6.3 Categorizing Smells

You can find smells everywhere you go, and in many cases, you may not consciously notice them. As you pay more attention to smells around you, you will also notice that they change as you move into other environments. Each of these scented spaces or places are called smellscapes or scentscapes . Some cities, similar to Peterborough’s oat factory smells mentioned above, have a signature smell (a smell unique to that place or thing). Most places have a combination of smells and as you pay attention to them, you may become more closely attuned to the differences. In researching the nature of urban smells, participants went on guided smell walks in different cities and cityscapes (Guercia, Schifanella, Aiello, & McLean, 2015 and 2016). They were asked to find smells as they walked along and to name them. It turns out that finding smells can be challenging. “Smells are not neatly defined objects; they can travel large distances and appear seemingly unattached from their origin” (Feuer-Cotter, J. 2017). Dr. Kate Maclean (2019) developed a set of activities to help us attune our senses to ways of perceiving and describing smells. By experiencing a smell walk, designers can begin to appreciate the power and importance of smells in a variety of contexts through these three activities:

- Smell catching – breathing deeply to receive smell information.

- Smell hunting – locating the sources of smells closely connected to products or places.

- Smell naming – experimenting with names based on associations with familiar scents).

Become sensitized to smell by taking a smell walk

Given that smells swirl through the environment and dissipate, it is unlikely that the exact same set of smells would be experienced in the same sequence or in the same place repeatedly (Lipps, 2018). Nonetheless, perceptions of places and product interactions are built partially upon smell experiences. Why not take a smell walk to become sensitive to the smells in your neighbourhood?

Activity Time!

Place each of the four items that appear in the column on the right in its appropriate spot along each of the four Smell Spectrum continuums below. First choose the order for the top Smell Spectrum, Synthetic to Natural, then reorder the items appropriately in the next Smell Spectrum, Bold to Faint. Continue reordering for the following two Smell Spectrums, Aromatic to Stinky and Brief to Enduring.

