2023).

Your flavour perceptions can also be a fleeting sensory experience similar to your perception of smells. Taste adaptation is like olfactory fatigue in which the sense of taste grows weaker over time as its perceived intensity decreases (Cardello & Wise, 2008, Schifferstein et al, 2020). In other words, after about one minute, the sense of a unique taste disappears. For example, have you ever noticed that the first bite of a chocolate bar seems to have the most chocolatey flavour and subsequent bites are less flavourful? Try it. Another thing you can try to pay attention to is how the taste of one thing can influence what the next thing tastes like. What about when you eat something just after brushing your teeth? You may think that the taste of the toothpaste changed the taste of your apple, but research has found that the effects of the toothpaste actually changed your apple’s perceived smell, leading you to sense that it tasted different (Cardello & Wise, 2008).

Taste is Multisensory

According to Lupton (2018, p. 66), flavour engages all the senses, “Texture (touch), aroma (smell) temperature (touch), and appearance (sight) as well as language and memory, [which] all contribute to the complex experience of flavour”. She considers flavour as primal because the brainstem is involved in triggering our responses to tastes, which can be either attraction or repulsion. These primal reactions may respond to sensory properties that protect you from poison or toxins, such as aversion to the smell of spoiling meat, the look of mouldy berries, or the feel of slimy vegetables (di Cicco et al, 2021).

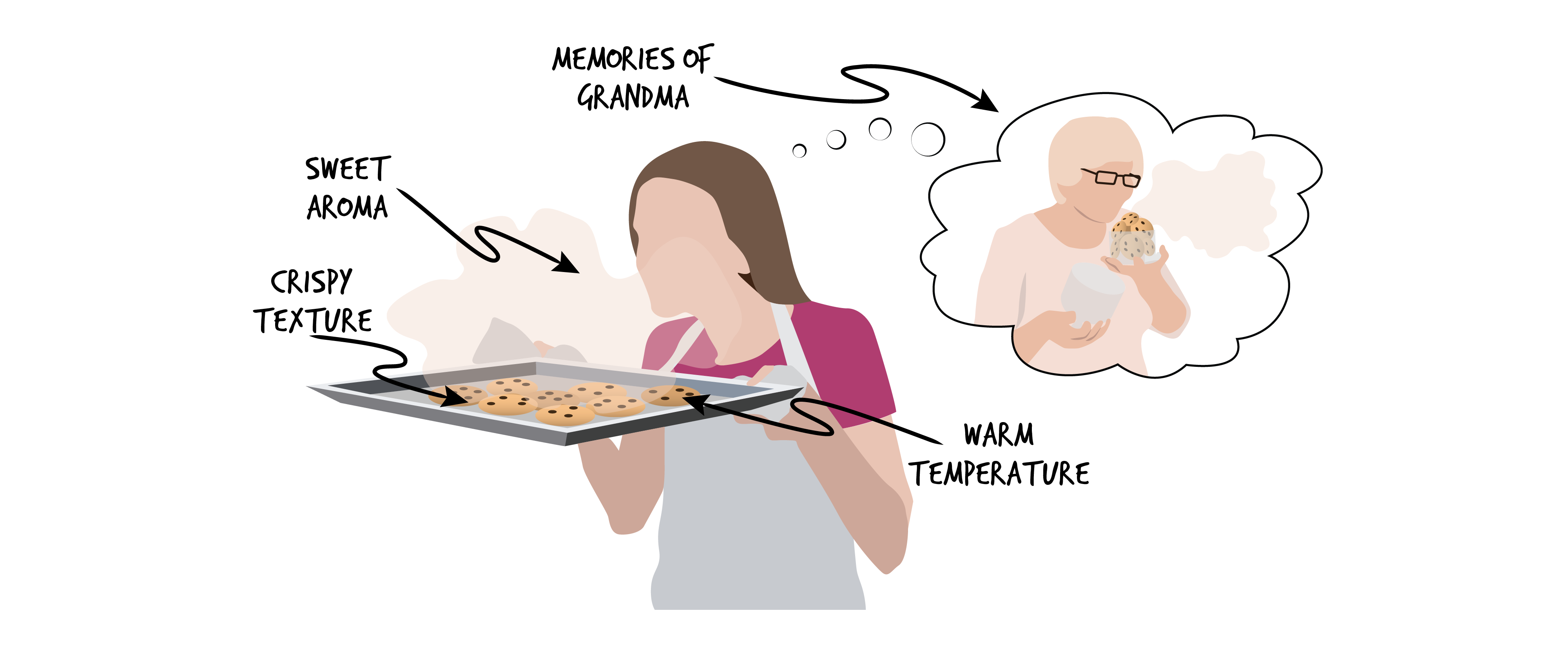

Flavour compositions may also trigger emotional responses since they include tastes, smells, textures, and sounds connected to food that you may have experienced before. They are often associated with pleasant memories of preparing meals and dining with family and friends that are tied to social or cultural rituals. Here we recall Jordan’s (1999) four pleasures: physio-pleasure, psycho-pleasure, ideo-pleasure, and socio-pleasure; each of these pleasures can be part of our eating experiences. For example, the smell of baking cookies may bring up happy, delicious, and emotional childhood memories as in the image below.

