6.4 Olfactory Design Principles

Instead of applying familiar scents, the car industry was one of the first to deliberately design and associate smells with their luxury brands. Rolls-Royce took the lead in 1965 and other car manufacturers followed in its footsteps (Thompson et al, 2017). From a brand perspective, design and marketing teams consider that scents can be unique product identifiers and try to closely match them to the product or space they are designed for. Thompson et al (2018), offer principles for designing appropriate smells:

Authenticity: Design accurate smells that fit the product or environment, like a chocolate smell in a chocolate retail space or a “clean” scent for hygienic spaces or products. Apple adds olfactory cues to its new products, which have been described as plastic, metal, silicon, printed cardboard, and other scents that seem authentic for electronic products.

Designing Authentic Smells

Intensity: This principle relates to how much a scent is diluted and how strong we perceive it to be, as noted earlier. Ambient scents can be diffused in air conditioning, electronic diffusers, or stand-alone scented products. The goal is to not be too intrusive or powerful and to provide a smell journey that includes “silences and crescendos (similar to the concept of the Piesse scale) in both time and space” (Thompson et al, p. 145).

Designing Ambient Scents

Quality: While toiletries, cleaning and skincare products are the most scented consumer goods, their scents vary due to the formulas for constructing their odours and the quality of ingredients used. As consumers become used to the sophisticated nuances of their personal products, they develop sophisticated smell expectations that designers should be aware of.

Designing products with quality ingredients and materials

Suitability: Since smell perceptions vary based on age, demographics, culture and geographic region, it is important for designers to understand the target users in order to design scents that are suited to their past smell experiences.

Designing scents suitable for target users

Design Applications

The benefits of selecting suitable odours as part of a product’s multi-sensory features include the opportunity to contribute to positive associations in the culture for which the product is intended. For example, we already discussed the practices of wafting smells into retail environments – of baking bread, fresh lemons, and flowery fragrances – to entice us into that environment. In some places, walls can even be studded with smell-emitting pods or fragrances that are diffused to pleasantly manipulate our sensory perceptions.

Not all smell experiences, however, are marketing ploys. Interactions can instigate a smell alert. For example, if you burn rice on the stove or toast in the toaster, the result will be a burnt smell. If it’s extreme your smoke alarm will sound off. It will also sound off if a fire breaks out while you are sleeping and smells are less likely to be processed (this is why smoke detectors are placed near bedrooms) (Lipps 2018). This smell alert may save your life or, at least, keep you safe!