Smell Spectrums

Characteristics of Smells

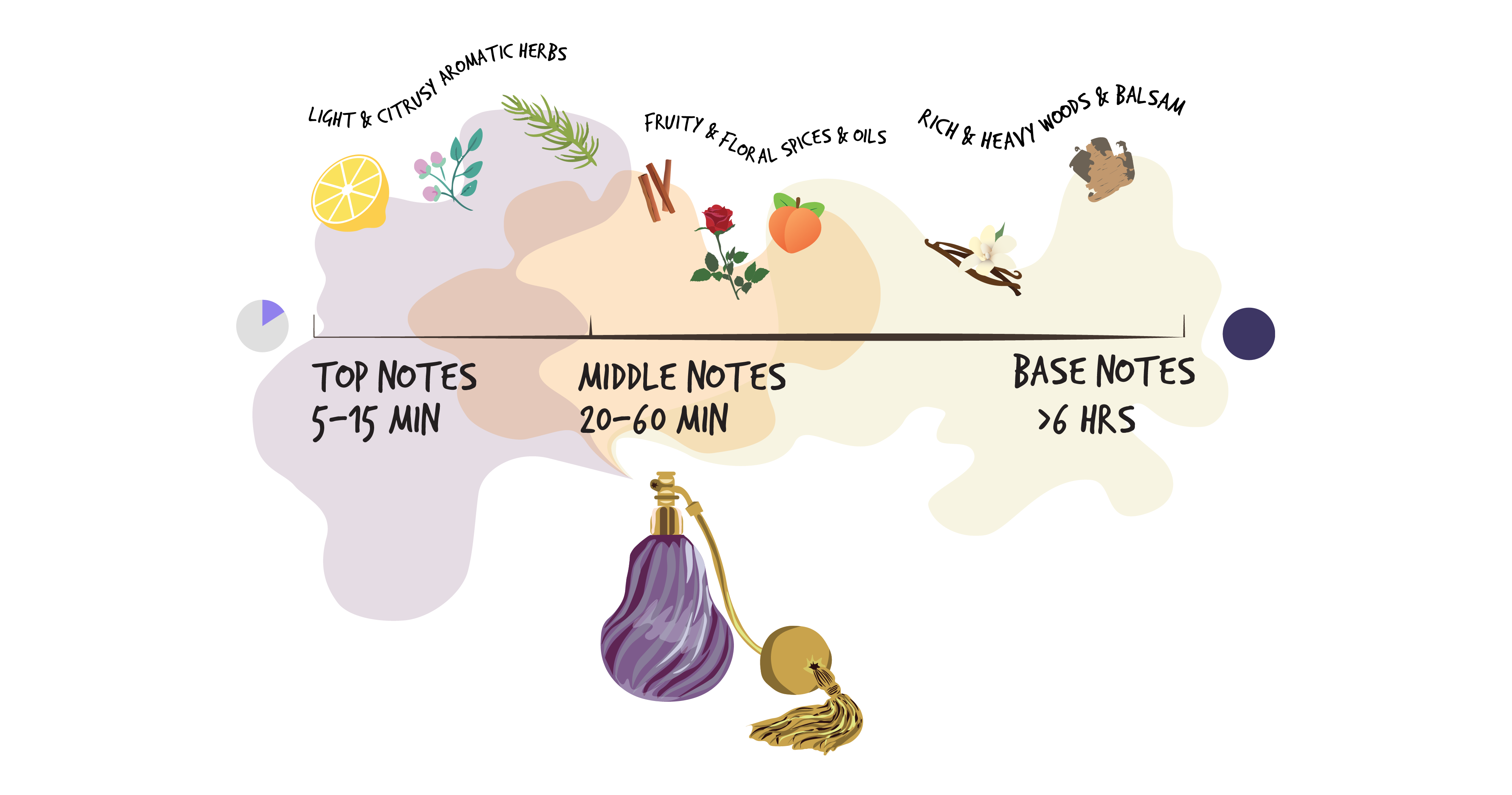

We refer to smells by a number of different names – odours (usually scientific), scents (cosmetic and environmental), and fragrances (cosmetic and alimentary). Let’s consider some significant smell characteristics. Perfumers refer to the notes (or immediate scent you can distinguish) of a smell as top, middle, and base. They may be related to proximity, strength (intensity), or duration of the specific odours, which are terms we will define shortly. They can be combined in layers of different fragrances and active time spans that contribute to a longer-lasting and pleasant experience that we will want to repeat frequently. However, most smells do not last long. “The smell of violets (methyl ionone) is famous among perfumers for persisting for only about half the duration of an inhalation before it becomes imperceptible” (Jasper A., & Wagner, N. 2018, p. 52). This is the result of another common smell phenomenon called olfactory fatigue, in which we experience a rapid loss of perception over the duration of the smell event.

Duration & Layers of different fragrances

For a designer, the ephemeral character of smells means that care and consideration must go beyond the choice of smell. It should also consider the moment when the smell is most intense. Again, when buying a new car, you experience that “new car smell” the moment the door is opened. According to Martin Lindstrom, cars acquire their new car smell via an aerosol sprayed on at the end of the production line. “The smell generally lasts for about six weeks before it’s overtaken by the rough and tumble of dirty running shoes, old magazines, dry cleaning” odours of everyday life (Lindstrom, 2005, p. 15).

These complex considerations may be rather sophisticated for most product design teams, as designing scents is rarely a highly-developed design skill. However, scents are part of many product experiences and the more we are aware of their effect on product interactions, the better. For example, we could consider the scent of salmon, emerging from a tin as we pierce it with a can opener, to be an affordance that provides us with feedback that the opener is working. Or the smell of a toaster in action may send us a different message. It can alert us to how well done our toast is – lightly toasted, darkly toasted, or burnt. For the design team, a well-designed toaster would rarely produce burnt toast and would be adjustable to its users’ personal preferences. It is important to note that smells can also come from the products themselves, such as the materials or electronics, not only from interacting with them. Describing some smells may not be as easy as describing other sensory perceptions like colours, sounds, or shapes.