Flavour is a Multisensory experience

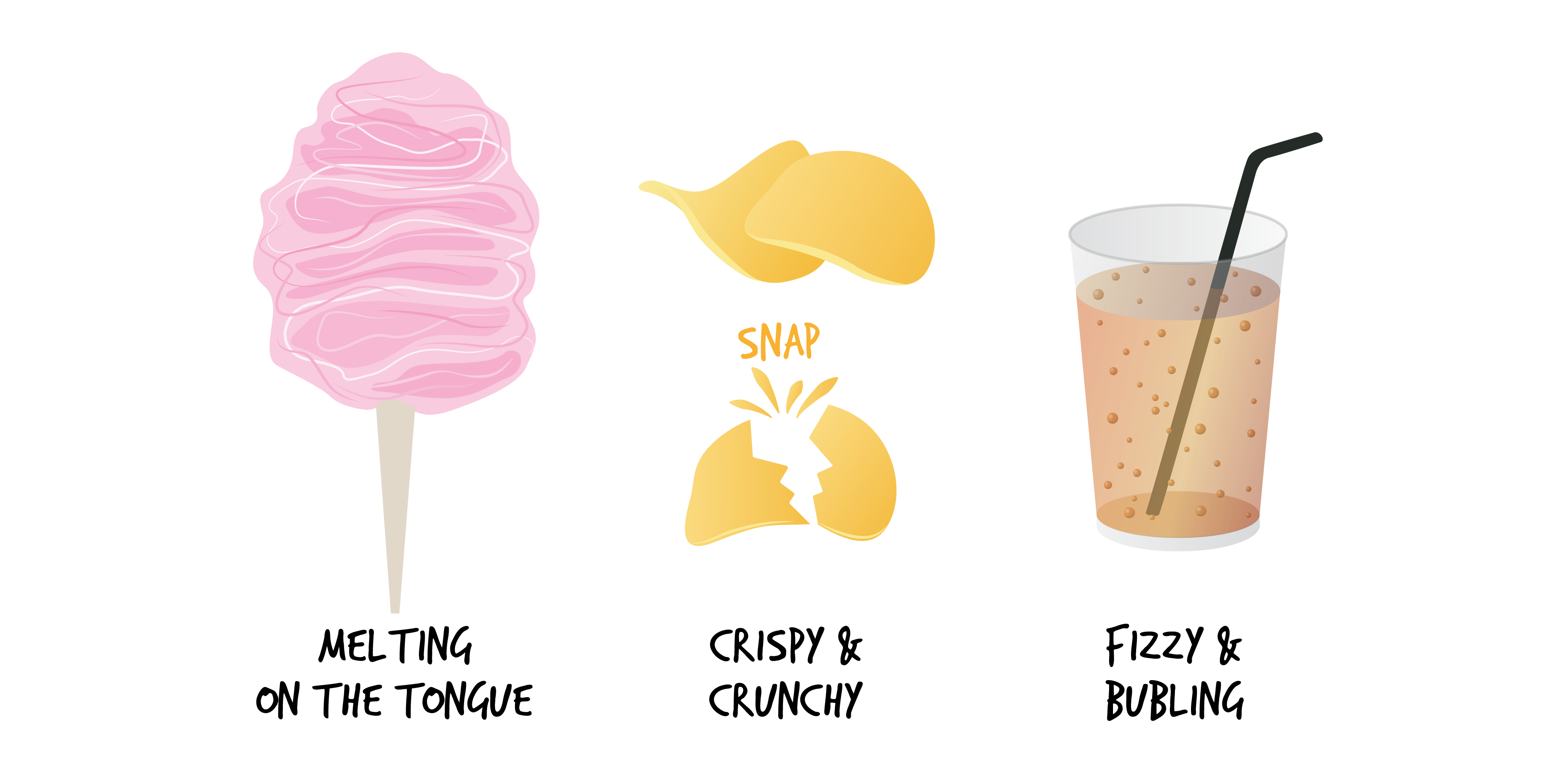

The tastes of food also depend on the contexts in which you experience them – a romantic restaurant, a busy snack bar, or a cold outdoor kiosk on the ice during Ottawa’s Winterlude festivities. Visual cues like colour and composition, along with auditory cues like crunching, fizzing, and cracking also influence your perception of flavours. Researchers have experimented with manipulating the sounds of foods to influence consumers’ ideas about freshness. For example, study participants perceived a louder crunch to imply fresher potato chips (Auvray and Spence, 2008; Lupton 2018). Listen to the sounds of your own chewing; depending on what you eat they could be crackly, crispy, sloshy, or slurpy (Schifferstein et al, 2020).

Flavour compositions are also extremely tactile because the texture of food materials changes while we are chewing; so, the tactile receptors in our mouths respond to and identify the unique physical qualities (texture and temperature) of different types of food. Pay attention to how food feels in your mouth; depending on what you are eating it could feel rough, smooth, sticky, hard, or elastic (Schifferstein et al, 2020). This diverse group of responses is referred to as mouthfeel or the mouth-sense of food (Lupton 2018). You experience mouthfeel when you bite, masticate, and swallow food.

Mouthfeel changes depending on the texture and temperature of different kinds of foods