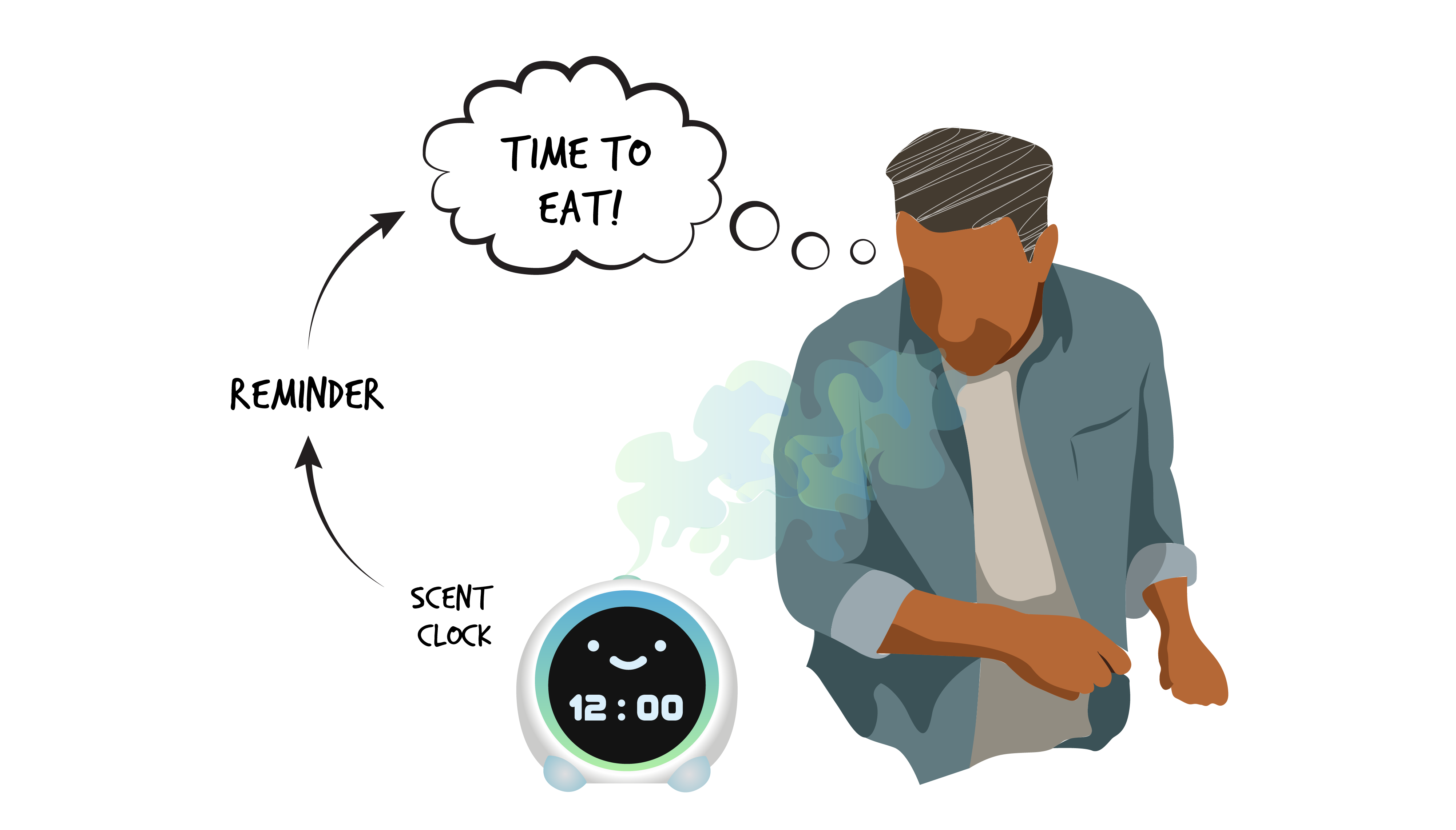

A United Kingdom project that used design to encourage health and well-being in older adults with dementia led to the design of the ODE device, by Rodd Design. It acts like a clock and emits three different food-related fragrances, one for each meal of the day (breakfast, lunch, and dinner), selected from a menu of different odours, to stimulate patients’ appetites by emitting smells they associate with meals (Springwise, 2022; Lipps, 2018; Shepherd, 2006). Jinsop Lee (2013) also describes designs for clocks that emit different smells when activated by the sun at specific times.

Product Scents may be used to remind or alert users to take action: a smell-emitting clock may encourage users to eat at mealtimes (adapted from ODE project, 2022)

Smells may also intentionally be embedded in products as preventative deterrents. For example, a bike lock designed by Skunklock releases a putrid gaseous smell when broken which becomes a crime deterrent, while alerting others to the broken lock (Lipps, 2018). Can you think of an innovative way to use smell in products? How about designing smell alarms into food storage containers to alert you when food stored in them is going bad? In these design concepts, the design team has leveraged the characteristics of smells to change people’s behaviours and avoid a crisis.

Sensory perception involves multiple factors that compete for perceptual attention at once – smell is only one of them! It is wise to become sensitized to your smell experiences – the context of smells related to product use or the environmental odour ambiance – so that it is clear where, when and how many additional scents integrate or compete with one another and other sensory perceptions. As a designer, you may be thinking about why you would choose certain materials, as we discussed in Chapter 4. Imagine if you were to notice that the glossy material you selected for a new water bottle emitted an industrial smell – would you look for a material with a more neutral odour? This is the case with specifying materials in the design of many products for food, from spatulas to containers, to pots and pans. Not only can smell affect the perception of the food product, it can also directly affect the perceived taste experience. Since smell and taste are closely connected, we discuss taste next.