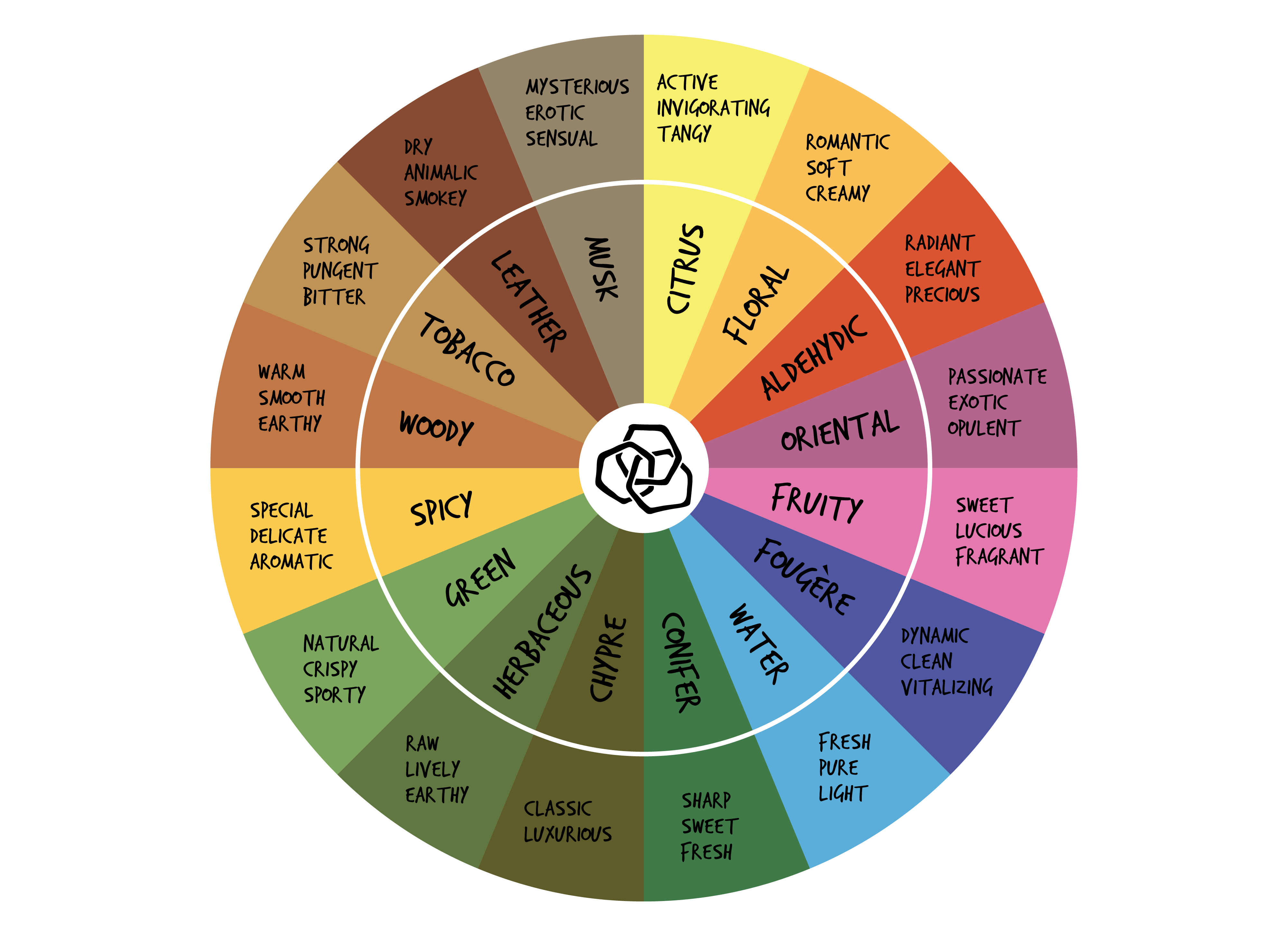

Fragrance Models

Smells can be organized into scent categories and displayed in two-dimensional models similar to colour wheels. One such model is the Drom Fragrance Wheel developed in 1911, in which scents are characterized in relation to specific smells like leather, floral, or herbaceous, and are assigned descriptive adjectives (as discussed in Jasper A., & Wagner, N. 2018).

Drom Fragrance Wheel (adapted from Jasper and Wagner, 2018)

An earlier scent model, developed in 1857, by George William Septimus Piesse, assigned musical chords, harmonies, notes, and progressions to describe melodies and compositions of scents as harmonies or disharmonies (Jasper A., & Wagner, N. 2018; Piesse, 2011). This musical association is a completely different and multisensory way of categorizing and organizing smells and is still used by the perfume industry today!

Piesse’s scale of scent taxonomies: scents are assigned different octaves (Adapted from Piesse, 1857, 2011)

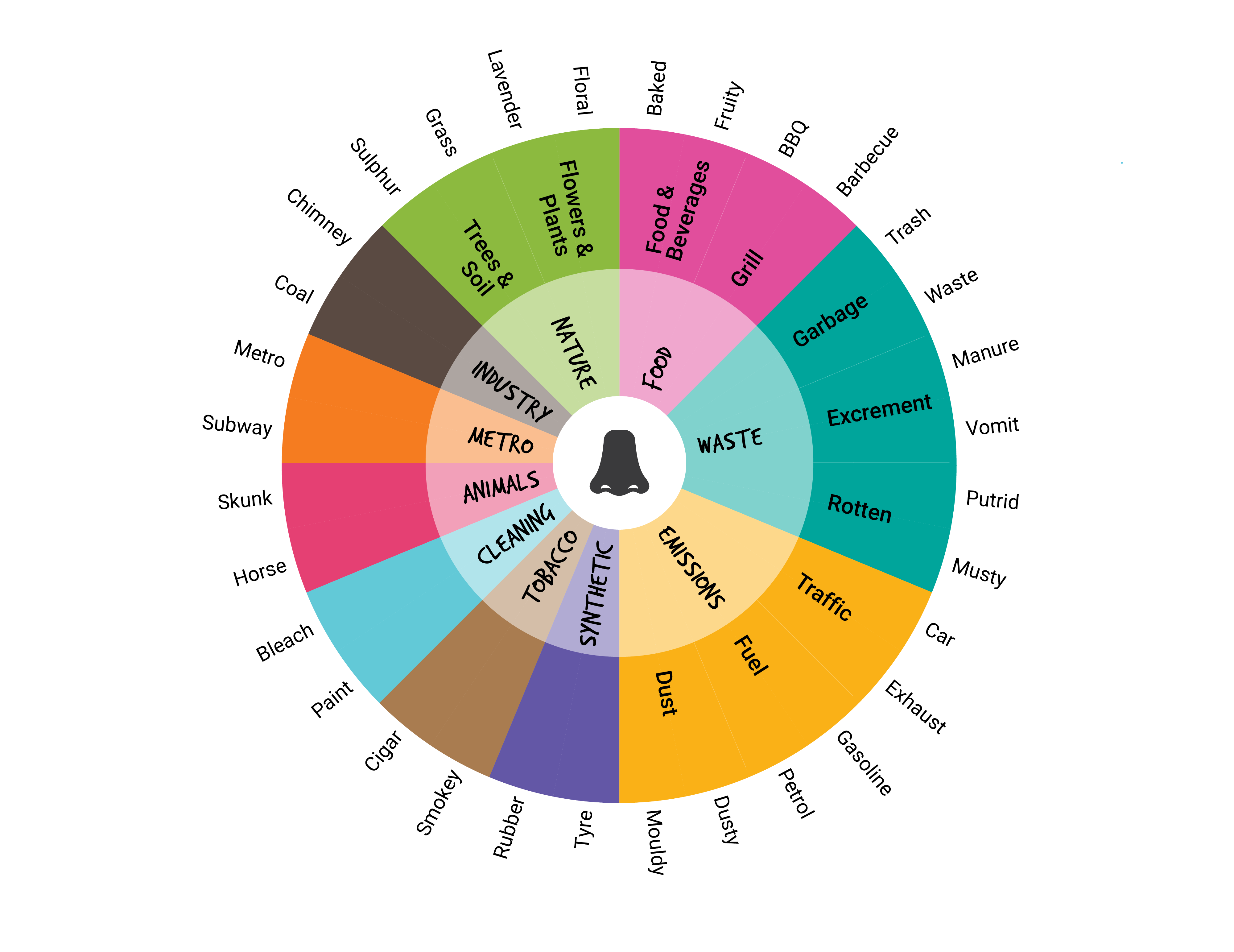

Nonetheless, the models for describing scents are still considered weak and less than ideal representations (Jasper A., & Wagner, N. 2018). In the search for suitable terminology for describing aromas, researchers Guercia, Schifanella, Aiello, and McLean, developed their Urban Smellscape Aroma Wheel to illustrate the ten key smell categories that their smell walk research participants described (2015, 2016). They organized the descriptive words generated by their participants into a hierarchy of urban smells as you can see below. They found that the smell walkers used metaphors related to categories of the smells one finds in the environment. For example, flowers and plants as well as trees and soil fit under the category of “Nature”.

Urban Smellscape Aroma Wheel (adapted from Quercia et al, 2015, 2016)